In 1928, Henry Ford broke ground on Fordlândia, a rubber-producing town in Brazil that he hoped would supply his car factories and serve as a model industrial society. Instead, it devolved into a dystopia.

Henry Ford CollectionAerial view of Ford’s rubber town in 1934.

Henry Ford was a man of many contradictions. At once progressive in his treatment of workers and regressive in his racial ideology, this singular man revolutionized the automobile industry and invented the 40-hour workweek — while also railing against the Jews in his newspaper, The Dearborn Independent.

Nothing illustrates Ford’s peculiar blend of forward-thinking conservatism better than his disastrous attempt at creating a rubber empire. In the late 1920s, Ford decided to get into producing his own rubber for Ford Motors and built his vision of a perfect company city in Brazil.

Believing he could impose American customs and assembly-line order on workers from a totally different culture, Ford built a city capable of housing 10,000 that today sits largely abandoned.

Welcome to Fordlândia, one of the 20th century’s most ambitious failed utopias.

The Rise Of Rubber

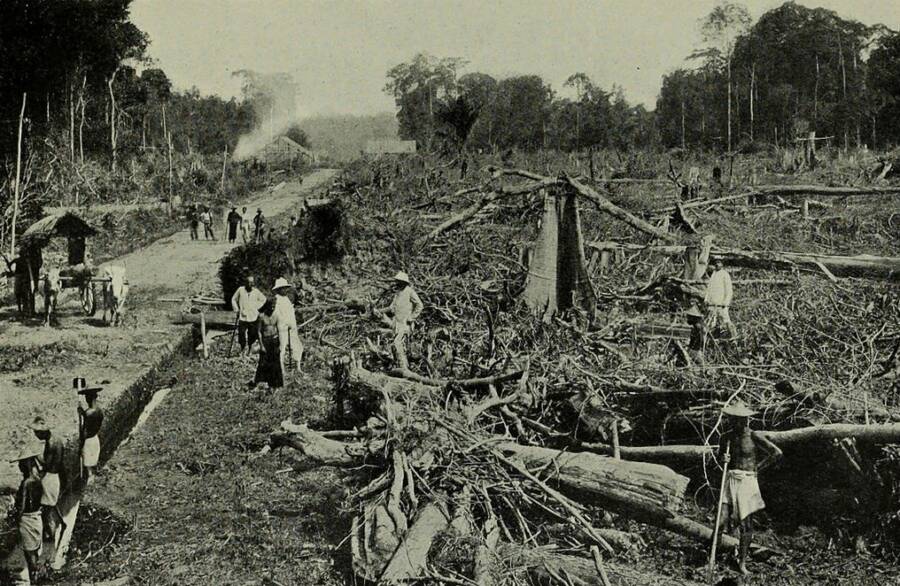

Wikimedia Commons Rubber plantations like this one in Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka) produced huge amounts of the latex needed for tire production.

With the invention of the pneumatic tire and the combustion engine at the end of the 19th century, horseless carriages were, at last, a reality. But for years, the car remained the preserve of the wealthy and the privileged, leaving working and middle-class people to rely on trains, horses, and shoe leather.

That all changed in the 1908, when Ford’s Model T became the first affordable automobile, priced at just $260 ($3,835 in 2020), with 15 million sold in less than twenty years. And each of those cars depended on rubber tires, hoses, and other parts to function.

From about 1879 to 1912, rubber production in the Amazon boomed. However, that changed thanks to the English rubber tapper Henry Wickham who transported rubber seeds to British colonies in India.

Henry Ford CollectionFord’s rubber tree seedling nursery in 1935. Because the trees were planted too close together, the crop suffered from infestations of insects and disease.

Wickham figured the trees could be grown more efficiently there, in the absence of the native fungi and pests that plagued them in Brazil. And he was right. British plantations in Asia were able to grow rubber trees much closer together than was possible in the Amazon, and they soon overthrew Brazil’s rubber monopoly.

By 1922, British colonies produced 75% of the world’s rubber. That year, Britain enacted the Stevenson Plan, limiting the tonnage of rubber exports and raising prices on the increasingly essential commodity.

In 1925, then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover said the inflated rubber prices created by the Stevenson plan “threatened the American way of life.” Thomas Edison, among other American industrialists, attempted to produce inexpensive rubber in America, but he did not succeed.

Against this backdrop, Henry Ford began dreaming of owning his own rubber plantation. Ford hoped to both cut his production costs and demonstrate that his industrial ideals would result in the betterment of workers anywhere in the world.

Ford Sets His Sights On Brazil

Wikimedia CommonsFordlândia would use Hevea brasiliens rubber trees to produce the latex needed for tires, hoses, insulation, gaskets, valves, and hundreds of other items.

