Was Empress of Iran Farah Pahlavi the Marie Antoinette of her day or a forward-thinking leader unappreciated in her own time?

For some, Empress Farah Pahlavi is a tragic symbol of Iran’s last chance at democracy. For others, she represents the worst excesses of the overthrown shah’s regime in the era before the country’s 1979 revolution.

And for all who know her story, the captivating yet controversial life of Farah Pahlavi remains nothing short of fascinating.

The Early Life Of Farah Diba And A Fateful Introduction To The Shah

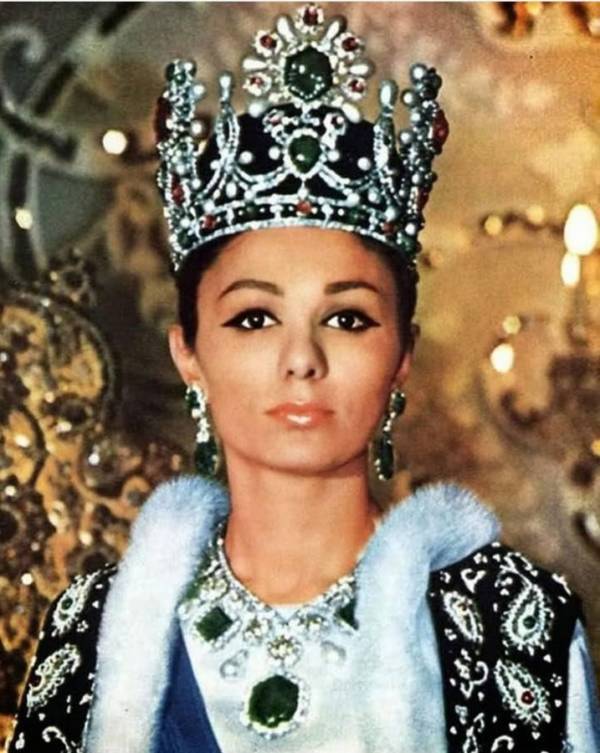

Wikimedia CommonsFarah Pahlavi after her coronation as Empress of Iran.

Farah Pahlavi, née Farah Diba, was born in Tehran in 1938, the only child of Sohrab Diba, an army officer who had graduated from the French military academy of St. Cyr, and his wife Farideh Diba Ghotbi.

The Diba family counted ambassadors and art collectors among its forebears and was placed solidly among Persia’s elite. Farah studied at both Italian and French schools in Iran’s capital and enjoyed a relatively comfortable lifestyle. Her idyllic childhood, however, was marred by the untimely death of her father, with whom Farah was especially close, when she was just eight years old.

Before his death, Sohrab had instilled in his daughter a love of the French language (which was widely spoken in Tehran) and culture. And from her mother, Diba inherited a streak of independence and forward-thinking. Farideh refused to make her daughter wear a veil and, far from selling her off in an arranged marriage, encouraged her to go study architecture in Paris on a scholarship.

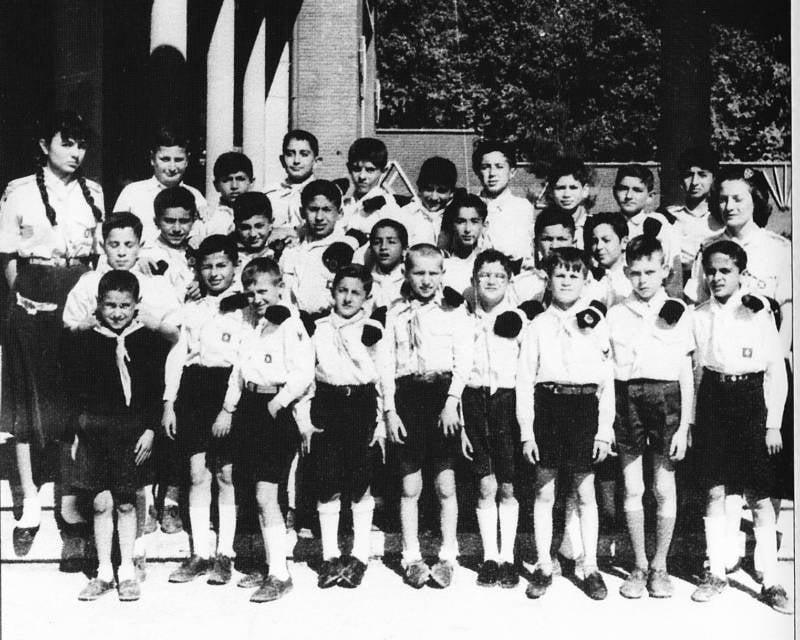

Wikimedia CommonsFarah Diba (far left) with a group of Iranian Boy Scout in Paris in 1955.

