Ilse Koch may not be as famous as the Holocaust's ringleaders, but she was every bit as evil.

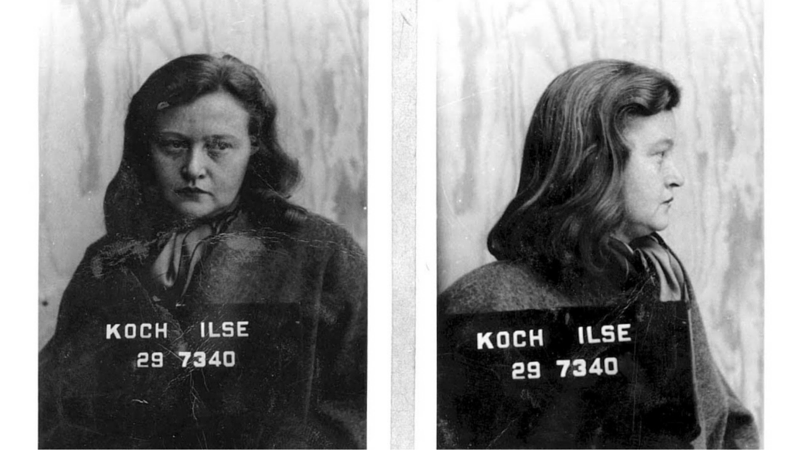

Wikimedia CommonsIlse Koch, popularly known as the “The Bitch of Buchenwald.”

The stories of Gisella Perl and Stanislawa Leszczyńska highlight one vital aspect of human nature: Our ability to persevere and care for others in even the most harrowing and cruel of circumstances.

But the Holocaust also presented many opportunities for humanity’s terrible dark side to run wild, as well. While Adolf Hitler, Josef Mengele, and Heinrich Himmler are rightly remembered as its figureheads, there were others just as villainous, but their names didn’t quite make the history books.

One of these individuals was Ilse Koch, whose sadism and barbarism would lead to her to receive the nickname “The Bitch of Buchenwald.”

Sydney Morning HeraldA young Ilse Koch.

Ilse Koch, born Margarete Ilse Köhler, was born in Dresden, Germany on September 22, 1906, to a factory foreman. Her childhood was completely unremarkable: Teachers noted her as being polite and happy, and at age 15 Koch entered accounting school, one of just a few educational opportunities for women at the time.

She began working as a bookkeeping clerk at a time when Germany’s economy was struggling to rebuild itself after World War I, and in the early 1930s, she and many of her friends joined the Nazi Party. The party and Hitler’s ideology, was attractive to Germans first and foremost because it seemed to offer solutions to the myriad of difficulties the country faced after losing the Great War.

In the beginning, the Nazis focused mainly on turning the German people against democracy — specifically, the Weimar Republic’s first politicians — which they felt was at the root of why they had lost the war.

Hitler was a compelling speaker, and his promise to abolish the deeply unpopular Treaty of Versailles — which demilitarized part of the country and forced it to pay massive, unaffordable reparations while trying to recover from the calamities of war — appealed to many Germans who were struggling both with identity and making ends meet.

Koch, who was already well aware of the penurious economic climate, likely felt that the Nazi Party would restore and perhaps even bolster the fraught economy. In any case, it was her involvement in the party that introduced her to her future husband, Karl Otto Koch. They were married in 1936.

The following year, Karl was made Commandant of the Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar, Germany. It was one of the first and largest of the camps during the Holocaust, opened shortly after Dachau. The iron gate that led into the camp read Jedem das Seine, which literally meant “to each his own,” but was intended as a message to the prisoners: “Everyone gets what he deserves.”

Ilse Koch jumped at the opportunity to become involved in her husband’s work, and over the next few years gained a reputation for being one of the most feared Nazis at Buchenwald. Her first order of business had been to use money stolen from prisoners to construct a $62,500 (around $1 million in today’s money) indoor sports arena where she could ride her horses.

Koch would often take this pastime outside the arena and into the camp itself, where she would taunt prisoners until they looked at her — at which point she would whip them. Survivors of the camp recalled during her trial for war crimes that she always seemed particularly excited about sending children to the gas chamber.

