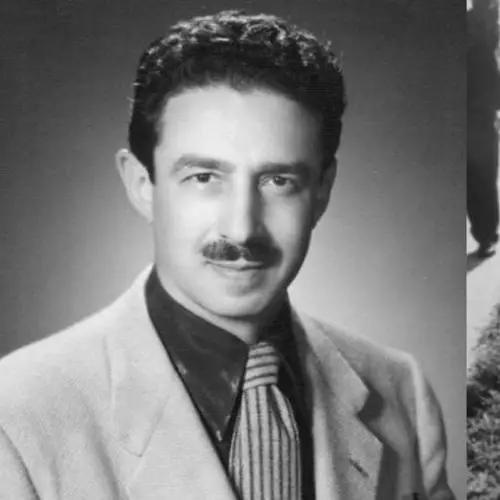

Neurologist Walter Freeman introduced the lobotomy to the United States in 1936, but over the next three decades, the controversial procedure left an estimated 490 of his patients dead and permanently disabled many others.

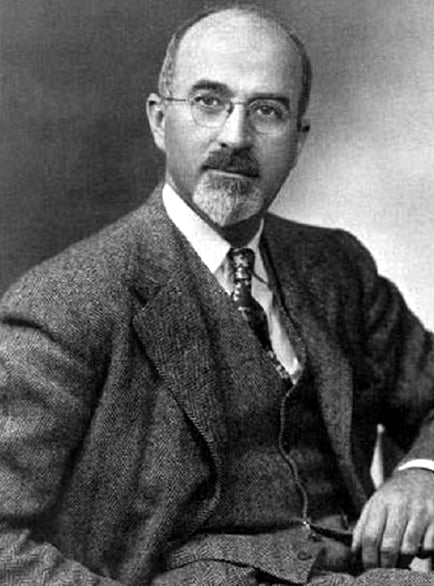

National Library of MedicineWalter Freeman invented the controversial transorbital lobotomy and popularized its usage across the United States.

Walter Freeman intended to revolutionize the treatment of mental illnesses. Instead, he killed hundreds of his patients and went down in history as the man who introduced a truly barbaric surgery to the United States: the lobotomy.

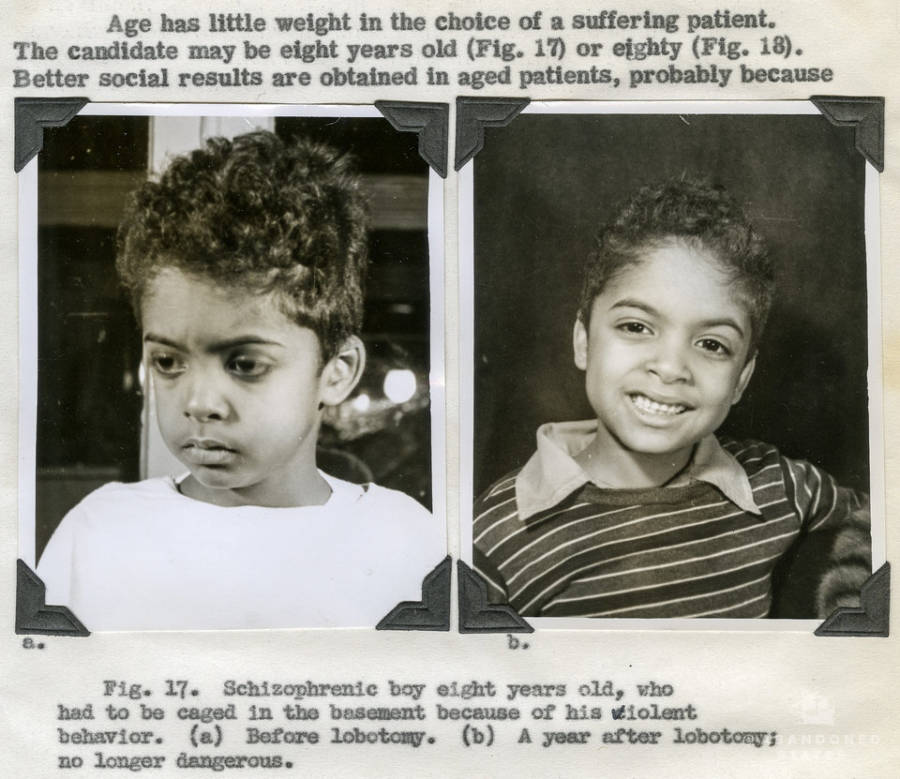

On Sept. 14, 1936, Freeman and his partner, neurosurgeon James W. Watts, performed America’s first lobotomy. Over the next six years, they carried out the procedure more than 200 times to mixed results. The doctors even infamously lobotomized Rosemary Kennedy in 1941, leaving her with the mental capacity of a toddler.

