Otto Frank was the only member of his family to survive the Holocaust and later made the difficult decision to publish his daughter Anne Frank's diaries.

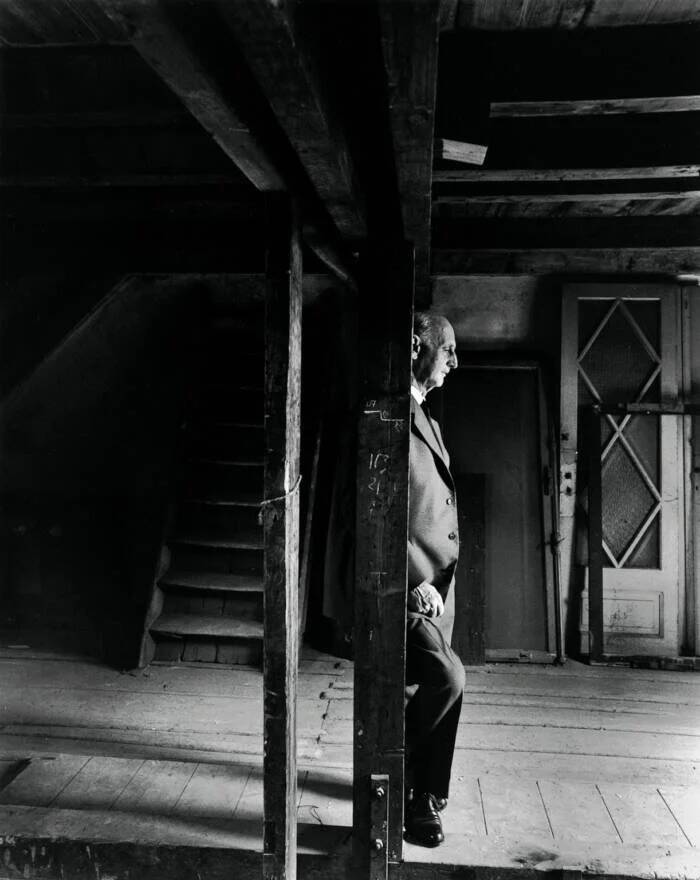

Arnold Newman/Anne Frank HouseOtto Frank in the Secret Annex, shortly before the opening of the Anne Frank House in 1960.

It was the darkest time in modern history: the Holocaust. Nazi leader Adolf Hitler’s “Final Solution” sought to wipe out Europe’s Jewish population — six million of whom were ultimately killed in Hitler’s concentration camps. The tragedy of that number is incomprehensible. But it was brought to life for many by the diaries of Anne Frank — and it’s thanks to her father, Otto Frank, that these diaries were published at all.

One of the most heartbreaking and well-known chronicles of this period, Anne Frank’s diaries recounted how her family went into hiding between 1942 and 1944 in Amsterdam. Though Anne died during the Holocaust at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, her diaries survived. And when Otto returned from his own imprisonment, he decided to have them published.

Today, Anne Frank’s story is well-known across the world. Through her diary entries, readers everywhere were able to gain an intimate understanding of the terrible circumstances she and her family — and by proxy, other Jewish families — went through during this time.

But Otto Frank was more than just a mournful father — and his story is a testament to human perseverance.

Otto Frank’s Life Before The Holocaust

Born on May 12, 1889 in Frankfurt, Otto Frank was the second of four children born to Michael Frank and Alice Betty Stern. According to the Anne Frank House, he came from a family of liberal Jews. They valued Jewish traditions and holidays but did not necessarily observe every religious law.

After Otto graduated high school, he studied art history in Heidelberg, then did a few traineeships at various banks, as well as at Macy’s department store in New York. He returned to Germany in 1909 after his father’s sudden death, then enlisted in the German Army during World War I. Otto served as part of the Lichtmesstrupp, an artillery unit, on the Western Front.

The Anne Frank HouseOtto (left) and his brother Robert during the First World War.

In 1917, Otto was promoted in the field to lieutenant and served in both the Battle of the Somme and the Battle of Cambrai. When the war ended in German defeat, Otto was also awarded the Iron Cross for his service.

Upon his return, he began working at the family bank, and, in 1925, 36-year-old Otto Frank married 25-year-old Edith Holländer, an heiress to a scrap metal and industrial supply business. A year later, on Feb. 16, 1926, their first daughter, Margot, was born. Three years later, on June 12, 1929, Otto and Edith welcomed their second daughter, Anne.

The Anne Frank HouseMargot and Anne as young children.

That same year, Germany was struck hard by the global economic crisis that spawned the Great Depression and plunged people across the world into poverty. It was during this fragile period when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party, riding the wave of dissatisfaction, began to rise to power.

