Though ibogaine has helped some people who are addicted to opioids, the drug remains controversial — and illegal in the United States.

Anyone who struggles with opioid addiction knows how difficult it is to quit. That’s why some activists are frustrated that so few people have heard of ibogaine — a naturally occurring psychoactive substance that some say can help reduce opioid withdrawal symptoms.

An herbal psychedelic with a rich history, ibogaine was first used by the Pygmy tribes of Central Africa for spiritual rituals. Then, French explorers brought it back home, introducing ibogaine to the rest of the world.

Wikimedia CommonsThe powdered root of the iboga tree, which is where ibogaine comes from.

Since its discovery, ibogaine has been used for a variety of purposes. Some have used it recreationally. Others — like the CIA — are rumored to have investigated it as a potential tool of warfare.

But ibogaine’s most compelling use may be that it can help addicts quit using opioids. So, why haven’t we heard more about it?

The Afro-French Origins Of Ibogaine

Ibogaine is a compound found in the roots of iboga and other plants of the Apocynaceae family, which grows in West Africa and Central Africa.

Pygmy tribes in Central Africa were the first to discover these plants. It’s unknown exactly when they started using them for rituals, but the practice is said to date back centuries or even millennia. Pulling roots and bark from the iboga plant, they chewed on these pieces to induce a psychedelic state that was ideal for spiritual ceremonies.

This practice eventually spread from the Pygmies to the Bwiti people of Gabon, a country on the western coast of Africa. And when the French began exploring Gabon in the late 19th century, they found out about the plant — and its powerful psychedelic side effects.

Intrigued, the explorers brought the iboga plant back to France for study.

Wikimedia CommonsFrench explorers first learned about the iboga tree in the late 19th century.

In 1901, French scientists isolated ibogaine from the iboga plant. And they soon discovered that when used in low doses, the psychedelic was able to reduce fatigue without producing significant hallucinogenic effects.

As a result, the French began to market ibogaine as a stimulant under the name Lambarène in the 1930s. It was meant to help people suffering from depression, low energy, and infectious diseases. It also became popular among athletes who were looking for an energy boost.

However, Lambarène was pulled from the shelves in the 1960s because doctors realized that long-term use could potentially lead to cardiac arrest. Around the same time, other countries had begun to criminalize ibogaine because of its hallucinogenic and heart-related side effects.

But some organizations saw more potential for ibogaine — beyond just getting high or treating medical conditions.

MKUltra: The CIA’s ‘Mind Control’ Experiments

Getty Images

Dr. Harry L. Williams squirts LSD from a syringe into the mouth of Dr. Carl Pfeiffer, a CIA MKUltra consultant, at Emory University in Georgia. 1950.

One of the most fascinating rumors surrounding ibogaine is that the CIA may have attempted to harness its powers as a tool of warfare.

During the CIA’s MKUltra experiments conducted between 1953 and 1973, the agency searched for a psychological advantage in the Cold War.

CIA scientists theorized that psychedelic drugs (like LSD) could be used for mind control, intelligence gathering, and psychological torture. They believed that the Soviet Union might already be close to mastering mind control — and American spies and scientists wanted the same kind of power.

Ibogaine’s unique properties made it a compelling candidate.

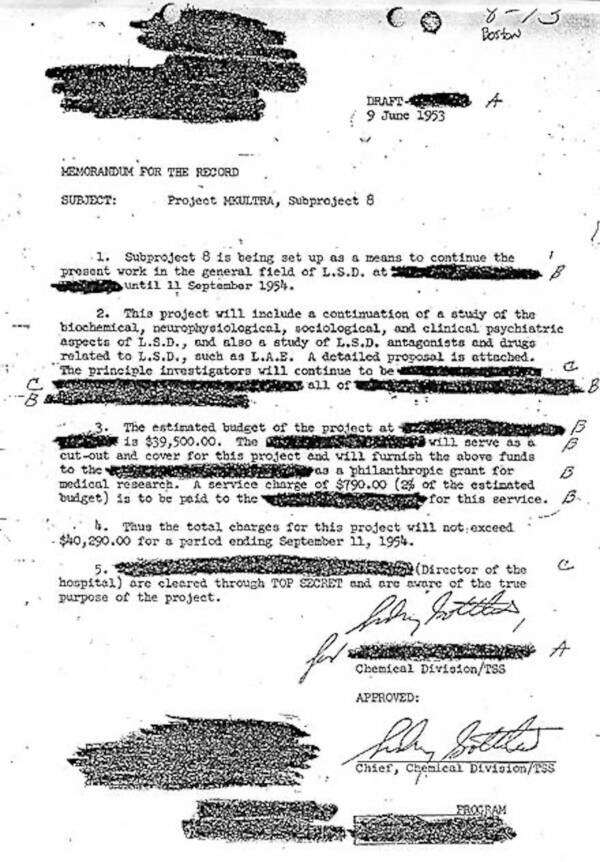

Wikimedia CommonsA redacted document from the CIA’s MKUltra experiments, which survived destruction.

When a person takes a dose of ibogaine, they go through three stages.

