The Japanese-American internment camps serve as a stark reminder of what angry, frightened Americans are capable of.

In 1941, more than 100,000 people of Japanese ancestry – two-thirds of whom were natural-born citizens of the United States – lived and worked in the West Coast states. In July of that year, the U.S. government imposed sanctions on the Empire of Japan aimed at breaking its war machine.

It was strongly suspected that this would eventually trigger a war with Japan, so when, on September 24, a Japanese cable was intercepted that suggested a sneak attack was being planned, the Roosevelt Administration took it very seriously. One of Roosevelt’s first acts was to commission Detroit-based businessman Curtis Munson to investigate the loyalty of America’s Japanese population.

The Munson Report, as it came to be known, was assembled in record time. Munson delivered his draft copy on October 7, and the final version was on Roosevelt’s desk a month later, on November 7. The report’s findings were unequivocal: No threat of armed insurrection or other sabotage among the overwhelmingly loyal Japanese-American population existed.

Many of them had never even been to Japan, and quite a few of the younger ones didn’t speak Japanese. Even among the older, Japan-born Isei, opinions and sentiment were strongly pro-American and were not likely to waver in the event of war with their mother country.

Taken in isolation, the Munson Report strikes a hopeful note about Americans’ ability to set aside differences of race and national origin and build healthy communities. Unfortunately, the Munson Report was not taken in isolation. By the end of November, thousands of law-abiding Japanese-Americans had secretly been designated “high-risk” and were quietly arrested. These unlucky people would have to hear about America’s Day of Infamy from inside their jail cells. Worse was yet to come.

Executing Order 9066 For Japanese-American Internment

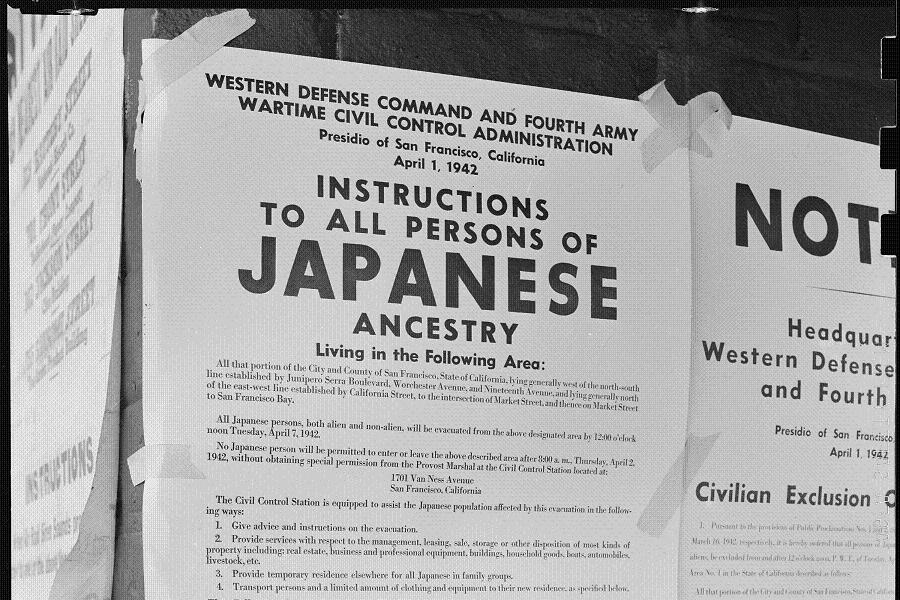

Wikimedia CommonsTens of thousands of families were informed of their outlaw status by publicly posted notices such as these, hung at the intersection of First and Front Streets in San Francisco.

Immediately after the December 7 attack on Pearl Harbor, Americans were angry and looking for a way to deal with the blow. Ambitious politicians were happy to oblige and played to the worst instincts of a frightened public. Then-Attorney General and later California Governor Earl Warren, the man who would later drive the Supreme Court to adopt groundbreaking anti-segregation rulings, wholeheartedly supported the removal of ethnic Japanese in California.

