In April 1862, a group of Union men stealthily traveled to Georgia to steal a Confederate locomotive, but their plan ultimately failed after a seven-hour train chase.

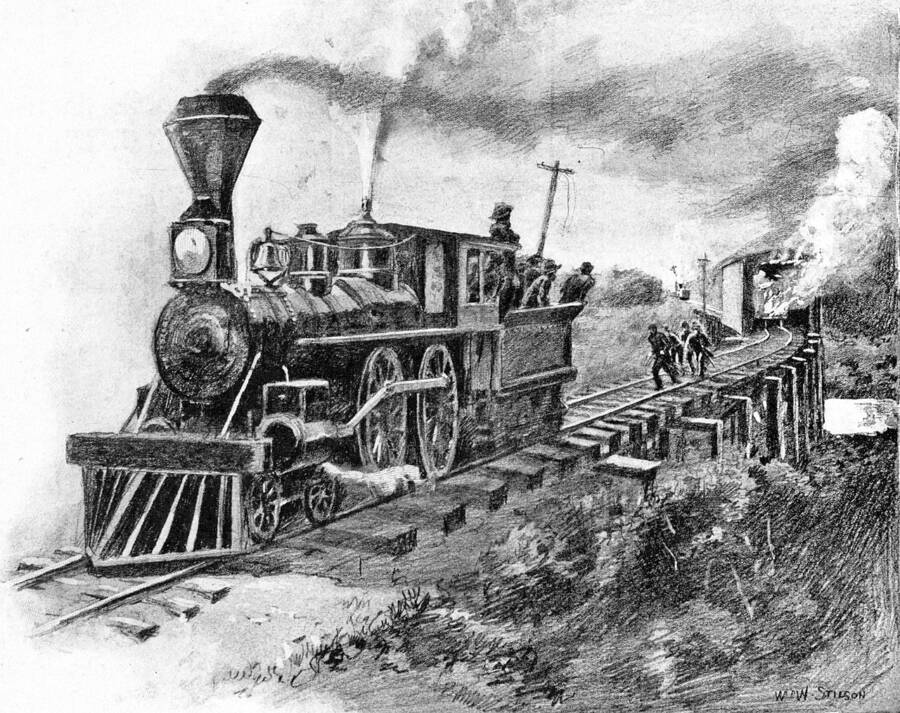

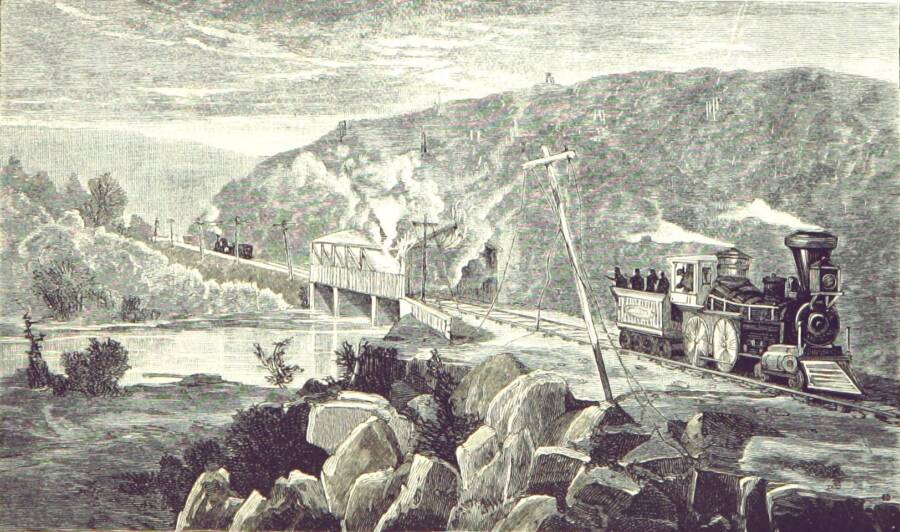

Wikimedia CommonsUnion raiders stole a Confederate locomotive, triggering a train chase that lasted for seven hours.