In the first stage, known as the “acute” phase (0-1 hours), the user’s visual and physical perception begins to change. Then, during the second stage (1-7 hours), the subject closes their eyes and experiences vivid hallucinations that are similar to a lucid dream.

During this phase, people report intense hallucinations, feelings, and changes in perception of time and space. Common hallucinations include meeting with transcendent beings and reliving past memories.

Finally, stage three (8-36 hours) involves a deep state of introspection where a person re-evaluates their life and past choices.

During these last two phases, the subject is believed to be more “pliable” and easier to influence, which may explain why the CIA allegedly thought it could be used for mind control and other psychological techniques.

Whatever the case, we’ll never know for sure since most of the MKUltra documents were either destroyed or redacted.

Howard Lotsof Discovers A New Use For Ibogaine

YouTubeIn the 1960s, Howard Lotsof discovered that ibogaine could change a heroin addict’s life.

MKUltra rumors aside, ibogaine’s true shining moment came in 1962, when a 19-year-old heroin addict named Howard Lotsof accidentally discovered that ibogaine could save people — a lot of people.

Lotsof, a New Yorker, took the drug recreationally with six of his friends after hearing of its psychedelic properties. After enjoying his trip, Lotsof noticed that his cravings for heroin had subsided.

“The next thing I knew,” Lotsof told The New York Times, “I was straight.”

His friends agreed and also noted that they weren’t feeling withdrawal symptoms. In fact, five of Lotsof’s friends quit heroin after trying ibogaine.

This incredible discovery would go on to define Lotsof’s life. For the next five decades, he would do everything in his power to promote ibogaine’s medical use and research into its anti-addictive properties.

Wikimedia CommonsAn ibogaine molecule. This psychedelic has been the subject of research for years, but it remains controversial.

In the mid-1980s, Lotsof worked with a Belgian company to produce ibogaine in capsule form. He offered the drug to addicts in the Netherlands. Although several people agreed that it reduced their cravings, it didn’t work for everyone. And in one tragic case, a young woman died after taking it.

Undeterred, Lotsof also created a U.S. patent for the use of ibogaine in treating opioid addiction, which was awarded to him in 1985. Several more patents were approved in later years.

At one point, Lotsof even traveled to Gabon, where the president presented him the iboga plant, announcing, “This is Gabon’s gift to the world.”

Although research on ibogaine offered some promising results — lab rats appeared to lose their craving for addictive drugs — it also pinpointed some disturbing side effects. One study revealed that taking the drug destroyed brain cells in rats. Another suggested that it could cause heart problems.

A lack of money and a tangle of lawsuits stunted research into ibogaine. Eventually, the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) lost interest. “The drug doesn’t look terribly promising in terms of the risks and benefits,” said Frank Vocci, director of the NIDA’s Medications Development Division.

That said, the number of people addicted to opioids doesn’t look promising either. In 2019, over 10 million Americans abused opioids.

Miracle Cure Or Dangerous Drug?

Despite the encouraging results from Lotsof’s work, ibogaine remains controversial — and illegal in the United States. Although it seems to subdue harmful drug cravings, ibogaine can also sometimes be fatal.

The Guardian estimated that about one in 400 people who take ibogaine are at risk of death. This can be due to a variety of reasons, such as pre-existing heart conditions, seizures that happen due to withdrawal from other drugs, or the use of ibogaine while also using opioids.

Still, many believe that ibogaine’s potential merits further research. Some are angry that the NIDA appears less than enthusiastic about ibogaine — and have even alleged that the NIDA is part of a wider government conspiracy to keep people addicted to substances like heroin.

“People can make any kind of assertion that they’d like, but we are constrained by the truth,” said Vocci. “We’d love to find a cure for drug abuse. Then we could move on to something else.”

Herbert D. Kleber, the director of the division on substance abuse at the New York State Psychiatric Institute at Columbia University, agrees.

“A number of deaths have been associated with its use, especially to treat opioid withdrawal and dependence,” Kleber said.

Edward Conn, a psychotherapist in the U.K., thinks that ibogaine has been oversold as a “miracle” drug. “How many official clinics exist?” Conn asked. “None. Ask yourself why.”

However, Conn does believe that ibogaine can make a difference for certain people who are addicted to drugs. “For some, ibogaine does work,” he said. “It’s most effective for individuals who have stopped their drug-using lifestyle and are stable on low-dose methadone, and least effective on individuals still engaged in drug use.”

On March 10, 2021, the U.K. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency approved a trial to use ibogaine in the treatment of opioid addiction.

One of the partners in the trial is Deborah Mash — a former collaborator of Lotsof who has been studying the potential of ibogaine for decades. Today, she’s the CEO of DemeRx, a clinical-stage pharmaceutical development company seeking to end opioid addiction for good.

Ibogaine, she asserts, remains promising. “Not only were patients able to safely and successfully transition into sobriety, we found no evidence of additional abuse potential,” said Mash of the new trial.

Today, the quest for a cure to addiction continues — and many hope that ibogaine will prevail as a miracle.

After learning about ibogaine, read about another psychedelic drug called peyote. Then, check out the study that proves psychedelic drugs create elevated levels of consciousness.