Hedy Lamarr was known in Hollywood as "the most beautiful woman in the world," and she also invented the technology that ultimately led to WiFi.

A stunning Austrian-born actress, Hedy Lamarr dropped jaws wherever she went and took Old Hollywood by storm. But Lamarr was more than just the “most beautiful girl in the world,” as one film director raved.

Beneath Lamarr’s jet-black bob was a mind of science. Curious, questioning, and insightful, the actress used her oft-ignored intelligence to dream up new technology. In fact, she’s even been credited as the “Mother of WiFi.”

Public DomainHedy Lamarr became famous for her acting, but that was far from her only talent.

This is the story of Hedy Lamarr, the Hollywood sex symbol whose dramatic life nearly obscured her needle-sharp intelligence.

The Early Years Of Hedy Lamarr

Donaldson Collection/Getty ImagesHedy Lamarr in the 1933 film Ekstase, or Ecstasy, where she appeared nude.

Born Hedwig Kiesler on November 9, 1914, Hedy Lamarr spent her early years in Vienna, Austria, as the glamorous belle époque faded into the bloody years of World War I. The daughter of a successful banker father and a concert pianist mother, Lamarr showed high intelligence from a young age.

Encouraged by her father Emil, who often talked to his only child about the inner workings of machines, such as the printing press, Lamarr took apart her music box at the age of five just to see how it worked. She also had an ear for language and could speak four languages by the age of 10.

But the first thing most people noticed about Hedy Lamarr was her good looks. At 16, she caught the eye of film director Max Reinhardt, who raved that her beauty was unparalleled in Europe — and maybe even the world.

From there, Lamarr’s life took a turn. Instead of taking apart more music boxes, she studied acting in Reinhardt’s Berlin-based drama school and won a role in a 1930 film called Geld auf der Straβe (“Money on the Street”).

This modest early success led to a 1933 film that would shock the world — Ekstase, or Ecstasy. In the movie, 18-year-old Hedy Lamarr played the controversial character of Eva, a new bride disappointed by her husband’s lack of sexual appetite. In a series of scandalous scenes that show Lamarr in the nude and portraying an orgasm, Eva falls into the arms of her lover.

According to the New York Times, “Pope Pius XI denounced it, but Mussolini issued a permit so that it could be shown at the Venice Film Festival. It won no awards there but attracted attentive audiences, most of them men.”

Contemporary reviews called the film “indecent and morally dangerous,” “unsuitable, immoral, and lascivious,” and “extremely audacious.” By the time it was shown in the United States seven years later, it appeared in only a handful of theaters and without the approval of the moralistic Hays Code.

For better or for worse, Hedy Lamarr would soon become known as the “Ecstasy Girl.” But her arc toward stardom was just beginning.

From Bored Housewife To Hollywood Star

Public DomainHedy Lamarr, far right, in a publicity still for Algiers (1938).

As Hedy Lamarr’s momentum began to build, she caught the eye of another up-and-coming Austrian: Friedrich Mandl, an arms dealer. After seeing Lamarr in the play Sissy, Mandl wooed her and the pair married in 1933.

But Lamarr — much like her character Eva — found herself trapped in an unhappy and unsatisfying marriage. Mandl forbade Lamarr from acting, tried to destroy every existing copy of Ecstasy, and relegated his bright and talented wife to the role of a hostess who entertained his friends.

“I was like a doll,” Lamarr remembered, calling Mandl a “monarch” in their marriage. “I was like a thing, some object of art which had to be guarded — and imprisoned — having no mind, no life of its own.”

Tired of spending her nights catering to Mandl and his friends — many of whom were Nazis, to the chagrin of the Jewish-born actress — Lamarr plotted her escape. In 1937, she fled her marriage and moved to London.

There, she fatefully crossed paths with Louis B. Mayer, who’d co-founded Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios (MGM) in 1924. Though Mayer had his doubts about the “Ecstasy Girl,” Lamarr slyly booked a ticket on the same ship as him and managed to change his mind during their transatlantic crossing.

Silver Screen Collection/Getty ImagesHedy Lamarr, pictured during the Golden Age of Hollywood.

She emerged from the voyage transformed. No longer was the young actress Hedwig Kiesler. She would now be known as Hedy Lamarr — a name that was an homage to the silent film star Barbara La Marr. (It was also Mayer’s best attempt to distance his new actress from her scandalous past.)

Lamarr instantly made a big splash in Hollywood. After the success of her first American film Algiers (1938), Lamarr starred in Lady of the Tropics (1939), Boom Town (1940) — in which she appeared alongside Clark Gable and Spencer Tracey — White Cargo (1942), and Samson and Delilah (1949).

But Lamarr had never forgotten the joys of dissecting a music box. “The brains of people are more interesting than the looks, I think,” she mused.

And as storm clouds gathered in Europe, Hedy Lamarr began to think of how she could use her mind — and not her body — to help during World War II.

How The Mind Of Hedy Lamarr Went To Work

Wikimedia CommonsHedy Lamarr filed a patent for technology that would pave the way for WiFi, but the U.S. military did not use it.

Hedy Lamarr kept her curiosity alive in Hollywood. An actress by day, she made small inventions by night, including a new kind of traffic light and a fizzy tablet to make soda. And when Lamarr dated the innovative businessman Howard Hughes, she took a deep dive into these interests.

Unlike other men in Hollywood, Hughes was supportive of her hobbies and once even called her a “genius.” And her greatest invention came in 1940.

