In 1923, Dr. John Brinkley broadcast that he had found a cure-all for impotence and insanity alike in goat testicles — until it was discovered that he was, in fact, a quack.

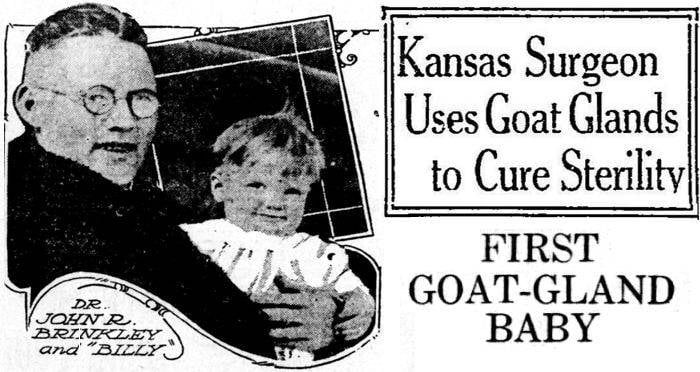

Wikimedia CommonsDr. John Brinkley and Billy, the first baby born after the goat gland graft, Feb. 20, 1920.

Dr. John Brinkley claimed to have found a cure for almost any ailment. For $750, (which by today’s standards is closer to $10,000), Dr. Brinkley’s Goat Gonad Gland Graft declared that it could increase, maintain, and strengthen masculine virility — among other miracles.

Of course, John Brinkley had his nay-sayers. Both the legitimacy of his research and his medical degree were in constant question throughout his practice and for good reason. Moreover, he was responsible for some dozen cases of malpractice.

But from 1918 to 1930, Brinkley surgically grafted goat glands onto so many men across America that, at his peak, he was said to bring in $12 million each year.

He was a celebrated radio broadcaster and healer, he owned a large estate, a yacht, and had a go for Kansas governor. Indeed, the journey of Dr. John Brinkley was certainly a colorful one. It’s just too bad John Brinkley’s career involved more finagling than it did medical training.

The Early Life Of John Brinkley

John R. Brinkley in 1922.

Illegitimacy seemed to be a theme in the life of John Romulus Brinkley. He was born the illegitimate son of his father and his mother’s niece on July 8, 1885, in Beta, N.C.

Brinkley’s father was a country physician who died in 1896 which led Brinkley to become the family’s breadwinner. He worked as a telegraph operator and delivered mail while tirelessly studying the bible and home remedies in his spare time.

After he’d spent some time as a traveling telegrapher, Brinkley married and his nomadic business changed. Together with his wife, Sally Wike, Brinkley staged a theatrical play to attract crowds to whom he could then sell tonics and herbal medicines as quack doctors.

Meanwhile, the Brinkley’s accrued some debt.

Perhaps in an effort to legitimize his cure-all tonic business, Brinkley moved his family to Chicago in order to enroll in the Bennett Medical College. But the debt crippled Brinkley and he was forced to drop out of school shy of his degree. Because he could not pay his debts, other medical colleges refused to accept him.

Determined to become a doctor, John Brinkley began to practice as a “men’s specialist” in Knoxville and Chattanooga, Tenn. Around this time he left his wife and remarried. He then procured work as an “Electro Medic Doctor” in Greenville, S.C where he would inject patients with “electric medicine from Germany,” that alleged it could strengthen masculine virility. In reality, the medicine was likely colored water.

Debt consequently found Brinkley again and this time it ended in a brief jail sentence.

He was later bailed out by his new father-in-law and moved to Judsonia, Ark. in the summer of 1914, where he opened a practice as a specialist in diseases of women and children. There, his work began to garner recognition by locals.

He managed to enroll at the Eclectic Medical University in Kansas City, perhaps through a phony diploma. It would be discovered decades later that he applied for an illegitimate certification through a diploma mill years earlier which would enable him to be accepted at the University in Kansas. Regardless, he didn’t last long at the Medical University and dropped out.

John Brinkley managed to maintain his track to becoming a doctor, however, and after settling in Milford, Kan. in 1916, established what would become his medical breakthrough.

