Legionnaire's Disease seems to be making a comeback in New York City. But what exactly is it?

TEM image of L. pneumophila, responsible for over 90% of Legionnaires’ Disease cases.

Almost 40 years to the day that a mysterious illness broke out at an American Legion conference in Philadelphia — and changed the CDC forever — the culprit appears to be making a comeback in New York City. Legionnaires’ Disease seems to have returned, but just what exactly is it?

In 1976, Philadelphia was the place to be if you wanted to think long and hard about America’s history and be aggressively patriotic. The year marked the nation’s bicentennial, and states held parades, celebrations and some of the most intense Independence Day barbecues that the US had ever seen.

July 4th, 1976 was a day for extreme patriotism. A few weeks later, Philly was still abuzz with red, white and blue — and the American Legion (an association of over two million veterans) held its annual conference at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, where 2,000 ‘legionnaires’ (as they’re called) celebrated the 200th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

The convention ran from July 21st to July 24th. The first legionnaire death occurred on July 27th.

The Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, where Legionnaires’ Disease was “born.” Source: Pennsylvania State University

Patient Zero

Ray Brennan was the Legion’s bookkeeper and an Air Force vet. At 61, the whirlwind of the three-day convention had worn him out and when he returned home on the evening of the 24th, he noted to his family that he was feeling run down. So, when he died on the 27th of an apparent heart attack, his earlier noted fatigue was seen as merely prodromal to whatever major cardiac event had been brewing.

As his family mourned, another legionnaire, Frank Aveni, also died of a supposed heart attack. By the first of August, six more legionnaires who had attended the convention in Philly were dead of apparent cardiac events.

Dr. Ernest Campbell, a physician in Bloomberg, PA, treated a few of the first legionnaires to die. He quickly realized that they had all recently attended the conference, and he immediately notified the Department of Public Health.

Within the first week after the conference, 130 of the attendees ended up in the hospital; and 25 were dead.

Attendees of the 1976 convention. Within months, two of the men pictured were dead. Source: New York Times

1976 had been a busy year for the Center for Disease Control (CDC). At the beginning of the decade they had changed their name from The Communicable Disease Center to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, seen the last reported case of smallpox and, although they didn’t yet know it, had identified the culprit behind the legionnaires’ deaths.

As summer turned to fall, the epidemiologists charged with figuring out what was making the legionnaires sick were themselves the victims of a different kind of outbreak: mass hysteria. The public, once they got wind of the cluster of legionnaire deaths, almost immediately presumed it to be swine flu.

The nation had reason to assume this: in February of that year, there had already been an outbreak at Fort Dix. Immunizations for the public showed up within the first month after the outbreak, but when three elderly patients died after receiving it, the public grew suspicious — even though there was absolutely no proof that the vaccines had lead to the patient’s deaths.

Source: Leukos

The mass panic had shifted from the flu itself to the efficacy of the vaccinations — and so, in the autumn of 1976, when the legionnaires became sick and many died, the largely unvaccinated public began to wonder if the outbreak had merely laid dormant throughout the summer and was now returning with a vengeance.

The investigation wore on for months, well into the winter of 1976 and early 1977. The CDC laboratory scientists and field epidemiologists were at a major disadvantage when it came to real-time communication: they simply didn’t have the technology.

Today, ongoing outbreak investigations have the luxury of being aided by the internet, cell-phones and video-conferencing. Field scientists are never out of communication with the lab, and they can adjust their interviews and research with patients according to what is being discovered by those looking at samples under a microscope. In 1976, however, this wasn’t yet the case, so the long slog of the investigation continued into the following year.

The scientists had, almost a year earlier, investigated an outbreak of a respiratory virus in Pontiac, Michigan, which they found was similar to the illness reported by the legionnaires and their families. While Pontiac Fever had been, at worst, a mild and self-limiting respiratory virus, whatever was killing the legionnaires was far more insidious: the men suffered severe respiratory symptoms, almost immediately developed pneumonia and had fevers that ran as high as 107 degrees Fahrenheit (41.6 degrees Celsius).

With little else to go on, and more deaths being reported, the public and the media grew increasingly unnerved by “Legionnaires’ Disease” and began prepping for an epidemic. Michael Crichton’s The Andromeda Strain had hit theaters at the beginning of the decade and so, perhaps, the American public was a little heightened to the possibility. Maybe it seemed a little bit too dramatic that, just weeks after the Bicentennial, dozens of America’s veterans had suddenly dropped dead from some mysterious illness that they had contracted while celebrating in the birthplace of the nation.

The public worried about living through their own Andromeda Strain. Source: Giphy

Even without the heat from the public, the CDC had enough reason to be concerned that perhaps they could have their own Andromeda Strain on their hands. They were having a hard time assessing the health and wellbeing of the other convention attendees and their families, and they began to fear that the infectious agent had spread out of the hotel (which had closed down) and into the streets of Philadelphia. The CDC responded by launching the largest infectious disease investigation in the agency’s history.

