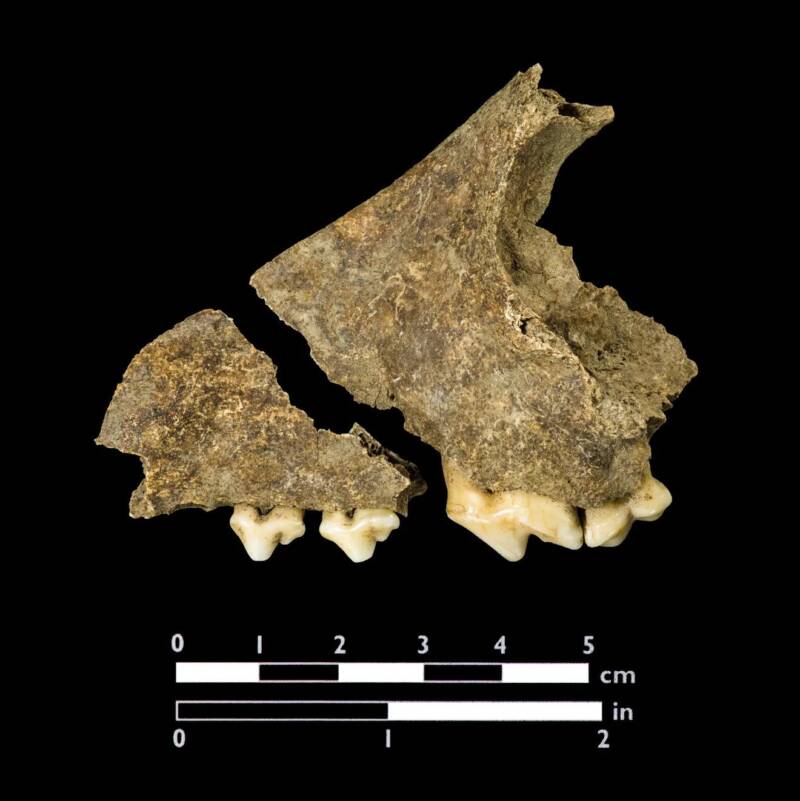

Because the bones have cut marks, researchers suggest that the colonists ate the dogs during a period of severe famine.

Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation (Preservation Virginia)Researchers were able to extract DNA from some of the dogs’ teeth which suggests they were indigenous animals.

They say dogs are man’s best friend. But for starving colonists in 17th-century Jamestown, indigenous canines may have been dinner.

Dog bones found at Jamestown, studied by University of Iowa Ph.D. candidate Ariane Thomas, bear cut marks that suggest that they were consumed by colonists. What’s more, Thomas was able to isolate DNA in some of the dogs’ teeth that matches a dog buried at the site of an indigenous settlement, some 20 miles away.

According to the Washington Post, Thomas made the find by accident. She was interested in learning more about how European dogs came to replace indigenous dogs, canines who had migrated to North America thousands of years earlier alongside human migrants from Asia.

When Thomas learned that Jamestown Rediscovery had colonial dog bones in its collection, she visited the site and conducted DNA tests on six canine remains. Just two offered up DNA, and provided a compelling genetic link to some of the continent’s most ancient dog species.

“Based on archaeological research and historical documents, Jamestown was a place of interaction between European colonists and the Indigenous communities [living in the region],” Thomas told Live Science at the time of the discovery. “It is likely that these dogs accompanied Indigenous people while those individuals were visiting — or perhaps living in — Jamestown.”

It was only recently that she was able to extract DNA from a third set of bones — which provided a stunning match to a dog buried alongside others at an indigenous settlement called the Hatch site, according to USA Today.

“That’s new news,” Michael Lavin, director of collections at Jamestown Rediscovery, told the Washington Post.

Indeed, the DNA match provides an especially compelling confirmation of the dogs’ indigenous lineage. But what happened to the doomed dogs at Jamestown?

Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation (Preservation Virginia)Some of the dog teeth from Jamestown studied by Thomas.