The Frank Family Flees From Germany

Adolf Hitler’s rise to power would transform life in Germany — especially for German Jews. Edith and Otto Frank were so alarmed by the rising antisemitism in their country that they decide to leave Germany in 1933.

They moved their family to Amsterdam, where Otto worked for a pectin (used to make jams) company called Opekta, and Margot and Anne attended Dutch schools. Though the family was doing well, things in Germany continued to get worse. And as Otto toyed with the idea of trying to move the family to Great Britain, Kristallnacht took place in 1938. That same year, Otto Frank decided that his family should leave Europe entirely.

The Anne Frank FondsMargot, Otto, Anne, and Edith Frank in Amsterdam in 1941.

He added his family’s names to the waiting list for American immigration visas — but they were just four of the more than 200,000 Germans who sought to escape to the United States. Immigration was a long process, and the volume of desperate applicants created a backlog.

Two years passed, and, according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Otto had yet to be interviewed by the U.S. consulate. Then things grew much worse. On May 10, 1940, Adolf Hitler and the Nazis invaded Belgium, the Netherlands, and France — destroying the U.S. consulate building and the visa waiting list and bringing the Nazis to the Frank’s doorstep. The Nazis implemented antisemitic laws, forbidding Jews to own companies, for example, and deporting Jews to concentration camps.

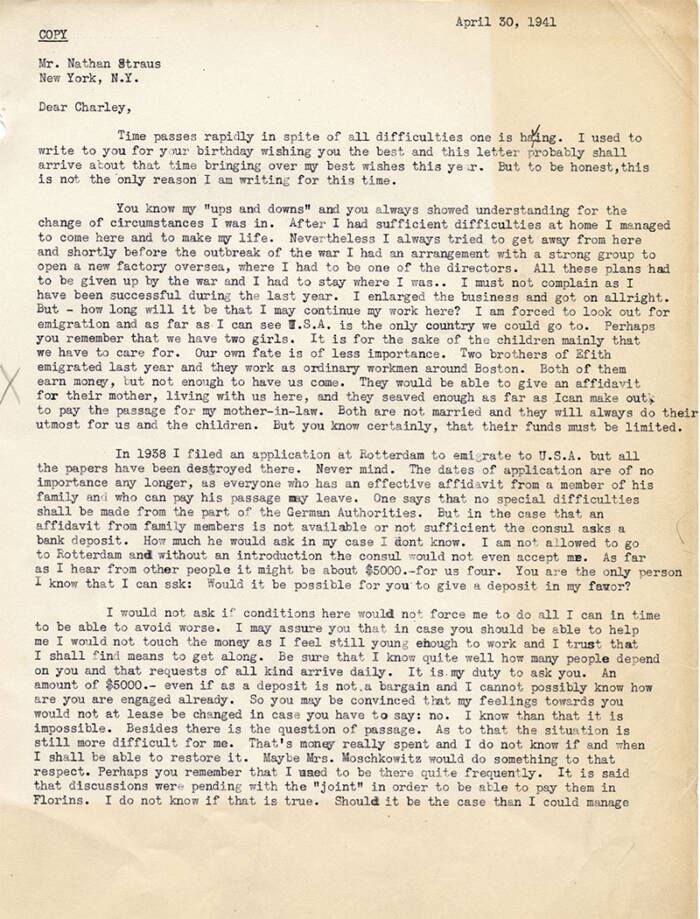

Otto Frank was desperate to get his family away from the Nazis. In April 1941, he wrote to Nathan Straus Jr., the son of the founder of Macy’s, who Otto had befriended during his time in New York. He asked Straus for help — and Straus agreed to try and expedite the Frank family’s immigration process.

The Anne Frank FondsOtto Frank’s letter to Nathan Straus Jr., referred to as Charley by his friends.

Six weeks later, on June 11, 1941, Straus signed five copies of an affidavit for the Frank family and agreed to sponsor their immigration to America. Despite his haste, however, the process was delayed by new rules implemented by the U.S. State Department. Then Germany ordered that U.S. consulates in Nazi-occupied territories be shut down — and when the U.S. joined World War II following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, immigration to the U.S. became an impossibility.

“It is a pity that for the present all efforts will be useless as the American Consulate at Rotterdam is leaving… So we have to wait,” Otto Frank wrote in a grim letter to Straus. “Bad luck, but cannot be helped. Let us hope that conditions will get more normal again.”

Yet conditions only continued to worsen, and when it became clear that the Franks were in imminent danger, they had just one option left: to hide.

How The Franks Hid From The Nazis In The Secret Annex For Two Years

In July 1942, the Franks received word that Margot was to be sent to a labor camp in Nazi Germany — and they decided to take immediate action. Fortunately, Otto Frank had been making plans to go into hiding alongside the family of his employee, Hermann van Pels, at his company building.

