Gary Webb was a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter, but the media did everything it could to discredit his three-part exposé that revealed links between the CIA, the revolution in Nicaragua, and the crack epidemic that gripped Los Angeles in the 1980s.

In a three-part exposé printed in the San Jose Mercury News in 1996, investigative journalist Gary Webb reported that a guerrilla army in Nicaragua had used crack cocaine sales in Los Angeles’ Black neighborhoods to fund an attempted coup of Nicaragua’s socialist government in the 1980s — and that the CIA had purposefully funded it.

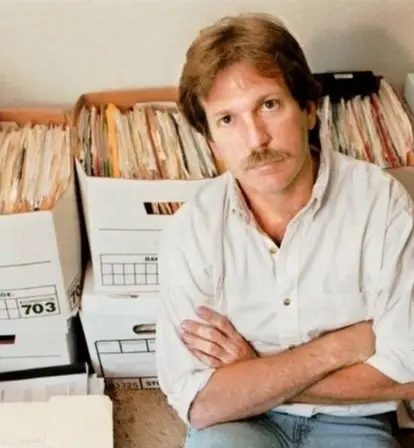

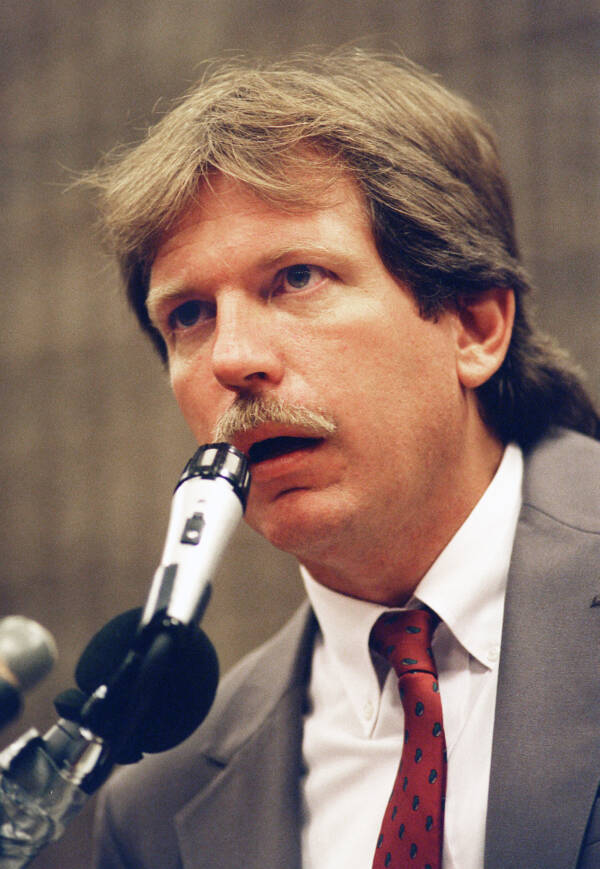

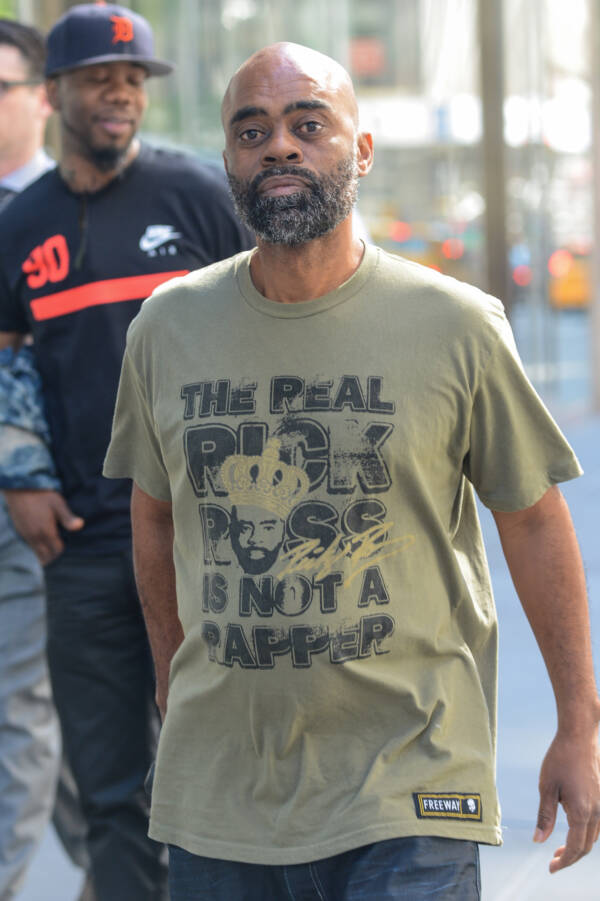

Scott J. Ferrell/Congressional Quarterly/Getty ImagesGary Webb speaking at the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation Annual Legislative Conference. He participated in a panel discussion called “Connections, Coverage, and Casualties: The Continuing Story of the CIA and Drugs.” Sept. 11, 1997.

The series of reports set off a firestorm of protests in L.A. and Black communities across the country as African Americans became outraged by the assertion that the U.S. government could have supported — or at least turned a blind eye to — a drug epidemic that had ravaged their population while at the same time incarcerating a generation with Ronald Reagan’s “War on Drugs.”

Gary Webb’s reporting was quickly discredited by major newspapers like The New York Times, and even his own employers turned their back on him. The CIA, amid a public relations nightmare, broke its policy of not commenting on any individual’s agency affiliation and denied Webb’s story entirely. He was demoted, and in 2004, he died by suicide.

However, an investigation into the CIA revealed that Webb may not have been wrong after all.

The ‘Dark Alliance’ Uncovered By Journalist Gary Webb

In the mid-1990s, Gary Webb set out to challenge “the widely held belief that crack use began in African American neighborhoods not for any tangible reason but mainly because of the kind of people who lived in them,” as Webb wrote in a chapter for the 2004 book Into the Buzzsaw: Leading Journalists Expose the Myth of a Free Press. He continued:

“Nobody was forcing them to smoke crack, the argument went, so they only have themselves to blame. They should just say no. That argument never seemed to make much sense to me because drugs don’t just appear magically on street corners in Black neighborhoods. Even the most rabid hustler in the ghetto can’t sell what he doesn’t have. If anyone was responsible for the drug problems in a specific area, I thought, it was the people who were bringing the drugs in.”