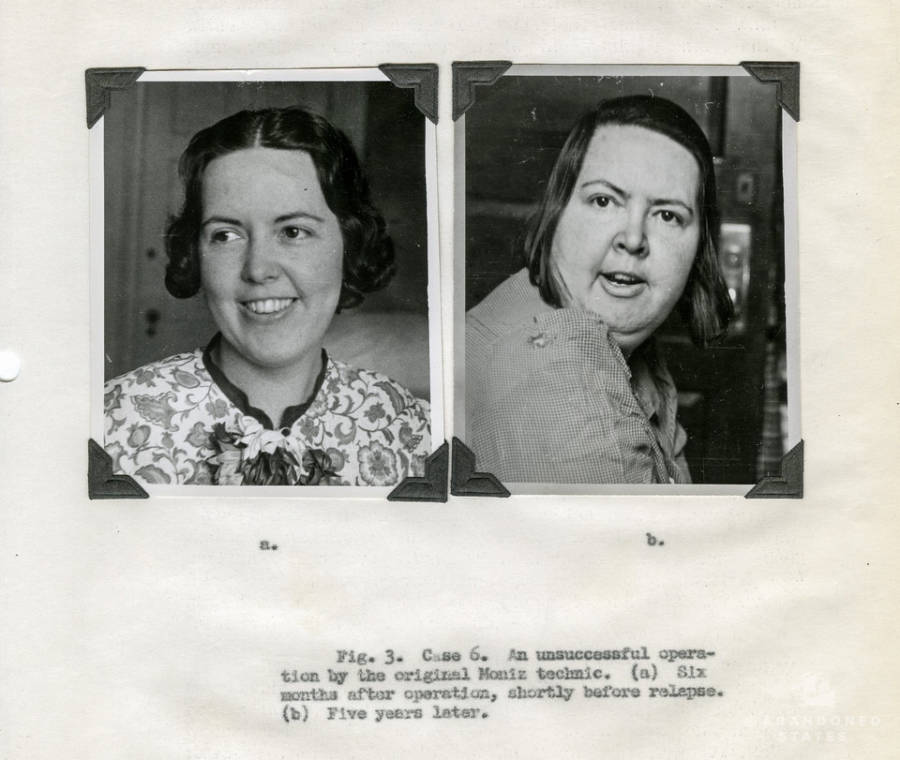

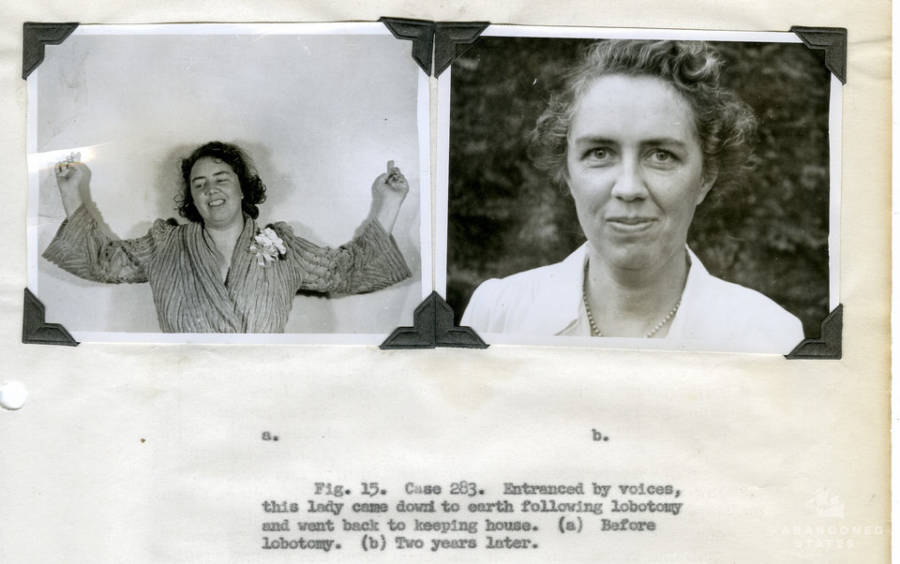

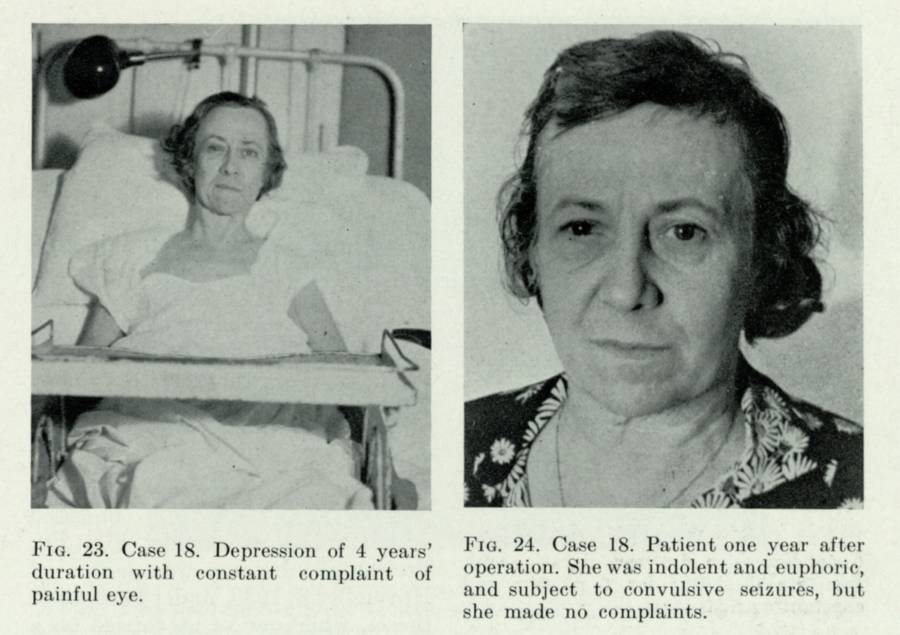

Rosemary wasn’t the only victim who was irreversibly altered by the operation, though. Just 63 percent of Watts and Freeman’s patients reported an improvement in their disorders, while 14 percent experienced worsening symptoms.

