For 30 years, the U.S. government deliberately exposed thousands of its people to life-threatening radiation. Modern scholarship reveals how far the project went.

Engineers drilling and weighing a plutonium casting in one of the glove boxes at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment. Photo: Reg Birkett/Keystone/Getty Images

A poorly attended ceremony took place at the White House on October 3, 1995. Hosted by President Bill Clinton, the event marked the official receipt of the final report from a presidential advisory committee he had ordered into existence the year before.

The committee was to investigate the U.S. government’s secret program to expose human test subjects to radiation without their knowledge or informed consent.

The findings were chilling. At least 30 programs, beginning in 1945, saw government scientists knowingly exposing American citizens to life-altering levels of radiation, sometimes by directly injecting plutonium into their bloodstreams, in order to develop exposure data and plan for the effects of a nuclear war.

Children and pregnant mothers had been given radioactive food and drink, and soldiers had been marched over radioactive dirt at active test sites. In some cases, graves of the dead were robbed to secretly examine the remains of those killed by the studies. Virtually none of these actions were done with consent from the people involved.

Trillions Of Bullets Every Second

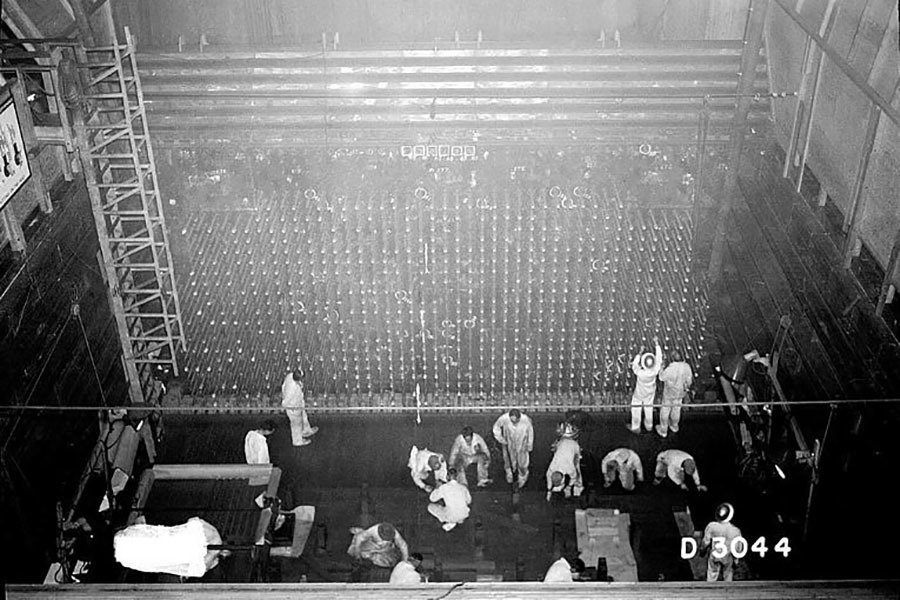

The Hanford B Reactor, the first plutonium producer, under construction. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Plutonium was first isolated in the early 1940s, during the research that eventually grew into the Manhattan Project, which produced the world’s first atomic bombs. The metal, a byproduct of uranium fission, is basically harmless outside the body; its alpha particles travel only a short distance through the air and are easily stopped by human skin and clothes.

Inside the body, it’s a different story. If plutonium enters the body as a dissolved solution or airborne dust, the constant barrage of radiation breaks down DNA and damages the body’s cells, as if the contaminated person was being shot with trillions of tiny bullets every second from the inside.

Any exposure to plutonium raises your risk of cancer over a lifetime, and high doses cause enough damage to kill over a range of seconds to months, depending on the dose received.

On top of the radiation threat, plutonium is also a heavy metal, like lead or mercury, and is about as toxic as both. A 150-pound adult who consumes 22 mg of plutonium, or about 1/128 of a teaspoon, has a 50 percent chance of dying just from the poisoning before the radiation effects even come into play.