In a move that now seems blatantly dystopian, Ford named his rubber town Fordlândia. Ignorant of the difficulties of creating a British-style rubber plantation in the Amazon, Ford reasoned that rubber ought to be grown in its natural homeland, Brazil.

In fact, Brazilian officials had been courting Ford for years to attract his interest to rubber growing. And Ford believed that in Brazil, he could use the land as a kind of blank slate for his vision of the city of the future. “We are not going to South America to make money, but to help develop that wonderful and fertile land,” said Ford.

His utopian aspirations weren’t entirely unfounded. By 1926, the Ford Motor Company was at the forefront of a revolution in transportation, labor, and U.S. society. Apart from his innovation in cars, Ford’s ideas about how to treat his workers were a marvel at the time.

Henry Ford CollectionHenry Ford envisioned Fordlândia as a midwestern town plopped down in the middle of the Amazon, and even had the clocks set to Detroit time.

Employees at his Dearborn plant earned the unusually high wage of $5 a day. Plus, they enjoyed excellent benefits and a healthy social environment in the clubs, libraries, and theaters popping up around Detroit.

Ford was convinced that his ideas about labor and society would work no matter where they were tried. Determined to prove himself right, he turned his sights to securing a rubber empire while creating a utopia in Brazil’s backwoods.

In 1926, Ford sent an expert from the University of Michigan to survey likely sites for a rubber plantation. Eventually, Ford settled on a location on the banks of the Tapajós River in Brazil’s Pará state.

The Founding Of Fordlândia

Wikimedia CommonsFord executives on the deck of the Lake Ormoc, the ship that would carry many of the materials needed for the construction of Fordlândia. Captain Einar Oxholm stands in the middle in the white cap, while Henry Ford stands to his left.

In 1928, the British backed out of the Stevenson Plan, once again leaving rubber prices to the free market. The plan to begin rubber production in the Amazon no longer made financial sense, but Ford carried on with his vision nevertheless.

Ford secured 2.5 million acres of free land, promising to pay 7% of Fordlândia’s profits to the Brazilian government and 2% to local municipalities after 12 years in operation. Though the land was initially free, Ford spent about $2 million on the supplies he would need to build a city from scratch.

Next, he sent two ships to Brazil carrying every last piece of equipment needed to build a rubber-producing town from the ground up, including generators, picks, shovels, clothing, books, medicine, boats, prefabricated buildings, and even a gigantic supply of frozen beef so that his management team wouldn’t have to rely on tropical food.

Henry Ford CollectionFord’s men hired local workers to clear the forest to make way for their new utopian town.

To supervise his new project, Ford appointed Willis Blakeley, an alcoholic exhibitionist who scandalized the inhabitants of the Brazilian city of Belém by walking around his hotel balcony naked and frequently going to bed with his wife in full view of the city’s gentry.

Blakeley was tasked with building a town in the middle of the jungle, complete with white picket fences and paved roads, with clocks set to Detroit time and Prohibition enforced. But as effective as he might have been in Michigan, he had no idea how to manage a jungle outpost and knew nothing about rubber.

Blakeley finally broke ground on Fordlândia before his incompetence grew to be too much for Ford, and he was replaced later in 1928 with the Norwegian sea captain Einar Oxholm. Oxholm wasn’t much better, and he was in no way qualified to manage the rubber trees, which had had to be imported from Asia after local growers refused to sell seeds to Ford.

What’s more, the ignorant Blakeley had planted the trees too close together, encouraging huge populations of parasites and pests to infest the crops and ruin the rubber.

Fordlândia’s Workers Revolt

Henry Ford CollectionFord’s workers lived in a neighborhood of American-style homes where Prohibition was enforced.

The 3,000 local employees of the Companhia Ford Industrial do Brasil had come to work for the eccentric industrialist expecting to be paid the $5 their northern counterparts enjoyed, and thinking they would be able to live their lives much as they had before.

Instead, they were dismayed to learn that they would receive $0.35 per day. They were forced to live on company property in American-style homes built on the ground, instead of in their traditional dwellings which were elevated to keep tropical insects out.

Workers were also forced to wear American-style clothing and nametags, had to eat unfamiliar foods like oatmeal and canned peaches, were denied alcohol, and were strictly forbidden to associate with women. For entertainment, Ford pushed square-dancing, poetry by Emerson and Longfellow, and gardening.

On top of that, the workers, used to the slower pace of rural Brazil, resented being subjected to shift whistles, timesheets, and strict orders for efficient movement of their own bodies.

Henry Ford CollectionThe Brazilian workers staged a revolt against Ford’s men in 1930.

