Under the Nazi occupation of France, the Jewish-owned Parisian furniture store Lévitan was converted into a work camp where some 800 Jewish prisoners were held.

German Federal ArchivesIn their quest for total elimination of Jews, the Nazis carried out a mass pillaging operation to seize every item that once belonged to a Jewish person.

After the Nazi invasion forced Jewish people across Europe out of their homes, a systematic operation called Möbel Aktion or “Furniture Operation” set about looting thousands of personal possessions from their abandoned houses and apartments.

The seizure of these everyday items such as linens, photo frames, and even saucepans may appear banal on the surface. But it was all part of a deliberate Nazi plan to completely eliminate the Jewish population.

They gutted Jewish homes and stole every last household item in an attempt to make it appear as if the Jewish owners of these objects never existed in the first place. And they didn’t just steal these objects — they also forced Jewish prisoners to sell them.

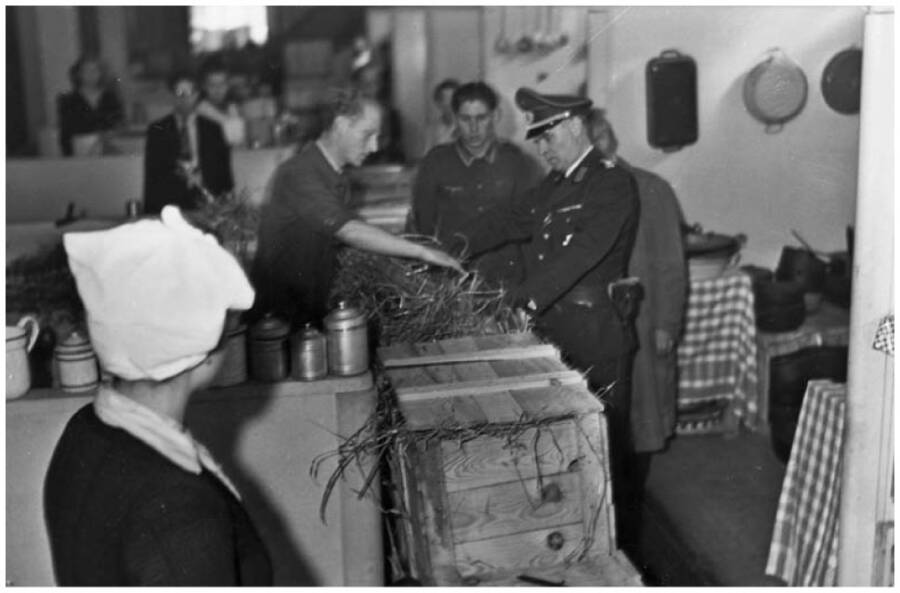

Nazi officers could browse these stolen goods for themselves at the four-story Parisian department store Lévitan. The famous storefront not only served as an “exhibit” for these plunders, but it was also a Nazi labor camp housing hundreds of Jewish prisoners.