Manhattan Project workers, ignorant of the risks, routinely handled plutonium with their bare hands and breathed in the dust inside their closed, poorly ventilated laboratories. As Eileen Welsome, the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of The Plutonium Files told ATI:

In 1944, all the plutonium in the world could be fit on the head of a pin. But as more and more plutonium was produced, it began to get tracked about the laboratories like flour.

Nasal swabs kept coming back positive for plutonium dust, and workers’ urine and feces emitted detectable amounts of alpha radiation. Nobody in charge of the project knew how serious this problem was, and animal tests didn’t give very clear answers to how much plutonium was absorbed by the body or how quickly it could be excreted.

Human test subjects were needed, and by the spring of 1945, they were available.

21 Years Of Torture

A man handles plutonium. Photo: YouTube

The first round of tests involved 18 patients who had been diagnosed with terminal illnesses. The idea was to secretly inject them with plutonium and track its absorption and record the health effects before the subjects died of their preexisting illnesses.

Plutonium, known as “49” or “product,” was transported from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory to the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center (UCSFMC) in solution to be administered via IV drip. Urine and stool samples would then be collected from the dying patients and analyzed for signs of radioactivity.

This didn’t always go according to plan, as in the case of 58-year-old house painter Albert Stevens. Stevens was admitted to UCSFMC in 1945 with a severe gastric ulcer that was misdiagnosed as terminal cancer. Given just a few months to live, on May 10, 1945, Stevens was administered the largest dose of plutonium any human has ever received; just under one microgram.

The sample consisted of two isotopes of plutonium, one weakly radioactive with a 24,100-year half-life, the other highly radioactive with an 87.7-year half-life. For the rest of his life, Stevens was given free medical care (and more secret testing) at UCSFMC as his health deteriorated. As the plutonium in his bones weakened his spinal column, and as his eyes fogged up with cataracts, the doctors periodically operated on Stevens to remove parts of his liver, spleen, pancreas, and lymph nodes.

Nobody ever told him or his family that the cancer diagnosis had been erroneous. They simply assumed he had been given experimental cancer therapy, and that it had worked.

Stevens died on January 9, 1966, of a heart attack that doesn’t seem to have been related to the plutonium. Over the 21 years that passed from his dosing to his death, Stevens absorbed more radiation than any other human being; 6,400 rem, or 60 times the government’s maximum safe lifetime exposure.

Until the files were declassified, Stevens was known only as CAL-1. Another patient in this first test series, known as CAL-2, was a four-year-old boy named Simeon Shaw. Another test subject was a baby.

“A Touch of Buchenwald”

Photo: Twitter

The early experiments in unwitting human radiation exposure were carried out under the umbrella of the Manhattan Project and overseen by a medical researcher named Joseph Hamilton. Hamilton had been the man who withdrew the plutonium from the lab and transported it to the hospital for injection.

Between 1945 and 1947, Hamilton was more involved in government radiation studies than perhaps any other researcher. A world-class expert on radiation’s effects on living tissue, Hamilton even experimented on himself, repeatedly drinking or rubbing his skin with radioactive samples to develop data.

After 1947, as the Manhattan Project gave way to the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), Hamilton returned to his Berkeley lab and took on more of a consultant role for the human trials. In 1950, he wrote what has since become known as the “Buchenwald Memo.”

In this letter, addressed to the AEC chairman in response to a planned second round of experiments, Hamilton urged the end of human testing because it could damage the commission’s reputation and it had, as he put it, “a little of the Buchenwald touch,” in reference to the notorious Nazi concentration camp where hundreds of horrendous medical experiments were carried out on prisoners.

Hamilton’s advice was ignored. The commission was flush with grant money, so researchers affiliated with the research arm selected another 88 test subjects at the University of Cincinnati and exposed them without consent to hefty doses of radiation under the direction of Dr. Eugene Saenger between 1960 and 1971.

Joseph Hamilton didn’t live to see the results. He died of radiation-related leukemia in 1957, at age 49.

Joseph Hamilton downs a radioactive solution of water and sodium.

The Cincinnati trials were horrific. Saenger picked test subjects from poor, mostly non-white groups of cancer patients and exposed them – again, without a hint of informed consent – to extreme doses of whole-body radiation.