The First Goat Gland Operation

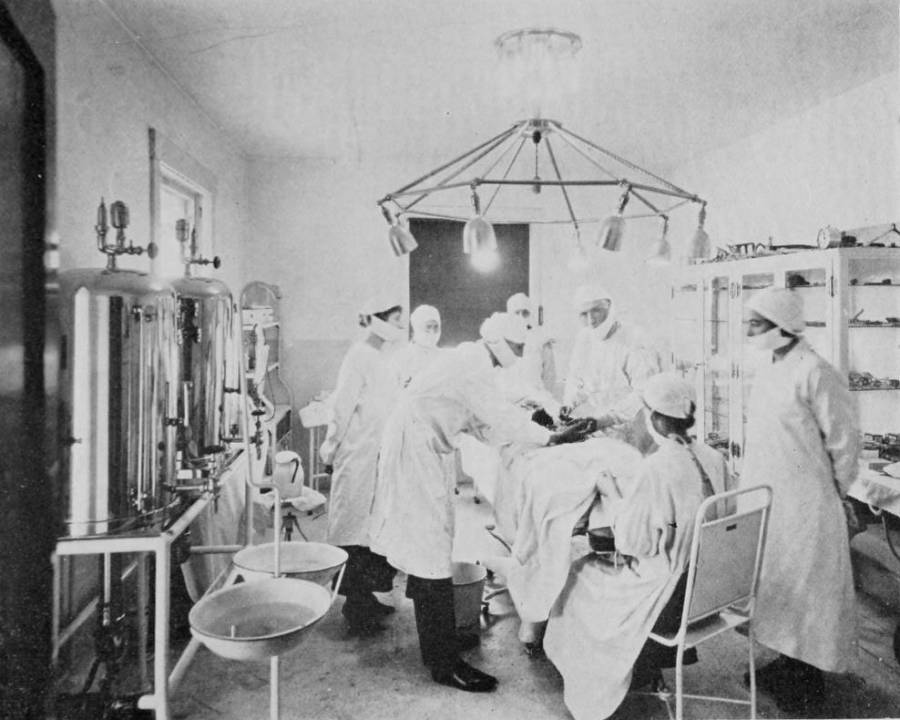

Wikimedia CommonsThe operating room at Dr. John Brinkley’s hospital in Milford, Kan., 1921.

For a couple of years in Milford, Brinkley made an honest living. He ran a 16-room clinic where he helped nurse the victims of a flu pandemic back to health, and his community respected and appreciated his efforts.

But when a patient complained that he struggled with impotence, Brinkley hit on the idea that would make him a millionaire.

The legend of the fateful visit occurred at the farm of a patient who claimed to be “sexually weak.” Brinkley, halfway joking, pointed at a goats’ testicles and said: “You wouldn’t have any trouble if you had a pair of those buck glands in you.”

“Well, why don’t you put ‘em in?” The farmer famously replied. “Why don’t you go ahead and put a pair of goat glands in me? Transplant ‘em, graft ‘em on, the way I’d graft a Pound Sweet on an apple stray.”