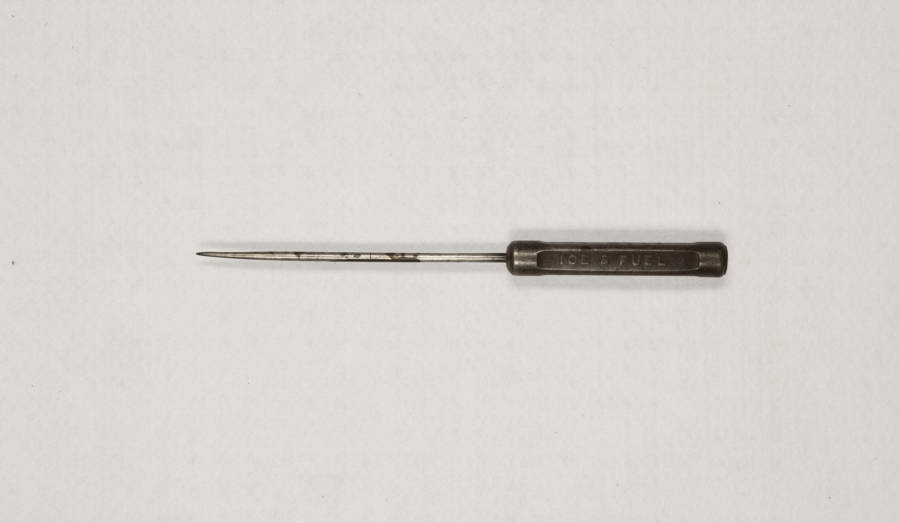

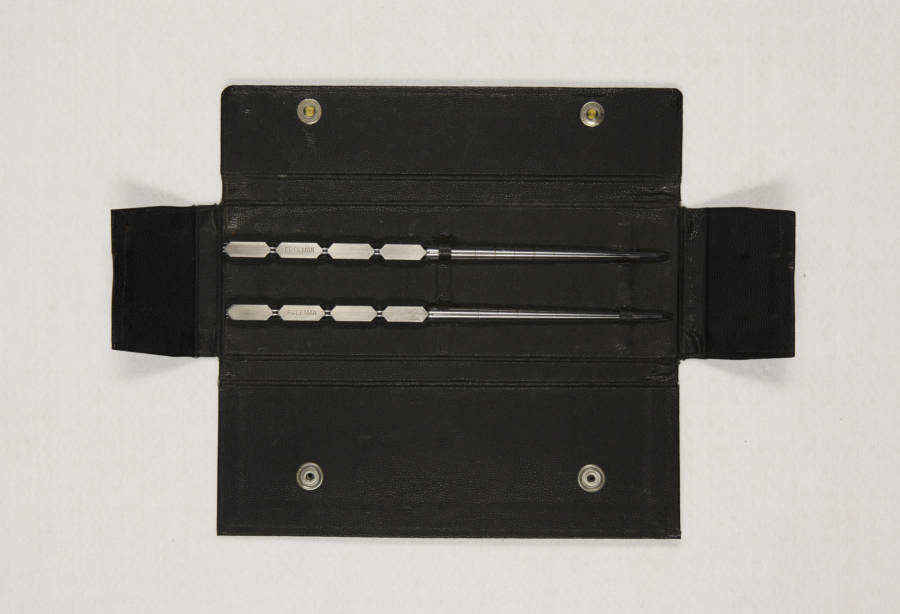

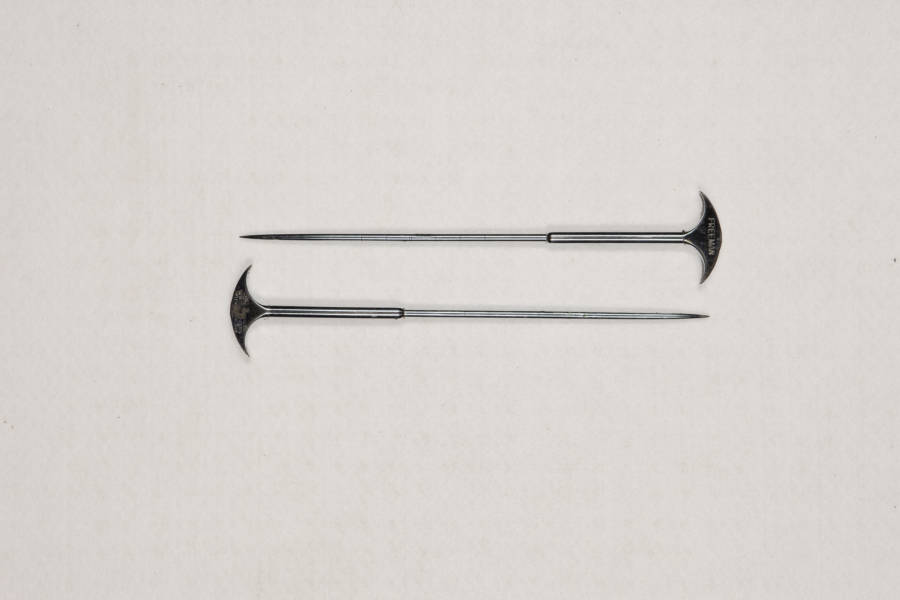

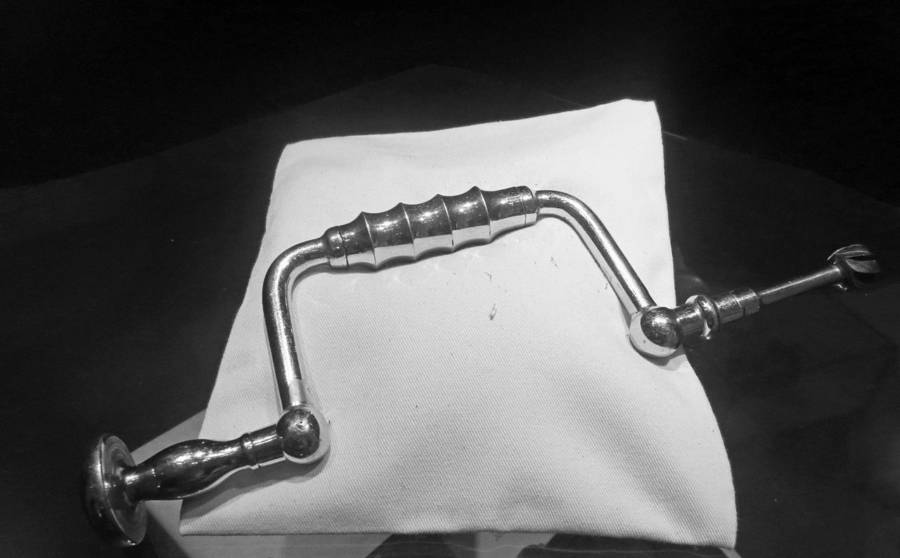

Unhappy with these results, Walter Freeman set out to develop his own version of the surgery known as the transorbital lobotomy. Instead of drilling through the skull, Freeman inserted instruments that were similar to ice picks through his patients’ eye sockets and into their brains — and he did it without general anesthesia.

By 1967, Freeman had supervised or personally carried out an estimated 3,500 lobotomies. Nearly 500 of those patients died, and many others suffered fates similar to Rosemary Kennedy. Freeman was ultimately banned from performing the surgery, but his story remains a haunting reminder of a dark chapter in medical history.

Walter Freeman's Upbringing And Education

American neurologist Walter Jackson Freeman II was born in Philadelphia in 1895. His grandfather, William Williams Keen, was the first brain surgeon in the United States, and his father, Walter J. Freeman, was also a distinguished physician. Growing up, Freeman was naturally inclined to follow in their footsteps.

After graduating from Yale in 1916, Walter Freeman went on to study neurology at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School. He then traveled to Europe to further his education in the field in 1923, and when he returned to the United States the following year, he established himself as the first practicing neurologist in Washington, D.C.

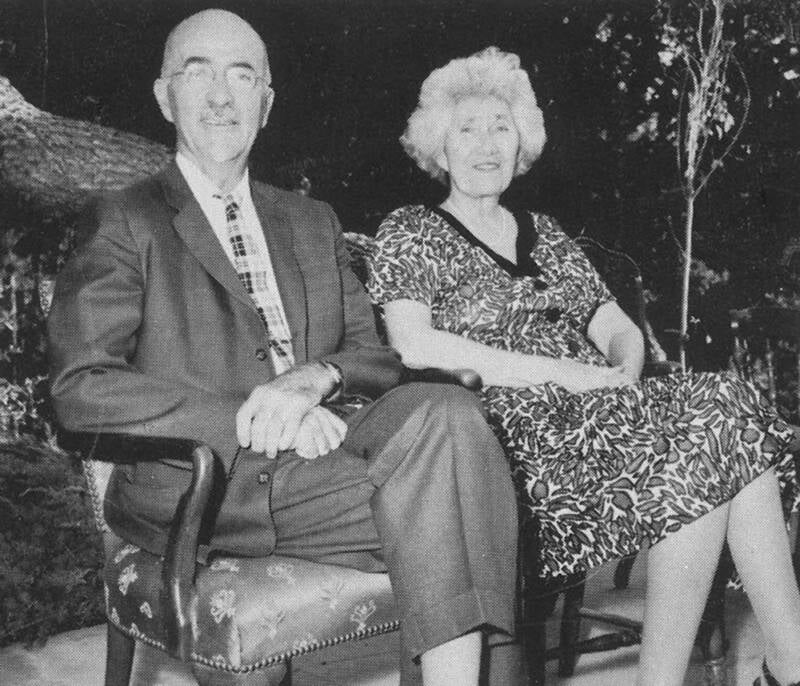

Stanford University Medical Center RecordsWalter Freeman with his wife, Marjorie.

