After Ignaz Semmelweis first advocated for hand-washing to fight infection in the 1840s, doctors had him committed to an asylum. He soon died there from an infection in his hand.

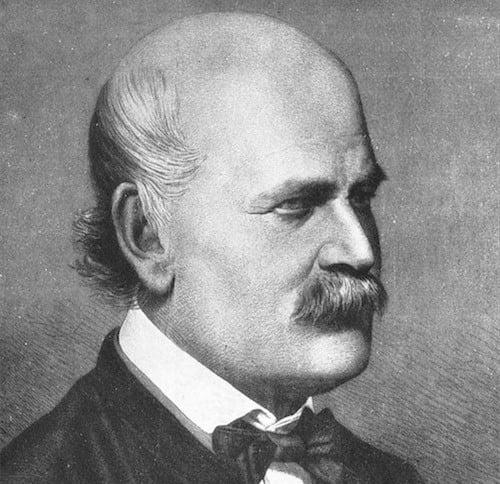

Wikimedia CommonsIgnaz Semmelweis pioneered antiseptic procedures in the mid-19th century — and it ruined his career.

Though few may know his name today, Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis changed the world in the 1840s with one simple idea that we all now take for granted: hand-washing.

Even in Semmelweis’ time, doctors — not to mention average citizens — weren’t regularly washing their hands as a way to prevent infection. And although Semmelweis was the first to advocate for hand-washing as we know it today, he wasn’t hailed as a pioneering genius.

In fact, Semmelweis was called a madman, then discredited and pushed out of medicine before finally being thrown in an asylum. He soon died there — from an infection on his hand.

Well after his death, this once-forgotten physician was finally given his due. As new diseases and full-blown pandemics continue to plague populations around the globe, the importance of Ignaz Semmelweis only becomes more and more clear.

The Young Doctor And The Horrors Of Childbed Fever

Wikimedia CommonsIgnaz Semmelweis as an adolescent. Circa 1830.

Born in what’s now Budapest, Hungary on July 1, 1818, Ignaz Semmelweis didn’t find his way into medicine right away. The son of a wealthy grocer, he decided not to join the family business and instead took up law. But after a year of study, he switched to medicine.

Once in medicine, Semmelweis failed to find a position as an internist — some say because he was Jewish — leaving him to specialize in obstetrics. In 1846, he began work in that field at the Vienna General Hospital, where he would soon change the world.

By 1847, Semmelweis became head of the maternity ward, where he had his work cut out for him. At the time, as many as one in six women at the hospital died soon after childbirth of what was known as “puerperal,” or “childbed fever.” The symptoms were always the same: The new mother developed chills and a fever, her abdomen would become agonizingly painful and bloated, and within a few short days she’d be dead, leaving the newborn motherless.

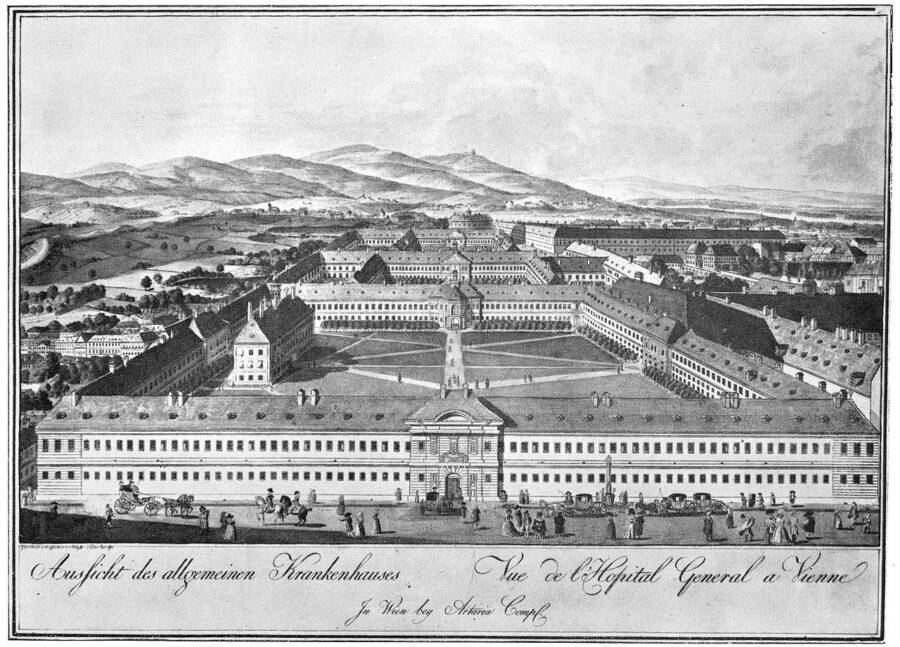

Wikimedia CommonsVienna General Hospital, where Ignaz Semmelweis worked when first pioneering modern hand-washing.

The women’s autopsies were also always the same. Doctors and medical students alike knew that when they opened the body, they would be met with a stench so strong that it caused many new students to vomit on the spot. They would then observe the swollen and inflamed uterus, ovaries, and Fallopian tubes, and pools of puss all throughout the abdominal cavity. Simply put, the women’s insides had been ravaged.