On April 12, 1862, train conductor William Fuller and his engineer, E. Jefferson Cain, sat down for breakfast with their locomotive, The General, within eyesight. Then, to their shock, their train began to move. The General had been commandeered by a ragtag group of Union volunteers and — with Fuller and others in pursuit — the Great Locomotive Chase began.

The plan to steal a Confederate train, hatched by a civilian spy named James J. Andrews, had a dual purpose. It was meant to destroy Western and Atlantic Railroad and cut off Confederate supplies to Chattanooga, making the city vulnerable to capture by Major General Ormsby M. Mitchel.

In the end, the Great Locomotive Chase wouldn’t go exactly to plan. But it would cement James J. Andrews’ name in history, lead to the first Medal of Honor, and inspire a number of famous films.

James J. Andrews’ Plan To Steal A Confederate Train

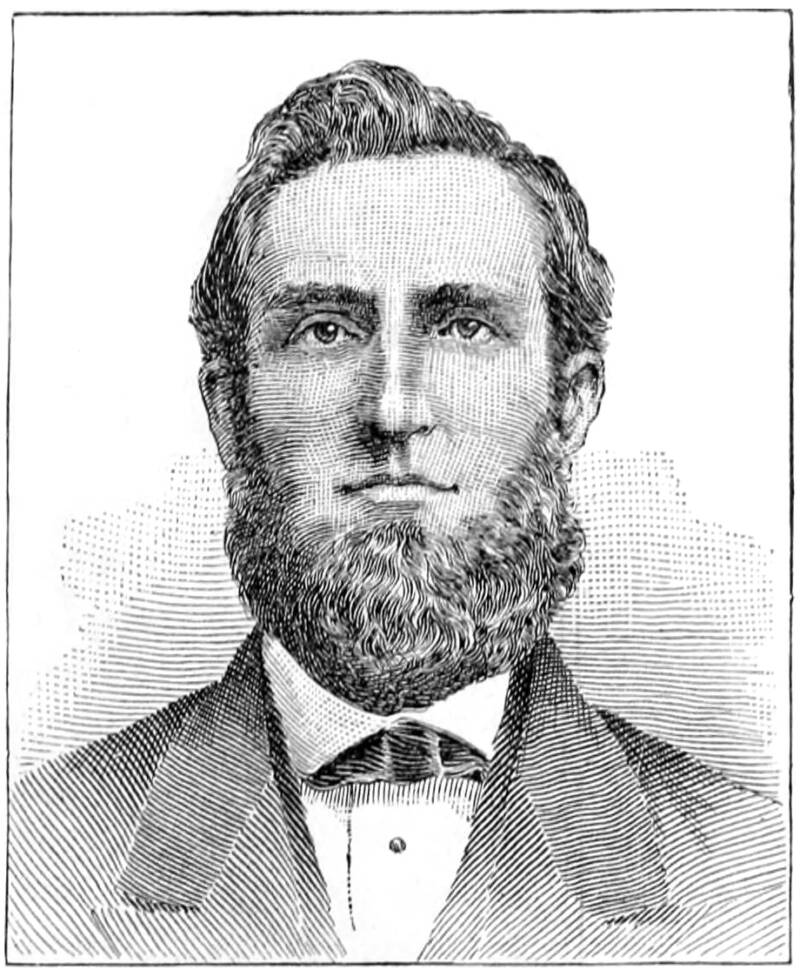

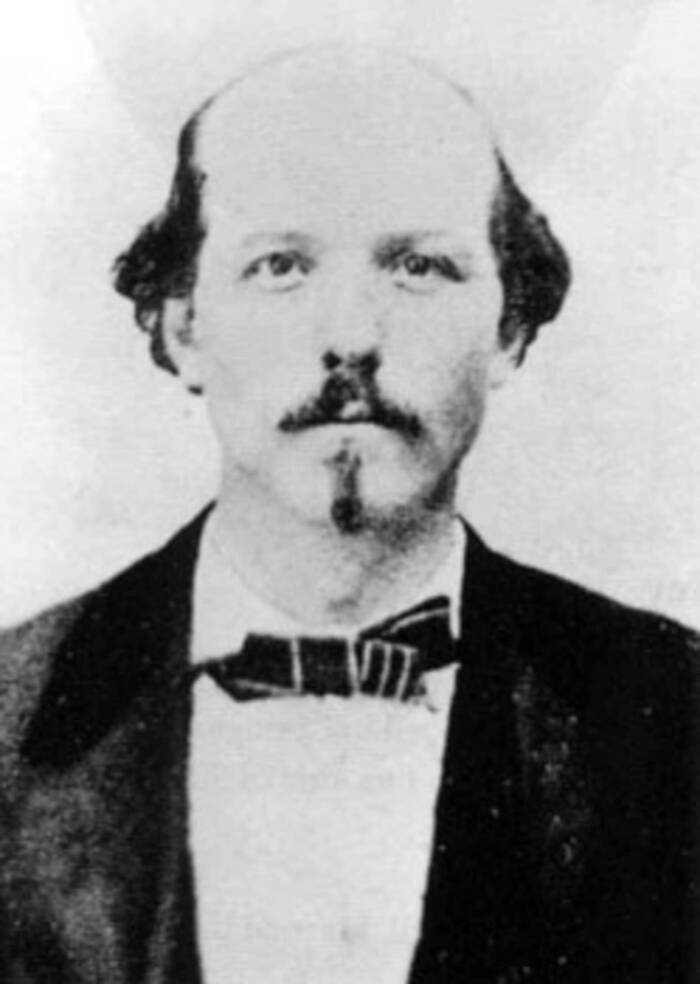

Public DomainAn engraving of James J. Andrews, the man behind Andrews’ Raid, or the Great Locomotive Chase.

The plan for the Great Locomotive Chase, also known as Andrews’ Raid, originated with a Kentucky man named James J. Andrews. A former house painter and singing coach, Andrews had started working with Union General Don Carlos Buell during the American Civil War as a smuggler, spy, and scout. And Andrews had come up with an idea to help war effort.

Determined to take the war deeper into Confederate territory, Andrews proposed an audacious idea: to sneak into the South and steal a train. Taking the locomotive back north, he and his men could destroy tracks and telegraph lines, and cut off supplies between Confederate forces.

