Much has been said and written about Steve McQueen’s “12 Years a Slave,” the film adaption of an 1853 autobiography by Solomon Northup, a free black man who was kidnapped in Washington, D.C. and sold into slavery in 1841. A realistic depiction of the brutality of slavery, the film has been hailed as long overdue, especially because it’s based on a memoir that McQueen said kept him wondering why he had never heard of it before.

160 years later, Northup’s story is now reaching its largest audience ever. The buzz surrounding the movie could make it an Oscar winner when the awards are handed out in March.

Meanwhile, Northup belatedly enters the pantheon of most influential slaves in American history. Here are a few others whose stories have left an indelible mark on the fabric on our country.

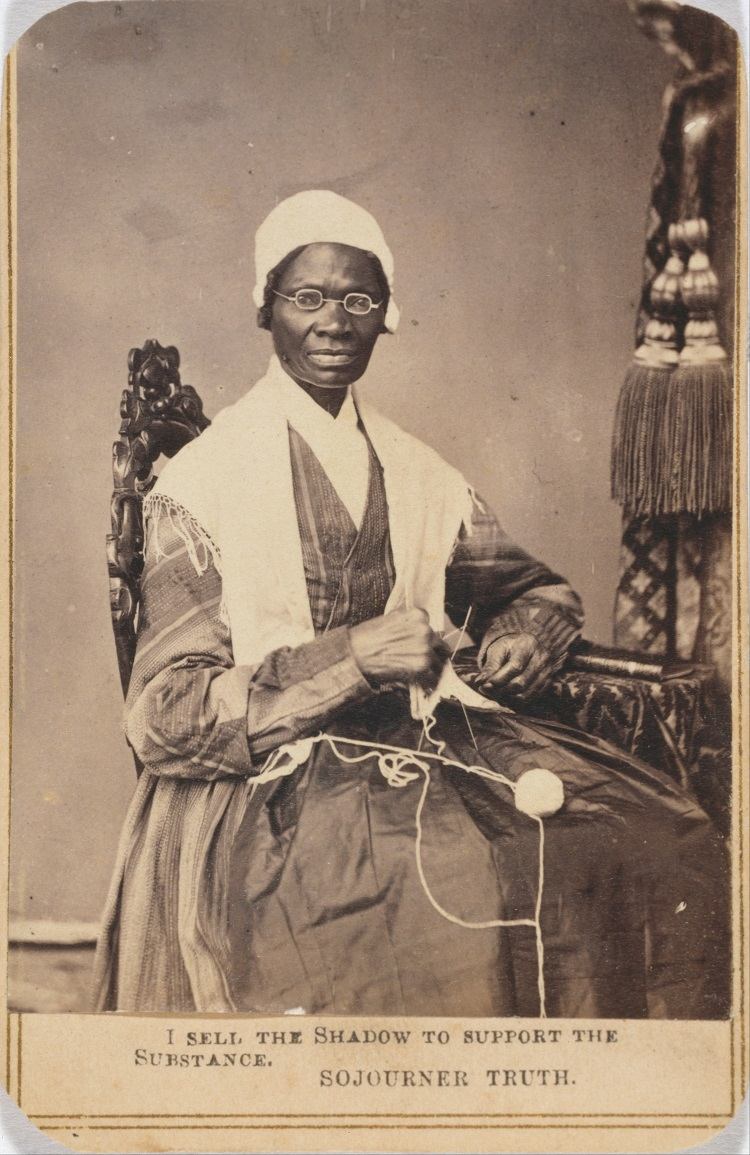

Former Slaves: Sojourner Truth

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Sojourner Truth was one of the most noteworthy activists of her time. A black woman who fought on behalf of abolition of slavery and women’s rights, she almost certainly faced more hardship and opposition than other people of her race or gender. But at 6-feet, 2-inches tall and reputedly stronger than most men at that time, she was a formidable force. Bought and sold four times as a slave, Truth carved her own path in 1843 when she changed her name from Isabella Baumfree and set off East.

Said Truth to her friends regarding her name and travels, “The Spirit calls me [East], and I must go…the Lord gave me Truth, because I was to declare the truth to the people.” Eventually, Sojourner Truth became a contemporary of men such as Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison when she joined the abolitionist group the Northhampton Association of Education and Industry in Massachusetts.