Lavin told the Washington Post that the dog bones had cut marks which suggested that the colonists killed and ate them. This makes sense, as scores of Jamestown colonists starved to death in the winter of 1609-1610. USA Today reports that of the 340-350 colonists, just 60 survived the winter.

“They resorted to eating some of the taboo foods, so their horses, dogs, cats, rats, and even humans,” Lavin explained to USA Today. “After (humans) died, they resorted to survival cannibalism. This dog story is just further evidence of that horrible winter.”

Researchers noted that such behavior was unusual, however, and prompted by a period of great stress.

As for how the dogs came to live at Jamestown, researchers admit that it’s unclear. They could have been gifted to the colonists by indigenous people or traded for other items and goods.

“Both are possible,” Thomas told USA Today. “It is also possible that the dogs were around humans, although not necessarily regarded as pets as we would consider them today. The dogs may have traveled to Jamestown with Native Virginians and stayed there without direct human intention or interference.”

In any case, the discovery of the dogs’ DNA and the evidence that they were eaten both provide fascinating insights into the lives of indigenous dogs. According to the Washington Post, they were quite different from the European dogs who eventually replaced them.

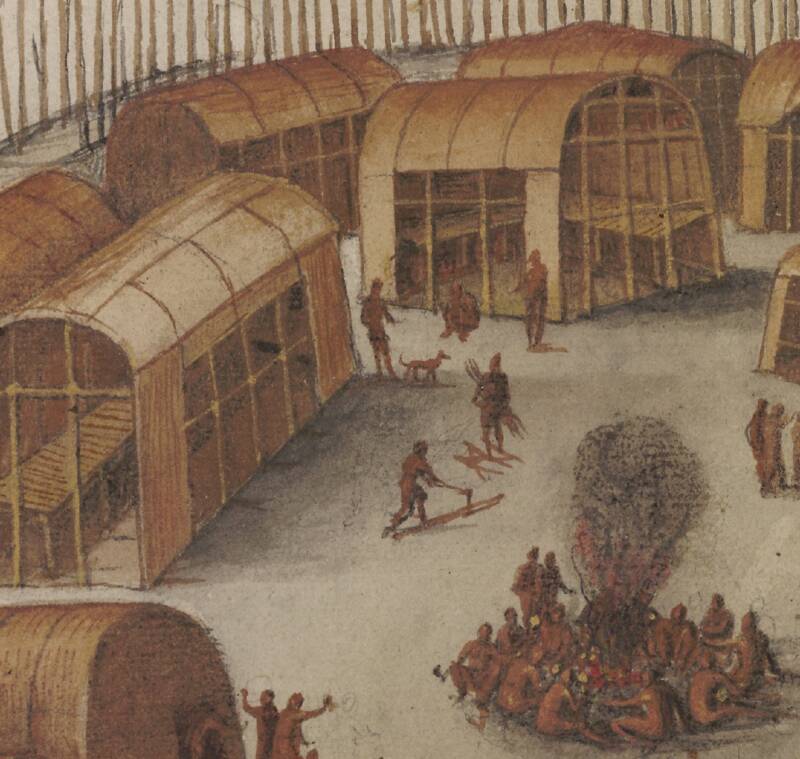

British MuseumA 16th-century painting by English colonist John White, which appears to depict a dog living among indigenous people.

These dogs resembled wolves or foxes and, unlike modern-day dogs, didn’t bark — though they were known to howl. Native people appeared to use dogs for a multitude of purposes, from companionship to animal sacrifices. They were sometimes buried alongside humans, and tribes in the Pacific Northwest were known to harvest their fur.

Following the colonization of North America, however, indigenous dogs were rapidly replaced by European dogs. As such, discoveries like the one at Jamestown offer a fascinating look at how these indigenous dogs lived among humans — and died by their hand — hundreds of years ago.

After reading about the indigenous dog bones studied at Jamestown, see how Jamestown colonists turned to cannibalism during the desperate era of “Starving Time.” Or, go inside the true story of Pochantas, the native woman who played a crucial role in Jamestown’s history and whose story was later told — mostly inaccurately — by Disney.