When Alice Ball made the discovery that brought leprosy patients back from certain death, she wasn't just young — she was also a black woman in Jim Crow-era America.

In 1915, a young black chemist named Alice Ball revolutionized the treatment for leprosy, a painful and stigmatized disease. Decades before the development of antibiotics, Ball devised a method for treating lepers that allowed them to live without being ostracized or isolated.

But how did Alice Ball, a black woman in Jim Crow-era America, become such a pioneer in science?

Alice Ball Was Born To Break Barriers

On July 24, 1892, Laura and James Ball welcomed their first daughter, Alice Ball, to their family.

The Balls lived in Seattle’s Central District where James worked as a lawyer and Laura as a photographer. Alice Ball’s grandfather was also a pioneer as one of the first photographers to use the daguerreotype method which prints images on metal plates.

During her childhood, Ball lived in Honolulu for a few years before returning to Seattle where she graduated from Seattle High School in 1910.

After receiving top marks, Ball enrolled at the University of Washington and studied pharmacy and chemistry. She earned a degree in pharmaceutical chemistry and returned to Hawaii for a master’s degree in chemistry at the College of Hawaii, now the University of Hawaii.

She specialized in isolating the active components in the kava root, a plant native to the Pacific Islands, and while working on her master’s, Ball published two articles in the world’s most prestigious chemistry journal.

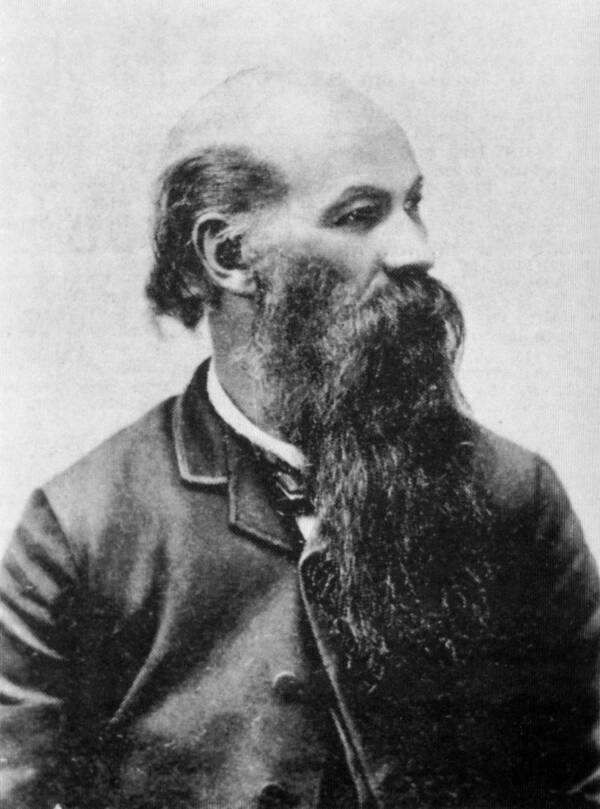

Wikimedia CommonsJames Ball, Alice Ball’s grandfather, was a pioneer in daguerreotype photography.

Upon her graduation in 1915, Ball became the first woman and the first black student to earn a master’s degree in chemistry from the College of Hawaii.

The college then offered Ball a position as a chemistry instructor and she became the first woman to teach chemistry at the college – at just 23 years old.

In addition to her teaching, Ball continued working on plant biochemistry in the laboratory. Her work was quickly recognized by Dr. Harry T. Hollmann, the director of the Kalihi leprosy clinic, and he contacted Ball for help in finding a better treatment for the disease.

Traditional leprosy treatments relied on oil from the chaulmoogra tree that would be applied as a topical ointment, but this was not all that effective. Hollman wanted Ball to isolate the oil and create an injectable treatment instead.