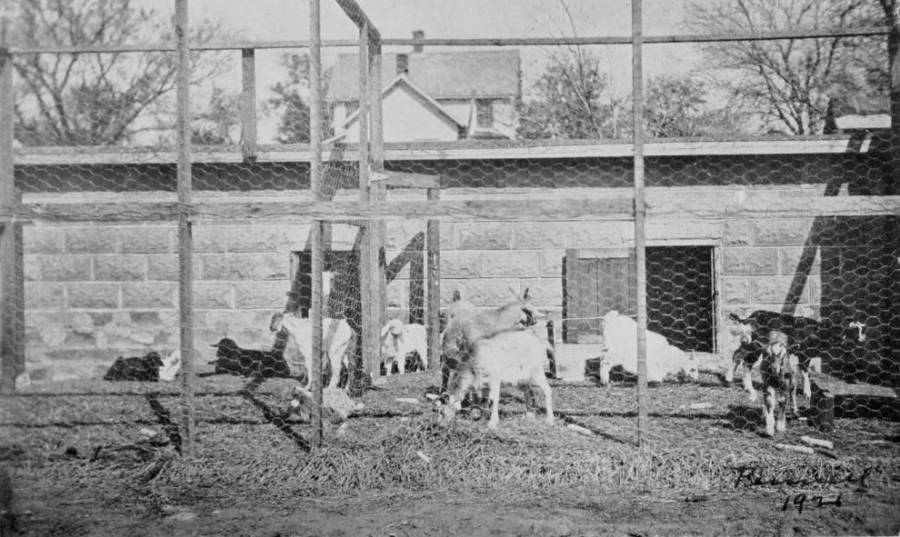

Wikimedia CommonsToggenburg goats, the breed used by Dr. John R. Brinkley for his goat-gland transplantations, 1921.

So Brinkley did just that. One year later, that farmer’s wife gave birth to a little boy named “Billy”: the first baby born of the goat-gland procedure.

Word spread, and soon, Brinkley’s clinic was filled with men willing to pay $750 to have a goat’s testicles implanted onto their scrotum.

It started as small-town fame but Brinkley became a national sensation in 1922 when, Harry Chandler, the owner of the Los Angeles Times, invited him to perform the operation on one of his editors — which Chandler believed to be a total success.

On April 22, 1922, the headlines of the Los Angeles Times read in bold letters:

“NEW LIFE IN GLANDS – DR. BRINKLEY’S PATIENTS HERE SHOW IMPROVEMENTS – MANY VICTIMS OF ‘INCURABLE’ DISEASES ARE CURED – TWELVE HUNDRED OPERATIONS ARE ALL SUCCESSFUL.”

Thus Brinkley’s goat-gland operations became world famous and after years of struggling to pay his debts, John Brinkley became a millionaire.

The Miracle Cure

Carl Mydans/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesA view of Dr. John Brinkley’s estate, 1939.

Goat glands, Brinkley soon began to claim, weren’t just an impotence cure. They could cure almost anything. Influenza and insomnia went away after every goat gland operation, he claimed, while the insane would see clearly within just 36 hours of an operation.

Brinkley’s stories were incredible. In one paper, he described the miracle recovery of a patient no insane asylum could help:

“The second day after two male goat glands had been inserted he spoke to me, saying, ‘Doctor, won’t you please remove the straps so I can rest comfortably? I am perfectly aware of everything now and feel as if snatched from the grave.'”

After all, Brinkley posited, the root of almost every problem started in the glands. He wrote: “90 percent insanity cases and 75 percent of divorce cases are due to diseased glands.”

Brinkley also marketed like no one ever had. He filled newspapers with ads of himself holding little baby Billy, the world’s first goat-gland child. He publicized operations on senators and stars alike, and in 1923, he even set up his own radio station.