By the early 1930s, Walter Freeman had directed the laboratories at St. Elizabeths Hospital, earned a Ph.D. in neuropathology, and accepted a position as the head of the neurology department at George Washington University. However, there was still much more he wanted to do.

During his time at St. Elizabeths, a psychiatric hospital, Freeman witnessed the immense pain and suffering the patients there experienced. He was determined to seek out an effective treatment that could help people struggling with mental illness and psychological disorders — and he eventually found one in Portugal.

Bringing The Lobotomy To The United States

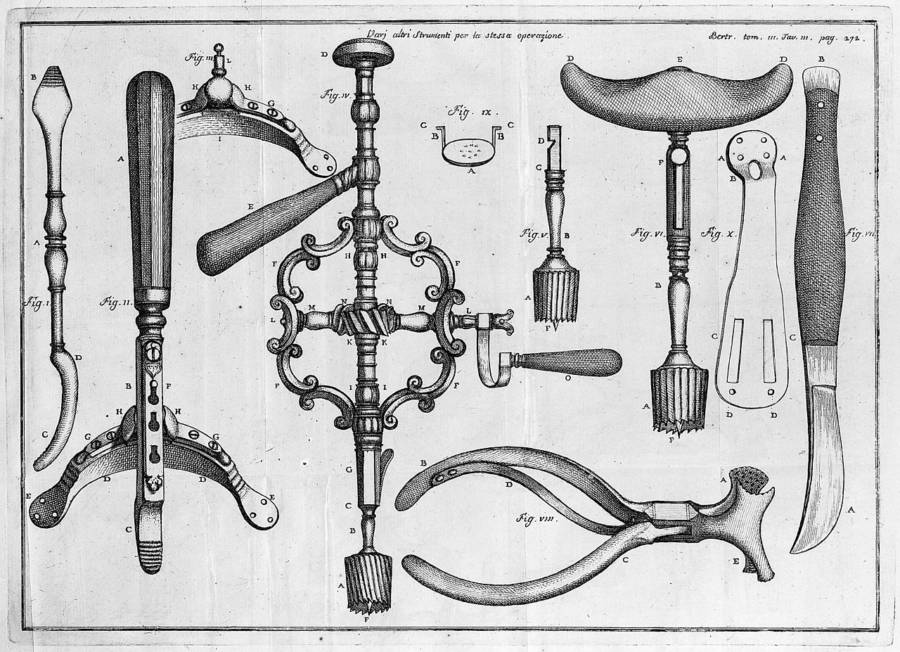

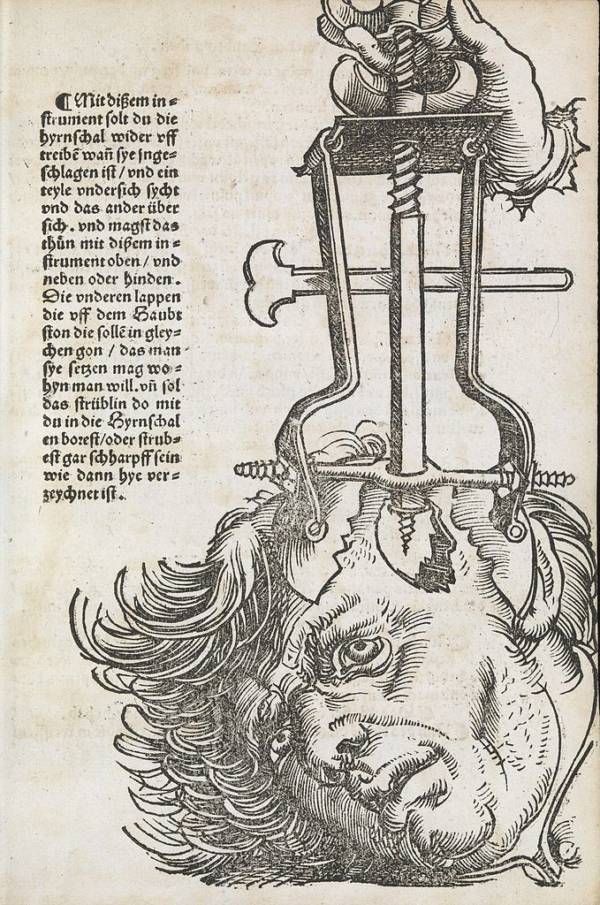

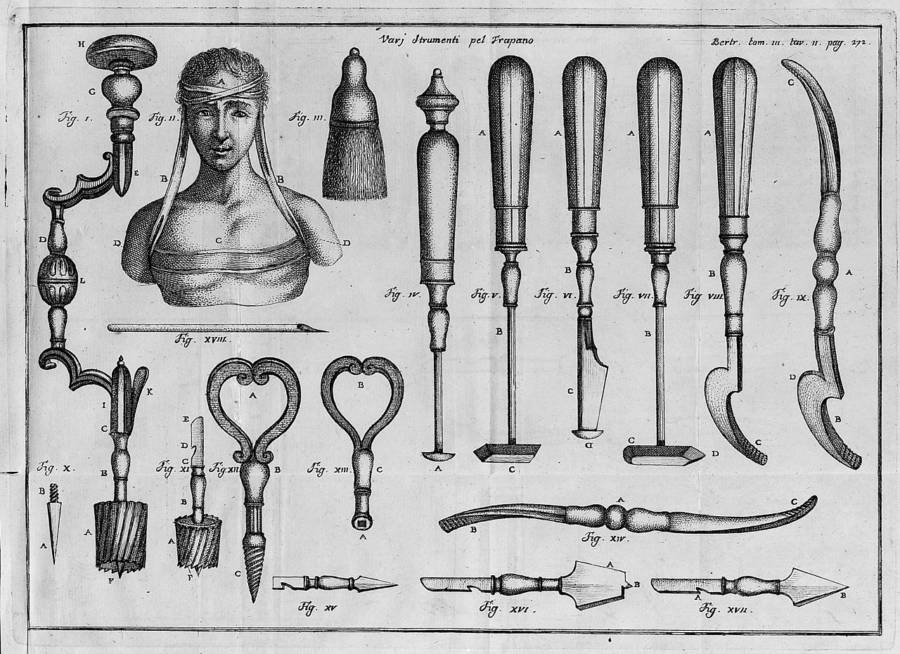

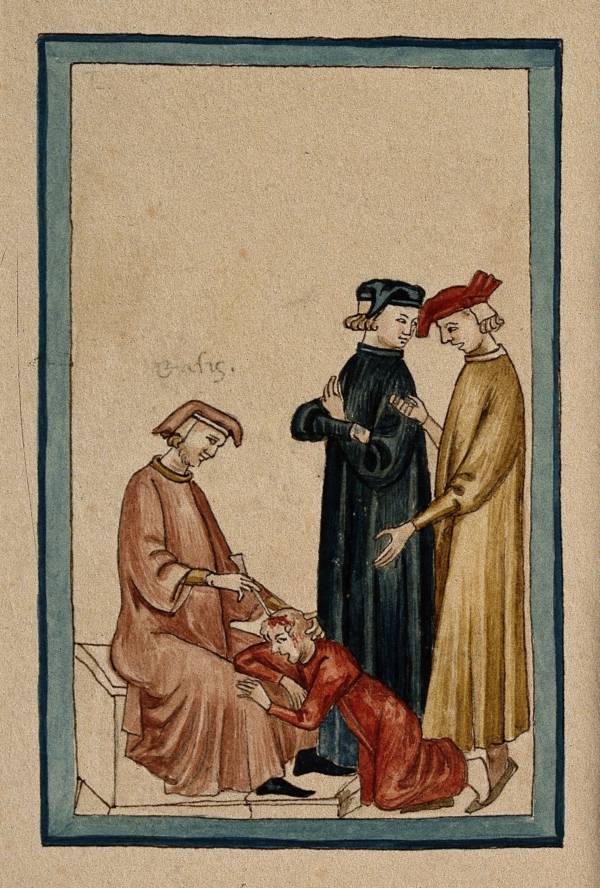

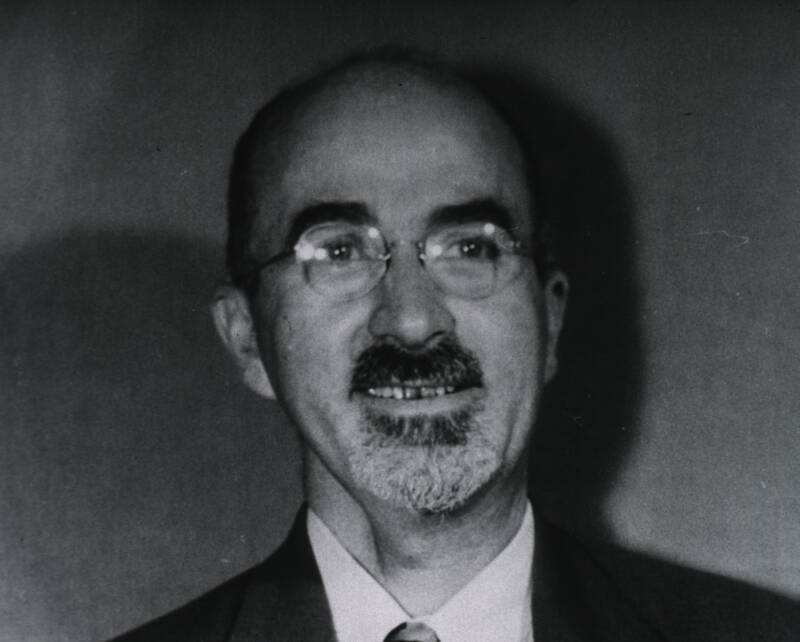

In 1935, Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz introduced a procedure called the leucotomy. It involved drilling holes in patients' skulls and injecting alcohol into their frontal lobes to destroy white matter, aiming to disrupt problematic neural pathways associated with mental illness. Moniz later began using a surgical instrument called a leucotome to cut several small, circular cores into brain matter.

Public DomainA 1932 portrait of Egas Moniz.

Walter Freeman was inspired by Moniz's procedure, but he felt that it needed to be refined. He teamed up with neurosurgeon James W. Watts and modified the operation to completely separate the connections between the frontal lobes and the thalamus rather than cutting cores. Freeman dubbed his version the "prefrontal lobotomy," and he and Watts performed the first surgery in the U.S. on Sept. 14, 1936, on a 63-year-old Kansas housewife named Alice Hood Hammatt, who suffered from depression and insomnia.