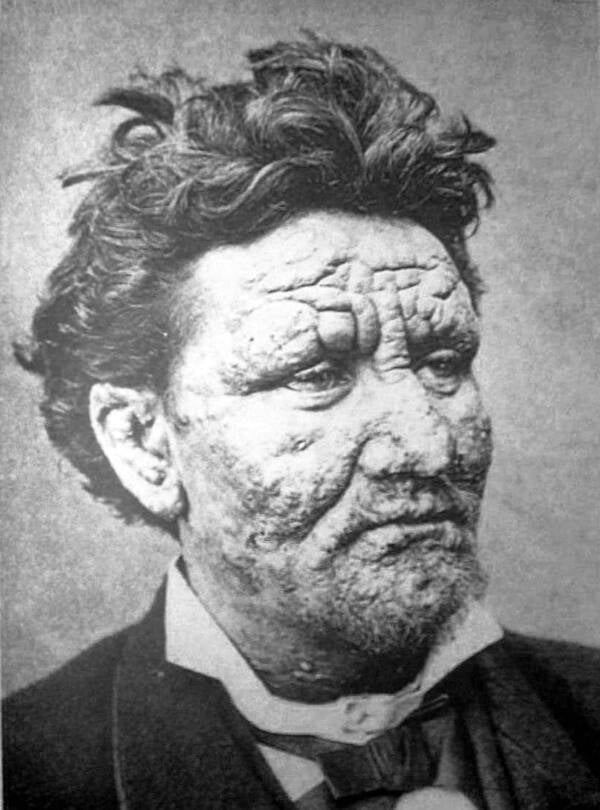

Wikimedia CommonsAn 1886 photograph of Arran Reeve, a man suffering from leprosy.

Within a year, Ball did just that.

It would be the most important leprosy treatment before the advent of antibiotics.

Combatting A Death Sentence

Prior to Ball’s innovation, leprosy — also known as Hansen’s Disease — was considered an incurable disease with no effective treatments.

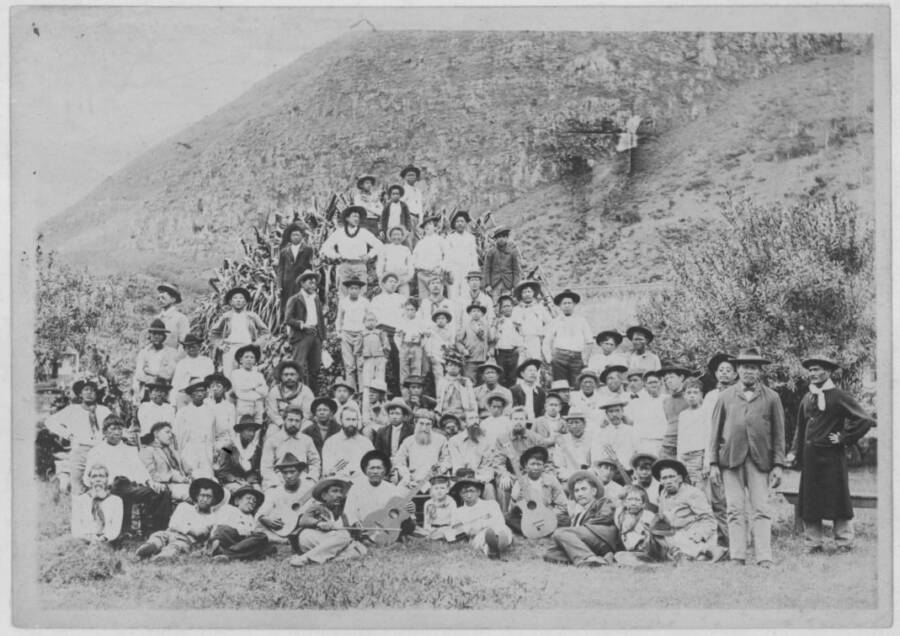

The disease also carried a heavy stigma. Lepers were isolated or shuttered away from their families at special colonies where they couldn’t infect others. There was one such colony on the Hawaiian island of Molokai which housed 8,000 residents over the course of its existence. Indeed, the government even declared all the lepers there legally dead.

