From age 16 to 21, Frank Abagnale Jr. impersonated a pilot, posed as a lawyer, and cashed 17,000 fake checks — at least according to Catch Me If You Can.

PictureLux/The Hollywood Archive/Alamy Stock Photo Leonardo DiCaprio, who played Frank Abagnale Jr. in the film Catch Me If You Can, next to the real Abagnale.

“I was always aware that I was Frank Abagnale Jr., that I was a check swindler and a faker, and if and when I were caught I wasn’t going to win any Oscars. I was going to jail.”

By his own admission, Frank Abagnale Jr. was a con man. In his memoir Catch Me If You Can, Abagnale describes a life of petty crime at a young age that eventually led to higher-risk cons. His most infamous stunt was impersonating a Pan American World Airways pilot, though he also claimed to have developed innovative methods of forging checks, supposedly enabling him to net himself $2.5 million from various schemes.

This all reportedly came to an end after he was caught in 1969 and eventually sentenced to 12 years behind bars. But a few years into his sentence, he said that he was pulled out of prison to help the FBI catch like-minded fraudsters. By 1980, Abagnale had published the semi-autobiographical book Catch Me If You Can. The successful memoir was later adapted into a hit 2002 movie by the same name, directed by Steven Spielberg and starring Leonardo DiCaprio as Abagnale.

“I’ve been described by authorities and news reporters as one of this century’s cleverest bum-check passers, flimflam artists and crooks, a con man of Academy Award caliber,” Abagnale wrote of himself in Catch Me If You Can. “I was a swindler and poseur of astonishing ability.”

If everything Abagnale wrote about his life is true, then this statement is hard to dispute. But over the years, some critics have cast doubt on his story — with one even alleging that he made most of it up.

So who is Frank Abagnale Jr.? What did he do during his infamous crime spree? And how much of Catch Me If You Can was real?

Frank Abagnale Jr.’s Early Life, According To Frank Abagnale Jr.

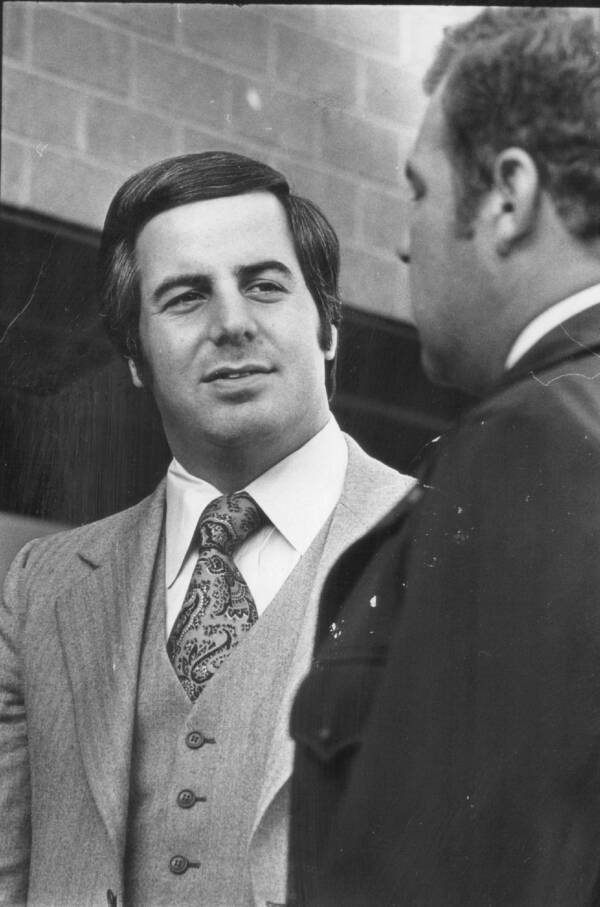

Kenn Bisio/The Denver Post/Getty ImagesFrank Abagnale Jr. in 1978.

Frank William Abagnale Jr. was born on April 27, 1948 in Bronxville, New York. He was one of four children born to Frank Abagnale Sr., a stationery business owner with a penchant for politics, and Paulette Abagnale.

The marriage didn’t last, and Frank Jr. was just 12 years old when his parents separated. Their divorce was finalized a few years later.

“The situation did have its effect on us boys, of course,” Frank Jr. recalled. “Me in particular. I loved my dad. I was the closest to him, and he commenced to use me in his campaign to win back Mom.”

According to his memoir, it was during this period that Frank Jr. scammed his first victim: his father. When he was 15, his father gave him a gasoline credit card. Frank Jr. used the card to pay for auto parts, which he returned for cash. He claimed to have run up a bill of $3,400 in three months.

He also committed petty crimes like shoplifting, eventually leading to more serious crimes like car theft and impersonating a police officer.