Though removal was a federal policy, Warren’s support paved the way for its smooth execution in his state. Even in 1943, when fear of Japanese Fifth Column activities had become completely untenable, Warren still supported internment enough to tell a group of fellow lawyers:

“If the Japs are released, no one will be able to tell a saboteur from any other Jap. . . We don’t want to have a second Pearl Harbor in California. We don’t propose to have the Japs back in California during this war if there is any lawful means of preventing it.”

Warren wasn’t alone in his sentiments. Assistant War Secretary John McCloy and others in the Army command prevailed on President Roosevelt to sign Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. This order, which the Supreme Court later found to be constitutional, established an “Exclusion Zone” that started on the coast and covered the western halves of Washington and Oregon, all of California to the Nevada border, and the southern half of Arizona.

The 120,000 designated “Enemy Aliens” in this zone were unceremoniously rounded up and shipped out. They were given virtually no time to sell their possessions, homes, or businesses, and most lost everything they had ever owned. Civilians who hindered the evacuations – say, by hiding Japanese friends or lying about their whereabouts – were subject to fines and imprisonment themselves. By the spring of 1942, the evacuations were underway across the Exclusion Zone.

“We Were All Innocent”

Oral History ProjectWomen and children crowd together behind barbed wire to greet new arrivals to their camp.

For Japanese-Americans caught up in the early arrests, the first sign of trouble came when the FBI and local police knocked on their doors. Katsuma Mukaeda, a young man then living in Southern California, was one of the first caught in the net. In his own words:

“On the evening of December 7, 1941, I had a meeting about a dance program. . . I went home at about 10:00 p.m. after the meeting. At about 11:00 p.m. the FBI and other policemen came to my home. They asked me to come along with them, so I followed them. They picked up one of my friends who lived over in the Silver Lake area. It took over an hour to find his home, so I arrived at the Los Angeles Police Station after 3:00 that night. I was thrown into jail there. They asked for my name and then whether I was connected with the Japanese Consulate. That was all that occurred that night.

In the morning, we were taken to Lincoln City Jail, and we were confined there. I think it was about a week, and then we were transferred to the county jail, in the Hall of Justice. We stayed there about ten days and then we were transferred to the detention camp at Missoula, Montana.”

Other Japanese-Americans got the news after Public Law 503 was enacted (with just one hour of debate in the Senate) in March 1942. This law provided for the legal removal and internment of civilians, and it sent the message to its intended victims that nobody would be spared. Marielle Tsukamoto, who was a child at the time, later recalled the atmosphere of dread:

“I think the saddest memory is the day we had to leave our farm. I know my mother and father were worried. They did not know what would happen to us. We had no idea where we would be sent. People were all crying and many families were upset. Some believed we would not be treated well, and maybe killed. There were many disturbing rumors. Everyone was easily upset and there were many arguments. It was a horrible experience for all of us, the old people like my grandparents, my parents and children like me. We were all innocent”

Early Days At The Camps

ROBYN BECK/AFP/Getty ImagesMany internment camps were intended to be self-supporting, but poor soil and unpredictable rainfall made farming virtually impossible at camps such as Manzanar, in the California Desert.

When Katsuma Mukaeda and his friend were arrested, they had to be taken to local jails because there was no other place to house them. As the number of internees increased, space became scarce and the authorities began thinking about solutions to the logistical challenges of housing over 100,000 people.

The answer, which only took a few months to put together, was to build a network of 10 concentration camps for the Japanese. These were usually situated in very remote, very harsh locations, such as California’s Manzanar camp, which sat in the baking desert of Inyo Country, or the Topaz center, where Marielle Tsukamoto’s family was sent, along with future actor Jack Soo of Barney Miller fame, which squatted on an empty desert flat in Millard County, Utah.

Camp planners had intended these facilities to be self-supporting. Many Japanese-Americans at that time worked in landscaping and agriculture, and planers expected that the camp facilities would grow enough of their own food to operate independently. This was not the case. The average camp held between 8,000 and 18,000 people and sat on almost completely unproductive land, which made attempts at large-scale agriculture futile.