Hawaii State ArchivesIn 1905, the Kalaupapa leper colony housed 750 people.

James Harnisch, head of the Hansen’s Disease Clinic at the Harborview Medical Center, recently said that prior to the early 20th century, “There was no treatment at that point in time at all, so it was a matter of just offering care while you’re watching the disease progress to destroy the face, destroy the hands, the arms. It was a very sad situation.”

In 1873, scientists first identified the bacteria that caused leprosy. Yet the painful disease still had few effective treatments. A Chinese and Indian folk remedy involved oil from the chaulmoogra tree. But with no way to safely inject the oil, patients who tried this treatment were beset with painful side effects.

That is until Alice Ball developed her new method.

The Groundbreaking Ball Method Offered New Life To Lepers

In the lab, Alice Ball first successfully isolated the active ingredient in chaulmoogra oil.

Hoapili/Wikimedia CommonsThe Molokai leper colony in 1922. It was known as the “Land of the Living Dead.”

“People were struggling with what do you do with this oil which, if you let it sit, it just hardens into, like, lard,” explained Paul Wermager, head of the science library at the University of Hawaii. “But using alcohol you make it into what’s called an ethyl ester. Then it becomes water-soluble, and that was the breakthrough that she made.”

Ball created history’s first effective and pain-relieving treatment for leprosy, appropriately named the “Ball Method.”

At Molokai’s leper colony, the “Ball Method” gave patients formerly seen as hopeless a new lease on life. The treatment eliminated their symptoms and proved so effective that leprosy patients around the world were discharged from their isolation in hospitals and sent home.

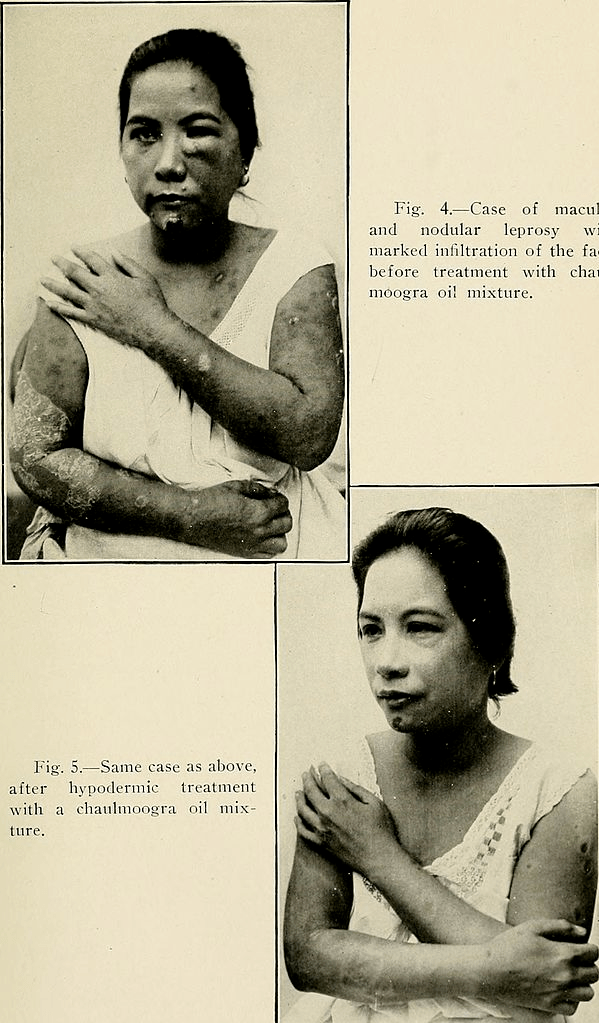

“People who did finally get the injections did show remarkable improvements,” Wermager continued. “I’ve found photographs, and they’re just startling. The person looks like, really, a different person.”

Ball’s Untimely Death And Legacy

Wikimedia CommonsA woman suffering from leprosy before and after she received the injection Ball developed, 1919.