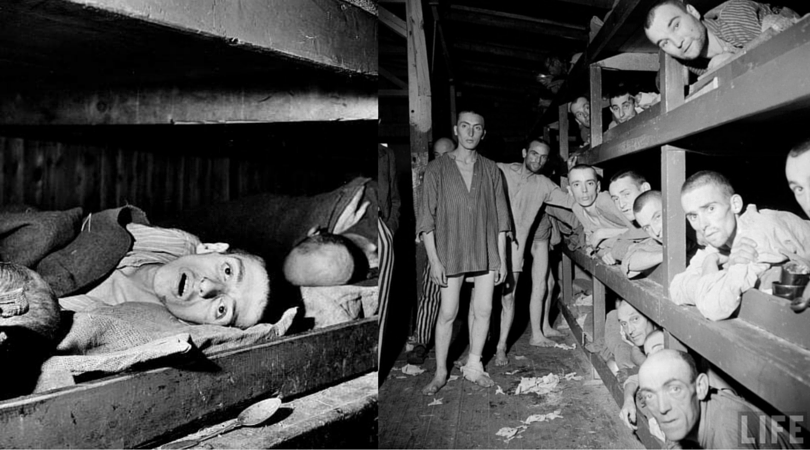

Margaret Bourke-White/Time & Life Pictures/Getty ImagesLife inside a concentration camp.

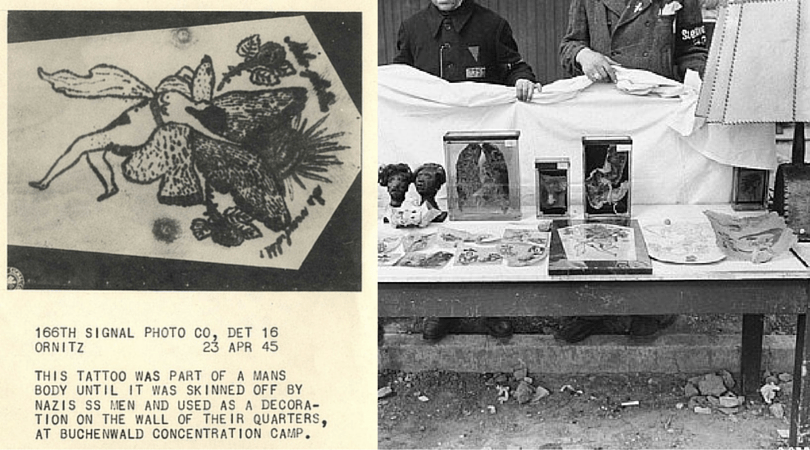

Her other hobby, which would later become a major point of contention during the Nuremberg Trials, was her collection of lampshades, book covers, and gloves, said to have been made from human skin.

Witnesses later recalled that Ilse Koch often took her horseback rides through the camps to scout out prisoners who had distinctive tattoos. The prisoner would be stripped of his or her skin before being incinerated, and Koch allegedly kept the skin on display in her home with the Commandant. These artifacts were recovered after the camp’s liberation and served as key evidence during her trial.

She and her husband were arrested on August 24, 1943 at Buchenwald on charges of embezzlement and murder of prisoners. Despite the Nazis’ mass murder of prisoners and their tortuous medical experiments, even they did not find the Kochs’ methods of torment suitable to their ideology — although mainly because any punishments had to be cleared by the main office in Oranienburg and the Kochs were acting of their own accord.

It was also alleged that Commandant Koch had ordered the execution of the orderly who had diagnosed him with and treated him for syphilis so that the secret would never be revealed. Frau Koch, in the meantime, had taken several lovers at Buchenwald, and it was widely accepted that her marriage to the Commandant had been an open one.

While Commandant Koch was sentenced to death just a week before Buchenwald was liberated while Frau Koch was acquitted, mostly due to lack of evidence — specifically, that investigators could not prove the lampshades and other items were actually made from human skin. For her part, Ilse insisted they were made of goatskin.