By 1942, the two doctors had carried out more than 200 lobotomies, but just 63 percent of their patients reported an improvement in their mental disorders, while 14 percent had worsening symptoms.

Their most famous case was that of Rosemary Kennedy, the sister of future U.S. President John F. Kennedy. Rosemary had started experiencing violent rages in her early 20s, and her influential family didn't want her behavior to affect their political ambitions. Her father, Joe Kennedy, brought her to meet Walter Freeman, who diagnosed her with "agitated depression" and promised that a lobotomy would calm her.

She underwent surgery in November 1941 at age 23 — and was left with the mental capacity of a two-year-old child. She was institutionalized for the rest of her life.

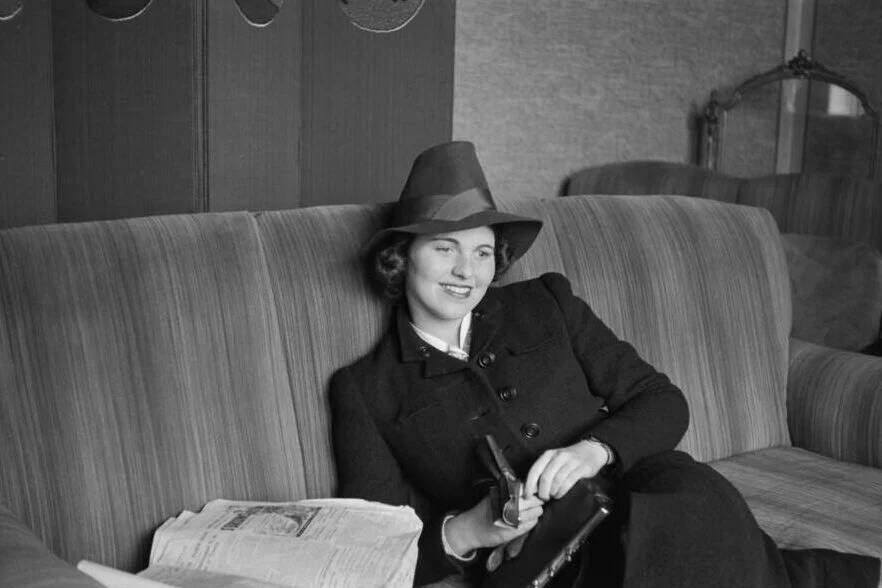

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and MuseumRosemary Kennedy, the sister of President John F. Kennedy and one of history's most infamous lobotomy patients.

By this time, Freeman was growing unsatisfied with the operation. He thought that there had to be a quicker and easier way to perform it. In fact, his ultimate goal was to make it possible for psychiatrists to carry out the procedure in their offices without an operating room or a neurosurgeon.

He soon learned of an Italian doctor named Amarro Fiamberti who operated on his patients' brains by entering through their eye sockets, eliminating the need to drill into their skulls. Freeman began experimenting with this technique, and in January 1946, he performed his first "transorbital lobotomy."

