These are the last thing you would expect from the author of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses.

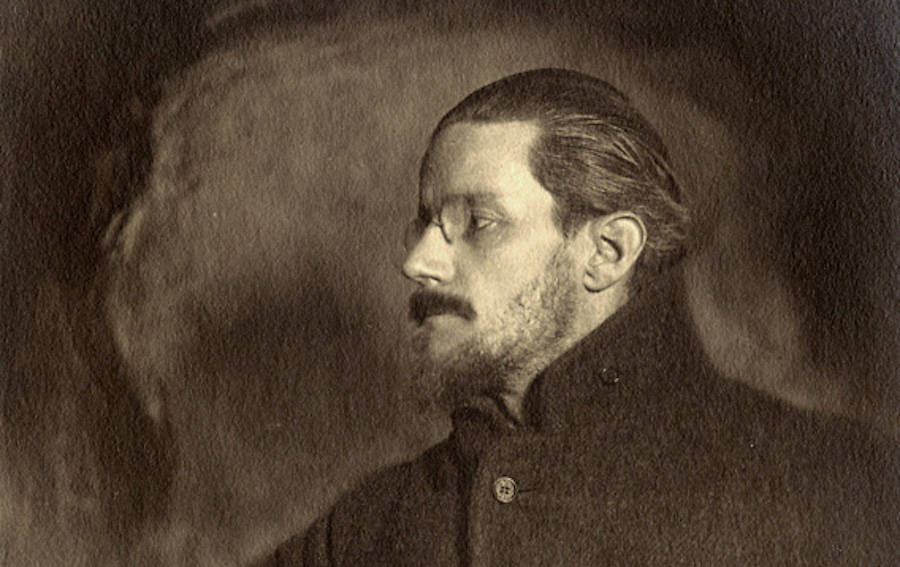

Cornell Joyce Collection/Wikimedia CommonsJames Joyce

“You had an arse full of farts that night, darling, and I fucked them out of you, big fat fellows, long windy ones, quick little merry cracks and a lot of tiny little naughty farties ending in a long gush from your hole. It is wonderful to fuck a farting woman when every fuck drives one out of her. I think I would know Nora’s fart anywhere. I think I could pick hers out in a roomful of farting women. It is a rather girlish noise not like the wet windy fart which I imagine fat wives have. It is sudden and dry and dirty like what a bold girl would let off in fun in a school dormitory at night. I hope Nora will let off no end of her farts in my face so that I may know their smell also.”

At first glance, that doesn’t seem like the sort of thing one of the greatest writers of all time would produce, does it? But that passage actually came from the pen of James Joyce in a letter addressed to his wife Nora Barnacle.

Joyce was an Irish writer in the early 20th century, and his modernist novels like Ulysses and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man are often cited as some of the best literary works of all time. And if it’s strange to think of such a respected novelist penning graphic passages about farts to his wife, Joyce seems to have agreed. In another letter, he wrote:

“Today I stopped short often in the street with an exclamation whenever I thought of the letters I wrote you last night and the night before. They must read awful in the cold light of day. Perhaps their coarseness has disgusted you… I suppose the wild filth and obscenity of my reply went beyond all bounds of modesty.”

But in many ways, Joyce and his wife had a relationship that was unusually physically passionate.

Nora Barnacle, the wife of James Joyce with their children.

James Joyce and Nora Barnacle met on the streets of Dublin in 1904. Joyce was immediately struck by Barnacle, or at least what he could see of her since he was famously near-sighted and wasn’t wearing his glasses at the time. Joyce asked Barnacle on a date, only to be stood up.

“I may be blind,” he wrote to her, “I looked for a long time at a head of reddish-brown hair and decided it was not yours. I went home quite dejected. I would like to make an appointment… If you have not forgotten me.”

