IBM and the Holocaust

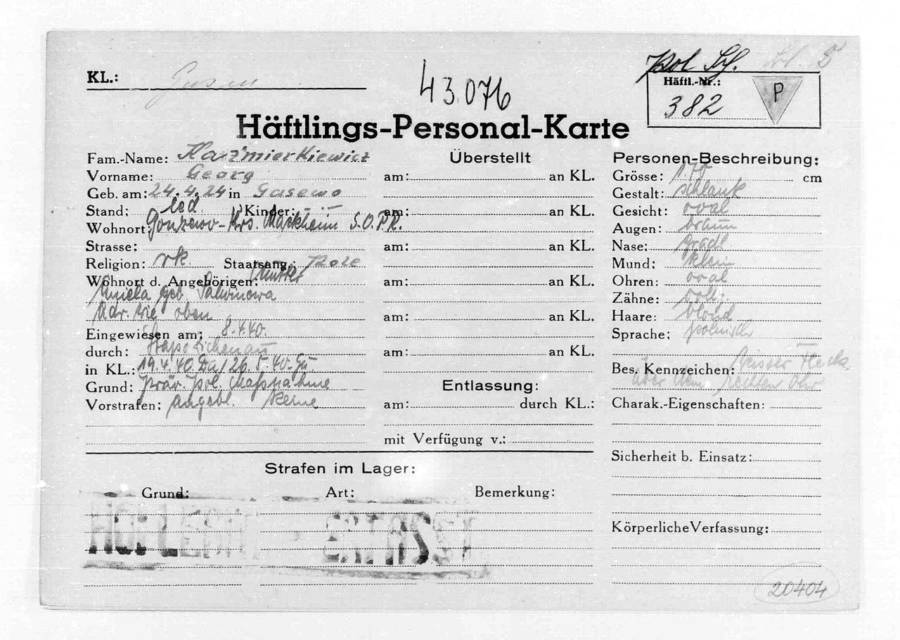

Wikimedia CommonsA Hollerith punch card used for a prisoner at Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp.

In contrast to IBM’s narrative, Edwin Black’s book casts a more critical eye toward Watson’s actions in the years leading up to World War II.

That story begins two months after Hitler became Germany’s chancellor in January 1933, at which point he established the first concentration camp for political prisoners. By the next month, 60,000 were imprisoned.

This is when the German government revealed its plan to hold a long-delayed national census. This type of business was IBM’s bread and butter and Dehomag, the German subsidiary, was first in line for the job. IBM thus boosted its investment in Dehomag almost 20-fold, with that money largely going toward building IBM’s first factory in Germany.

According to Black, the Nazi government then used the equipment and training IBM had invested in the German market to identify so-called undesirables. After the Nazis completed the census, they discovered that two million people of Jewish descent lived in Germany — not half a million, as they’d previously thought.

As the Nazis began taking action against them, public calls for the U.S.’ economic boycott of Germany commenced. However, according to Black at least, IBM ignored the outcry. In fact, the person in charge of Dehomag — Willy Heidinger — was an outright Nazi supporter, thus making Dehomag friendly to the regime. Black contends that as it became increasingly difficult to conduct business in Nazi Germany, Watson and Heidinger made a secret deal to use Heidinger and Dehomag’s clout with the Nazis to supply punched-card technology to IBM customers in territories that had recently come under Nazi control.