Some patients were left on the table and dosed with radiation for a solid hour, during which time they were exposed to the equivalent of 20,000 chest X-rays. Roughly one in four patients died as a direct result of the tests, and the rest suffered through the whole appalling rainbow of symptoms of radiation sickness: nausea, uncontrollable vomiting, severe mental confusion and other neurological effects, loss of hair, loss of appetite, loosened teeth, mouth ulcers, and a dramatically elevated lifetime risk of cancer.

Nobody really knows what Saenger was trying to prove in these treatments, since the type of cancer his victims had was already known not to respond to whole-body irradiation, especially not to lethal doses of it rammed home in marathon sessions.

Justice never caught up with Saenger. A graduate of Harvard Medical School, his 30-year teaching career was unblemished by any hint of scandal. He won plenty of awards for his pioneering research, lived as a pillar of his community, and died in 2007, at age 90.

His obituaries in the Los Angeles Times and Cincinnati Enquirer were fawning tributes to his contributions to science. This despite the fact that his actions became public in 1999, when the (very few) survivors of his trials managed to wring a $3.6 million settlement out of him, which works out to just under $41,000 per person who got a life-shattering dose of radiation, not counting legal fees.

Oatmeal Is Good For Kids

A replica of an early general store depicting two seniors looking at an old-fashioned box of Quaker Oats during the Senior Citizens Night at the Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago, Illinois, 1975. Photo: Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago/Getty Images

Eugene Saenger’s work stands out for its appalling cruelty, but he was hardly acting alone. Dozens more tests were conducted between 1945 and 1975, always in the deepest secrecy and with endless misdirection and lies to cover them up.

Between 1946 and 1953, for example, the Quaker Oats company contracted with the Department of Energy to test some of the claims its advertising department was making about their oatmeal’s nutritional value.

For the test, Harvard and MIT scientists recruited 57 mentally challenged and institutionalized boys into a “science club” that hosted fun activities and trips to see the Red Sox play at Fenway Park. When the kids got hungry for lunch, they were fed oatmeal and milk that had been laced with radioactive isotopes of calcium and iron.

Their stool was then checked for radioisotopes to work out how much iron and calcium the children were getting from their food. This information was then forwarded to Quaker Oats to help them craft ad campaigns that touted the health benefits of oatmeal.

In another series of tests, running from 1946 to 1949 and intended to study maternal iron absorption, over 800 poor women living in and around Nashville were deceived into taking part in a nutritional study funded by Vanderbilt University. The Vanderbilt experiment, as it came to be known, saw pregnant women given pills with radioactive iron-59 and tested for iron levels on subsequent visits.

When the babies were born, they too were tested to see how much iron had passed through the placenta (between two and three percent). The babies were also dosed with between five and 15 rads in the womb.

While it’s true that this small amount of radiation exposure is roughly the sameas what you’d get in one year spent living at a high altitude — such as in Denver — remember that nobody at the time knew how much radiation would be delivered to the developing fetuses or what the effects would be. It could have been much, much worse, and they were willing to make that gamble.

It is also worth noting that the mothers were not made aware of the potential harm, nor were they recruited from Nashville’s middle or upper classes — the groups more likely to have lawyers.

An Ill Wind Blows Nobody Good

A nuclear weapons test. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

While testing had already been done on pregnant women, mentally handicapped children, and cancer patients, the Pentagon apparently felt it needed actual exposure data from healthy young test subjects to really get a picture of what would happen when Soviet communists finally dropped the bomb on America.

To get that data, the military knowingly exposed soldiers and civilians living near nuclear test sites to radioactive fallout.

During the summer of 1957, the United States carried out 29 nuclear tests in Nevada as part of Operation Plumbbob. These tests threw a lot of radioactive debris into the air, which then traveled downrange into communities that are now known as “Downwinders.”

Radioactive fallout dispersed on the wind, and the heavier bits settled out and entered the groundwater. Downwinder communities show a marked increase in thyroid cancers and leukemia, which may have killed between 1,000 and 20,000 people who would not otherwise have developed cancer.