Instead, adults in the camp were offered jobs – often making camouflage netting or other War Department projects – that paid $5 a day and (theoretically) generated the revenue to import food to the camps. In time, a stable economy grew inside the centers, with families earning some money and local traders plugging the gaps with black market items bought from guards. Unbelievably, life started to stabilize for the inmates.

Life In A Camp

ROBYN BECK/AFP/Getty ImagesA solitary guard tower stands on the site of California’s Manzanar facility. These towers sported sniper’s perches and a .30-cal machine gun nest

It wasn’t always a smooth transition. Though the prisoners usually arrived at their camps as families, lending an element of stability that was lacking in other countries’ concentration camps, it was inevitable that some inmates would grind against the camp authorities. The camp at Tule Lake, located on California’s remote Lassen Lava Beds, and the camp that housed George Takei‘s family from Los Angeles, was set aside for discipline cases and internees who refused to swear to obscene loyalty oaths in other camps.

It was there that Ben Takashita’s older brother started organizing other inmates to make demands on camp personnel. His activities, coming as they did from a man already suspected of subversion, would not be tolerated. Eventually, camp guards had had enough. According to Ben, one day a squad of military police came to take his brother away. They drove him out into the wilderness under guard, where according to Ben:

“They got to a point where they said, ‘Okay, we’re going to take you out.’ And it was obvious that he was going before a firing squad with MPs ready with rifles. He was asked if he wanted a cigarette; he said no. . . You want a blindfold? No. They said, ‘Stand up here,’ and they went as far as saying, ‘Ready, aim, fire,’ and pulling the trigger, but the rifles had no bullets. They just went click.”

Terror tactics like this brought many of the agitators in the camps under control, but there was definitely a line that camp guards had to observe. That line was crossed at Topaz in March 1943, when a sentry shot a 63-year-old chef named James Wakasa for walking too close to the perimeter fence. Former inmate Ted Nagata remembered the incident:

“Somebody said [Wakasa] was hard of hearing, and the guard told him to stop, and he didn’t understand.”

One month later, another guard fired a warning shot at a couple walking near the fence. These incidents horrified the inmates, who immediately went on strike, refusing to do any war work or cooperate with the authorities. Higher-ups seem to have realized their error, and from that spring they started making changes to how the camps were run.

Restrictions and Changing Control

The changes mostly involved a demilitarization and loosening of control over the camps, as if the camp management had developed a bad conscience their superiors still lacked. According to Nagata, by the end of 1943:

“[T]he security in Topaz was nonexistent. In fact, there were no more guards up there, there were no guns, and nobody was in the guard towers.”

This dropping of the guard created a bizarre disconnect between the illusion of liberty and the real confinement the inmates still had to deal with. Though armed guards were removed and children were allowed to go on field trips outside the wire – and some men in the camps were allowed to work in nearby towns – nobody was really free to go. Reiko Komoto, whose family was sent to Topaz when she was nine years old, described the odd, partly free life after the demilitarization:

“In the beginning, guards with questionable intelligence manned the towers around the fenced camp. However, even if one could escape there was no place to go in the desert, in Utah, on foot, with an Asian face. Eventually, the guards were gone but no one tried to escape. A person could legitimately leave the camp if a person relocated to any place but the West Coast.”

