The swastika was a sacred icon of spirituality around the world. Then Heinrich Schliemann came along to usher the symbol toward its Nazi destiny.

Wikimedia CommonsHeinrich Schliemann

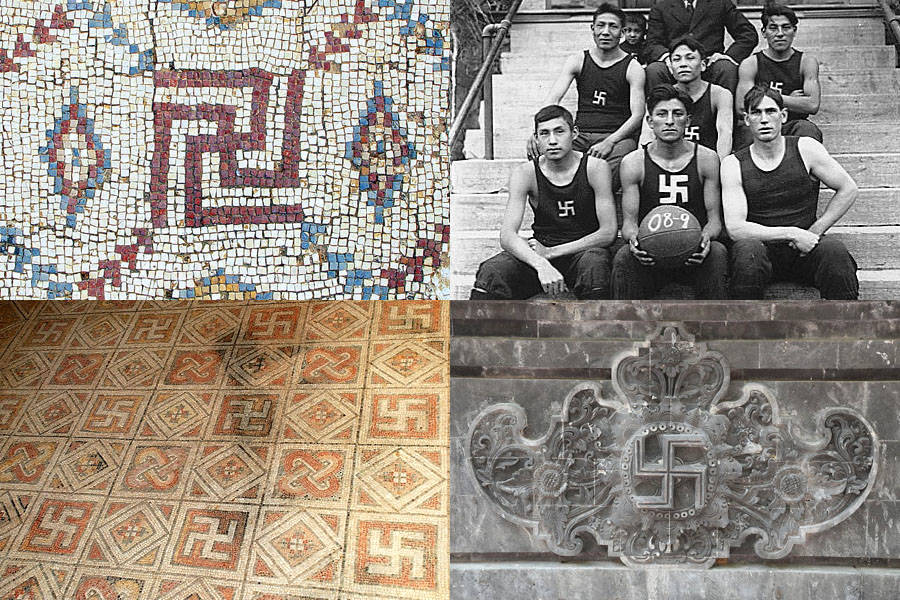

The swastika remains one of the most recognizable and emotionally-charged symbols in history due of course to its use by the Nazis. But for countless Hindus in India (not to mention other cultures around the world) the symbol has proudly adorned their temples and the statues of their deities for millennia.

They use the swastika as a symbol of prosperity and good fortune (even the Sanskrit word “swastika” itself means “conducive to wellbeing”). It’s a symbol that dates back some 12,000 years and one they still use today.

But in the space of just 25 years, the Nazis perverted and forever altered this once positive symbol.

The sudden adoption of the swastika by the Nazis in 1920 seems bizarre, considering the symbol’s original meaning and its association with peoples who the Nazis would have viewed as lower races. So how and why did the Nazis come to use this ancient, venerated symbol?

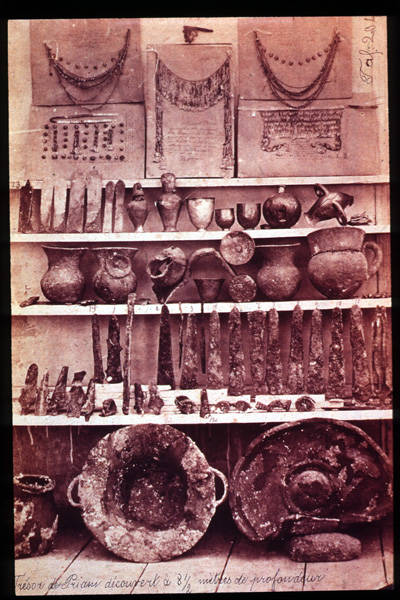

Wikimedia CommonsArtifacts unearthed by Heinrich Schliemann’s team at the Troy excavation site.

Credit for the Nazis’ misappropriation of the swastika goes back to the ancient city of Troy. Not to the time when the Trojans still lived in their great city, but to 1871 when it was discovered by a German businessman-turned-archaeologist named Heinrich Schliemann.

Schliemann was obviously no Nazi (the Nazis would not even exist until decades later). Instead, Schliemann became obsessed with finding Homer’s Troy. He did not view the ancient Greek poet’s epic Illiad as a legend but rather as a map, a text that offered clues that could lead him directly to the fabled city.

