After Lady Moody became the first woman to found a settlement in the New World in 1645, she then established one of the first “grid systems” in what would later become New York City.

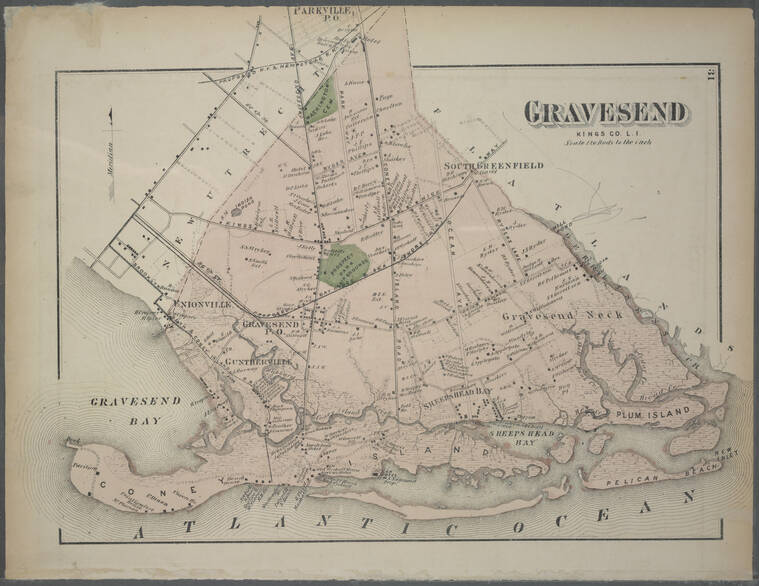

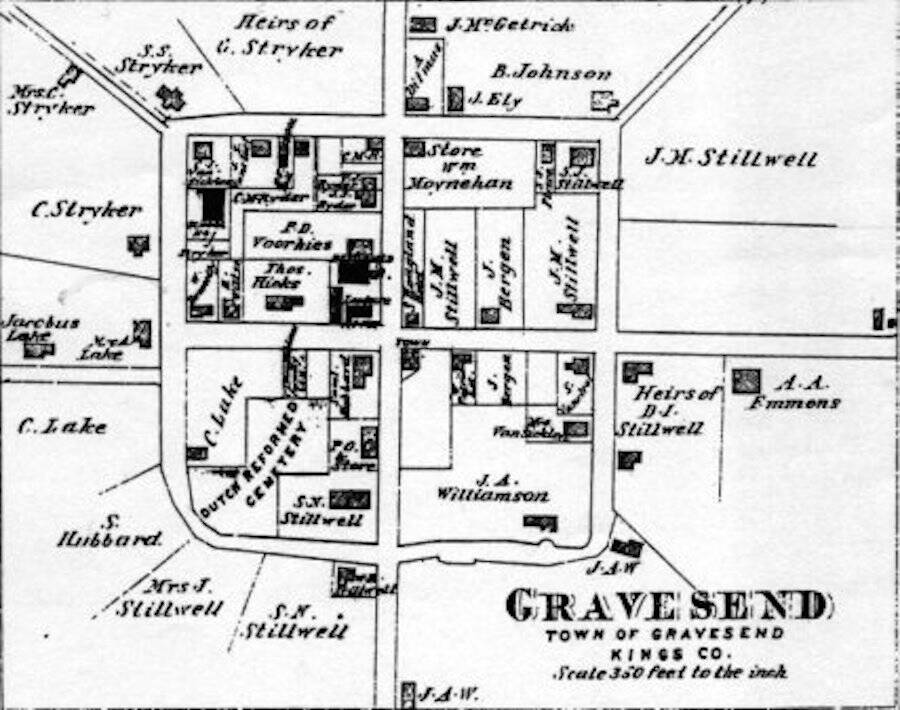

New York Public LibraryMap of Gravesend. 1873.

She was branded a “dangerous woman,” but “persisting still,” she moved to Brooklyn and founded a community based on religious freedom and rational planning. Believe it or not, the year was 1645.

This is the story of Lady Deborah Moody, the religious dissenter, landowner, and urban planner who was the first woman to found a settlement in the New World — and one of the first people to establish a “grid system” in what would later become New York City.

Lady Moody was born Deborah Dunch in England around 1583. Her family was steeped in wealth and status. Her father was a member of Parliament and her grandfather on her mother’s side was the bishop of Durham.

When her husband, Henry Moody, was knighted shortly after their marriage in 1606, Deborah became Lady Moody.

After her husband’s death in 1629, Lady Moody left her estate and moved to London, where she found comfort amongst the then-radical Anabaptists.