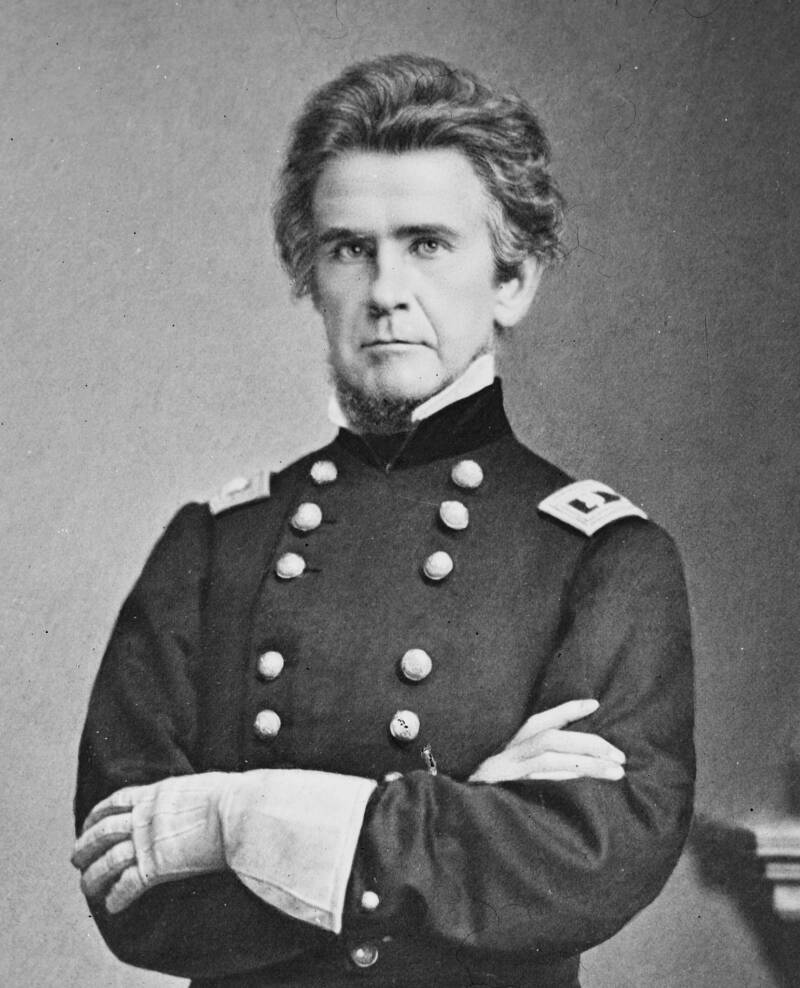

The plan appealed to Union General Ormsby Mitchel, who sought to capture the crucial Confederate city of Chattanooga, Tennessee. Andrews’ plan would cut off supplies to Chattanooga, making the city vulnerable to attack, and if Mitchel captured Chattanooga, he would also block Confederate forces in the west from the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys.

Public DomainUnion General Ormsby Mitchel approved of Andrews’ plan in early 1862, hoping that the audacious theft could help him capture Chattanooga, Tennessee.

In the spring of 1862, Mitchel gave Andrews his approval. And “Andrews’ Raid” into the Confederate South began.

By April 7, 1862, Andrews had gathered some two dozen volunteers from three Ohio infantry regiments. Dressed as civilians, they slowly made their way south. Two were captured along the way, and two overslept — but Andrews and the rest made their way to Kennesaw, Georgia, by April 12.

There, they put the Great Locomotive Chase into motion.

How The Great Locomotive Chase Began

James J. Andrews and his men targeted a train station in Kennesaw known as Big Shanty because it didn’t have a telegraph station. If everything went according to plan, the Confederates would be unable to alert others to the train theft, thus giving Andrews and his men a healthy head start.

And at first, everything did go according to plan.