How Walter Freeman Popularized The Transorbital Lobotomy

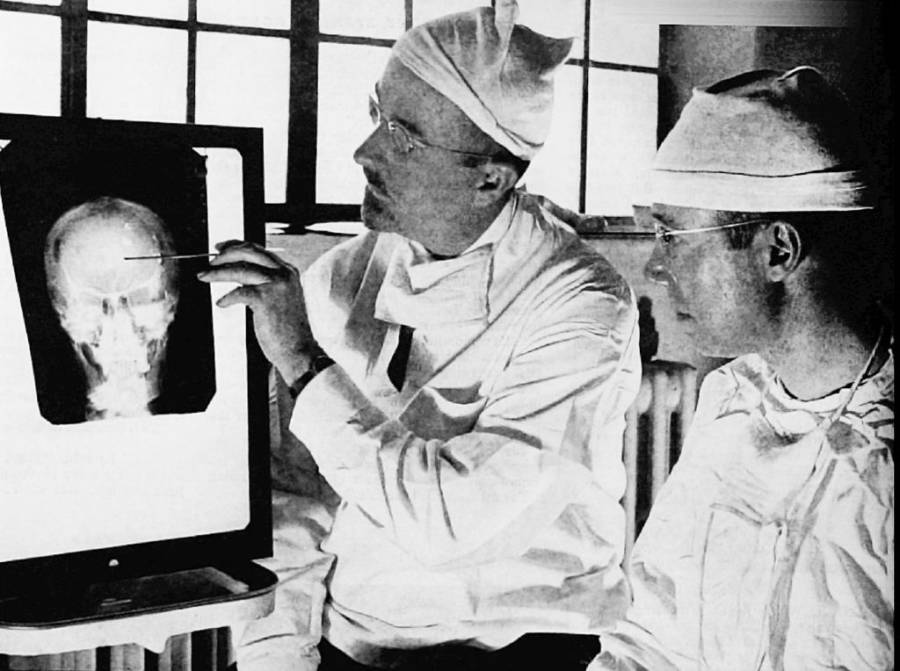

National Library of MedicineWalter Freeman's lobotomies ultimately left hundreds dead and many more injured.

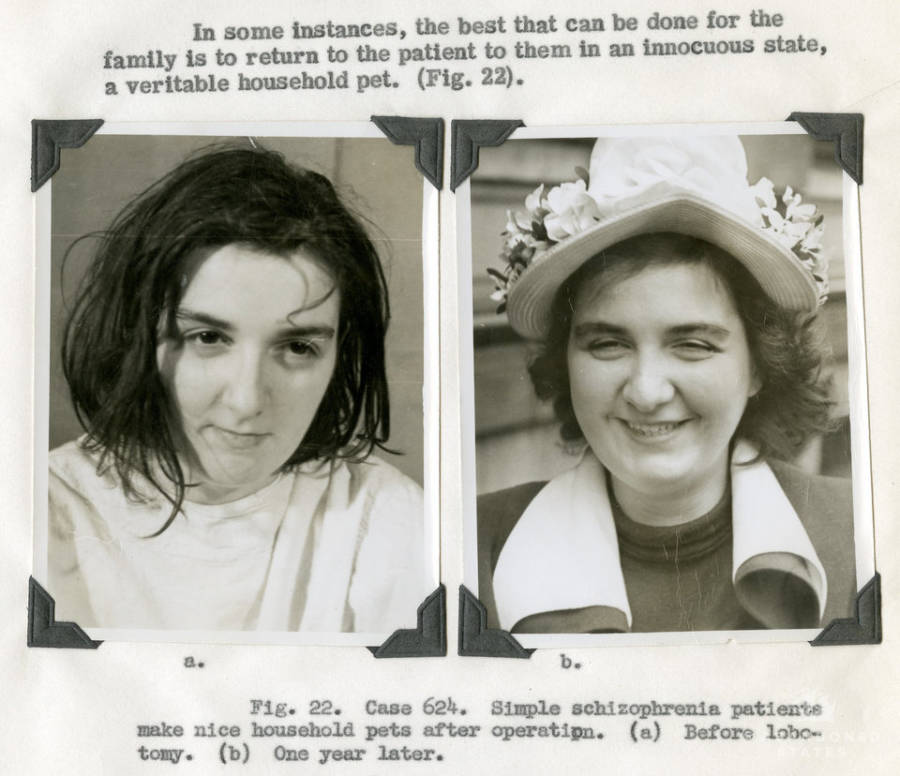

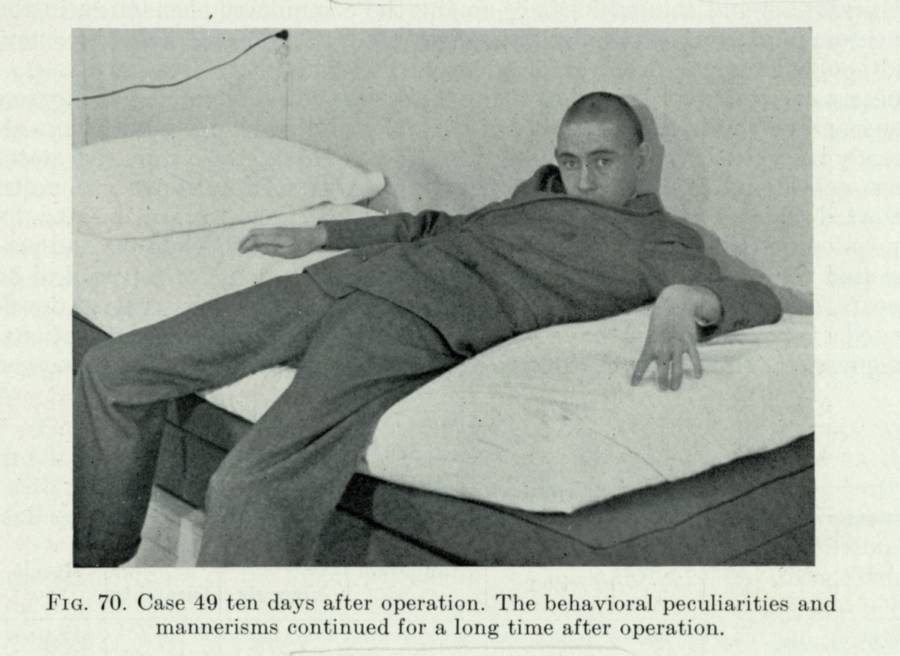

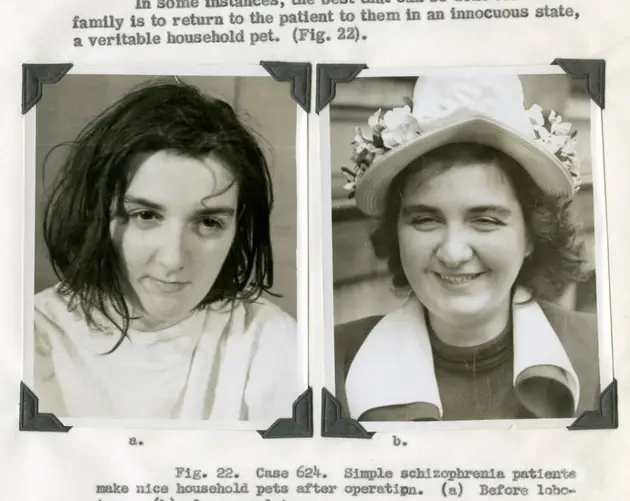

Walter Freeman's version of the transorbital lobotomy involved inserting an instrument similar to an ice pick through his patients' eye sockets, hammering through the thin orbital bone at the top of the cavity until he reached the brain, and moving the pick around to destroy the frontal lobe tissue that was believed to be responsible for mental illness.