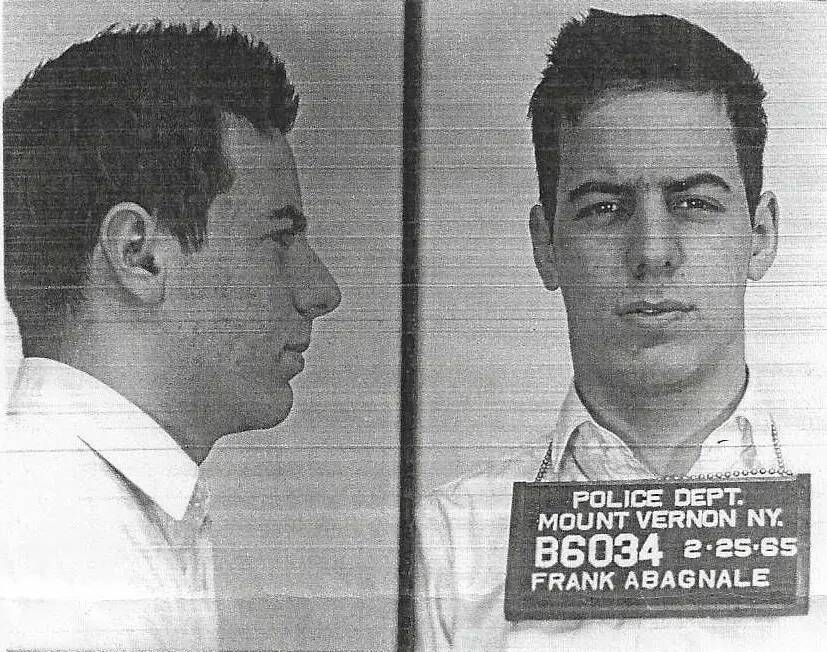

Mount Vernon Police DepartmentFrank Abagnale Jr.’s booking photo from 1965.

At one point, Abagnale said that he was sent to a “private school for problem boys in Port Chester, New York.” He also claimed to have attended Iona Preparatory School in New Rochelle, New York until he was 16. But science journalist and author Alan C. Logan, who investigated Abagnale in the 2020 book The Greatest Hoax on Earth: Catching Truth, While We Can, says there is no evidence in the school’s yearbooks or from alumni to confirm this.

But while potentially lying about his high school education is a minor detail in the grand scheme of things, it could raise questions about other aspects of Frank Abagnale Jr.’s story — including his most infamous scheme.

Impersonating A Pan Am Airline Pilot

The most infamous chapter of Frank Abagnale Jr.’s life started when he was just 16 or 17. He obtained a Pan American World Airways pilot uniform and created a fake airline ID. By that point, he had been told that he looked older than his real age, which likely made his impersonation more believable.

In 1965, he made a big show out of informing Mount Vernon news outlets that he had graduated from a piloting academy — only to be arrested for forging checks shortly thereafter. But his ongoing legal troubles did little to change his mind about the whole “pretending to be a pilot” scheme.

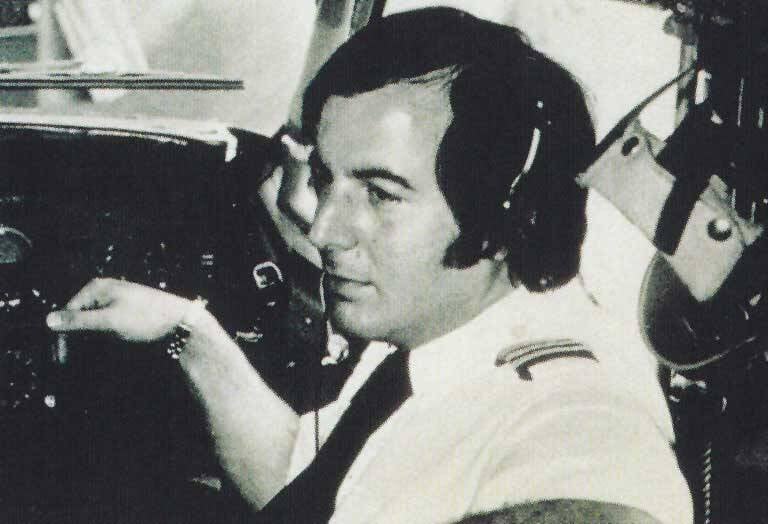

Frank Abagnale Jr.A rare photo of Frank Abagnale Jr. in the cockpit of an airplane.

Obviously, Abagnale couldn’t fly a plane — and fortunately, for his scheme to work, he didn’t have to. It all came down to two things: the uniform, and the airline industry’s “deadheading” system, a practice where off-duty pilots and crew members are given free rides to reposition them for upcoming flights.