Described by her classmates as a “hard worker” who studied well into the night and never cut class, Farah Diba took a rare break from her studies in the spring of 1959 to attend an embassy reception for the ruler (shah) of her country: Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

The gossip among Tehran’s elites claimed that the shah was looking for a new wife after having divorced his second one a year ago due to her inability to bear children. Farah Diba’s name had already been floating around as a potential candidate and the shah would later recall that “I knew as soon as we met… that she was the woman I had been waiting for so long, as well as the queen my country needed.”

Before the year was out, the two were wed.

Farah Pahlavi And The White Revolution

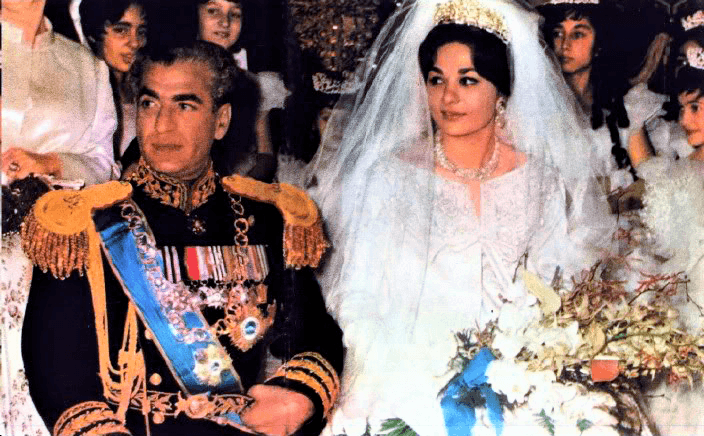

Wikimedia CommonsFarah Diba’s official engagement photo with Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

Mohammed Reza Pahlavi had grand visions for his country. He dreamt of creating a modern Persia which, supported by the country’s tremendous oil wealth, would serve as a haven for democracy and freedom in the Middle East.

In the early 1960s, he initiated his “White Revolution,” a vast plan for social and economic reform that included increased rights for women (including the right to vote), land reform, profit sharing for factory workers, opening shares in government factories to the public, and establishing a “literacy program” to educate the country’s poor.

By the time of the shah’s official coronation in 1967, “Iran enjoyed one of the highest rates of economic growth in the world and a reputation as a bastion of peace and stability in the Persian Gulf.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe Shah and Farah Pahlavi on their wedding day in December 1959.

From the beginning, the shah made it clear to his future bride that her role would not be just ceremonial, as it had for the queens of the past.

Part of Farah Diba’s appeal to the shah, apart from her natural charm and kindness, was the fact that she had been educated in the West and was an independent thinker. Diba was also unique in that her own financial problems and experience as a student gave her an insight into the struggles of the poorer sectors of the country. Diba even declared that as queen, she would devote herself “to the service of the Iranian people.” Together, the royal pair would usher in a “golden age for Iran.”

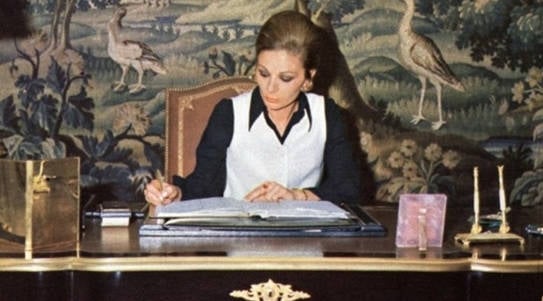

Wikimedia CommonsFarah Pahlavi at work in her Tehran office.

Although Farah Pahlavi had already borne the shah a son and heir by 1960, as a symbol of his total dedication to advancing women’s rights in his country, the shah not only crowned her shabanu (empress) of Iran in 1967, but also appointed her regent. This meant she would rule Iran in the event of his death until their son, Reza II, came of age.

For her part, Farah Pahlavi encouraged her husband’s soft revolution through her support of the arts. Rather than focusing on buying back ancient Iranian artifacts, Pahlavi decided to instead invest in a collection of modern art. It is a testament to her foresight that the collection of Renoirs, Gauguins, Pollocks, Lichtensteins, and Warhols she assembled is worth about 3 billion in today’s dollars.

For her impeccable style, personal charm, and support of the arts, Farah Pahlavi was dubbed the “Jackie Kennedy of the Middle East.”

