Once the highest-paid screenwriter in Hollywood, Herman Mankiewicz co-wrote "Citizen Kane" with Orson Welles before succumbing to alcoholism in 1953.

Herman J. Mankiewicz saw Hollywood as a gold mine. Moving to the West to take a screenwriting job in 1926, he invited more East Coast writers to share in the film industry’s easy money. “Millions are to be grabbed out here and your only competition is idiots,” Mankiewicz telegrammed to a friend. “Don’t let this get around.”

However, Hollywood success came at a cost. A notorious gambler and alcoholic with an acerbic wit, Herman “Mank” Mankiewicz wrote nearly 60 film scripts — with mostly no credit. But then, a writing credit on the 1941 film Citizen Kane made him a sensation almost overnight. From production to promotion, Mankiewicz’s work on the movie courted quite a bit of controversy.

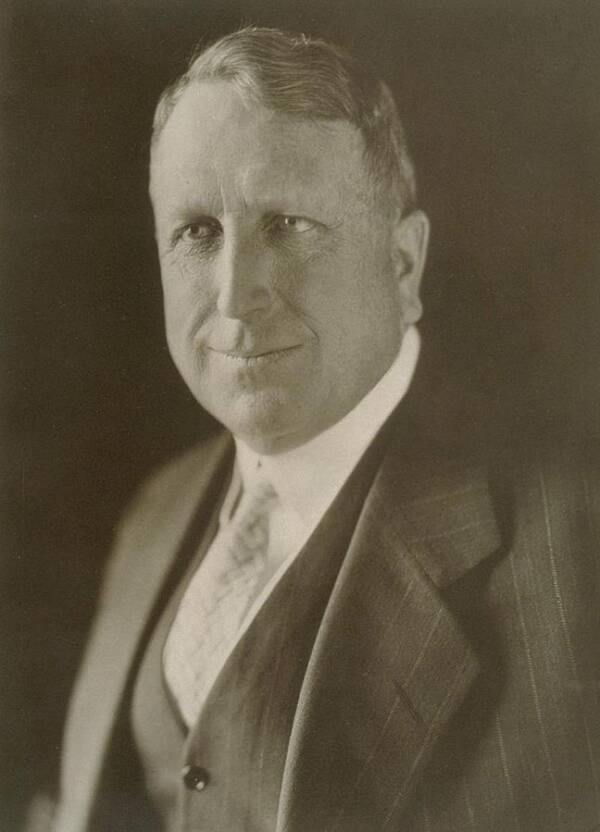

John Springer Collection/CORBIS/Corbis/Getty ImagesHeadshot of Herman Mankiewicz, the co-screenwriter of Citizen Kane. Circa 1940s.

Mankiewicz angered media mogul William Randolph Hearst by allegedly using details of his private life for the film’s plot. He also fought with director Orson Welles over credit as the film’s screenwriter. The debate over who really wrote the film would follow both men to their graves.

But in the end, Herman Mankiewicz got the last laugh, the credit, and the Oscar he deserved.

The Early Life Of Herman J. Mankiewicz

Born on November 7, 1897, in New York City, Herman Jacob Mankiewicz grew up in Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania. Under pressure from his father to excel at an early age, he became a whiz kid and graduated from Columbia University before his 19th birthday.

“A father like that could make you either very ambitious or very despairing,” Mankiewicz once shared. He famously chose despair — but he also developed a sharp tongue.

While working as a press agent and drama critic in New York, Mankiewicz joined the legendary Algonquin Round Table social circle. According to the Table’s writers and critics, which included Dorothy Parker and George S. Kaufman, Mankiewicz’s alcohol-laced wit was supreme.

Indeed, Algonquin member Alexander Woollcott once called Herman Mankiewicz the “funniest man in New York.” After his comedy caught the attention of producer Walter Wanger, Mankiewicz was invited to Hollywood for a gig as a screenwriter. And his life changed forever.

How Herman J. Mankiewicz Became Hollywood’s Script Doctor

Wikimedia CommonsScreenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz worked on more than 60 films, including Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, starring Marilyn Monroe.