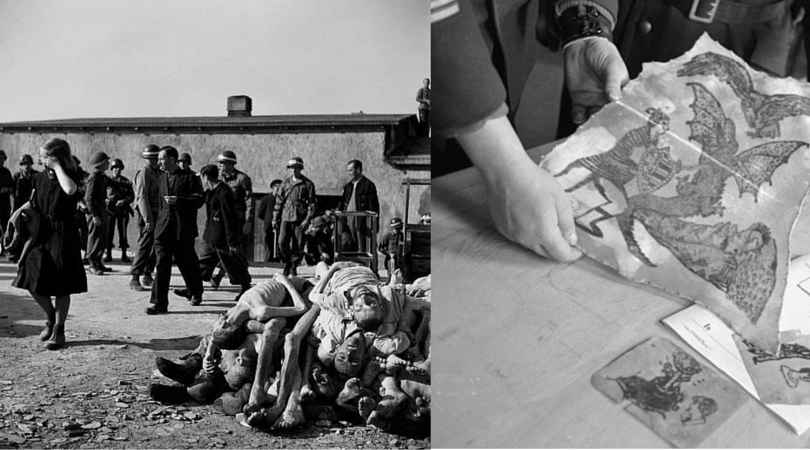

Getty ImagesGermans visit Buchenwald after its liberation.

Following the camp’s liberation in 1945, word began to travel about Frau Koch’s sadistic involvement, as survivors recalled her in interviews. The public pressured the court to bring her to trial again.

Ilse Koch was brought before the General Military Government Court for the Trial of War Criminals in 1947. On the stand, she announced that she was eight months pregnant, which came as a shock for two reasons. Firstly, she had had no contact with any men except for American interrogators — many of whom were Jewish — before her trial, and secondly, she was 41 years old.

Despite her pregnancy, she was charged with “participating in a criminal plan for aiding, abetting and participating in the murders at Buchenwald” and sentenced to life in prison for “violation of the laws and customs of war.”

She had birthed one son with Commandant Koch before their arrest, and the second child, whose father was unknown, was born while she was imprisoned. Both of her children went to foster homes.

Two years after her conviction, her sentence was reduced to four years by General Lucius D. Clay, the interim military governor of the American Zone in Germany. According to Clay, the reduction came since “there was no convincing evidence that she had selected inmates for extermination in order to secure tattooed skins, or that she possessed any articles made of human skin.”

The court maintained that perhaps the items had been made of goatskin after all, and she was released. However, the General stated:

“I hold no sympathy for Ilse Koch. She was a woman of depraved character and ill repute. She had done many things reprehensible and punishable, undoubtedly, under German law. We were not trying her for those things. We were trying her as a war criminal on specific charges.”

Wikimedia CommonsIlse Koch at her trial.

The public was aghast at her release, and she was rearrested shortly thereafter. Throughout her second trial, which began in 1950, she collapsed frequently and had to be removed from the court. Over 250 witnesses were called throughout the trial — including 50 for the defense.

Four of the witnesses testified that they had seen Koch selecting prisoners specifically for their tattoos, or that they had seen or been involved in the manufacturing of the human-skin lampshades. As had happened due to lack of evidence before, this charge was eventually dropped.

On January 15, 1951, the Court gave its verdict in a 111-page decision. Koch was not present. She was convicted of “charges of incitement to murder, incitement to attempted murder, and incitement to the crime of committing grievous bodily harm,” and again sentenced to life imprisonment with permanent forfeiture of any civil rights.

During her time in prison, she petitioned for appeals several times but was always dismissed. She even protested to the International Human Rights Commission, but was rejected.

While in prison, her son Uwe, who had been conceived during her imprisonment at Dachau, discovered that she was his mother. He came to visit her in prison often over the next several years at Aichach, where she served her life sentence.

On September 1, 1967, Ilse Koch committed suicide in prison. The next day, Uwe arrived for their visit and was shocked to find that she had died. She was buried in an unmarked, untended grave at the prison’s cemetery.

Wikimedia CommonsHuman remains and images of tattoos from Buchenwald.

The lampshades have never been recovered, and many historians seem to doubt their existence. However, a writer — also Jewish — named Mark Jacobson has made it his mission to authenticate their existence. His grim quest began when a man named Skip Hendersen purchased a lampshade touted as a Nazi relic at a post-Hurricane Katrina garage sale.

Hendersen sent it to Jacobson, who even traveled with it to Buchenwald, but has been unable to definitively determine its origin. DNA testing conducted initially revealed that the lampshade was likely made of human skin, but later testing revealed that the shade is more likely made of cowskin. It seems, in the end, that this was one secret the Bitch of Buchenwald took with her to the grave.

After learning about Ilse Koch, read about Ravensbruck, the women’s concentration camp.