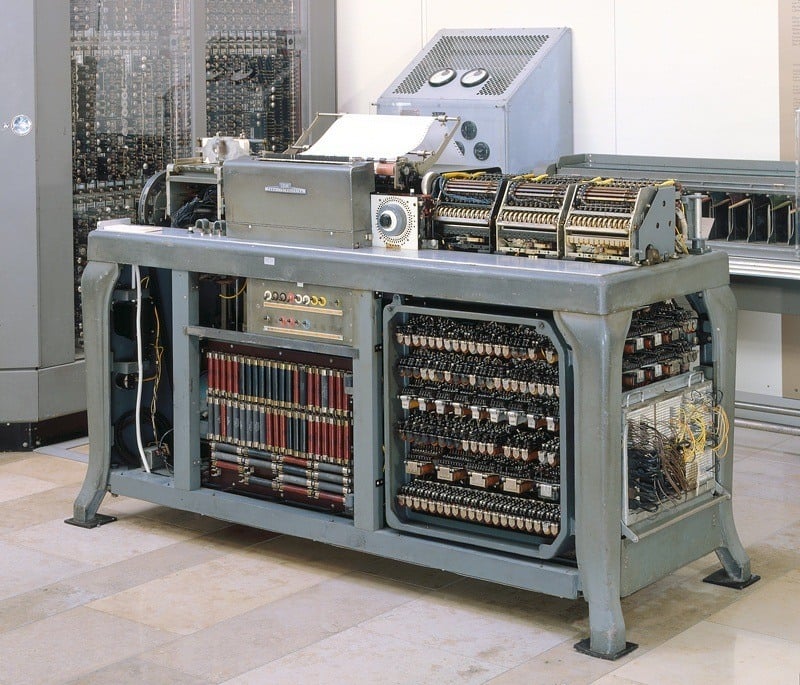

Deutsches MuseumMachines like this — the Dehomag Tabulator D11, made by an IBM subsidiary — were used to carry out the Holocaust.

Bolstering this theory, in the 2012 reissue Black presents a letter dated 1941 from IBM that directed a Dutch subsidiary to work with Dehomag — years after business with Germany was supposed to have ceased. Furthermore, according to Black’s 2012 evidence, Watson took a one percent commission on all profits made in business with the Nazis, and had to personally approve all expenditures on said business, such as bomb-fortifying Dehomag installations.

The most damning of Black’s new evidence, however, is likely two U.S. government memos. The first is a Justice Department memo written during a federal investigation into IBM’s collaboration with the Nazis. In that memo, Economic Warfare Section Chief Investigator Howard J. Carter wrote, “What Hitler has done to us through his economic warfare, one of our own American corporations has also done . . . Hence IBM is in a class with the Nazis . . . The entire world citizenry is hampered by an international monster.”

The second memo, dated four days before Pearl Harbor, comes from the State Department. IBM’s top attorney, Harrison Chauncey, had visited the State Department to discuss IBM’s involvement with the Nazis. The memo read that Chauncey expressed anxiety “that his company may some day be blamed for cooperating with the Germans.”

Given the case Black makes against IBM, his book has faced rather critical reception. When it first came out, for example, Bloomberg Businessweek and The New York Times skewered it, citing faulty research methodology and bombastic hyperbole.

In response, Black simply directed ATI to a page on his website that lists the various media outlets that have criticized his book but later published retractions. Elsewhere Black has publicly stated that criticism comes from dislike of his person, not what appears in his work.

Indeed, as Mic puts it:

“Despite Black’s firebrand ethos, his meticulous research has uncovered tens of thousands of documents, culled together from across Europe, that carefully show how IBM didn’t just provide technology to Hitler’s Germany — it helped implement and maintain it for whatever purposes the Nazis required.”

In fact, Newsweek, The Sunday Times, and The Washington Post all gave Black’s book positive reviews.

Whatever your take on the book, it’s clear that Black indeed conducted copious research through scores of documents that the rest of the world has simply ignored. Even New York University and the University of Stuttgart, the two institutions to which IBM sent their World War II-era documents, haven’t given that evidence a close look.

When ATI reached out to both institutions and asked to be put in touch with an expert who had studied the files, Stuggart responded by saying that the files likely didn’t exist in their archives, while NYU said that they’ve acted only as a repository for the documents — and that much of the collection relates to IBM’s subsequent efforts to regain shareholder control of its German subsidiaries and machines after Allied victory.

As NYU states, we shouldn’t forget that even after the Holocaust shocked the world, IBM sought to regain control of its interests in Germany. Clearly, no matter what the circumstances, this company always had its eye on the prize, and knew precisely what it was doing. That’s why it’s hard to believe that, when it comes to doing business with the Nazis, IBM wasn’t aware of what it was doing in every sense.

And in the early 2000s, some people wanted to call IBM on it. In 2001 and 2004, victims of Nazi persecution filed two class-action lawsuits against IBM. In 2006, a Swiss court deemed the statute of limitations to have expired and dismissed the 2004 case, while the 2001 case disappeared when the plaintiffs’ lawyers withdrew it the same year. In that case, the decision to withdraw came after several German companies that had contributed to a Holocaust victims reparations fund threatened to stop donating unless any and all legal action was off the table. Not wanting to shortchange that fund, the lawyers withdrew the case.

Ultimately, IBM Germany did agree to donate $3 million to that Holocaust fund — with the clear stipulation that the contribution was not an admission of liability.

Next, learn about Coca-Cola’s jaw-dropping history with the Nazis, before checking out the secret Nazi base in the Arctic.