Film work at Paramount came easy to Herman J. Mankiewicz. First, he started with silent films and then transitioned to “talkies.” As head of the studio’s scenario department, he was one of the highest-paid writers in Hollywood.

At any chance he got, Mankiewicz let the studio execs know he was the brains of it all. As a result, his wisecracking, fast-talking style marked the movies of the time.

In all, Herman Mankiewicz worked on nearly 60 film scripts, many of which were among the best-known Hollywood films of the era, including Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Dinner At Eight, and Wizard of Oz. Although most of his films were witty and wry, he also kept up with current events.

In 1933, Mankiewicz took a break from the studio to write The Mad Dog of Europe. The screenplay was a thinly-veiled swipe at Adolf Hilter’s rise to power in Germany.

The topic hit close to home. Mankiewicz’s parents were German-Jewish immigrants, and most of the studio heads were Jewish as well. However, the film was dead in the water. With a clear anti-Hitler message, many feared the screenplay would make the Nazis furious. And they were right.

Joseph Goebbels, who was Hitler’s minister of education and propaganda, even told MGM that none of Mankiewicz’s films could be shown in Germany unless his name was removed.

Meanwhile, the studios refused to make the movie, with one producer saying, “We have interests in Germany; I represent the picture industry here in Hollywood; we have exchanges there; we have terrific income in Germany and, as far as I am concerned, this picture will never be made.”

Of course, this would not be the last controversy associated with Mankiewicz’s name in Hollywood.

The Citizen Kane Writing Scandal

Library of CongressOrson Welles, the director and star of Citizen Kane. March 1, 1937.

Working on films with no credit was common under Hollywood’s studio system at the time. As directors craved more control, studio contracts laid out who would get credit for what and how much credit they would get. So when RKO studios decided Herman J. Mankiewcz would get no credit for writing Citizen Kane, he didn’t mind at first.

RKO studios wanted its “Boy Wonder” Orson Welles to write, direct, and star in the film. They paid Welles $100,000 (around $1.75 million today) for the job. Meanwhile, Mankiewicz made $1,000 a week and a $5,000 completion bonus to take no credit.

Since Welles knew Mankiewicz’s work from the CBS radio series, The Campbell Playhouse, he asked him to help write the script. But Mankiewicz’s drinking and gambling had already made him a notorious figure in Hollywood by that point. So, Welles reportedly asked John Houseman, his partner in the Mercury Theater, to help keep Mankiewicz on track.

Wikimedia CommonsHerman J. Mankiewicz co-wrote Citizen Kane with Orson Welles, pictured here as Charles Foster Kane in the film.

The studio agreed to the team, but things were rocky from the start. A total of seven drafts were written — and the final script ended up being 156 pages. In the end, Mankiewicz felt that the script was a team effort and wanted credit for the final film.

Per his contract, Welles initially refused. However, as the buzz around Citizen Kane grew, Herman Mankiewicz continued to fight for his recognition. He knew the film would be a big success, and it ultimately was.

After Mankiewicz threatened Welles with legal action, the studio finally settled the fight with joint credit on the film. But even after Citizen Kane was released, the credit feud between Herman J. Mankiewicz and Orson Welles was still the talk of the town. And that wasn’t the movie’s only controversy.

How William Randolph Hearst Allegedly Inspired Citizen Kane

Wikimedia CommonsWilliam Randolph Hearst, photographed here in 1910, reportedly inspired the Charles Foster Kane character in Citizen Kane.

When Citizen Kane won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay, both Herman Mankiewicz and Orson Welles received credit but neither man showed up for the award. The feud would ultimately follow both men beyond their graves.

In a 1971 essay for The New Yorker titled “Raising Kane,” film critic Pauline Kael called Mankiewicz the true “loser-genius” of the film. On the other hand, critic Peter Bogdanovich countered with “The Kane Mutiny” in Esquire, citing Welles as an equal co-author of the script.

Decades later, Mankiewicz’s son Frank wrote in a memoir that his father agreed to share credit with Welles as a favor. However, Welles allegedly wrote “not one word” of the movie.

