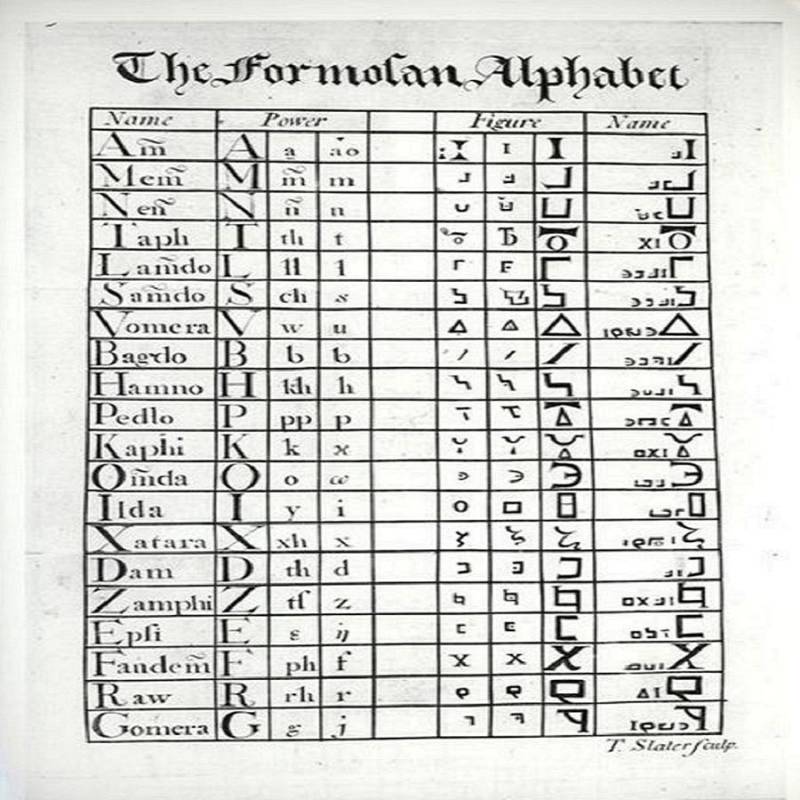

Character Development

Wikimedia CommonsA page of Psalmanazar’s primer on the Formosan language, which he completely invented from scratch and then taught to missionaries on their way to the island.

By the time that Psalmanazar crossed the Rhine into what is now Germany, he was posing as a displaced heathen from Japan, despite being blond with blue eyes and not speaking a word of Japanese. Europe in 1700 wasn’t very picky about details like that, so Psalmanazar got by on what he’d learned from the Jesuit missionaries he had known who had actually been to the Far East.

To make the imposture more believable, Psalmanazar took up sleeping in chairs and worshiping the Sun, as were customs of the Japanese people.

Perhaps looking to avoid another embarrassing exposure, by 1702 he had again adjusted his place of origin from Japan, which maybe one European in a thousand knew something about, to Formosa, modern-day Taiwan, which nobody knew about at all.

To add a bit of spice, he even invented and observed his own calendar and performed bizarre religious rituals whenever he thought someone might be looking. He even started speaking a gibberish language and giving people blessings in “Formosan.”

By the end of the year, Psalmanazar had mooched all the way to the Netherlands, which was conveniently involved in a holy war against various Catholic countries and allied with England. There, he met a British chaplain attached to a Scottish regiment named Alexander Innes. Innes fell for the “Formosan savage” routine so hard he left a dent in the floor.

It was Innes who baptized the “heathen” into the Church of England and christened him “George Psalmanazar,” allegedly a reference to King Shalmaneser of the Bible. In 1703, Innes had written the necessary letters of introduction and was escorting his exotic new convert to London to meet all of the important people of the realm, starting with the Bishop of London. Psalmanazar would not let them down.

The Nature of a Successful Fraud

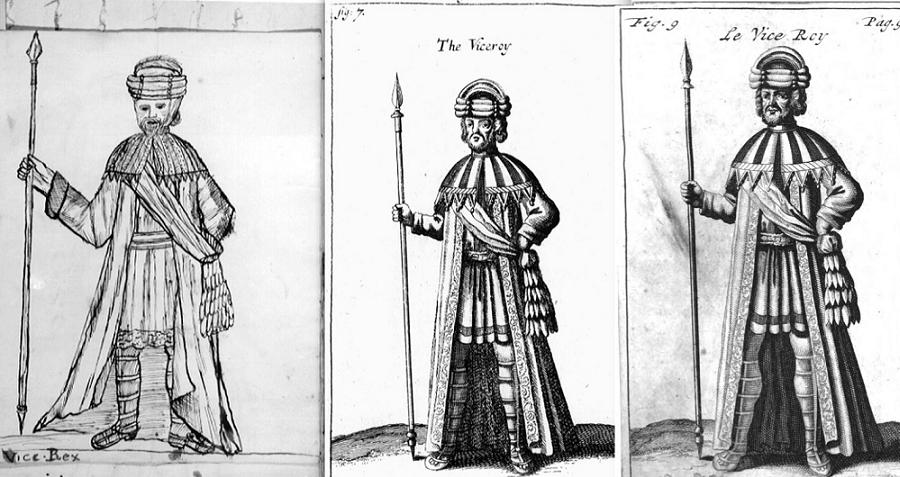

Wikimedia CommonsThree images of a “Formosan Viceroy.” The one on the left is Psalmanazar’s own sketch, while the other two are from the British and French editions of his book.

Psalmanazar’s invented backstory was absurd in the highest degree. Eighteenth century or not, anybody should have been able to see through it, or at least to discern that something wasn’t right.

For example, according to the story he told, he had been born to the Formosan aristocracy and never went outdoors, which is why his skin was so white. He also claimed that the Formosans annually sacrificed 20,000 virginal boys on a large outdoor grill, and that he had been kidnapped by Jesuits as a child.

He even told the Bishop of London that the priests had tortured him to try and force him to accept Catholicism, but that he had known it was a false doctrine from the start and that only Anglicanism was truly convincing, hence his conversion.

It’s been said that you can’t cheat an honest man, which is usually taken to mean that people being lied to always partly lie to themselves.

In early-18th century England, people’s interest in and ignorance of the Far East created a fertile ground for Psalmanazar to exploit, and the lies he told were finely calibrated to match every prejudice that the British wanted to hear reinforced: Their religion is convincing to people from far-off lands, Catholics (especially Jesuits) are evil, British culture can civilize pagans, aristocrats all over the world look white.

Psalmanazar fed them all exactly what they liked to hear. Even when he debated a visiting Jesuit theologian, the crowd came away convinced that Psalmanazar had won because of how glib his answers had been and how he had a ready – and pro-British – explanation for every inconsistency that the priest had brought up.