In 1821, Gregor MacGregor made a fortune off of European elites by selling them shares in his fake utopia — then got off scot-free.

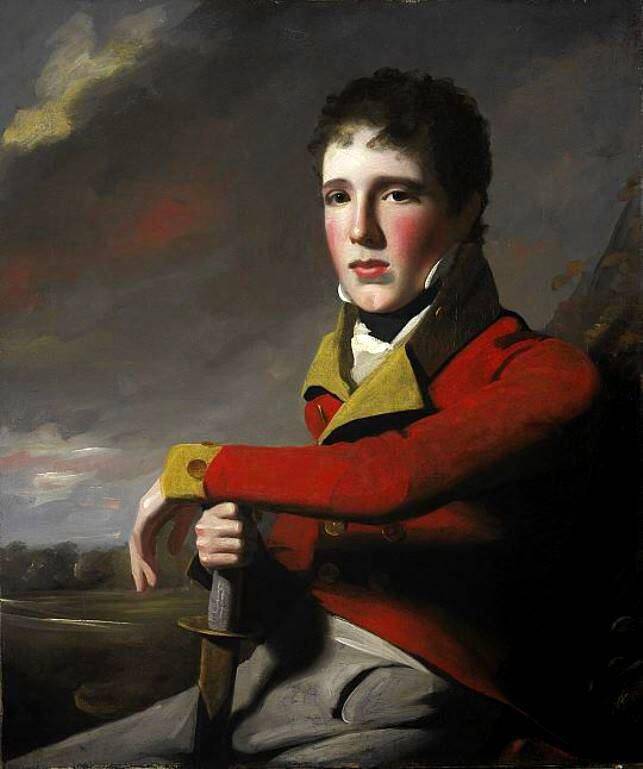

National Portrait GalleryGregor MacGregor, Prince of his fabricated kingdom of Poyais.

As Europe raced to conquer vast tracts of undiscovered land in the Americas, a Scottish conman named Gregor MacGregor hatched a plan to capitalize on the lucrative colonization game.

In 1821, MacGregor fabricated a colony called Poyais on the Bay of Honduras in Central America and scammed the British into investing in it. He even convinced 200 people to move there, who were then all forced to evacuate when they realized that Poyais was not the utopia MacGregor had made it out to be.

This is the absurd true story of how a Scotsman convinced the West that he had founded an idyllic colony — and got away with it.

The Early Schemes Of Gregor MacGregor

Born and raised in a wealthy Scottish family, Gregor MacGregor did not seem like the type to become a conman.

At the age of 16, MacGregor joined the British Army after his family purchased him a commission. He was briefly deployed in the Napoleonic Wars, during which time the Scottish elitist bought himself the rank of Colonel for about $1,000. He also met and married Maria Bowater, who was of an influential British family.

National Gallery of ScotlandGregor MacGregor in the British Military, as portrayed by George Watson in 1804.

In 1810, however, MacGregor was disgraced from the British Army following a dispute and his wife died. Now finding himself in financial straits without her family’s patronage, MacGregor attempted to establish himself as an aristocrat in London by falsely referring to himself as Scottish royalty and adopting the title of “Sir.” When the British elite largely ignored him, MacGregor opted instead to explore the New World.

Thus, in 1812, he sold his Scottish estate, sailed to Venezuela, and there “Sir” Gregor was warmly received by General Francisco de Miranda, one of the country’s revolutionaries and colleague of famed Venezuelan political revolutionary Simon Bolívar.

MacGregor enjoyed several years of successful military service under Bolívar, who was leading wars of independence across the Americas as natives struggled to beat back imperializing Spaniards.

After victories in multiple confrontations, from daring defense plans to several lucky escapes, Sir Gregor won sizable acclaim for his courage and leadership.

As an integral part of Bolívar’s secession movement from the Spanish Empire, MacGregor rose all the way to General of Division in the Army of Venezuela. He even married Josefa Lovera, Bolívar’s cousin. And yet amid this period of success, a 25-year old MacGregor saw an even better chance for fame and fortune.