James Joyce and Nora Barnacle eventually met again for a walk to the Ringsend area of Dublin, and the date seems to have gone very well according to how Joyce later described in a letter:

“It was you yourself, you naughty shameless girl who first led the way. It was not I who first touched you long ago down at Ringsend. It was you who slid your hand down inside my trousers and pulled my shirt softly aside and touched my prick with your long tickling fingers, and gradually took it all, fat and stiff as it was, into your hand and frigged me slowly until I came off through your fingers, all the time bending over me and gazing at me out of your quiet saintlike eyes.”

By the end of the year, the couple had moved together to Trieste in what was then Austria-Hungary. Over the next few decades, Joyce shuttled from city to city trying to make a living as a struggling artist. Nora, meanwhile, remained in Trieste raising their children. It seems to have been Nora Barnacle herself who first began the erotic correspondence with her husband, perhaps hoping to keep him from straying into the arms of prostitutes.

Joyce himself was a mild-mannered man who felt uncomfortable using coarse language in public. But a different side of the writer emerges in the passionate letters to his wife.

“As you know, dearest, I never use obscene phrases in speaking. You have never heard me, have you, utter an unfit word before others. When men tell in my presence here filthy or lecherous stories I hardly smile,” he wrote to Nora. “Yet you seem to turn me into a beast.”

The letters also offer a very private glance into Joyce’s particular tastes when it came to sex, which seem to have run to the scatological at times.

“My sweet little whorish Nora. I did as you told me, you dirty little girl, and pulled myself off twice when I read your letter. I am delighted to see that you do like being fucked arseways.”

Other letters make the connection even clearer:

“Fuck me if you can squatting in the closet, with your clothes up, grunting like a young sow doing her dung, and a big fat dirty snaking thing coming slowly out of your backside… Fuck me on the stairs in the dark, like a nursery-maid fucking her soldier, unbuttoning his trousers gently and slipping her hand into his fly and fiddling with his shirt and feeling it getting wet and then pulling it gently up and fiddling with his two bursting balls and at last pulling out boldly the mickey she loves to handle and frigging it for him softly, murmuring into his ear dirty words and dirty stories that other girls told her and dirty things she said, and all the time pissing her drawers with pleasure and letting off soft warm quiet little farts.”

We can get a sense of what Nora was writing back from references Joyce made to her letters in his own. They seem to have been just as erotic as his own.

“You say when I go back you will suck me off and you want me to lick your cunt, you little depraved blackguard,” he wrote in one letter. In another he said,

“Goodnight, my little farting Nora, my dirty little fuckbird! There is one lovely word, darling, you have underlined to make me pull myself off better. Write me more about that and yourself, sweetly, dirtier, dirtier.”

James Joyce’s letters were eventually sold by his brother Stanislaus’ widow to Cornell University in 1957, which is the only reason we know of them. Nora’s replies haven’t come to light. They may yet be sitting in a box or pressed between the pages of a book somewhere.

1934 Paris, France. James Joyce, pictured with his family in their Paris home. Mr. Joyce and his wife are standing. Seated are Mr. and Mrs. George Joyce, the author’s son and daughter-in-law, with their child, Stephen James Joyce, between them.

The letters we do have aren’t just a titillating glance into Joyce’s sex life. Taken with his other letters to his wife, they give us an idea of the sort of personal changes Joyce was going through.

These early letters are full of eroticism, but as Joyce experts have pointed out, there’s a sudden turn in the content of the letters in Joyce’s middle age. No longer do we see the same kind of passion. Instead, Joyce’s letters speak of marital difficulties caused by his financial position and a shift toward a more dutiful kind of love for his wife.

Joyce died in 1941 at just 58. His letters toward the end of his life suggest he was going through the same sort of transformation that everyone does as they see the end coming. For people interested in his life, the letters offer a unique perspective.

They’re a look at the most intimate details of his life, and they help us see a famous artist as a real person, embarrassing fetishes and all.

After reading the salicious letters of James Joyce to his wife Nora Barnacle, read Benjamin Franklin’s thoughts of farting. Then learn about wife-selling – the 19th century alternative to divorce.