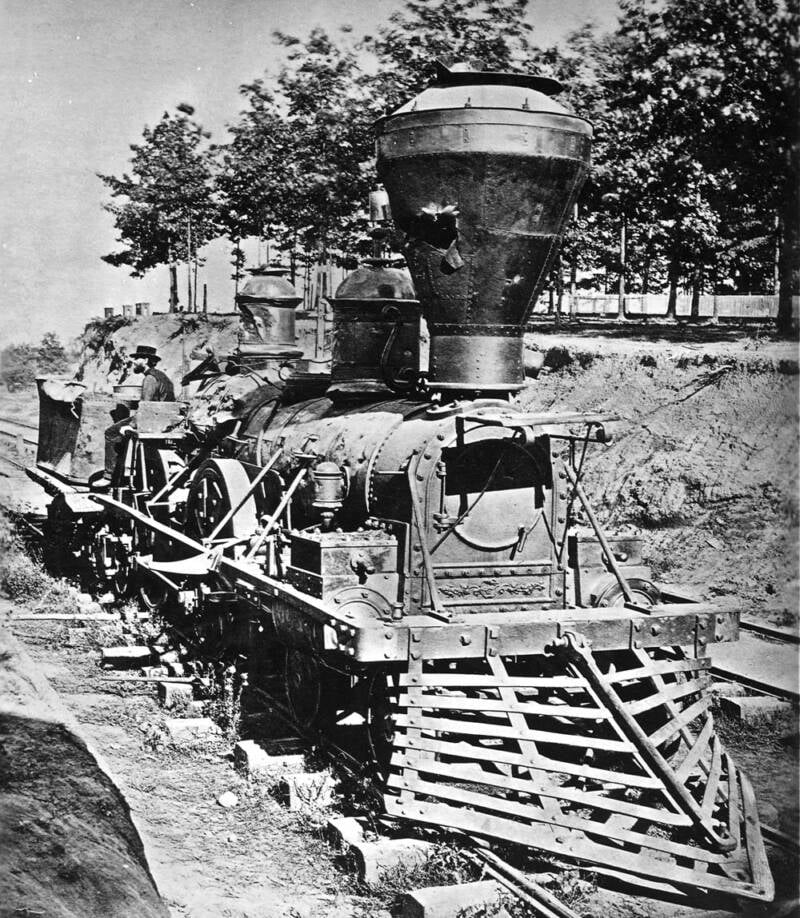

Public DomainA Confederate locomotive, possibly The General, which was stolen during the Great Locomotive Chase.

At 5:20 a.m., a train called The General pulled into Big Shanty. Its passengers and crew disembarked for a quick breakfast, and Andrews and his men put their plan into action. After separating most of the railroad cars, they climbed into The General and fired up the engines.

According to a 2015 article from the Warfare History Network, the train’s movement was noticed by Western and Atlantic Railroad foreman Anthony Murphy. Murphy shouted to William Fuller, The General’s conductor, “Someone is running off with your train!” But it was too late.

FLHC DEC1412 / Alamy Stock PhotoWilliam Allen Fuller, the conductor of The General who pursued the train during the Great Locomotive Chase.

At first, Andrews’ Raid appeared successful. The General chugged north as the raiders cut telegraph lines, lit bridges on fire, and pulled up the tracks. Though Confederates initially believed that the train had been stolen by Confederate deserters, it slowly dawned on them that The General had been commandeered by men from the North.

And Fuller was determined to recapture his locomotive. “I must follow as fast as possible,” he told himself, according to the Warfare History Network, “and try to get it back before I get very badly out of time.”

The Great Locomotive Chase was on.

The Great Locomotive Chase Runs Out Of Steam

Though Andrews and his men had the advantage of surprise, it was just about their only advantage. Fuller and other pursuers were right on their tail, and while Andrews was stuck with The General, they could change trains as needed. In all, they would use three locomotives during their pursuit.

British LibraryA depiction of the Great Locomotive Chase, in which Andrews and his men attempted to burn bridges as they fled north.

What’s more, the news that Union men had stolen a Confederate train elicited a huge Confederate response. Confederate soldiers quickly joined the Great Locomotive Chase, determined to capture the stolen train before it slipped out of their grip and crossed into Union territory.

Despite this pressure, Andrews and his men did their best to keep their pursuers one step behind. They let loose the empty boxcars, pushed The General to its limit, and tried to destroy tracks as they went. But they were unable burn a crucial bridge over the Oostanaula River, and their pursuers followed so closely that The General quickly began to run out of fuel.

With a locomotive of his own, Fuller was also able to keep up with Andrews. When he encountered parts of the track that Andrews had destroyed, he and his men ran on foot, hopped on another locomotive, and continued the chase. Though their new train was going south, Fuller simply drove the locomotive in reverse in order to keep up with Andrews and his raiders.

And seven hours later, the Great Locomotive Chase came to an end. The General had traveled nearly 90 miles, and was just 18 miles from Chattanooga — but the stolen train was out of steam. Andrews and his men were forced to abandon it just north of Ringgold, Georgia.

Though they ran into the woods, he and the others didn’t get far. They were all eventually captured.

