Jocelyn Bell Burnell has been a pioneer in the astrophysics field. Her story highlights the importance of women and minority representation in the STEM field.

Colin McPherson/Corbis via Getty ImagesAcclaimed Northern Irish astrophysicist Jocelyn Bell Burnell, pictured in 2011.

More than a half-century after her groundbreaking discovery, female astrophysicist Jocelyn Bell Burnell is finally receiving recognition for her achievement.

In a recent statement, the committee for the Breakthrough Prize announced that Jocelyn Bell Burnell will be awarded their prestigious prize in Fundamental Physics for her work as a graduate student in 1967 when she discovered the astrophysics phenomenon known as pulsars.

This is only the fourth time that the Breakthrough Prize has been awarded. The prize comes not only with international recognition but also with three million dollars.

Bell Burnell has announced that she plans to donate her winnings to help under-represented groups become physics researchers.

Bell Burnell’s supervisor went on to win the Nobel Prize in 1974 for their work on the discovery. Bell Burnell was consequently snubbed.

But Jocelyn Bell Burnell has been and continues to be a pioneer in astrophysics. For over 50 years her discoveries, research, and teachings have impacted her academic community and the greater scientific world.

Jocelyn Bell Burnell’s Life And Career

Jocelyn Bell Burnell was born in Lurgan, North Ireland in 1943. According to The Guardian, she went on to pursue a Ph.D. at the University of Cambridge at the university’s Cavendish laboratory.

Since graduating, Bell Burnell has taught at multiple top research institutes like the University of Oxford and Trinity College Dublin. She’s also served as the project manager for the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii.

PA Archive/PA ImagesJocelyn Bell Burnell at 31, at her home in Horsham.

Bell Burnell has also served as the President of the Royal Astronomical Society and she was the first female President of the Institute of Physics and the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

She’s also been awarded a CBE and a DBE which is recognition from the British Empire in civil service, in 1999 and 2007 respectively, for her services to the field of astronomy. However, without a doubt, her biggest contribution to the field came when she was still a student at Cambridge.

Her Groundbreaking Discovery

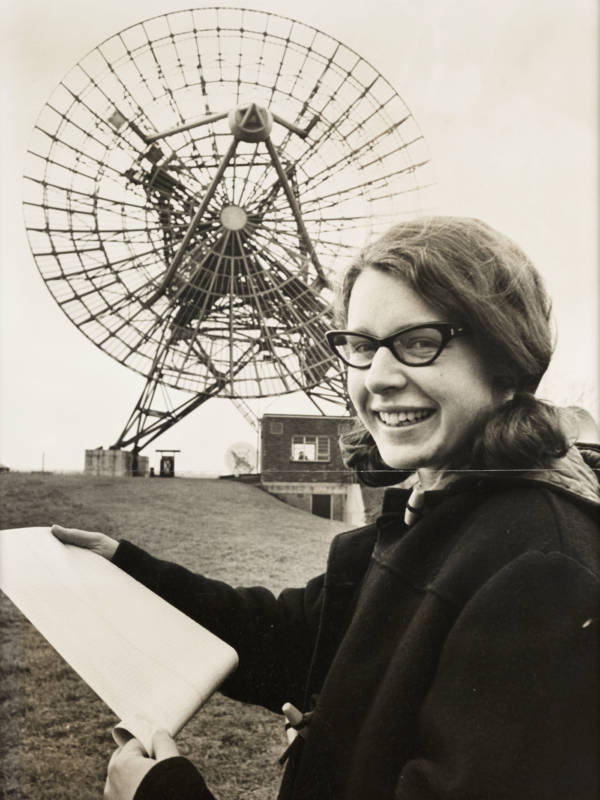

Daily Herald Archive/SSPL via Getty ImagesBell Burnell in 1968 at the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory at Cambridge University.

In 1967, while working on her dissertation for her Ph.D., Jocelyn Bell Burnell noticed something strange. She was poring over data from a new radio telescope that she and her supervisor Antony Hewish built when she found an unexpected signal.

The signal, or radio waves, in her data pulsed repeatedly and with great tenacity and brilliance. She characterized the signal and showed that it originated from space. These pulsing radio waves became known as pulsars, which were found to be rapidly spinning neutron stars. At first, Bell Burnell doubted her discovery.

“It was a very, very small signal,” she told The Guardian. “It occupied about one part in 100,000 of the three miles of chart data I had. I noticed it because I was being really careful, really thorough, because of imposter syndrome.”

Imposter syndrome comes when a person doubts their achievements, believing they aren’t good enough and that they could at any moment be discovered as a fraud. For Bell Burnell, it manifested as a fear of being thrown out of Cambridge, but she overcame her fear and revealed her findings to her supervisor.

According to NPR, her observation is considered one of the greatest astronomical discoveries of the 20th century.

Despite the pivotal role she played in the discovery, the 1974 Nobel Prize for the work went to her supervisor and Bell Burnell was largely unacknowledged.

Recent Recognition For Her Discovery

David Hartley/Rex/ShutterstockBell Burnell.

50 years after she observed pulsars for the first time, Jocelyn Bell Burnell is finally receiving the much-deserved recognition for her work.

The Breakthrough Prize is the largest monetary science prize in the entire world. Funded by Silicon Valley giants like Sergey Brin and Mark Zuckerburg, Bell Burnell joins a high-profile group of past winners like Stephen Hawking.

“Jocelyn Bell Burnell’s discovery of pulsars will always stand as one of the great surprises in the history of astronomy,” Edward Witten, the chair of the prize’s selection committee, said in a statement. “Until that moment, no one had any real idea how neutron stars could be observed if indeed they existed. Suddenly it turned out that nature has provided an incredibly precise way to observe these objects, something that has led to many later advances.”

Plans For The Prize Money

Jocelyn Bell Burnell already has big plans for her prize money. She told the BBC, that she plans to donate all of her winnings to under-represented groups in order to help them with funding to become physics researchers.

“I don’t want or need the money myself and it seemed to me that this was perhaps the best use I could put to it,” she told the BBC.

She’s putting the funds towards helping ethnic minority and refugee students in hopes that they can bring fresh perspectives and ideas to the field. Her own minority status, as a woman in the field, is something she believes helped her make her groundbreaking discovery.

“I found pulsars because I was a minority person and feeling a bit overawed at Cambridge,” she said. “I was both female but also from the north-west of the country and I think everybody else around me was southern English.”

“So I have this hunch that minority folk bring a fresh angle on things and that is often a very productive thing,” she continued. “In general, a lot of breakthroughs come from left field.”

As for any bitterness about being passed over for the Nobel Prize when she first discovered it, Bell Burnell doesn’t have any and said that she thinks she’s gotten a way better deal.

“I feel I’ve done very well out of not getting a Nobel prize,” she told The Guardian. “If you get a Nobel prize you have this fantastic week and then nobody gives you anything else. If you don’t get a Nobel prize you get everything that moves. Almost every year there’s been some sort of party because I’ve gotten another award. That’s much more fun.”

After learning about Jocelyn Bell Burnell, discover the story of Carl Von Ossietzky, a journalist who won the Nobel Prize but the Nazis wouldn’t let him accept it. After that, meet Fritz Haber, a Nobel Peace Prize winner and the father of chemical warfare.