Inventing The Fake Paradise Of Poyais

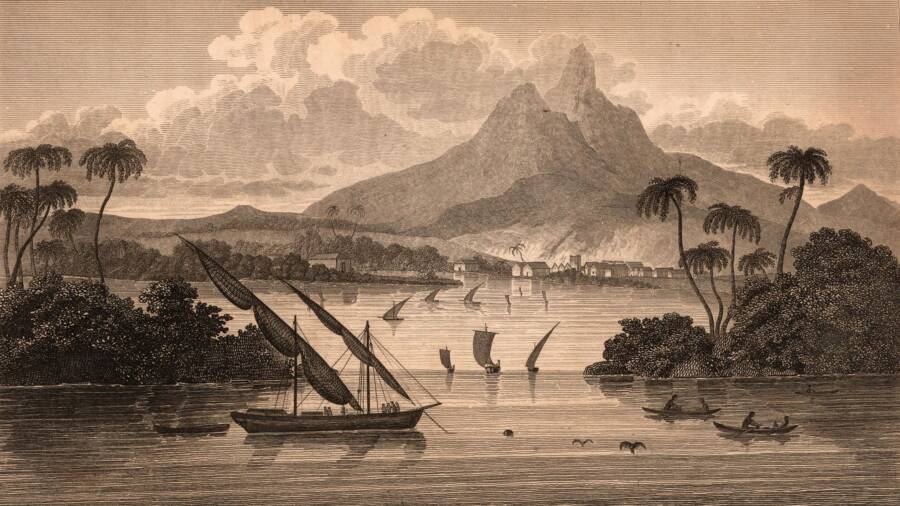

Wikimedia CommonsAn illustration of Poyais, the fake country that MacGregor invented, in his “official” guidebook.

In 1820, MacGregor stumbled upon a desolate, pest-ridden piece of land on the inhospitable coast of Nicaragua. The territory was controlled by the Miskito People, a tribe descended from Indigenous Native Americans and shipwrecked African slaves.

The inhabitants, seeing no real use for the land that MacGregor was interested in, ceded a swath of it the size of Wales in exchange for rum and jewelry. MacGregor promptly dubbed the land “Poyais” and named himself the royal leader of it.

When he returned to London in 1821, MacGregor began spreading the word of his new, idyllic colony. As a wartime hero with an engaging personality, people listened eagerly to his stories, and especially those of Poyais, which he claimed was a utopia.

The natives were not only friendly, MacGregor asserted, but also loved the British. The soil was not just fertile but it was also complemented by year-round temperate conditions, beautiful natural landscapes, and vast herds on countrywide prairies.

The country was not only settled, he gushed, but it already had a capital city with domes and colonnades of state buildings. Governance was great, MacGregor claimed, with mechanisms like a tricameral parliament, banking systems, and land titles all in place already.

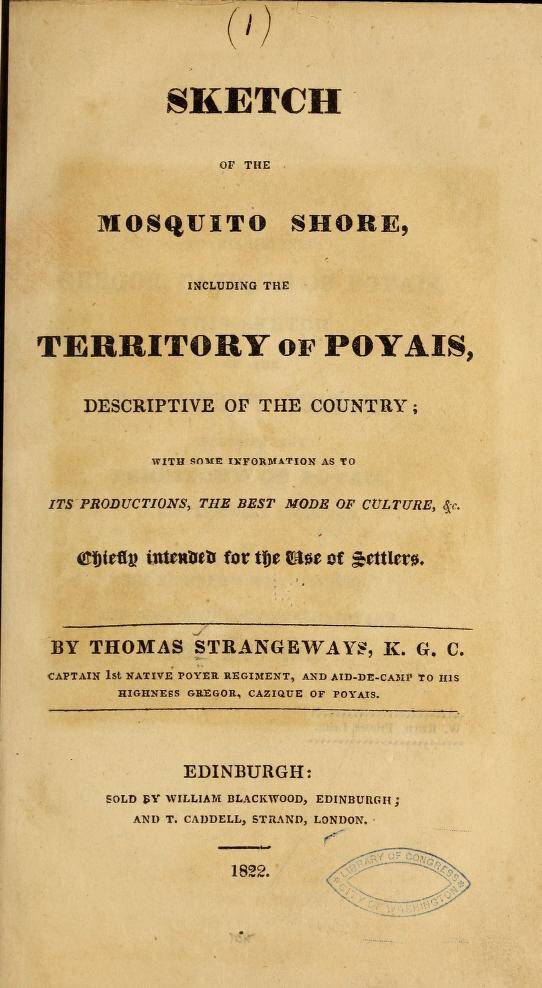

MacGregor worked hard to make his story credible. He manufactured huge amounts of official-looking documents and rapidly pushed the message of Poyais into the printed word. He even fabricated a 355-page guidebook of the fake colony called Sketch of the Mosquito Shore by a fictitious explorer named “Captain Thomas Strangeways.”

The manual was filled with detailed information, drawings, and engravings, and was printed and sold in the thousands across London and Edinburgh. Poyais was incorporated into maps, and books furnished tales of the mythical country.

Library of CongressThe Poyais “guidebook,” by Captain Thomas Strangeways.