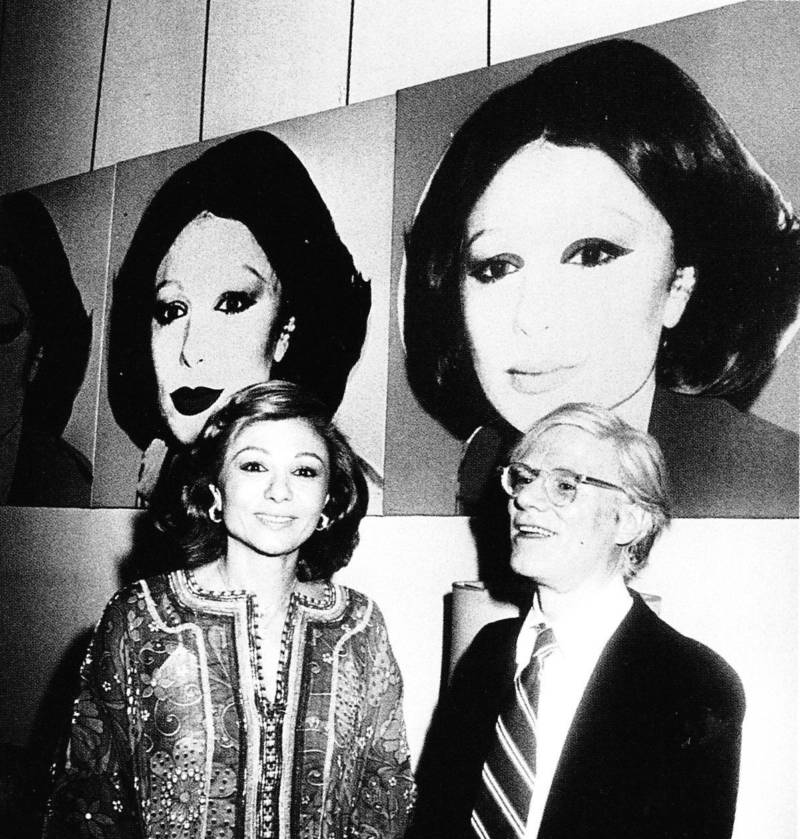

Wikimedia CommonsFarah Pahlavi and Andy Warhol pose in front of the artist’s portrait of the empress at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art.

In 1976, Andy Warhol even traveled to Iran to create one of his famous silkscreen portraits of the empress. Bob Colacello, a member of Warhol’s entourage who accompanied the artist on the trip, later declared that “North Tehran reminded me of Beverly Hills.” Yet just like the Kennedys, the Pahlavi rulers dreams of a Camelot were suddenly and violently shattered. Less than three years after Andy Warhol’s visit, the Iranian capital would be a far cry from Beverly Hills.

The Iranian Revolution And The End Of An Era

Wikimedia CommonsThe shah and shahbanu with the Kennedys in 1962.

Although Iran enjoyed an economic boom thanks to its oil reserves, in the 1970s the country also stood on the front lines of the Cold War.

The same oil that made Iran rich was also an irresistible draw to both Western and Soviet powers, who each tried to exert their influence on the country. The shah and upper classes tended to favor the countries of Western Europe and the United States (particularly after a failed communist-influenced uprising in the 1950s had temporarily forced the shah to flee).

Certain elements of Iranian society, however, were furious with what they saw as the abandonment of their traditional culture and values. They resented the influence of Western culture on Iran’s elites and viewed the shah’s reforms as an attempt to completely root out their heritage.

The Muslim cleric Ruhollah Khomeini was one of the loudest voices calling for the overthrow of the shah. Khomeini had been exiled in 1964 but had been continuing to sow the seeds of discontent in Iran via radio. For all his good intentions, the shah was still a dictator with the power of life or death over his subjects and his brutal suppression of protesters only fueled a cycle of violence in the country.

Wikimedia CommonsAnti-shah protesters deface pictures of Empress Farah Pahlavi.

Things came to a head in September of 1978, when the shah’s soldiers fired into a crowd of protesters, leading to thousands of casualties. The demonstrations quickly turned into riots, with Khomeini consistently fanning the flames.

Finally, in December of 1978, soldiers began to mutiny and the shah’s grip on power was broken. The royal family fled their homeland before finally seeking refuge in the United States in 1979. The shah died in Egypt in 1980 and the still-exiled Farah Pahlavi currently divides her time between the United States and Europe, having never set foot back in Iran.

Wikimedia CommonsFarah Pahlavi in Washington, D.C. in 2016.

The legacy of Farah Pahlavi is a mixed one. Some Iranians fondly recall the reign of the Pahlavis as a Golden Age of freedom and independence. Others view her as a modern Marie Antoinette, spending her country into ruin while the poor continued to suffer.

The empress did leave her country with one very important gift, however. Her billion-dollar art collection is still displayed from time to time, apart from the paintings the current regime deems blasphemous for their depictions of nudity or homosexuality. But while Farah Pahlavi may be gone from her homeland, at least one striking reminder of her time there remains.

After reading about Farah Pahlavi, take a look at some photos of life in Iran before the 1979 revolution. Then, explore an up-close look at the reign of the last shah.