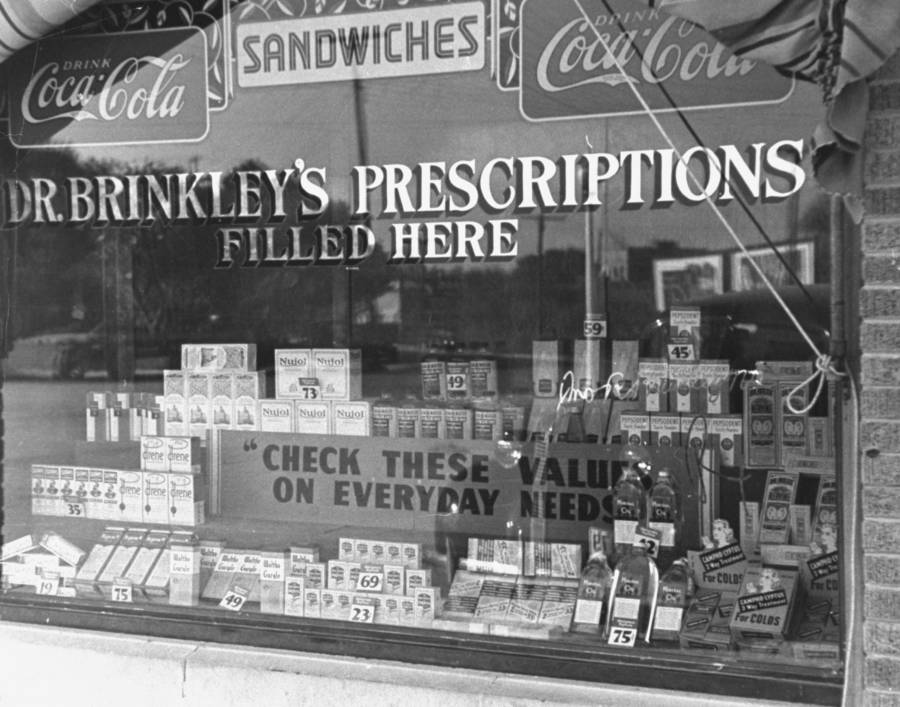

It was called KFKB: Kansas First, Kansas Best. For the most part, the station operated as a hub of advertisements for John Brinkley’s operations. One of his most popular shows was the “Medical Question Box,” where he would read listeners’ medical complaints and explain to them how they could be treated by either goat gland or one of the licensed products sold at Brinkley’s pharmacies.

A sign advertising where Dr. John R. Brinkley’s prescriptions can be filled, 1939.

Brinkley had a miracle cure; and nobody in the world, he claimed, could pull it off but him. There was such a fine art to goat gland surgery, Brinkley claimed, it “cannot be taught by correspondence, and, simple though it sounds to hear it, it cannot be

Though Brinkley claimed his work could not be replicated or “learned by attendance at a few clinics,” modern experts believe that the process was apparently fairly archaic. The surgery involved simply sewing a young goat’s testicle onto a patient’s scrotum. Brinkley did not join the testicle with blood vessels and consequently, the gland did not actually interact with the patients’ bodies internally — and had no real medical foundation.

The Demise And Death Of The Gonad Doctor

Keystone-France/Gamma-RaphoDr. John Brinkley, photographed shortly after losing his medical license, Milford, Kan., July 3, 1930.

Not everybody bought into the goat-gland bonanza. From the start, the American Medical Association knew the operation was a farce and they did everything in their power to shut John Brinkley down.

But Brinkley fought back. He would go on the radio and fill the airwaves with vicious diatribes in which he called the AMA a “meat-cutters union” who just couldn’t compete with his miracle cure. Because Brinkley held a fortune which he circulated generously throughout Kansas, the governor fought to protect him himself.

But in 1930, the Kansas Medical Board held a hearing to see if Brinkley’s license should be revoked, and they discovered something they couldn’t ignore: Brinkley had signed 42 death certificates.

Brinkley lost his medical license and, six months later, he lost his radio station, too. The Federal Radio Commission refused to renew his contract.

Dr. John Brinkley and his wife during better days, 1921.

For years, John Brinkley dabbled in other schemes. He ran for Governor of Kansas, hoping to use his power to renew his license but lost. Then he started broadcasting his radio into Mexico, where he couldn’t be censored.

But what little he had left disappeared in 1938 when Dr. Morris Fishbein wrote an article calling Brinkley a “modern medical charlatan.”

Brinkley sued him for libel, demanding $250,000, but the judge accepted that Fishbein had written nothing but the plain, honest truth. Brinkley, the judgment read, “should be considered a charlatan and quack in the ordinary, well-understood meaning of those words.”

The ruling paved the way for a barrage of lawsuits. Brinkley was sued for more than $3 million, all in all, and became completely bankrupt. He was also found guilty of mail fraud and due to complications concerning a blood clot, lost his leg.

On his deathbed with all the consequences of his deceptions rearing their heads, Brinkley declared:

“If Dr. Fishbein goes to heaven, I want to go the other way.”

Most believe he did just that when he died on May 26, 1942, penniless and exiled to San Antonio, Tex. In his obituary The New York Times eulogized him as a “quack” with a “gaudy career.”

Perhaps forebodingly — and somewhat ironically—, the obituary warned against the power of mass media, and “how mighty a force is radio for evil as well as good.”

After this look at quack doctor John Brinkley, check out Dr. Henry Cotton, whose patented technique killed 30 percent of his patients. Then, read up on Dr. Death, the surgeon who killed 31 people.