Those people, he found, were backed by the CIA.

The so-called “Dark Alliance” that Webb purportedly unveiled consisted of a group of rebels trying to overthrow the socialist government of Nicaragua. These Contras were funded by a Southern California drug ring and backed by the CIA.

“For the better part of a decade, a San Francisco Bay Area drug ring sold tons of cocaine to the Crips and Bloods street gangs of Los Angeles and funneled millions in drug profits to an arm of the Contra guerrillas of Nicaragua run by the Central Intelligence Agency.”

The U.S.-backed dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza Debayle in Nicaragua came to an end with the Sandinista Revolution of 1978 and 1979. With no legal recourse to topple the five-person junta that took Somoza Debayle’s place, CIA interests had to find alternative means to plant a figurehead of their choosing.

President Ronald Reagan allocated $19 million to set up a U.S.-trained paramilitary force of 500 Nicaraguans that eventually became known as the Contras. But in order to topple the Sandinistas, the Contras needed a lot more weapons — and a lot more money. And to get that money, they needed to look beyond foreign aid.

Jason Bleibtreu/Sygma/Getty ImagesTeenage Contra rebels at a training camp in Nicaragua. The guerrilla group was created to oust the country’s socialist government.

Soon enough, according to Gary Webb, Contra officials set their sights on the poor, Black neighborhood of South Central Los Angeles — and rendered it ground zero of the 1980s crack epidemic.

Webb’s reporting, focused on a few central players of the L.A. coke scene and the Contra rebels, illustrated how a CIA-backed war in South America devastated Black communities in southern California and across the country.

At worst, Webb claimed, the CIA orchestrated the drug ring. At best, they knew about it for years and did absolutely nothing to stop it — all the better to serve the United States’ economic and political interests abroad.

How The U.S. Government Allegedly Shepherded Drug Traffickers To Safety

One of the most notable street-level players involved in this “Dark Alliance” was Oscar Danilo Blandón Reyes, a former Nicaraguan bureaucrat-turned-prolific cocaine supplier in California. From 1981 to 1986, Blandón seemed to be protected by invisible higher-ups who quietly held jurisdiction over local authorities.