As Abagnale recalled, “There is enchantment in a uniform, especially one that marks the wearer as a person of rare skills, courage, or achievement.”

He presented himself as a Pan Am pilot needing to travel for work, allowing him to hitch rides in the jump seats of various airplanes. This not only granted him free transportation, but also access to hotels and other amenities that were specifically reserved for airline staff.

Supposedly, Abagnale visited over 80 countries during this scheme, all without ever operating an aircraft (though he did flip on the autopilot when asked to take control). That is, of course, according to his own account.

Alan C. Logan, on the other hand, claimed that after he examined public records and old newspaper articles and interviewed people who spoke about their encounters with Abagnale, a different story played out.

Paula Parks CampbellPaula Parks Campbell, a flight attendant who said Frank Abagnale charmed her family before stealing from them.

“What really happened was that, dressed as a TWA [Trans World Airlines] pilot, which he only did for a few weeks, [Abagnale] befriended a flight attendant called Paula Parks,” Alan C. Logan stated. “He followed her all over the Eastern Seaboard, identified her work schedule through deceptive means, and essentially stalked the woman.”

Speaking to the New York Post, Paula Parks Campbell recalled that when Abagnale met her family in Baton Rouge, they “fell in love with him,” despite her feeling uneasy that he seemed to be following her from airport to airport. She also said that Abagnale stayed with her family for six weeks while supposedly on furlough and then stole $1,200 from her family before leaving.

“He said he never hurt little people, just went after big businesses,” she said. “That’s the one that sticks in my craw. My mama’s heart was broken.”

Check Fraud, Close Calls, And A Famous Arrest

Flying for free and receiving airline-funded accommodations were certainly valuable perks of the con, but they didn’t exactly earn Frank Abagnale Jr. a paycheck. After all, he wasn’t actually an employee of Pan Am, or any airline for that matter. So he had to come up with some other way to make money.

“It’s a scientific fact that the bumblebee can’t fly, either. But he does, and makes a lot of honey on the side,” Abagnale later wrote. “And that’s all I intended to be. A bumblebee in Pan Am’s honey hive.”

Paula Parks CampbellFrank Abagnale Jr. in his pilot’s uniform.

Posing as a pilot did, at least, make him seem more credible when he approached banks and businesses with fraudulent checks. He claimed that he cashed about 17,000 bogus checks totaling $2.5 million.

That said, his con wasn’t airtight, and he had several close calls. Sometimes, he said, he would opt for different disguises, impersonating a lawyer, a sociology professor, and a doctor at various points in time.

“I made a lot of exits through side doors, down fire escapes or over rooftops,” he later reflected on his crime spree. “I abandoned more wardrobes in the course of five years than most men acquire in a lifetime. I was slipperier than a buttered escargot.”

His luck seemed to run out, however, in 1969, when he was arrested in Montpellier, France. By that point, he was wanted for a number of crimes in both France and Sweden, including fraud and theft.

DreamWorks PicturesChristopher Walken and Leonardo DiCaprio in Catch Me If You Can. (Walken played Frank Abagnale Sr.)

By the time he was 21, Abagnale says, his capture had brought his schemes to an end. But of course, his story didn’t end there.

Abagnale served time in both France and Sweden before being deported to the United States, where he was sentenced, in 1971, to 12 years in a federal penitentiary for fraud. But Abagnale said the government eventually pulled him out of prison before his sentence was over — to work for the FBI.

Today, Abagnale claims to have had a relationship with the FBI for more than 40 years. “There is no evidence to support this claim,” asserts Logan. Meanwhile, the FBI itself has no comment on the matter.

How Much Truth Is There To Frank Abagnale Jr.’s Story — And Catch Me If You Can?

DreamWorks/Amblin film/Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy Stock PhotoFrank Abagnale Jr. has said that Catch Me If You Can was about “80 percent accurate,” but some critics have raised serious doubts about this claim.