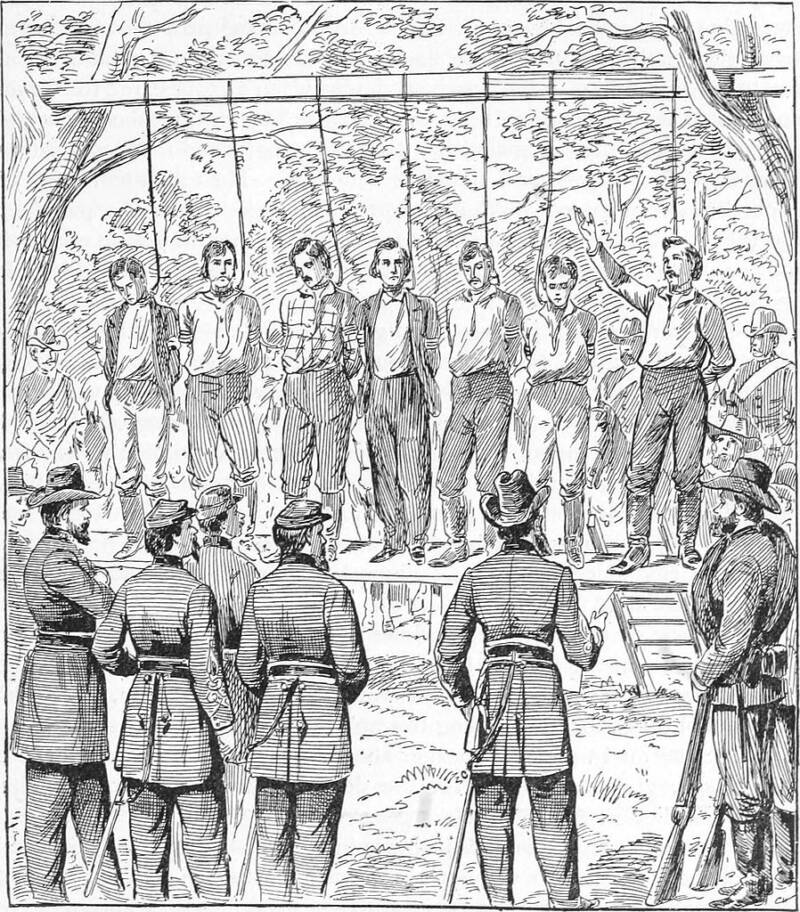

Internet Archive Book ImagesThe Confederacy executed eight of the men who carried out the raid, including civilian James J. Andrews.

The men of the Andrews’ Raid were found guilty of “acts of unlawful belligerency.” Andrews and seven others were hanged. Several others attempted to escape, but only eight of them succeeded — the others became POWs.

The Legacy Of The Great Locomotive Chase, From The First Medal Of Honor To Hollywood

The Andrews Raid ultimately failed. Although they’d successfully stolen a locomotive, Confederates quickly replaced the cut telegraph lines and missing tracks, and Mitchel did not move to capture Chattanooga.

But the train hijacking became a sensation in the North, where the raiders were celebrated as heroes. In the spring of 1863, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton awarded the newly created Medal of Honor to the six survivors.

Library of CongressA monument to the Andrews Raid in Chattanooga, Tennessee contains a replica of The General.

Private Jacob Wilson Parrott recieved the first Medal of Honor because he endured beatings more than 100 times as a POW and never gave up information on the raid. Because only soldiers could receive the Medal of Honor, however, James J. Andrews, a civilian, never received one.

But his audacious plan was not forgotten. The thrilling chase inspired Hollywood, and led to the films The Great Train Robbery in 1903, Railroad Raiders of ’62 in 1911, Buster Keaton’s The General in 1927, and, famously, the Disney movie The Great Locomotive Chase in 1956.

As such, though Andrews’ Raid was a failure, the Great Locomotive Chase lives on as one of the most audacious moments in the Civil War.

The Andrews Raiders were the first to receive the Medal of Honor but not the last. Next, learn about Mary Edwards Walker, the first female surgeon in the Army and the only woman to win the Medal of Honor. Then read about the St. Albans Raid, a Confederate scheme to rob banks in Vermont.