With the aid of several friends and colleagues, including Miep Gies, the Franks moved into an annex hidden at Prinsengracht 263 on July 6, 1942. The van Pels family joined them a week later, and an eighth person, Fritz Pfeffer, moved in that November. Though momentarily sheltered from the Nazis, tensions soon grew between the eight people living there.

“We had thought that living with my partner’s family in our hiding place would make life less monotonous,” Otto later reflected of life in the annex, “but we had not foreseen how many problems would arise because of the differences in characters and views.”

Desk/AFP/Getty ImagesThe building at Prinsengracht 263 where the Frank family hid from the Nazis.

Despite the tension, however, the families would remain hidden together for more than two years. And Anne Frank, who started writing in her diary on June 14, 1942, recorded what life was like.

“I expect you will be interested to hear what it feels like to hide; well, all I can say is that I don’t know myself yet,” Anne wrote in her diary on July 11, 1942. “I don’t think I shall ever feel really at home in this house but that does not mean that I loathe it here, it is more like being on vacation in a very peculiar boardinghouse. Rather a mad way of looking at being in hiding perhaps but that is how it strikes me.”

Tragically, Prinsengracht 263 was suddenly raided on August 4, 1944 and its occupants were arrested. Someone had betrayed the Franks and the others, but to this day it is unknown who gave up their hiding place.

The Frank family and the others were sent to the Westerbork transit camp, where the men and women were separated during the day. They could see each other at night, but after only a few weeks they were sent off once again, this time to the Auschwitz concentration camp. The men and women were once again separated, and this time it was permanent.

Otto Frank never saw his family alive again.

Otto Frank Survives Auschwitz-Birkenau

Public DomainPrisoners arriving at Auschwitz in the spring of 1944.

Otto Frank, like most of the other men at the camp, was initially put to work, first mining gravel, then building roads, and finally peeling potatoes. He and his fellow inmates formed a deep kinship, and it was thanks to their support — particularly the support of Peter van Pels — that Otto survived.

He fell ill in November 1944, which meant he was no longer able to do manual labor. This proved to be a blessing in disguise. Otto Frank was transferred to the sick bay where he was protected from the cold, and thanks to Peter van Pels, he was able to get extra food. Still, he was losing weight rapidly. At his thinnest, he weighed just 114 pounds.

But salvation came on Jan. 27, 1945, when the Soviet Army arrived to liberate Auschwitz.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Courtesy of NARAAuschwitz prisoners watching their liberators.

Just 10 days earlier, the SS had begun emptying the camps, forcing prisoners to walk until they either died or could be taken to another camp as the Nazis tried to scrub the camps of any evidence of their crimes. Peter van Pels was among those forced to walk in the snow, and he eventually died at the Mauthausen concentration camp at the age of 18.

Otto Frank was spared this long walk, but that hardly meant he was safe. He and the other sick prisoners were supposed to have been executed by firing squads, but because the SS were in such a rush to leave, the squad was called away. Within a few days, the camp was mostly abandoned, save the 7,700 prisoners who had been left behind. They struggled to stay warm and share food amongst themselves for a week before the Soviets arrived.

The arrival of the Soviet army marked the end of Nazi occupation, and shortly afterward the Polish Red Cross constructed a hospital to tend to the sick prisoners. Otto Frank was one of the men nursed back to health. He finally left Auschwitz on March 5.

Immediately, he went to look for his family.

The Publication Of Anne Frank’s Diary

Public DomainAnne Frank writing. Circa 1940.

Upon his return to Amsterdam, Otto Frank reconnected with Miep Gies and learned that he was the only survivor from his family. Something else had survived, though too — Anne’s diary. Gies had held onto it, planning to give it to Anne when she returned.

Instead, she gave the diary to Otto.

Although reading through her diary was painful, it was also cathartic. Otto knew his daughter wanted to one day publish her writings, and so, after some initial hesitation, he compiled her diary into a manuscript.

Today, Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl has been read by more than 30 million people worldwide and has been translated into more than 70 languages. In many schools, it is required reading.

Andrew Burton/Getty ImagesA copy of Anne Frank’s diary, published under the title, The Diary of a Young Girl.

Otto spoke about Anne’s diary in a 1979 interview, calling it a “testament” and a “message against racism, antisemitism, and for understanding people.” He died of lung cancer one year later, on August 19, 1980, in Birsfelden, Switzerland.

In that same interview Otto Frank stated: “Unfortunately, humanity generally does not learn from the past. But those who can, must contribute to increasing understanding of it, so that lessons can be learned from the past. I still receive letters every day from readers worldwide about Anne’s diary… That’s why I can truly say that Anne’s diary is a document humain. Its content touches people, no matter where they live.”

After reading about the life of Otto Frank, read all about how these nine people became heroes of the Holocaust. Or, take a look into the Warsaw ghetto that was once home to more than 350,000 Jews.