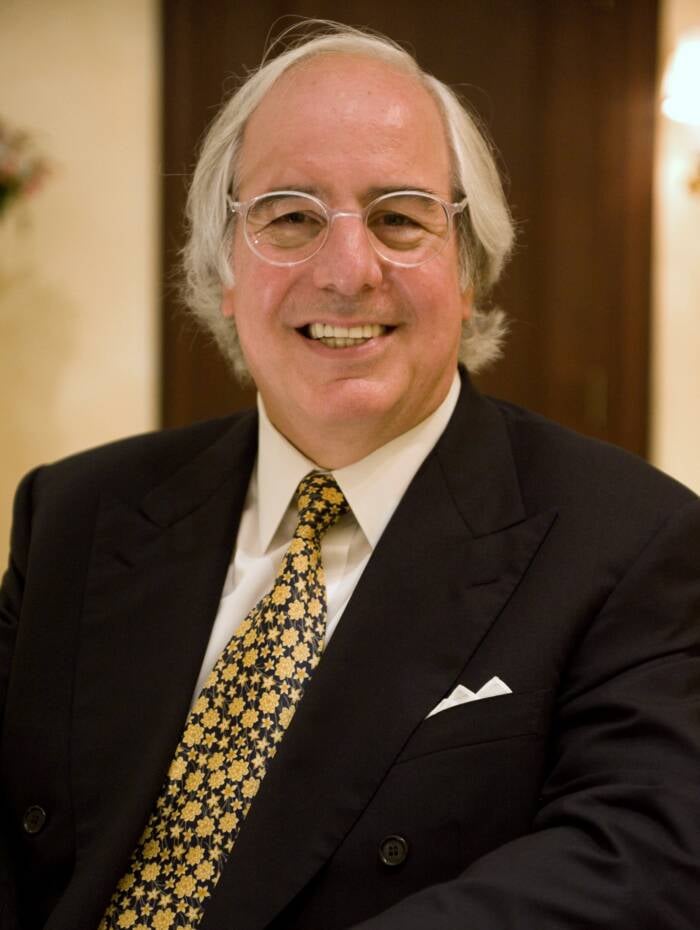

There is at least some information about Frank Abagnale Jr. since his 1969 arrest that can easily be confirmed. In 1976, he founded a security consulting firm called Abagnale & Associates, which focuses on topics like fraud prevention and secure documents. He’s also authored books on fraud prevention, such as The Art of the Steal and Stealing Your Life.

While the FBI has never made an official statement about what Abagnale has or hasn’t done for them, he has given some lectures at the academy.

But what about the most exciting chapter of Abagnale’s story — outlined in his book Catch Me If You Can and later dramatized in a Steven Spielberg movie? According to Abagnale himself, the movie was about “80 percent accurate,” with most of the changes having to do with his family life and the specific ways he avoided capture by the authorities. But others have said that the movie was far more based in fantasy than reality.

Though it wasn’t as widely reported decades ago, Abagnale has faced some skepticism about his story ever since he first published his book in 1980. A journalist asked him in 1982 whether he had engaged in deception, to which Abagnale said that if he had, “Well, then, I am the world’s greatest con man. As one gentleman said to me, ‘If you didn’t do all those things, and you’ve made all this money you’ve made in advances, royalties, and speaking engagements, then you are in fact the world’s greatest con man.'”

Of course, the Spielberg film put a much bigger spotlight on his life story, which also opened his narrative up to more scrutiny, especially in the internet age. That said, the most prominent criticisms have come in recent years, with Alan C. Logan being the best known thanks to his 2020 book.

Wikimedia CommonsWhen asked about Alan Logan’s book and the allegations that Logan made, Frank Abagnale Jr. said, “I have not read the book, nor do I think it is worthy of a comment.”

While it’s clear that Abagnale did impersonate a pilot, did forge checks, and was captured by authorities in Europe, Logan says that Abagnale was behind bars for much of the time that he claimed to be cashing 17,000 checks. Logan also asserts that Abagnale’s time masquerading as a pilot was far shorter than Catch Me If You Can implies, and he couldn’t have been on the run as long as he said he was. In short, Logan told WHYY that he believes that Abagnale’s biggest grift was convincing people his story was true.

It’s also worth noting that Logan isn’t the only one who doesn’t believe Abagnale’s account. A security manager named Jim Keith, who became suspicious of Abagnale after hearing him speak in 1981, compiled an 87-page file of old newspaper articles, letters, and court documents about Abagnale. Keith, who eventually reached out to a New York Post reporter about his discoveries, claimed that the file showed that much of what Abagnale said was “inaccurate, misleading, exaggerated or totally false.”

Abagnale’s former speaking agent, Mark Zinder, even called him a “two-bit criminal,” adding, “I’m embarrassed that I ever associated with the man.”

Back in the day, with longer publishing times and slower news cycles, Abagnale’s most eyebrow-raising anecdotes went largely unchecked, save for a few local journalists who pointed out potential issues, but in the internet age, it became far easier to raise questions about Abagnale’s account.

Abagnale, for his part, has stood by his story. He’s also dismissed Logan’s claims, saying, “I have not read the book, nor do I think it is worthy of a comment.” For some, the lack of a response was all they needed to hear.

After reading about Frank Abagnale Jr., learn about more infamous con artists and the scams they almost got away with. Then, go inside the bizarre origins of the term “snake oil” and how it came to describe a quack remedy.