Why Lady Deborah Moody Left England

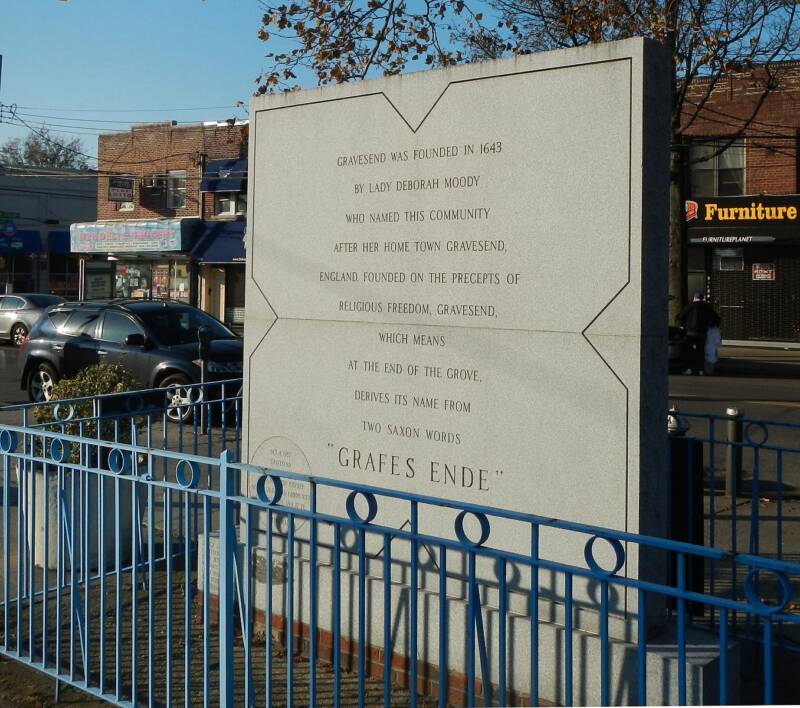

Wikimedia CommonsA monument to Lady Deborah Moody.

Anabaptists were part of a sect of Christianity that rejected infant baptism in favor of adult baptism, arguing that that people should be baptized when they could consciously choose their faith.

Such beliefs were controversial in 1630s England. At one point, Moody was even summoned to appear in court. Due to religious persecution, she decided to gather her wealth and set sail for the New World in 1639.

She understood New England to be the domain of other religious dissenters, so she sailed to Massachusetts, where her friend John Winthrop was governor.

The fact that Moody undertook this journey to a land completely unknown to her as a widow in her mid-50s speaks volumes about her character.

She believed she would be welcomed in the Salem Church. And for a time, she was. John Winthrop described her as “a wise and anciently religious woman.” But Rev. Hugh Peter cast a cold eye on her views.

Peter had been personally responsible for the excommunication of another Anabaptist named Anne Hutchinson just two years prior. Now, he turned his attention to Moody and her radical beliefs. By 1643, she was brought to court for spreading religious dissent.

Puritan leader John Endecott called her a “dangerous woman.”

Even her friend Winthrop lamented that she was “taken with the error of denying baptism to infants, was dealt withal by many of the elders and others, and admonished by the church of Salem (whereof she was a member); but persisting still, and to avoid further trouble, etc., she removed to the Dutch, at the advice of all her friends.”

Lady Moody Moves Again

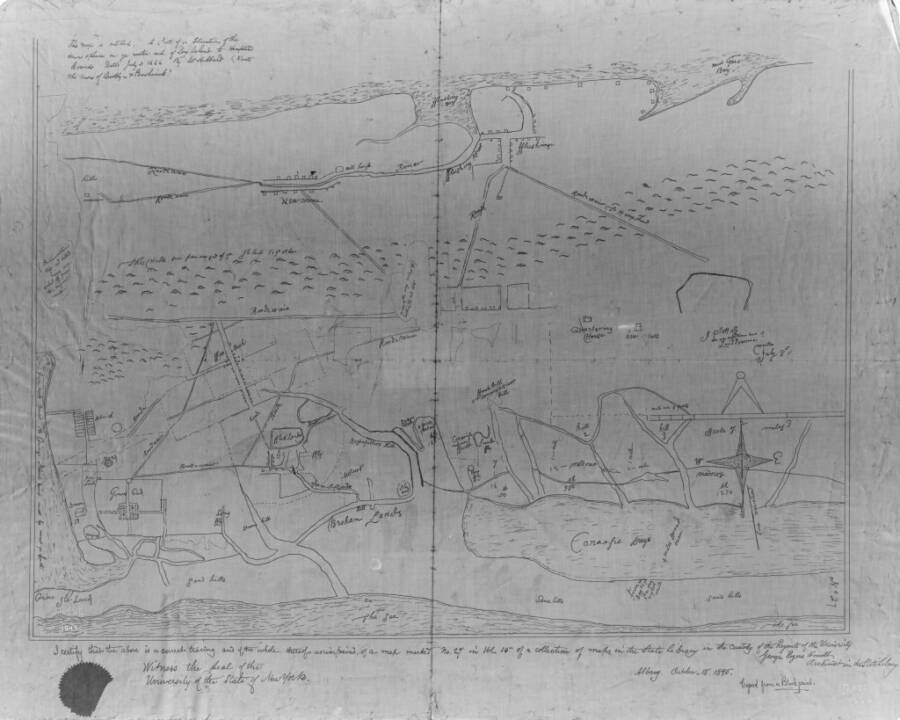

New York Historical SocietyMap of Long Island. 1666.