After six years of shepherding thousands of kilos of cocaine worth millions of dollars to the Black gangs of L.A. during the early 1980s without a single arrest, Blandón was busted on drugs and weapons charges on Oct. 27, 1986.

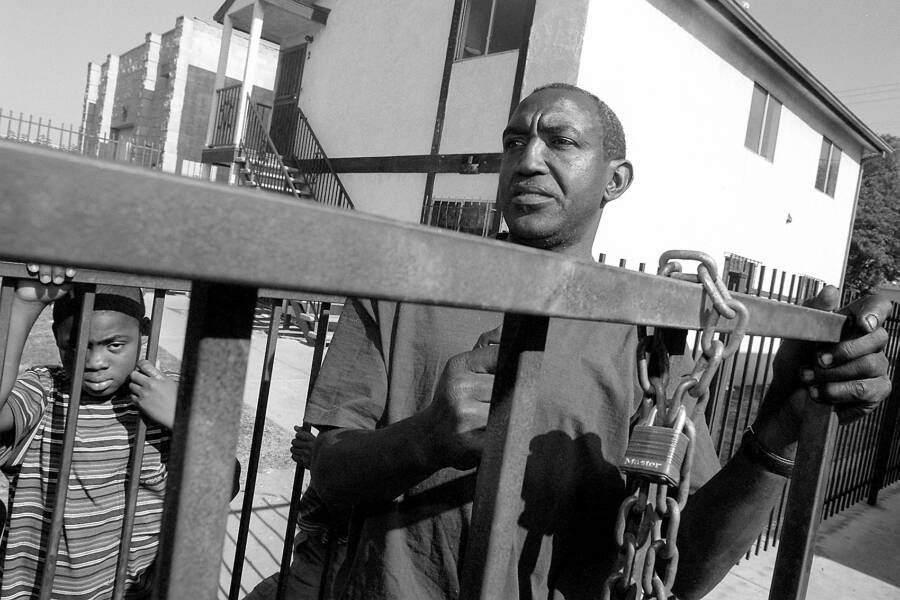

Luis Sinco/Los Angeles Times/Getty ImagesDonald Shorts, a mechanic and resident of South Central Los Angeles, blamed the crack epidemic that washed through the city on the complicity of the CIA and the lack of employment opportunities for Black youth.

In a written statement to obtain a search warrant for Blandón’s sprawling cocaine operation, L.A. County Sheriff’s Sergeant Tom Gordon confirmed that local drug agents knew about Blandón’s involvement with the CIA-backed Contras.

Per Gary Webb’s 1998 book Dark Alliance: The CIA, the Contras, and the Crack Cocaine Explosion, Gordon stated in an affidavit that “monies gained from the sales of cocaine are transported to Florida and laundered through Orlando Murillo, who is a high-ranking officer of a chain of banks in Florida named Government Securities Corporation. From this bank the monies are filtered to the Contra rebels to buy arms in the war in Nicaragua.”

All of this and more was later backed up by Blandón himself, after he became an informant for the DEA and took the stand as the Justice Department’s key witness in a 1996 drug trial. He testified that his drug ring sold close to one ton of cocaine in the U.S. in 1981 alone. In the following years, as more and more Americans became hooked on crack, that figure skyrocketed.