On the other hand, there were others who maintained that the film was mostly Welles’ masterpiece — and that he was the true “Boy Wonder” behind not only the character but the story as well.

In 2016, The Smithsonian reported:

“Analyzing two overlooked copies of a Kane ‘corrections script’ unearthed in the archives at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and the University of Michigan, the journalist-turned-historian Harlan Lebo found that Welles revised the script extensively, even crafting pivotal scenes from scratch — such as when the aging Kane muses, ‘If I hadn’t been very rich, I might have been a really great man.'”

Although there are many hot takes on who wrote what, it cannot be denied that Mankiewicz played an important role. The film’s character Charles Foster Kane was widely considered a carbon copy of media tycoon William Randolph Hearst. And this was largely thanks to Mankiewicz.

When Herman Mankiewicz had first arrived in Hollywood, he had made friends with director Charles Lederer. He was a nephew to Hearst’s mistress, actress Marion Davies. As a result, Mankiewicz entered Hearst’s social circle.

At parties and other high society socials, Mankiewicz made the guest list. However, his drinking got the best of him, and Hearst quickly shut him out. Bitter and full of despair, Mankiewicz allegedly turned his wit on Hearst.

Using what he knew from his unique access to Hearst’s inner circle, Mankiewicz helped create the script for Citizen Kane.

Blackmail, Bullying, And Other Scandals Behind Citizen Kane

Wikimedia CommonsActress Marion Davies may have inspired the “Rosebud” reference in the film Citizen Kane.

Scandals rocked Citizen Kane from start to finish and Hearst wanted the film shut down over its alleged portrayal of his mistress Marion Davies.

Reportedly, Hearst was especially furious over the film’s “Rosebud” reference, which may or may not have been his pet name for Davies’ “womanly divide.” However, others insist he was simply upset that people took the film to be an exposé of his life.

As a result, Hearst tried to have Welles branded as a communist. Meanwhile, Herman J. Mankiewicz called the American Civil Liberties Union to stop Hearst’s newspapers from the constant attacks in the press.

“This is not a tempest in a teapot, it will not calm down, and the forces opposed to us are constantly at work,” Welles’ lawyer and manager Arnold Weissberger said in a 1941 memo. Researcher Harlan Lebo later published this warning in his book, Citizen Kane: A Filmmaker’s Journey.

But despite all the scandals surrounding its release, Citizen Kane would go on to become the greatest film of all time, at least according to many critics. However, Herman Mankiewicz’s story did not have a Hollywood ending.

Herman J. Mankiewicz: Triumph And Tragedy In Hollywood

After a decade in the film industry, Herman J. Mankiewicz felt like he never really left his mark on Hollywood. After early successes, his work was drying up. He was 44 when he started working on Citizen Kane. In contrast, Orson Welles was 25 with much more of a career ahead of him.

The film they created together was their finest work, and Mankiewicz wanted to hang on to that.

For this reason, the idea of Welles taking sole writing credit angered him. “I’m particularly furious at the incredibly insolent description of how Orson wrote his masterpiece,” Mankiewicz said in a letter to his father. “The fact is that there isn’t one single line in the picture that wasn’t in writing – writing from and by me – before ever a camera turned.”

More often than not, Mankiewicz was the smartest person in the room. But his drinking problem ultimately got in the way of a true triumph. He died from bad kidneys in 1953 at age 55.

On his destructive behavior, Mankiewicz once wrote: “I seem to become more and more of a rat in a trap of my own construction, a trap that I regularly repair whenever there seems to be danger of some opening that will enable me to escape. I haven’t decided yet about making it bomb proof. It would seem to involve a lot of unnecessary labor and expense.”

Ultimately, Welles saw the loser and genius in Herman Mankiewicz — even after he died. Despite their intense feud, Welles was quoted as saying, “He saw everything with clarity. No matter how odd or how right or how marvelous his point of view was, it was always diamond white. Nothing muzzy.”

Now that you’ve read about Herman J. Mankiewicz and the true story behind “Mank,” check out these photos of vintage Hollywood and see these famous Hollywood couples that time almost forgot.