MacGregor had also picked an opportune moment in European history to pull his scheme. In the early 1800s, inaccurate cartography and constantly-changing South American borders were rampant, so who was to say that Poyais didn’t exist?

Britain Invests In Poyais

With the support of publicity, MacGregor opened offices in London and Edinburgh to sell land in Poyais at two shillings per acre, and demand immediately went through the roof.

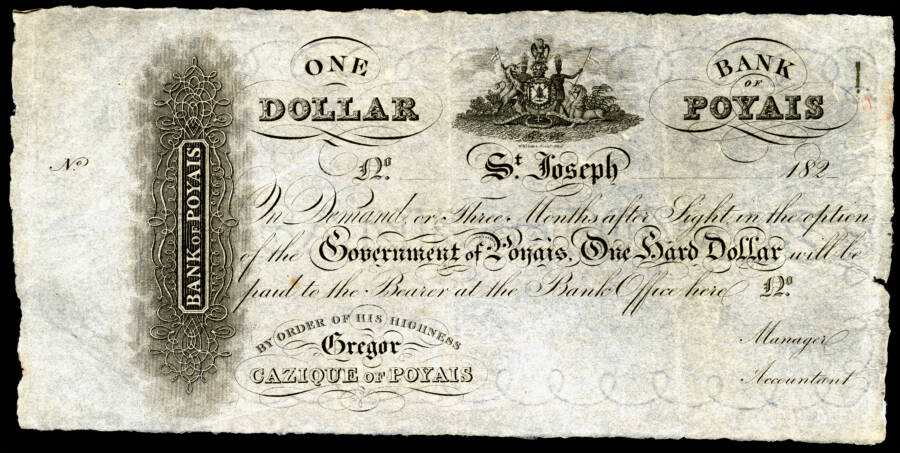

As people lined up to invest in the new land, MacGregor raised the price to four shillings per acre and then six. Alongside land, MacGregor even organized the listing of a Poyaisian loan on the London Stock Exchange and sold fake currency from the Bank of Poyais to everyday citizens. The money was printed by the Bank of Scotland’s official press. He even told hopeful settlers that they could exchange their pounds sterling for Poyais dollars.

National Museum of American History at the SmithsonianPoyais currency, printed by the Bank of Scotland.

Next, MacGregor embarked on his ultimate, and final, deception. He organized and chartered two voyages of settlers to Poyais. In September and October of 1822, over 200 hopeful settlers set sail on two ships to nowhere.

The travelers, of course, were rather bemused when they arrived at the purported location of Poyais. They found nothing but uninhabited swampland and virgin forest. The new immigrants, so sold on the story, believed that they had simply made a sailing error and began unloading their supplies. Poyais, in their minds, was nearby. They decided simply to dock and venture inland to find it.

Alas, there was nothing there. While the settlers had ample supplies and provisions, their inopportune arrival in the middle of the country’s rainy season quickly caused a surge in malaria and yellow fever.

By the time help came from another British settlement 500 miles north, nearly two-thirds of the settlers had died. The remaining 50 or so made their way back to England.

Gregor MacGregor Gets Off Scot-Free

Wikimedia CommonsThe HMS Thetis, a boat like the ones that ferried MacGregor’s unfortunate investors to their doom.

When the survivors finally arrived home in 1823, MacGregor had already fled to Paris — where he was running a similar scam. This time, managed to raise almost $400,000.

In 1825, Gregor MacGregor was finally arrested and charged with fraud. His trial was held in France and was hampered by diplomatic confusion. It took over a year for it to even get going. The Scotsman, pulling off one final masterstroke, managed to redirect blame on his “associates” and was acquitted of all charges.

In the 1830s, after the hubbub surrounding Poyais had died down, MacGregor attempted a few more (largely unsuccessful) securities schemes. But after his wife died in 1838, he returned to Venezuela and settled in Caracas where he reconnected with his former military comrades.

National Art GalleryCaracas, the capital of Venezuela, as portrayed by Joseph Thomas in 1839.

With their help, MacGregor was reinstated to his former army position, and he even received back-pay and a pension. After he was confirmed as a Venezuelan citizen, he lived comfortably in the capital and was buried with full military honors when he died in 1845.

Despite his serial cheating at the expense of the money and lives of others, Gregor MacGregor’s reputation — at least while he lived — never quite faltered.

Today, he is known as the conman behind one of the most profitable lies ever, which he expertly orchestrated to perfection for decades.

After this look at the lucrative lies of Gregor MacGregor, learn about James Amistead Lafayette, the slave and double agent during the American Revolution. Then, discover the $24 million McDonalds Monopoly scam.