‘Furniture Operation’ Of The Nazis

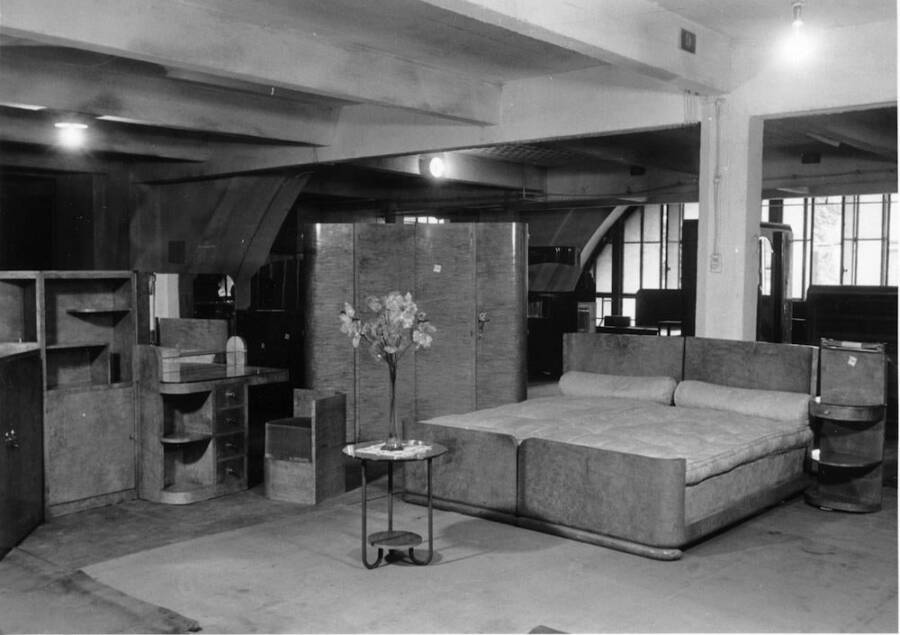

German Federal ArchivesA staged furniture setup made of household furnishings looted from Jewish families.

A key component to the capture, torture, and mass killing of the Jewish population by the Nazis during the Second World War was the seizure of artwork and valuables.

The looting was carried out under the name Möbel Aktion or ‘Furniture Operation’ and it was exactly what it sounds like: a methodical and widespread operation to take all items found in the emptied dwellings of Jewish residents, who were either kidnapped to labor camps or had fled for their lives.

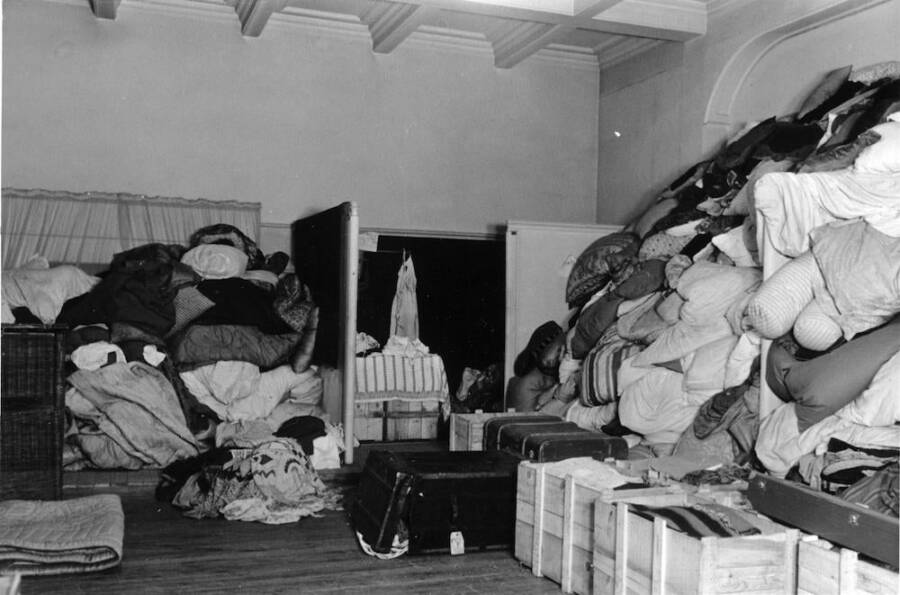

German Federal ArchivesGoods that were considered of higher value like fine linens and porcelain were kept for the Nazi officers in charge of the looting operations.

More than 70,000 dwellings across Europe were abandoned with belongings still inside ripe for looting. In France alone, 76,000 Jewish people were deported and less than a third of them ever made it back after the war. Roughly 38,000 Parisian apartments were emptied out by the Nazis.

They stripped every residence formerly occupied by Jews and transported the stolen goods, ranging from dishware and tools to cabinets and clocks. A number of warehouses were converted into work camps where hundreds of prisoners were forced to go through the mass of plundered goods. Some prisoners in these camps even came across their own stolen items.

German Federal ArchivesUnlike some of the pricey art stolen by the Nazis, these household goods remain lost to time. Some may even be sitting in plain sight in houses across Europe.