And Schliemann, following up on prior work done by English archaeologist Frank Calvert, did actually find the site generally believed to be Troy on the Aegean coast of Turkey. There he used blunt methods of excavation to dig as deep and as far and as quickly as possible. Seven layers of other civilizations were stacked on top of each other with Troy at the bottom.

And throughout these various layers, Heinrich Schliemann found scores of potsherds and artifacts adorned with swastikas. At least 1,800 variations of the symbol were found.

After excavating at Troy, Schliemann then went on to find swastikas everywhere from Greece to Tibet to Babylonia to Asia Minor. Funny enough, he drew a connection between the swastika and the Hebrew letter tau, the sign of life, which believers drew on their foreheads (this was apparently serial killer Charles Manson’s reasoning for later carving a swastika into his forehead).

Wikimedia CommonsNon-Nazi swastikas around the world, clockwise from top left: a Byzantine church in present-day Israel, an ancient Roman mosaic in Spain, a Hindu temple in Indonesia, and a Native American basketball team in the U.S.

However, scholars like The Swastika author Malcolm Quinn claim that Heinrich Schliemann didn’t actually know what these symbols were and instead relied on other supposed authorities to interpret their meanings for him.

One of those supposed authorities was Emile Burnouf of the French School at Athens, an archaeological institute. Burnouf, both an avowed anti-Semite and a scholar of ancient Indian literature, worked for Schliemann as a cartographer, but he was more teacher than assistant.

Because the swastika was known to be common in Indian religion and culture, Burnouf turned to the sacred, ancient Hindu epic known as the Rigveda to interpret — or reinvent — the meaning of the swastika.

And in addition to referencing the swastika, this text and others like it also make reference to “Aryans,” a term used by some ancient peoples in modern-day India starting in the sixth century B.C. to mark themselves as a circumscribed linguistic, cultural, and religious group amongst the other such groups in the area at the time.

It’s true that the term “Aryan” in this sense encompassed certain connotations of this group’s self-proclaimed superiority over other groups in the area at the time. Some theories hold that these Aryans invaded present-day India from the north thousands of years ago and displaced the region’s darker-skinned inhabitants.

Nevertheless, Burnouf misinterpreted (both foolishly and willfully) the racial superiority implications in these texts and ran with them. Burnouf and other writers and thinkers across Europe in the late 1800s used the presence of the swastika in both these ancient Indian texts and at the Troy excavation site to conclude that the Aryans were once the inhabitants of Troy, which Heinrich Schliemann had fortuitously found.

And because Heinrich Schliemann had found the swastika at dig sites elsewhere across Europe and Asia, theorists like Burnouf were able to concoct a master race theory claiming that Aryans, with the swastika as their symbol, had gone from Troy through Asia Minor and down to the Indian subcontinent, conquering and proving their superiority wherever they went.

Wikimedia CommonsRight-wing German revolutionaries participate in the Kapp Putsch of 1920, an attempted coup designed to overthrow the Weimar Republic after that government ordered the disbandment of the Freikorps. Note the swastika on the front of their vehicle.

Then, after various linguists made connections between the ancient Aryan language and modern-day German, many Germans caught up in the rising tide of nationalism both before and after World War I began claiming this Aryan “master race” identity as their own.

German nationalist groups such as the anti-Semitic Reichshammerbund and the Bavarian Freikorps, a paramilitary group that wanted to overthrow the Weimar Republic, then built upon this perceived German-Aryan connection and picked up the swastika as a symbol of German nationalism (before the Nazis did).

When the swastika was adopted as the symbol of the Nazi party in 1920, it was because it was already being used by other nationalist and anti-Semitic groups in Germany. After the Nazis came into power in the early 1930s, the swastika became ubiquitous at party rallies, athletic events, on buildings, uniforms, even Christmas decorations and was thus programmed into the mass consciousness and given a meaning very different than the one it’d had for thousands of years elsewhere around the world.

PixabayNazi swastikas adorn government buildings in Berlin. 1937.

And while scores of bigoted and misguided scholars and politicians helped change the meaning of the swastika over the course of several decades, none of it likely would have happened at all if not for the discoveries of Heinrich Schliemann.

After this look at Heinrich Schliemann, read up on the Nazi Lebensborn program designed to create a master race. Then, view some of the most powerful photos taken during the Holocaust.