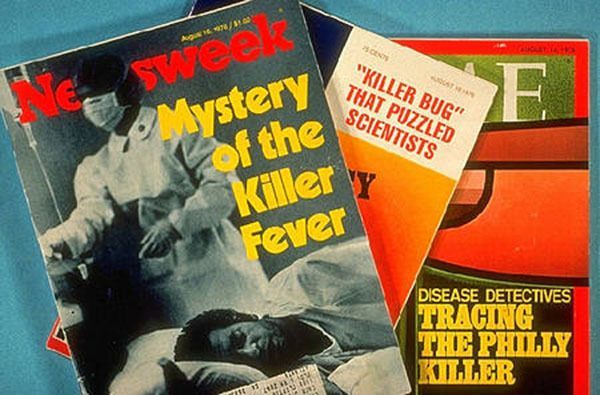

The investigation held the media’s attention for months and between the public’s fear-mongering and the work of several fearless journalists, the media probed the federal government to be accountable for the truth — was the public in danger? What had killed the veterans, and what were they doing to try to solve the mystery?

As the investigation continued, the media documented the scientists in an unprecedented manner, bringing medical technology into the homes of the American public. Investigators reviewed medical records, interviewed survivors and their families, and tracked down as many of the attendees as they could.

Bellevue-Stratford Hotel closed down temporarily so that it could be thoroughly investigated. One patient interviewed, a man named Thomas Payne, was hospitalized with a fever that spiked to 107 degrees Fahrenheit (41.6 Celsius). His account of the onset of the illness helped epidemiologists further narrow down the possible cause. He also gave them leads on other possible patients who could potentially be of help.

The first lab results definitively assured the public that no influenza of any kind was the cause of the outbreak. Officials also ruled out heavy metal poisoning and other toxins with preliminary tests that had been run months before. Pretty soon the CDC just shrugged their collective shoulders and figured the world would probably never know what caused Legionnaires’ Disease.

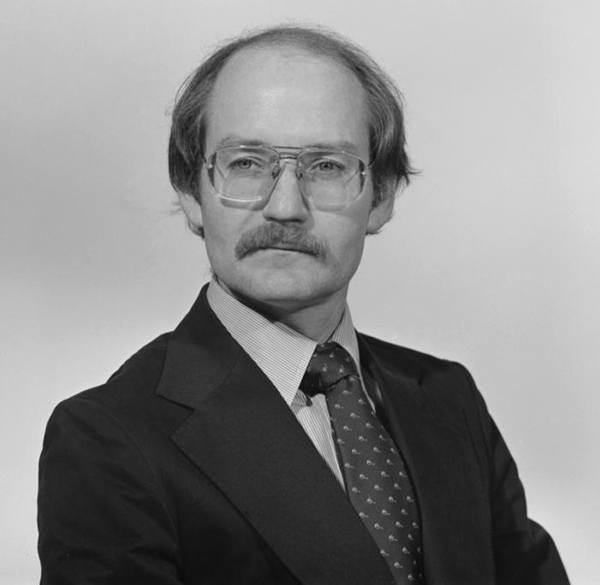

Joseph McDade. Source: Centers For Disease Control

Then, one epidemiologist, a man named Joseph McDade, got really pissed off at the company Christmas party when he was directly criticized for not solving the outbreak. He put down his drink and went back to the lab.

It took him another month, but in January of 1977 McDade successfully isolated the bacterium responsible for the outbreak, and he named it Legionella pneumophila. In fact, the bacterium had been identified before — several times–but science had largely held the belief that it only affected animals, so it had not been looked at before in the CDC’s investigations as a viable cause of the outbreak.

In fact, the same bacterium caused the fevers in Pontiac, Michigan — but it resulted in a far milder strain of the disease. Both begin with flu-like symptoms and appear similar to a run-of-the-mill respiratory virus, but Legionnaires’ routinely led to pneumonia and high fevers that quickly progressed to fatal bradycardia (slow heart rate).

Subsequent research concluded that the bacterium had been in the vents of the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel and had, therefore, been pumped through those air vents and then inhaled by attendees. Continued research would also find that the bacterium thrived in hot tubs, humidifiers and nebulizers. The prognosis was actually quite good: it could be treated successfully with specific antibiotics; antibiotics that weren’t the first line of defense by the hospitals that treated the first cases in summer of ’76.

Once the pathogen had been identified and the mystery put to rest, the CDC was suddenly forced to question some of its investigative practices. Likewise, the public no longer felt confident blindly putting their faith in the federal government to protect them from outbreaks — and both of these facts led to a reform in epidemiological standards that properly braced America for subsequent outbreaks — anthrax, HIV/AIDS and H1N1.

The CDC also developed, out of necessity, a somewhat improved relationship with the public and the media, and a bond whose legacy we see in our newspaper headlines and news tickers today.

Legionnaires’ Disease has, since 1976, had at least three more major outbreaks worldwide. Unlike some outbreaks, Legionnaires’ tends to stay in small clusters, so it has been able to be contained as soon as it is identified. The CDC has reported that as many as 18,000 hospitalizations in the US annually are a result of Legionnaires’ Disease, but that many cases are likely to go unreported- largely because the symptoms are extremely similar to influenza and pneumonia.

In the end, 221 veterans were sickened in the 1976 outbreak and 34 ultimately died.