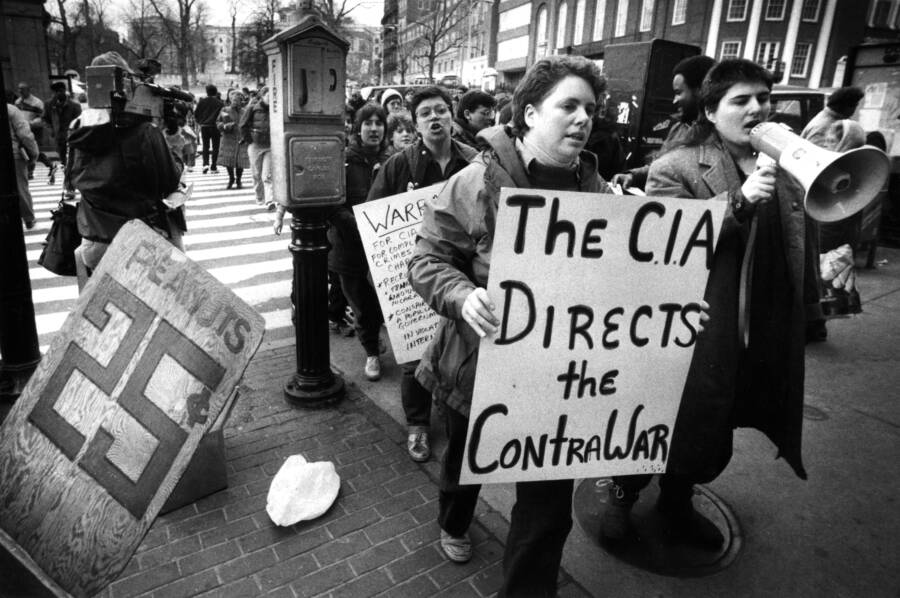

Tom Landers/The Boston Globe/Getty ImagesProtestors march outside of the CIA’s Boston offices in the middle of winter to demonstrate against the war in Nicaragua. March 2, 1986.

While he wasn’t sure how much of that money went to the CIA, Blandón said that “whatever we were running in L.A., the profit was going for the Contra revolution.”

Blandón’s work had devastating consequences. L.A.’s drug lords had come up with a way to make cocaine cheaper and more potent: cooking it into “crack.” And nobody spread the plague of crack as far and wide as Ricky Donnell “Freeway Rick” Ross.

Freeway Rick And The Crack Capital Of The World

According to a 2013 article in Esquire, Freeway Rick raked in more than $900 million in the 1980s, with a profit encroaching on $300 million (nearly $1 billion in today’s currency).

His empire ultimately grew to 42 U.S. cities, but it all came tumbling down after Blandón, his main supplier, turned into a confidential informant.

Webb first heard of Ross while researching asset forfeitures in 1993 and found he was “one of the biggest crack dealers in L.A.” He then discovered that Blandón was the informant who got Ross imprisoned in 1996.

When Gary Webb realized that Blandón — the fund-raiser for the Contras — sold cocaine to Ross, South Central L.A.’s biggest crack dealer, he had to speak to him. He eventually got Ross on the phone and asked him what he knew about Blandón. Ross had only known him as Danilo and figured he was a regular guy with an entrepreneurial streak.

Ray Tamarra/GC Images“Freeway” Rick Ross didn’t know how to read until he taught himself at the age of 28 while imprisoned. It was as a direct result that he noticed a flaw in his conviction, which subsequently led to a successful appeal. June 24, 2015. New York City, New York.

“He was almost like a godfather to me,” said Ross, according to Webb’s book. “He’s the one who got me going. He was [my main source]. Everybody I knew, I knew through him. So really, he could be considered as my only source. In a sense, he was.”

Ross confirmed to Gary Webb that he met Blandón in 1981 or 1982, right around the time Blandón started dealing drugs. Webb spent hours talking with Ross at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in San Diego, where he found that Ross knew nothing about Blandón’s past at all.

He didn’t even know who the Contras were or who was financing their war. To Ross, Blandón was just a smooth-talking guy with an unending stash of cheap cocaine.

Bill Gentile/Corbis/Getty ImagesContra forces move down the San Juan River (which separates Costa Rica from Nicaragua). “Freeway” Rick Ross said he was entirely unaware his rampant drug dealing in L.A. was funding this group of anti-Sandinistas in Central America.

When Webb told Ross that Blandón had worked for the Contras, selling drugs to finance their weapons supplies, Ross was flabbergasted.

“And they put me in jail? I’d say that was some f—ked up sh—t there,” said Ross. “They say I sold dope all over, but man, I know he done sold 10 times more than me… He’s been working for the government the whole damn time.”

The Problems With Gary Webb’s Reporting

While Gary Webb’s sources were seemingly legitimate, there were certainly problems with his writing and reporting. As Peter Kornbluh laid out in the Columbia Journalism Review in 1997, Webb presented some powerful evidence that two Contra-affiliated Nicaraguans became prolific drug smugglers in the 1980s U.S.

But when it came to the most enticing bit of the story and the part that most animated and enraged the American public — that these smugglers were linked to the CIA — there was, on a closer reading, very little direct evidence.