Finally, in December 1930, John Rogge, Oxholm’s successor as manager, began to dock the workers’ pay to cover the expense of their meals. He also fired the waiters who had previously brought workers their food, ordering them to use industrialized cafeteria lines instead. Ford’s Brazilian employees had had enough.

Exploding in fury at the demanding and condescending treatment, Fordlândia’s workforce launched into a full-scale revolt, cutting the telephone lines, chasing away the management, and only dispersing when the army intervened.

But reality was only beginning to decimate Ford’s dream of creating an industrialized society in Brazil.

The End of Fordlândia

Henry Ford CollectionDespite sinking $20 million into Fordlândia, Ford was never able to produce a significant amount of rubber in Brazil.

In 1933, the Ford Company’s management shifted most of its rubber production 80 miles downriver to Belterra, where factional rivalries within the company continued to hinder productivity as the effort struggled on.

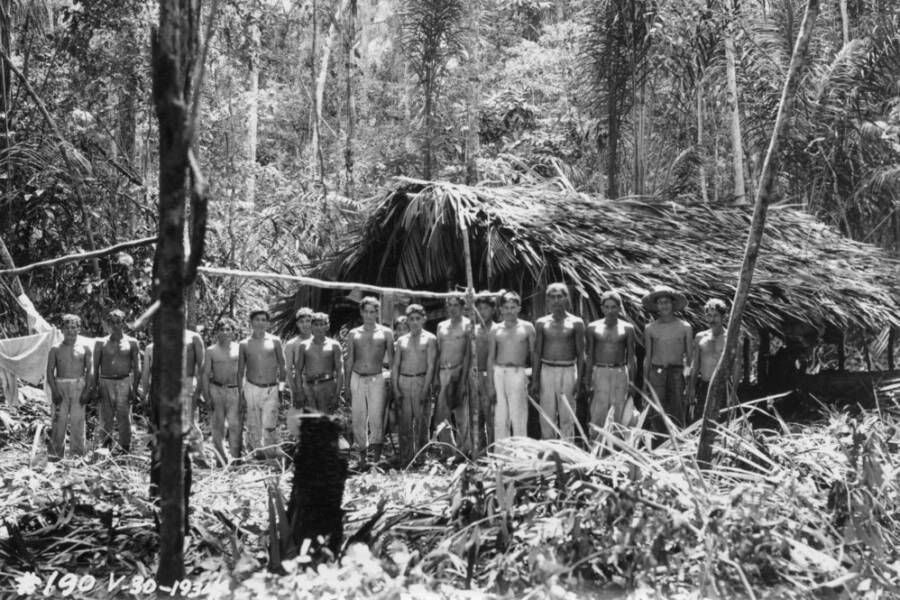

By 1940, only 500 employees remained at Fordlândia, while 2,500 worked at the new site in Belterra. Employees at Belterra weren’t subjected to the same restrictions as the first Fordlândia workers and happily kept to more traditional Brazilian customs, food, and working hours.

Only in 1942 would the commercial tapping of rubber trees in Belterra begin. Ford produced 750 tons of latex that year, falling far short of the 38,000 tons he required annually.

During World War II, rubber production in British colonies stalled. Unfortunately for Ford, a leaf disease epidemic in his rubber plantations hurt his production numbers as well.

Wikimedia CommonsFordlândia’s main warehouse as it appears today. After the departure of Ford executives, the city was gradually absorbed into the city of Aveiro, where it’s now home to about 2,000 inhabitants.

In 1945, Ford sold both his rubber plantations back to Brazil for just $250,000, although by this point he had spent about $20 million on the project. A Brazilian company called Latex Pastore continues to produce latex at Belterra, but Fordlândia remains largely abandoned. Neither site ever produced a significant amount of rubber under Ford.

The American-style town that Henry Ford dreamed would house 10,000 workers is now home to about 2,000 people, many of them squatters. The blank slate Ford imagined he would find in Brazil turned out to be inhabited by people with a robust culture of their own who chafed under the midwestern customs and rules imposed on them.

Ford’s failed experiment later served as a model for modern dystopian tales. For example, writer Aldous Huxley based the setting for his highly influential novel Brave New World on Fordlândia. Characters in the novel even celebrate Ford Day and number the years according to the Anno Ford calendar.

Though in his time, Henry Ford was regarded as a visionary, his legacy now rests largely in desolation. As one resident of Fordlândia observed in 2017, “It turns out Detroit isn’t the only place where Ford produced ruins.”

Next, have a look at tragic images of abandoned buildings in Detroit after the decline of the city’s automobile industry. Then learn more about Henry Ford’s dark fascination with scientific racism and Nazism.