Photo: YouTube

In order to test troops’ ability to operate in a tactical nuclear environment, infantry soldiers were sometimes exposed to fallout by marching them through the test sites before the primary radiation had a chance to die down. During the Desert Rock VII and VIII maneuvers alone, about 18,000 soldiers were deployed into the hot zone immediately after the test shots.

A 1980 survey found that the exposed personnel had developed double the lifetime risk of leukemia and other cancers.

Experiments of Opportunity and Mental Gymnastics

A Hiroshima victim is examined for radiation exposure.

The men who carried out this research were awfully cavalier about exposing people to radioactive substances, and they were even more relaxed about getting consent, but they weren’t monsters. About the researchers’ mindsets, Eileen Welsome says:

“I think scientists who did these kinds of experiments were great at rationalization. They thought the studies were for a greater good. Whenever there was a nuclear accident, the scientists and doctors swooped in to study the effects. They studied the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the soldiers at the Nevada Test Site, and employees injured in criticality incidents. These studies were called “experiments of opportunity.” A Los Alamos employee named Cecil Kelly was fatally injured in a criticality incident in the 1950s and the doctor/scientists rushed to the hospital to get samples of his blood, vomit, [and] bone marrow. They even saved his brain and sent it to a military institute.”

Convinced that most of what they were doing was either harmless or for the greater good, few of the researchers involved with the tests ever raised an alarm or complained in public about the secret projects.

Everybody had a career to look out for, after all, and nobody wanted to get in trouble. Besides, most of the test subjects were unaware of what had happened to them, and the majority were poor, black, or under military discipline and unlikely to complain about health problems that in any event mostly likely wouldn’t surface until decades later.

Peeling Back The Veil, One Inch At A Time

Al Gore’s investigation into U.S. radiation experiments failed to turn up much.

Exposing the truth about decades of government radiation experiments wasn’t easy.

Starting in the 1970s, journalist Howard Rosenburg published a series of articles built on his Freedom of Information Act filings. The articles, particularly one in a 1981 issue of Mother Jones, finally got some attention.

The House Science and Technology Committee investigated the matter under the leadership of Tennessee Representative Al Gore. Hearings were held in secret, and the names of participants were not disclosed. The committee’s final ruling was that the experiments were, in the words of the report: “satisfactory, but not perfect.”

Sensing that the Gore committee might have been a whitewash, Representative Ed Markey held hearings of his own and demanded that the nearly 700 victims be located, named, and compensated for the crimes committed against them.

Nothing of the sort happened. The Markey report got little news coverage, the Reagan Administration successfully fought declassification, and the story quietly went away.

Representative Ed Markey.

While looking into an unrelated matter, Eileen Welsome stumbled across some odd paperwork on an Air Force base in 1987 that referred to irradiated animal carcasses and hinted at data from a few human subjects who were identified only by code names.

Over the next six years, Welsome successfully dug out the names of the 18 Manhattan Project patients and tracked them down for her articles exposing the program for the Albuquerque Tribune. It was this series of high-profile exposures — especially the living, breathing victims who had at last been named through Eileen’s research — that motivated the 1995 presidential committee’s report.

After sifting through over 840,000 pages of material, and ordering the declassification of thousands of documents, the committee finally delivered its findings.

The report acknowledged that “wrongs were committed,” but declined to list any indictable offenses that could be pinned on any living individuals. The experiments involving pregnant women and disabled boys were dismissed as “not harmful” and ignored thereafter. Worse, no structural reforms were suggested to make sure things like this would never happen again in America.

President Clinton expressed his personal sorrow at the misfortune of the victims, but stopped short of offering real relief.

The October 3, 1995 ceremony got little attention. It was scheduled for the day a Los Angeles jury acquitted O.J. Simpson of murder. By the time everybody was done talking about that, news of the committee’s report had quietly died. The issue has not been revisited since.

Next, read about the shocking conspiracies about the US government that are actually true. Then, read up on the horrific experiments of Nazi doctor Josef Mengele.