In all 20,000 words of “Dark Alliance,” Gary Webb never claimed outright that the CIA knew about the Contras’ drug scheme, but he certainly implied as much. It was clear that Blandón had connections to the Contras, and it was a known fact that Contra forces were backed by the CIA, but Webb failed to make a compelling case for Blandón’s direct connection to the U.S. government agency.

Mike Nelson/AFP/Getty ImagesU.S. Rep. Maxine Waters, representing a majority-minority district in Los Angeles, holds up an apparent package of cocaine for the press. She pushed the government to investigate Webb’s findings. Oct. 7, 1996.

“To some this may seem a trivial distinction,” Kornbluh wrote. U.S. Representative Maxine Waters said at the time that “it doesn’t make any difference whether [the CIA] delivered the kilo themselves, or they turned their heads while somebody else delivered it, they are just as guilty.”

But, in the words of Kornbluh, “the articles did not even address the likelihood that CIA officials in charge would have known about these drug operations.” Failing to do so — and crafting the whole piece as a one-sided, damning report without presenting contradictory evidence — was a major oversight by Webb and his editors, and it made his exposé wide open to criticism.

How Major Newspapers Poked Holes In Gary Webb’s Exposé

That criticism came like a tidal wave. While some Bay Area papers and talk radio shows pounced on the story, the country’s major newspapers and TV news networks remained mostly silent at first.

“Dark Alliance” was breaking internet records, boasting 1.3 million site visits daily — a remarkable feat at a time when only about 20 million Americans had home internet access. Then, on Oct. 4, The Washington Post published a scathing “investigation” declaring that “available information does not support the conclusion that the CIA-backed Contras — or Nicaraguans in general — played a major role in the emergence of crack as a narcotic in widespread use across the United States.”

A couple of weeks later, The New York Times released a declaration that there was “scant proof” for Webb’s main contentions.

Bob Berg/Getty ImagesThe CIA denied Gary Webb’s reporting, and his fellow journalists nitpicked Webb’s faults while failing to follow up on his claims. Los Angeles. March 1999.

But the greatest criticism came from the Los Angeles Times, which assembled a 17-person team known as the “get Gary Webb team.” On Oct. 20, the L.A. paper — incensed that it had been scooped in its own backyard — began publishing a three-part series of its own.

All three papers ignored evidence already out there, including a Senate Subcommittee report from 1989 that found that “U.S. officials involved in Central America failed to address the drug issue for fear of jeopardizing the war efforts against Nicaragua.”

The media’s penchant for jealousy and cannibalism worked in the CIA’s favor. Rather than mounting a stealth public relations campaign, all the agency had to do was provide reporters with comments of denial. Journalists didn’t need to be convinced to go after Webb — they did it gladly.

“Clearly, there was room to advance the Contra/drug/CIA story rather than simply denounce it,” Kornbluh wrote. Instead of investigating the questions Gary Webb raised and providing crucial information to an enraged public that had been devastated by crack addiction and the War on Drugs, the “big three” papers made it their main goal to discredit Webb.

Kill The Messenger: The Death Of Gary Webb

While Webb’s own employer, the Mercury News, initially supported him, they, too, turned their back on him in the end. Jerry Ceppos, then the executive editor of the Mercury News, wrote an open letter to readers rescinding support for Webb’s reporting and listing the editorial flaws in “Dark Alliance.”

The news media took his apology and put it on blast. Webb, who just a few years prior had won a Pulitzer Prize, was reassigned and essentially demoted. He resigned from the paper by the end of the year, and his reputation was so tarnished that he couldn’t get a good job anywhere else.

He was forced to sell his home in 2004, but on moving day, he shot himself in the head.