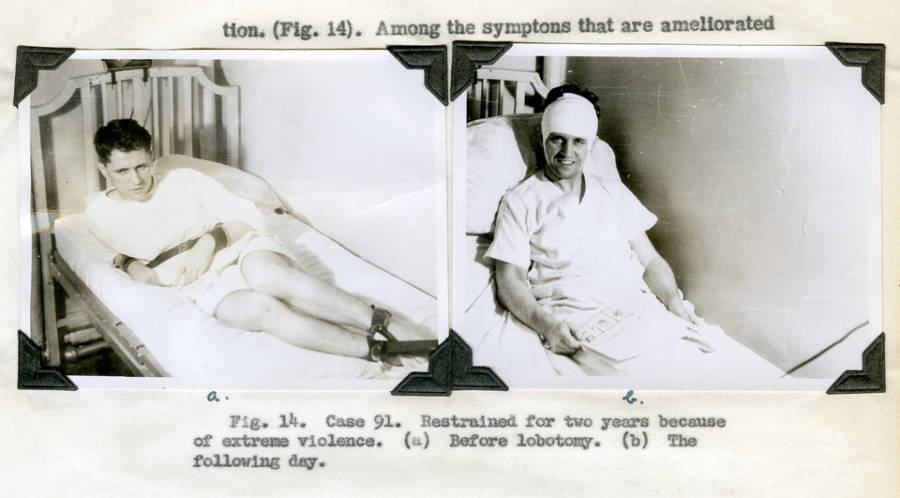

He believed that his surgery was simple enough to perform outside of operating rooms, and he embarked on a nationwide tour to demonstrate it to other medical professionals. He used the resulting media coverage to garner attention for the procedure, advertising the lobotomy as a quick fix for mental illness. Meanwhile, Watts was so disturbed by the operation that he ended his partnership with Freeman.

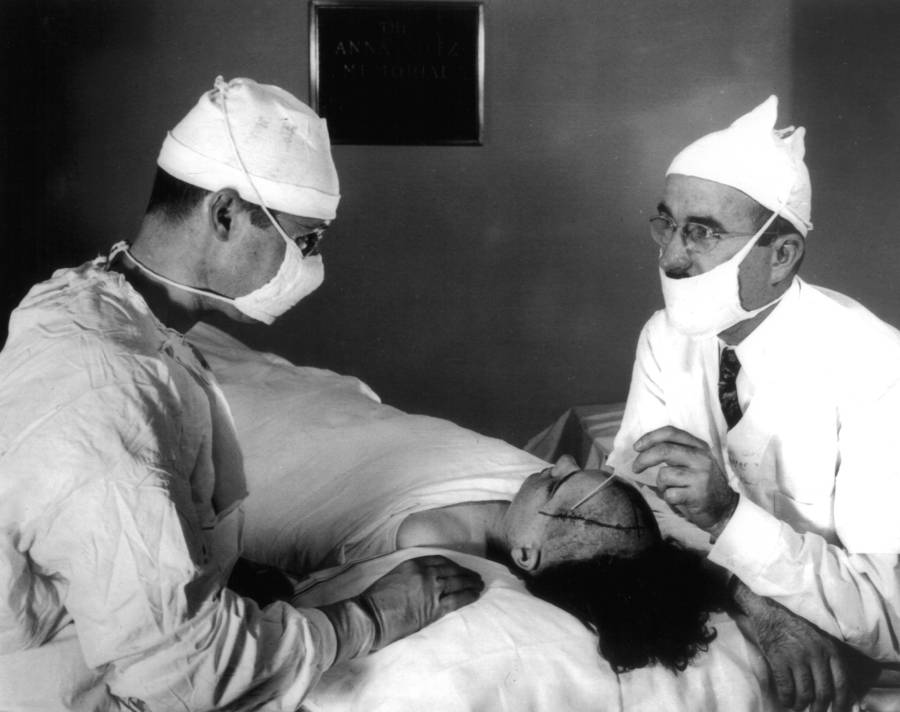

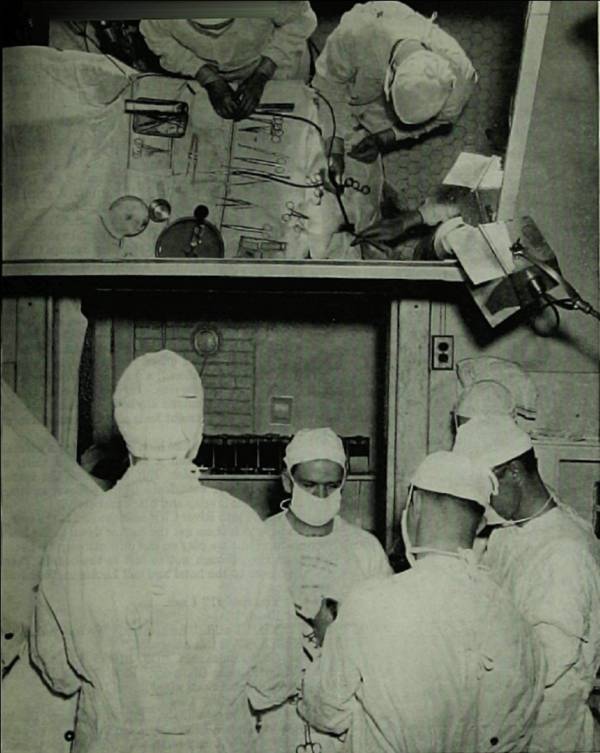

Public DomainTwo surgeons in Sweden performing a lobotomy in 1949.