Then, during a dinner party, Lamarr struck up a conversation with inventor George Antheil about the war spreading in Europe. “Hedy said that she did not feel very comfortable, sitting there in Hollywood and making lots of money when things were in such a state,” Antheil remembered.

As Lamarr thought back to the boring dinners she’d hosted with her ex-husband Mandl and his Nazi friends, she and Antheil began to tinker with an idea. They came up with something called “frequency hopping.”

Frequency hopping involved changing the frequency between a plane and a guided torpedo so that the enemy couldn’t jam the radio signals. Because the signals kept changing, they would be impossible to predict.

Though Lamarr and Antheil earned a patent for their invention in 1942, the U.S. Navy decided not to adopt frequency hopping. Lamarr ended up lending her celebrity power, and not her genius, to support the war effort.

But luckily, Hedy Lamarr’s hard work didn’t completely go to waste. The bones of her idea would later be used to develop modern-day WiFi, Bluetooth, and GPS technologies. And Lamarr would one day be recognized as the “Mother of WiFi” — but that didn’t happen for decades.

Hedy Lamarr’s Later Life And Legacy

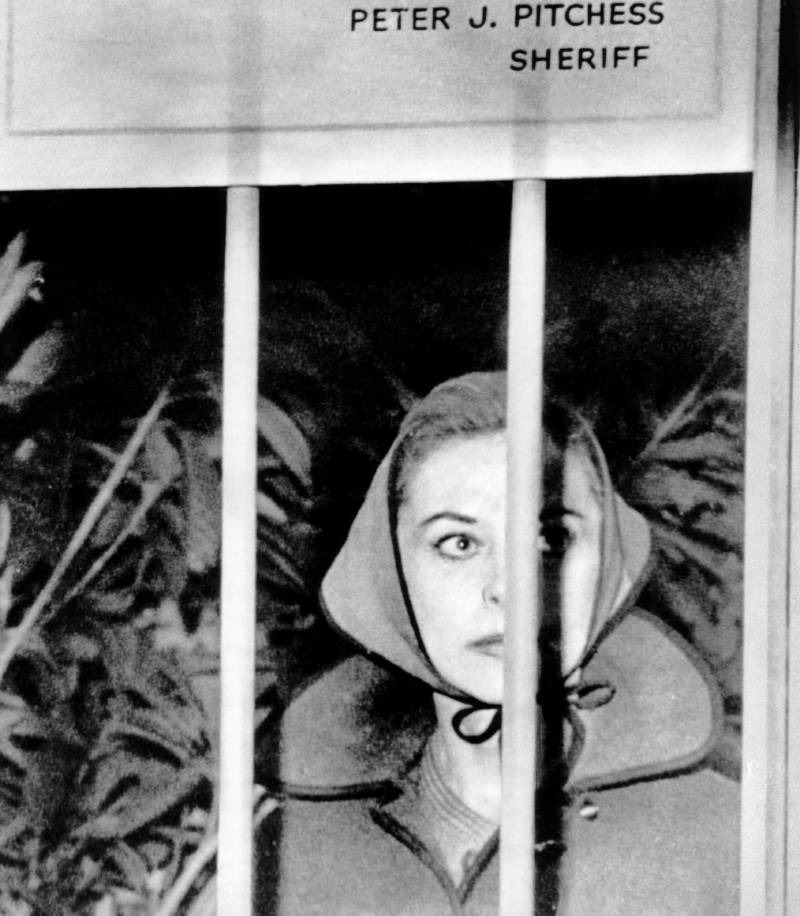

Everett Collection/PBS.orgHedy Lamarr leaving the Sybil Brand Institution for Women on bail after being arrested for shoplifting in 1966.

Sadly, the brilliance of Hedy Lamarr’s mind was frequently diminished by her personal drama. Her six marriages provided plenty of tabloid fodder, as did her controversial autobiography, Ecstasy and Me. And her arrests for shoplifting in 1966 and 1991 would put her in the spotlight yet again.

By the time Lamarr died in her Florida home in 2000, she had a strained relationship with her legacy as a famous screen siren. Her beautiful face, she wrote, “brought me tragedy and heartache for five decades. My face is a mask I cannot remove: I must always live with it. I curse it.”

Many details about her final years remain a mystery, as she infamously became a recluse in Casselberry, Florida, and rarely ventured out into public. What is known is that she died on January 19, 2000, at age 85. Hedy Lamarr’s cause of death was later revealed to have been heart disease.

But even though Hedy Lamarr’s star faded before her death, her genius mind and the causes that she was so passionate about were never forgotten. In the 1960s, her frequency-hopping technology was applied during the Cuban Missile Crisis. In later decades, it irrevocably changed the world by birthing technology that we depend on today, like WiFi and Bluetooth.

And as time marched on, Lamarr was finally seen for who she was. In 1997, the Electronic Frontier Foundation awarded Lamarr and Antheil their Pioneer Award. That same year, the “Oscars of Inventing,” the Invention Convention, awarded her the BULBIE Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award. And in 2014, Lamarr was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Throughout her life, Hedy Lamarr had played many roles. But one role captured her in a prescient way, even though it was likely by accident.

In the 1941 movie Ziegfeld Girl, Lamarr portrays a glamorous woman who wears a shimmering headdress of stars. But as dazzling as they are, their shine can’t compare to the mind of the woman herself.

After reading about Hedy Lamarr, check out these vintage photos that capture Old Hollywood in its heyday. Then, take a look at some of the most shocking Old Hollywood scandals that reveal Tinseltown’s ugly side.