In a preparatory lecture during World War I, Ball was showing her students how to properly use a gas mask. But an accident during the presentation exposed her to chlorine gas. As the Honolulu Pacific Commercial Advertiser explained, “While instructing her class in September 1916, Miss Ball suffered from chlorine poisoning.”

Ball became seriously ill and returned to Seattle where she died within months at the age of 24.

Even in death, Alice Ball faced barriers in her scientific career when Dr. Arthur Dean, the president of the College of Hawaii, took credit for her research into chaulmoogra oil – and he even renamed her discovery the “Dean Method.”

Fortunately, Dr. Hollmann, who first turned to Ball for help in treating leprosy, published a paper that named her as the true inventor of the method.

“You have to understand, she was doing this before women had the right to vote,” explained Dr. Harnisch. “This is amazing. And again, she was an African American woman. Phenomenal that she could get this far.”

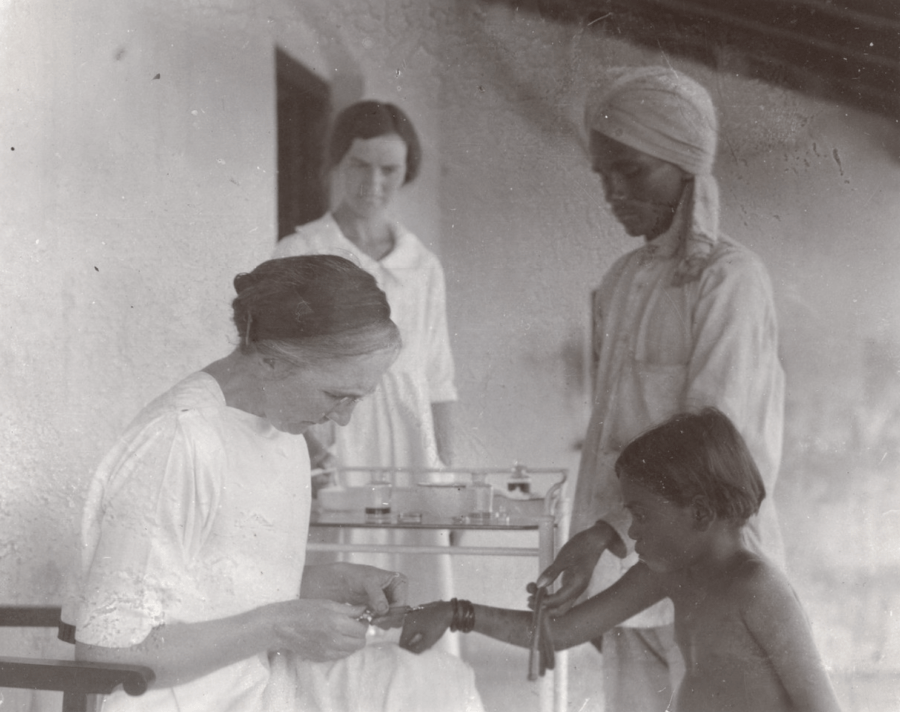

G.M. Kerr/Wellcome ImagesDr. Isabell Kerr treating a leprosy patient in 1926.

Recently, Ball’s groundbreaking career has finally received the attention it deserves. In 2017, Paul Wermager established a scholarship opportunity at the University of Hawaii to recognize her. He explained:

“Not only did she overcome the racial and gender barriers of her time to become one of the very few African American women to earn a master’s degree in chemistry, [but she] also developed the first useful treatment for Hansen’s disease.”

Wermager adds, “Her amazing life was cut too short at the age of 24. Who knows what other marvelous work she could have accomplished had she lived.”

Ball now holds a posthumous Medal of Distinction from the University of Hawaii and a plaque on campus reminds students and visitors of Ball’s achievements. Hawaii recognizes February 29th as Alice Ball Day.

Alice Ball wasn’t the only woman in science ignored by history. Learn about the female scientists who fought for their recognition. Then, check out these startling photographs of segregation in America.