Held By More Than A Fence

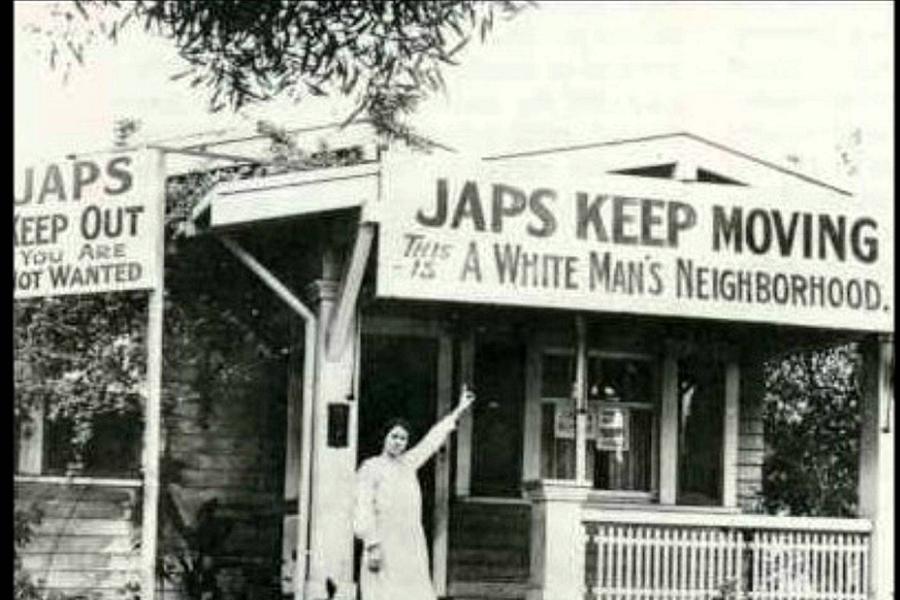

Ken Gilhooly/TwitterEven when the military discipline was loosened, internees were still trapped by the hatred of society at large. Even Dr. Seuss, then an illustrator for PM, published propaganda, such as this image depicting countless Japanese civilians collecting TNT and waiting for orders to attack.

Maybe it would have been nice to leave the camps and “relocate to any place but the West Coast,” but there was nowhere to go. Like the slaves of the Antebellum South, Japanese internees were trapped by more than a fence; there was no city or town where they could move in with family or find work.

The war was still on, and though many of the camp inmates had sons fighting for freedom in Europe, no American law protected their right to earn a living in Chicago or Detroit, even if they had had the means to move there. They were ultimately trapped by reality itself and could only wait until the government said they could go back to the towns they had left in 1942.

By the end of the war, the camps were more like dormitories than Dachau. The people inside them had nothing outside the wire, and it was necessary to house them until some kind of life could be salvaged back in the world. When it was announced that all U.S. citizens were going to be discharged straight back into society – with no money, prospects, or other support – people panicked.

Many actually renounced their citizenship just to stay in what had become their homes long enough to get their lives back on track. Courts later ruled that these renunciations were later ruled by the courts to have been made under duress, and so could be reversed at the former inmate’s request.

Release, Reparations, and Remembrance

Justin Sullivan/Getty ImagesMemorials now stand in camp locations as mute testimonies to what happened.

Those who didn’t renounce their citizenship for a brief extension of their stay were mostly hustled up in front of a loyalty board that rubber-stamped their freedom papers and sent them packing. Katsuma Mukaeda, the young man who had been arrested on Pearl Harbor Day, recalled the process:

“I spent four years and one month in internment. . . I was released from the Department of Justice after a hearing in December 1945. The release order came on February 11, 1946. In order to prepare and get the tickets for the train, I left there one week afterward. It was February 19 when I came to Los Angeles.”

Recently released inmates had nothing to fall back on. Their homes were gone, their businesses were sold for whatever they could get at the time, and they usually didn’t have much money. George Takei’s family returned to Los Angeles and went straight to Skid Row, where his father struggled to pick up the pieces of their lives. In time, between intact families and a strong sense of community and the value of work, most displaced Japanese-Americans recovered from their ordeal, even if their sense of security never returned.

In 1980, Congress opened an investigation into the military necessity and fundamental justice of internment. Three years later, the committee issued a report that acknowledged the responsibility of the government for the wrongs of the camps and recommended reparations for surviving victims.

In 1988, President Reagan signed legislation authorizing $1.2 billion in reparations, which was amended in 1992 with an additional $400 million for survivors. Perhaps more importantly, and almost certainly of more satisfaction to the former internees, in 2001 Congress took action to establish the 10 camp locations as historical landmarks and to preserve them as a warning of what frightened, angry people are capable of doing, even and especially in America.

Next, see what the Japanese-American internment camps looked like in these photos, and learn about the ways the time the U.S. intentionally exposed its own citizens to radiation.