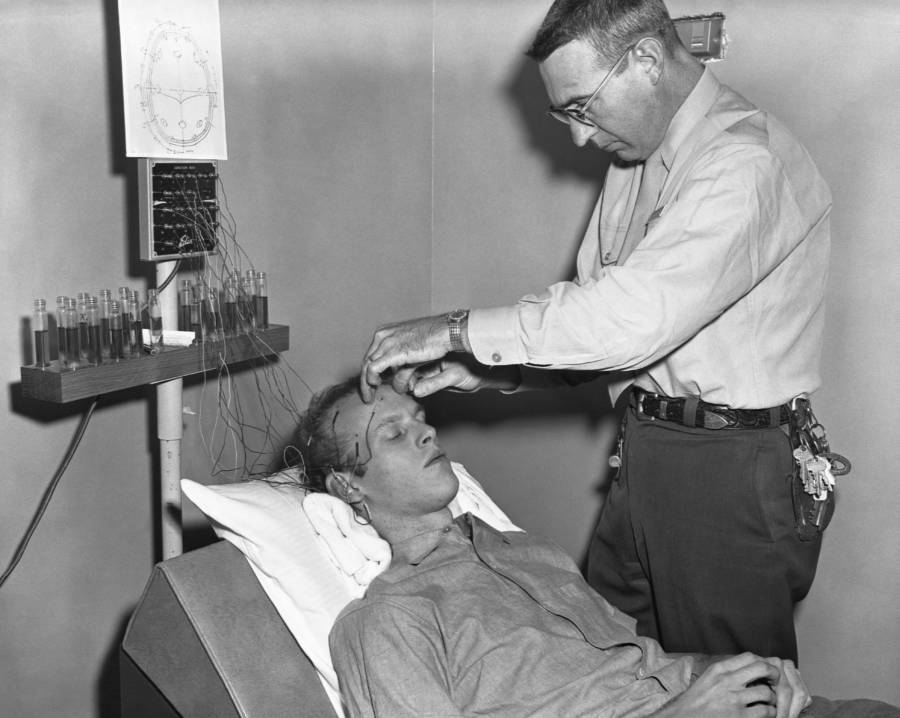

During his tour, Freeman often performed multiple lobotomies per day. According to the National Institutes of Health, he once operated on more than 50 people in three states in just four days. Notably, the doctor didn't use anesthesia for these procedures, instead applying electric shocks to induce seizures and unconsciousness in his patients.

While many people who were lobotomized did report an improvement in their symptoms, hundreds of others were left incapacitated or even dead. While Freeman was operating on a patient in 1951, he stopped during the surgery to pose for a photo and accidentally pushed his instrument too far into the man's brain, killing him. Indeed, it's estimated that some 14 percent of Freeman's patients died.

In February 1967, Walter Freeman carried out his last lobotomy on a woman named Helen Mortensen, who died from a cerebral hemorrhage. He was banned from performing the surgery again, and he soon faded into obscurity and died just five years later — but he left behind a trail of irreparably damaged patients.

The Controversial Legacy Of Walter Freeman's Lobotomies

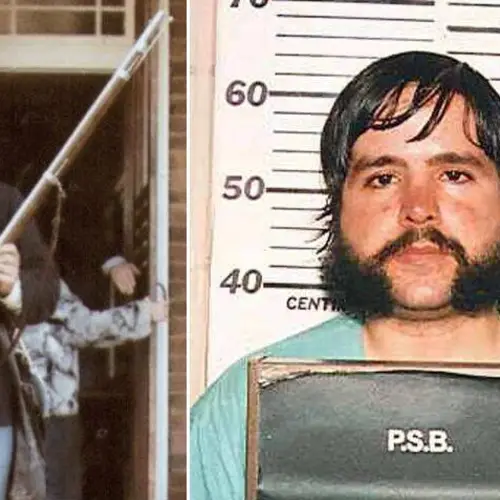

Howard Dully was just 12 years old when he received a lobotomy from Walter Freeman in December 1960. According to a 2005 report by NPR, the boy's family described him as "defiant" and "savage looking." Freeman wrote in his notes that Howard "doesn't react either to love or punishment. He objects to going to bed but then sleeps well... He turns the room's lights on when there is broad sunlight outside."

Howard thought that his stepmother simply hated him and wanted to get rid of him. Still, his father agreed to have him lobotomized, although he later claimed he was "manipulated, pure and simple" by his wife and Freeman.

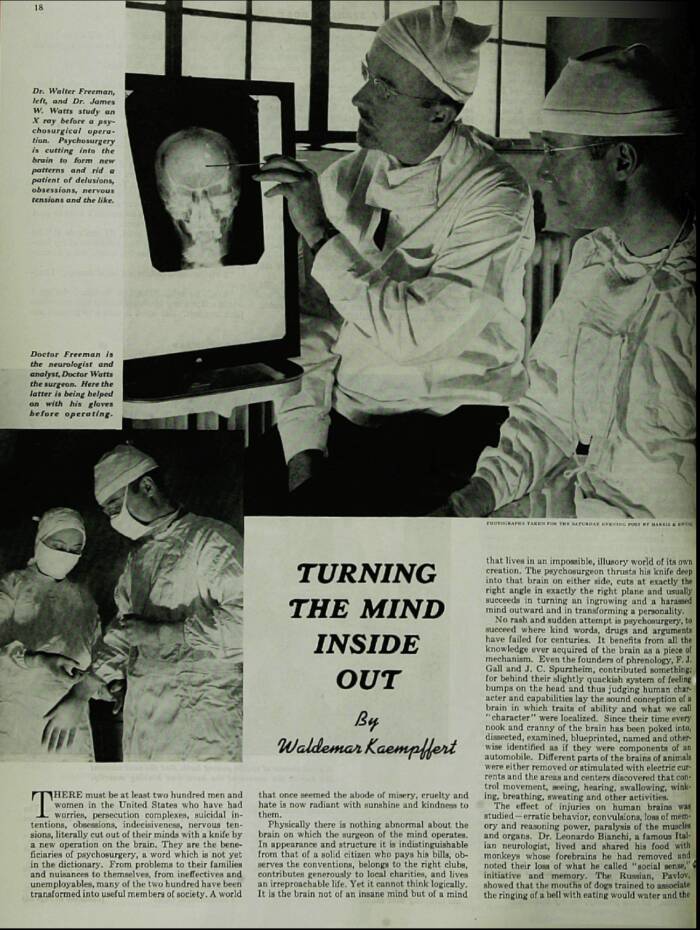

Public DomainCoverage of Walter Freeman and the lobotomy from the Saturday Evening Post in 1941.

While Howard didn't suffer catastrophic consequences from his lobotomy, he stated later in life, "I've always felt different, wondered if something's missing from my soul... I'll never know what I lost in those 10 minutes with Dr. Freeman and his ice pick."

"By some miracle it didn't turn me into a zombie, crush my spirit or kill me," Howard Dully said. "But it did affect me. Deeply. Walter Freeman's operation was supposed to relieve suffering. In my case it did just the opposite. Ever since my lobotomy I've felt like a freak, ashamed."

Thankfully, lobotomies declined in popularity alongside Freeman. The first antipsychotic and antidepressant medications were introduced in the 1950s, forever changing the treatment of mental illness.

The heyday of the lobotomy was over.

After this look at Walter Freeman and the history of the lobotomy, read up on tragic actress Frances Farmer, one of history's most infamous disputed lobotomy recipients. Then, discover five bizarre and grotesque historical "cures" for mental illness.