Explanations for the common and horrific deaths ranged from birthing fluid getting “backed up” in the birthing canal to “cold air getting into the vagina” to the belief that the mother’s breast milk had become rerouted away from the breast and spoiled inside the body (which is what many physicians believed the puss to have been).

Others believed it was caused by noxious particles in the air, and others still just thought it had to do with the natural constitution of the mothers — some women would get the fever, and others simply wouldn’t, and there wasn’t much any doctor could do about it. But Ignaz Semmelweis had other ideas.

How Ignaz Semmelweis Pioneered Hand-Washing

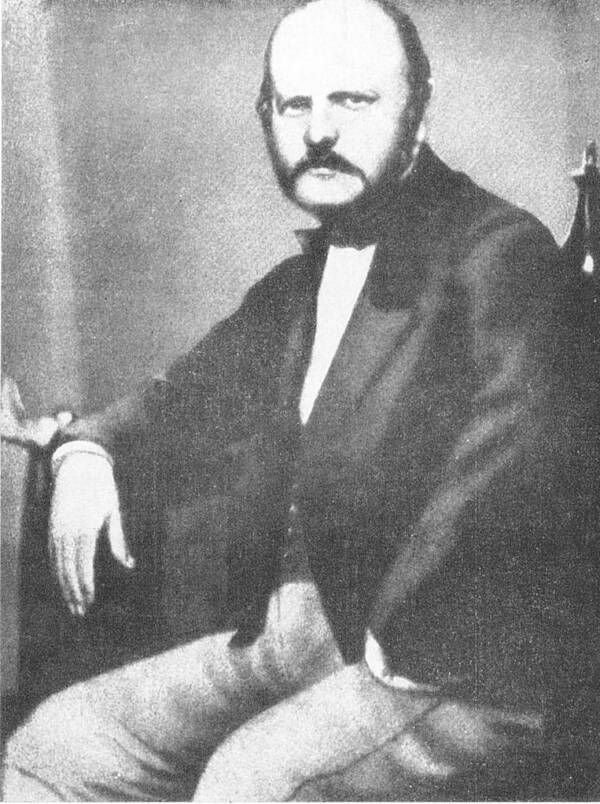

Wikimedia CommonsIgnaz Semmelweis quickly realized that childbed fever was exacerbated by tainted hands, which, if washed, could save lives.

As the head of the hospitals’ two maternity wards — one in which only midwives delivered babies, and one in which doctors and medical students worked — Ignaz Semmelweis noticed that the death rate from childbed fever was as much as four times higher in the latter. Women became aware that the midwives’ clinic was much safer than the doctors’ and begged to be admitted to the first, with some even opting for street birth to avoid being seen by the doctors.

Why would trained doctors account for so many more deaths than midwives? Could there actually be a connection, Semmelweis wondered, between the doctors and medical students (who often went straight from cadaver dissection to the maternity ward) and the horrific deaths of these women?

After studying the fever rates of both wards, as well as those of the population at large, Semmelweis was certain of one thing: The rate of death from childbed fever in the doctor-run hospital ward was not only significantly higher than it was in the other maternity ward run by midwives but it was also higher than the average for the entire city of Vienna, including home births and unassisted beggar women. It was literally safer to give birth to your child alone in an alleyway than to have it delivered by one of the best-trained doctors in the country.

And this is when Ignaz Semmelweis hit upon his historic idea: Perhaps something was being transmitted from the autopsied corpses to the women giving birth. Often times a medical student would dissect a woman who had died of childbed fever, and — with his same, unwashed hands — report to the maternity ward minutes later to deliver babies.

Semmelweis speculated that potentially deadly particles were transferred from one location to another on the very hands of the doctors and medical students there to help people and save lives. This was, in essence, germ theory almost 20 years before it was popularized by the famous Louis Pasteur.

Semmelweis thus forced all of the doctors and students on his staff to sanitize their hands with chlorine and lime before entering the maternity ward, and the death rate of childbed fever was reduced to 1.2 percent within a year — almost exactly equal to that of the ward run by the midwives. Semmelweis’ idea had proved to be an enormous success.

The Medical Community Strikes Back

Wikimedia CommonsProfessors of the Vienna General Hospital medical school in 1853.

However, despite the extremely compelling empirical evidence, the medical community widely disregarded or actively disparaged Ignaz Semmelweis’ theory.

Many doctors were simply unwillingly to even entertain the idea that they could be hurting their own patients. Others felt that as gentlemanly doctors, their hands couldn’t possibly be dirty. Meanwhile, others simply weren’t ready for an idea that flew in the face of all they’d been taught and practiced their whole careers.

With no germ theory yet on paper to back up this new idea, the medical community pushed back against it. Semmelweis was harassed, rejected by or criticized in medical journals, and was gone from the hospital within a few short years.