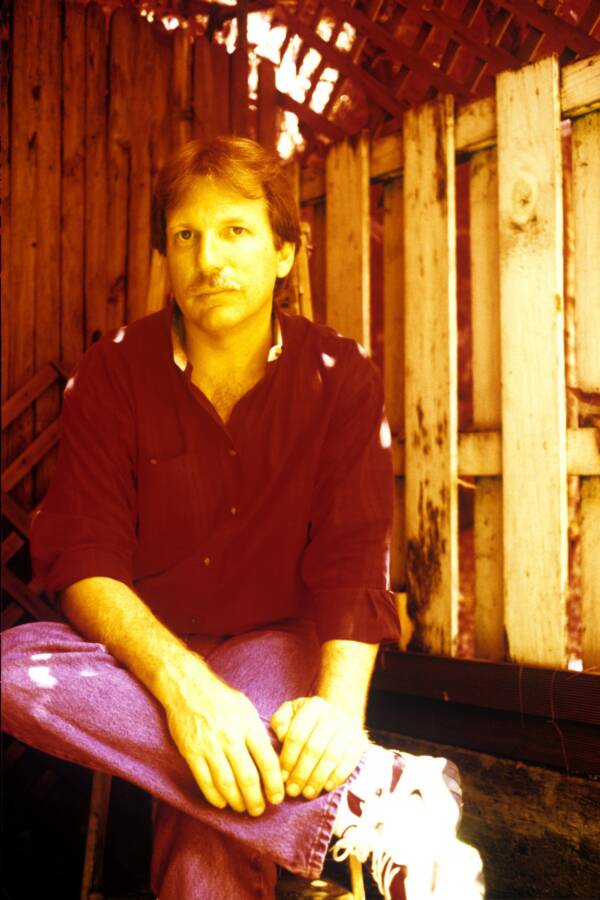

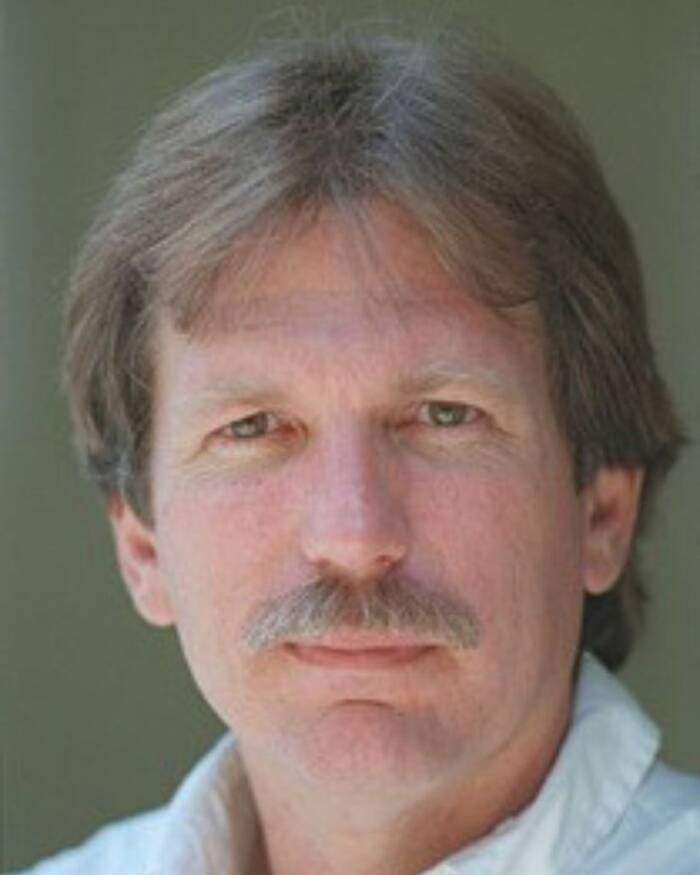

Wikimedia CommonsDiscredited and unable to find steady employment in the journalism field, Gary Stephen Webb died by suicide on Dec. 10, 2004, at age 49.

Webb’s reporting ultimately panned out: We now know that the U.S. government was complicit in drug smuggling in order to support its foreign policy interests. In March 1998, CIA Inspector General Fred Hitz spoke to the House Intelligence Committee about his own investigation into Webb’s allegations.

“Let me be frank about what we are finding,” Hitz said. “There are instances where the CIA did not, in an expeditious or consistent fashion, cut off relationships with individuals supporting the Contra program who were alleged to have engaged in drug trafficking activity.”

It was a phenomenon that, combined with the War on Drugs, devastated large and mostly Black swaths of Americans for generations. Still, even though Webb was mostly right, the media’s response to the journalist’s “Dark Alliance” spelled his doom.

After reading about Gary Webb exposing the CIA’s potential complicity in L.A.’s crack epidemic, learn all about Nellie Bly, the pioneering investigative journalist who faked insanity to expose the inner workings of a Victorian-era asylum. Then take a look at 37 startling photos of 1980s New York City, when crack was king.