Rather than renounce her views, Moody once again struck out for a new world. She relocated to New Netherland in 1643, leading a group of fellow Anabaptists to what is now part of Brooklyn.

Compared to Puritan New England, New Netherland was more tolerant of religious differences. There, the governor granted Moody 7,000 acres on the southwestern tip of Long Island in 1645. She named it Gravesend.

Today’s neighborhood of Gravesend falls within this acreage, but it does not fill out the original bounds of Moody’s territory, which stretched to parts of what is now modern-day Bensonhurst, Coney Island, Brighton Beach, and Sheepshead Bay.

Moody began to develop her settlement in earnest.

That settlement was unlike any other that had been made in the New World so far. The charter, granted “unto the Honoured Lady Deborah Moody: Sir Henery Moody Barronett, Ensigne George Baxter: & Serieant James Hubbar,” was the first to list a woman first among its recipients.

It was also the first to establish an English town within a Dutch colony (it was even written in English, when the charters for the other settlements in the area were written in Dutch).

Further, it was the first document in New Netherland to grant self-rule to an individual settlement. Finally, it granted freedom of religion within the settlement, prohibiting interference from either ministers or magistrates.

Lady Moody’s Gravesend

Robert Blacklow/ New York Historical SocietyThe Van Sicklen House, on 27 Gravesend Neck Road, was long thought to be Moody’s. It stands on her farmland, but it was actually built after her death.

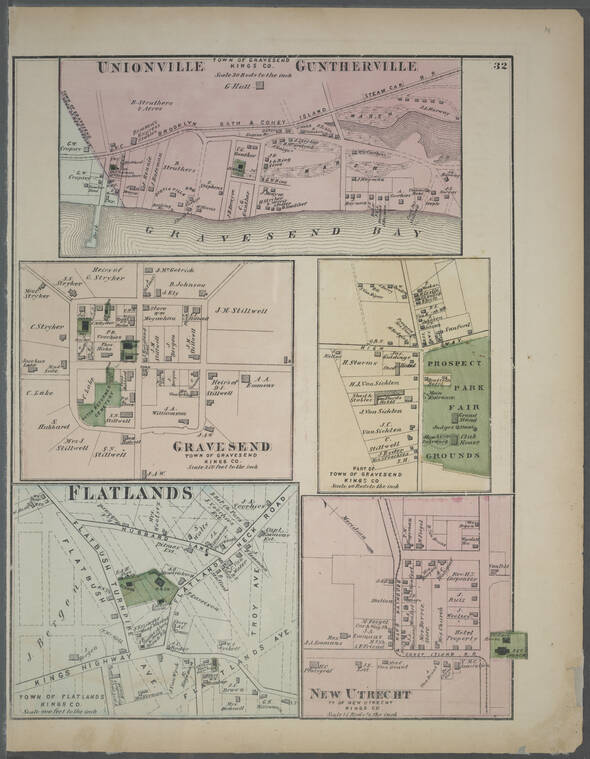

Moody made sure that Gravesend, already religiously pluralistic, would also be fairly distributed among residents. As one of the nation’s earliest city planners, she preceded New York’s 1811 grid by more than 150 years — and divided Gravesend into four quadrants.

Each quadrant was subdivided into 10 house plots. The houses bordered the streets on the perimeter of each quadrant, and the centers featured common yards for animals. Each plot holder also received a triangular piece of farmland. Unlike other settlements, Gravesend distributed plots with remarkably similar shapes and features to its settlers.

New York Public LibrarySettlements in Kings County. 1873.

Life in Gravesend celebrated a commitment to fairness, and it was contingent on each resident’s personal investment in the settlement. For example, any landholder who did not build a suitable house on their land would forfeit the land to the town.

The preeminence of town welfare was also central to the lives of early Gravesend residents. Each landholder had to pay one gilder to the common charges of the town. To protect Gravesend against wolves, townspeople were rewarded with three gilders if they shot one.

Before long, they voted together to elect a constable in 1648.

Gravesend flourished, and so did Moody’s reputation. In 1647, she was among the delegation that welcomed the colony’s new director general, Peter Stuyvesant. In 1654, Stuyvesant turned to her to mediate a tax dispute, and in 1655, he left the nomination of magistrates in Gravesend up to her.

Wikimedia CommonsMap of Gravesend. 1873.

Moody lived in Gravesend until her death in 1659. The grid she established is still in use today, and is traceable within Brooklyn’s street grid.

The ethos she championed speaks to the best elements of the American experiment, and demonstrates the way “dangerous women” have shaped this nation since its earliest days.

Now that you’ve learned about the incomparable Lady Moody, check out some of history’s most powerful speeches given by women, and 50 photos celebrating women’s history.