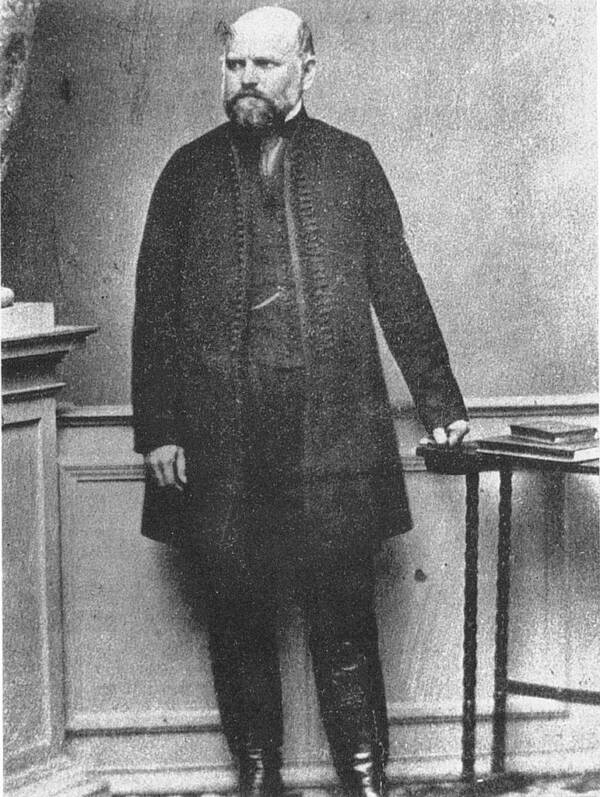

Wikimedia CommonsIgnaz Semmelweis in 1863 in what’s believed to be one of his last-known photos.

His career never recovered and he eventually began to show signs of mental illness. He slowly descended into depression and anxiety, writing open letters meant to convince his colleagues and turning nearly every conversation in his private life toward infection control.

By the mid-1860s, Semmelweis’s behavior was completely unhinged and even his family could neither understand nor tolerate him. In 1865, Semmelweis’ doctor János Balassa had him committed to an asylum, even employing another colleague to lure Semmelweis there under the ruse that they’d be simply touring the facility together as professionals.

Semmelweis saw through the trick and soon struggled with the guards. They beat him severely before putting him in a straitjacket and tossing him in a darkened cell.

Just two weeks later, on August 13, Semmelweis died at age 47 from a gangrenous infection on his right hand believed to be a result of the struggle with the guards.

The Historic Legacy Of Ignaz Semmelweis

Even after his death, Ignaz Semmelweis never got the credit he deserved. Once germ theory became established and hand-washing became more standard, later proponents of such notions and practices simply soaked up any recognition that Semmelweis would have ever gotten.

But with enough time and historical scholarship on his life, Semmelweis’ story slowly came to light. He’s even now the namesake for the “Semmelweis reflex,” which describes the human tendency to reject or ignore new evidence that contradicts established norms or beliefs.

Moreover, of course, Semmelweis’ hand-washing advice has long been considered life-saving common sense. In fact, hand-washing has become so routine that you may hardly think about it at all even while doing it.

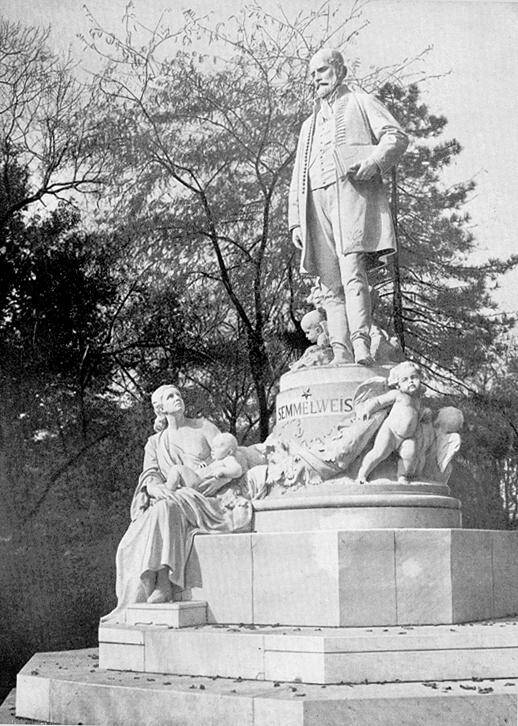

Wikimedia CommonsA 1904 statue of Ignaz Semmelweis in his native Hungary — a rare instance of recognition for him in his own century.

We may now only think about it in times of unusual medical emergency, such as a pandemic. When COVID-19, for example, began to spread around the world in early 2020, world leaders urged everyone to wash their hands rigorously and frequently.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention listed hand-washing as the most important thing citizens could do to avoid contracting COVID-19. The World Health Organization, UNICEF, and many other organizations gave the same advice.

And while this advice may seem obvious, it certainly wasn’t obvious when Ignaz Semmelweis became the first to propose it.

In March 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic raged around the globe, Google dedicated a Doodle to Semmelweis, calling him “the father of infection control.” Perhaps, after nearly two centuries, Ignaz Semmelweis finally got his due.

After this look at Ignaz Semmelweis, read up on another medical pioneer who never got the credit they deserved for their greatest advancement, Alice Ball. Then, see inside some of the 19th-century asylums like that which housed Semmelweis just before his death.