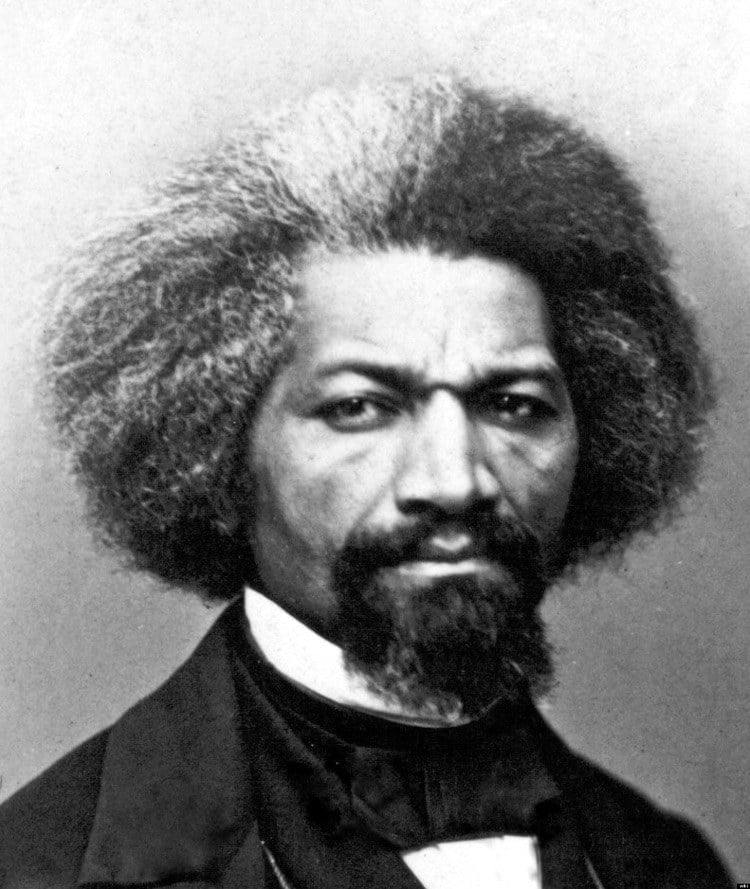

Frederick Douglass

Source: The Huffington Post

The man history would remember as Frederick Douglass was born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey in 1818, but chose his own name after a character in Sir Walter Scott’s book “The Lady of the Lake.” Born a slave, Douglass escaped Maryland in 1838 and eventually settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he would become one of the most influential men of his time. Douglass conferred with President Lincoln and offered his personal thoughts about emancipation of the slaves, both in spoken word and in his 1848-founded abolitionist newspaper, The North Star. Like many influential former slaves, Douglass was biracial and never knew his white father.

His mother was a slave and two of his sons, Charles and Lewis Douglass, enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts, the first all-black infantry division, memorialized in the 1989 film “Glory.”

In addition to his work on behalf of abolition, Douglass was an early supporter of women’s issues and lectured about human rights into his old age. He was nominated for vice president of the United States as a member of the Equal Rights Party in 1872. Last summer, Speaker John Boehner unveiled a statue of Douglass in the U.S. Capitol, where it joins those of just two other African-Americans enshrined in Emancipation Hall: Martin Luther King, Jr. and Sojourner Truth.

Influential Former Slaves: Elizabeth Keckley

Source: Virginia is for Lovers

Before the term First Lady came into use, Mary Todd Lincoln preferred to be called Mrs. President and she insisted on dressing the part. It makes sense that one of her closest friends during her husband’s presidency would be Elizabeth “Lizzy” Keckley (also spelled Keckly in some writings), a former slave who would become personal dressmaker to Mrs. President.

Keckley, whose father was also her master, was a remarkable woman born into slavery and served as a domestic in her father’s household before moving on to the homes of other relatives when she was given as a “gift.” Using her exceptional skills as a seamstress, she purchased freedom for her herself and her son, eventually opening a shop in Washington, D.C. and becoming a businesswoman. There, she caught the attention of Mrs. Lincoln, who was well-known for her ostentatious wardrobe.

Source: NPR

Keckley became part of the Lincolns’ inner circle, often combing President Lincoln’s hair, for which she received his comb and brush from Mary Lincoln after his assassination. Keckley eventually penned a memoir on these events called “Behind the Scenes”. It shouldn’t come as much surprise that the mercurial Mary Lincoln saw Keckley’s work as a betrayal of their friendship and never spoke to her confidant again.

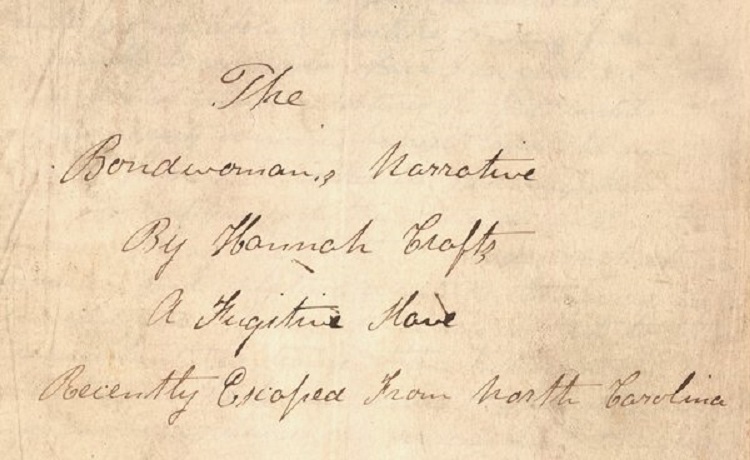

Hannah Bond

Like that of Solomon Northup, Hannah Bond’s influence has gained traction well over a hundred years following her death. If South Carolina English professor, Gregg Hecimovich of Winthrop University, is correct in his deductions, Bond is the author of a 150-year-old manuscript whose scribe remained a mystery for many years.

What was assumed to be a semi-autobiographical account of a Southern house slave named Hannah Crafts, “The Bondwoman’s Narrative” is verified to have been written sometime between 1853 and 1861. A clothbound manuscript of the unpublished book languished in a New Jersey attic until a scholar bought it some 100 years later from a bookseller in New York.

In 2001, it captured the attention of African-American history scholar and literary critic Henry Louis Gates, who bought it without ever being able to ascertain the true identity of its author. It was published in 2002, becoming a best seller. The mystery of the author was solved just last summer when Hecimovich identified the writer as Bond, whose life was very similar to the manuscript’s protagonist. She escaped slavery by disguising herself as a boy and eventually lived in upstate New York with the Crafts family, which explains the pseudonym. Other experts have now confirmed Hecimovich’s findings.

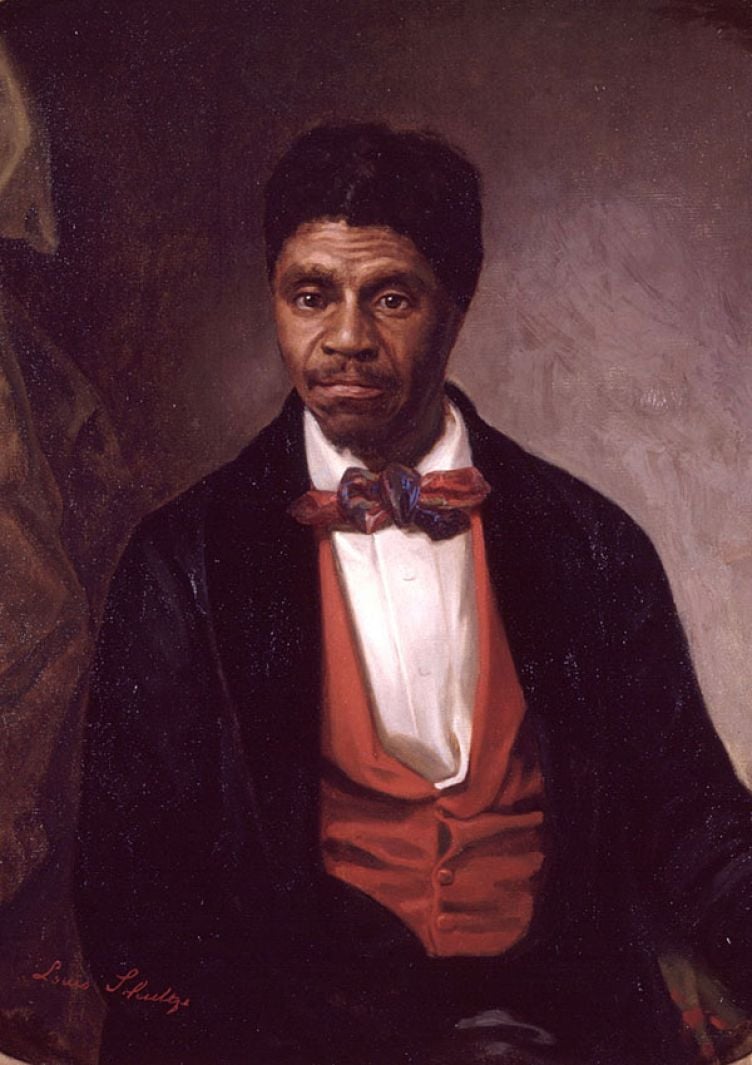

Influential Former Slaves: Dred Scott

Certainly one of the most courageous slaves of the 19th century, Dred Scott ultimately sought his freedom by fighting for it through the tangles of the U.S. judicial system. Having failed to purchase freedom for himself and his family, Scott first filed legal suit in St. Louis Circuit Court in 1846. The logic was that even though they were slaves, Scott and his family had lived with their master in states and territories where slavery was illegal, and should therefore be given freedom.

After a protracted series of retrials and appeals, the Dred Scott v. Sandford case went before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1857. The court decided 7-2 against Scott, citing that African Americans were not US citizens and therefore had no standing to sue within the federal court system. He was eventually returned to the first family that had owned him, and all four Scotts were freed by their owner less than three months after the Supreme Court ruling.

Scott had precious little time to enjoy his freedom he spent more than a decade fighting for: he died in 1858 from tuberculosis. Nevertheless, his legacy lives on within the very document that failed to grant him his freedom. Following the Civil War, the Reconstruction Amendments made up for the dreadful Scott decision and functionally superseded the abominable words of the Taney Court.