The stolen goods were divided into two categories: personal belongings and damaged items, which were set on fire at a daily bonfire on Quai de la Gare by the Germans, and things deemed fit to sell, which were sorted into categories and distributed across Nazi territories.

Lévitan, a famous four-story Parisian department store that once sold furniture, was taken over during the Nazi occupation of Paris. The storefront was converted into a labor camp where nearly 800 Jewish prisoners were detained and forced to organize and repair plundered goods under the Möbel Aktion.

Plundered Possessions At Lévitan

German Federal ArchivesRoughly 800 Jewish men and women were forced to work at the Lévitan labor camp.

Before it was occupied by Nazis, Lévitan had been a giant furniture shop owned by a Jewish entrepreneur named Wolf Lévitan.

The shop became a hub for processing and showcasing stolen goods during the war. Officers browsed and picked out looted items to send home to their families as if they were shopping for manufactured goods at IKEA.

The “staff” at Lévitan were Jewish prisoners transferred from the Drancy internment camp just outside Paris, and many of them were later sent to Auschwitz.

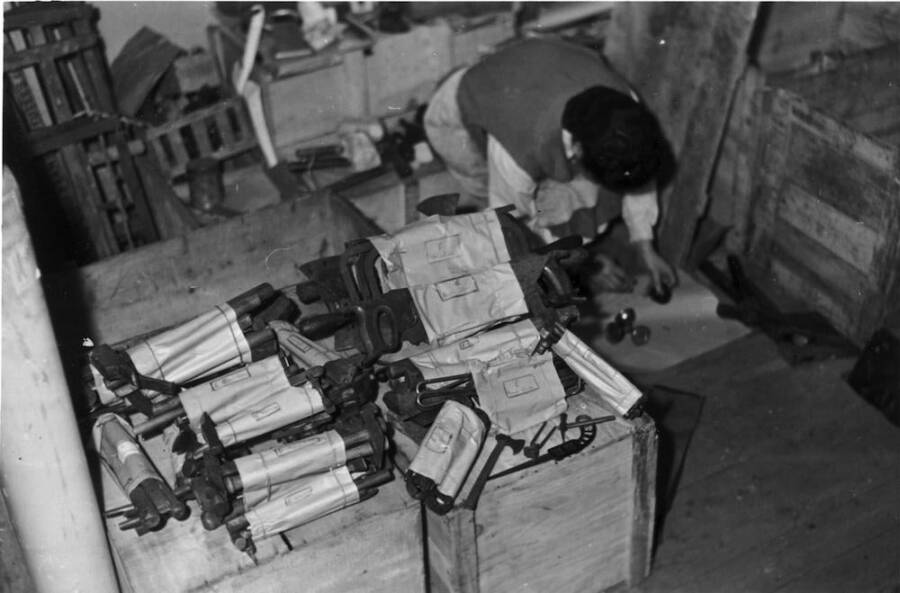

German Federal ArchivesA Jewish prisoner assembles packets of goods at Lévitan.

The first three stories of the Lévitan building were used as showrooms for the Nazi’s stolen goods while the top floor was the prison where Jewish laborers ate and slept. Jewish prisoners at the Lévitan labor camp who had vocational skills in sewing or handiwork were tasked with repairing items that were slightly damaged.

The items “sold” at Lévitan were of little value; cheap items that could easily be purchased at any regular store, unlike the priceless artworks that were also famously plundered by the Nazis across Europe. But the banality of Möbel Aktion was very much the point.

German Federal ArchivesThe stolen goods were stripped of their Jewish owners’ identities, rendering them meaningless as a way to eliminate even the memory of the Jewish population.

As noted by sociologist and author of Witnessing the Robbing of the Jews: A Photographic Album, Paris, 1940-1944 Sarah Gensburger, some of Hitler’s closest confidantes including Hermann Göring questioned the operation due to the cost of seizing and transporting millions of common objects. But it carried on anyway.

“If the project endured nonetheless,” Gensburger posits, “it’s because one of its fundamental objectives was to destroy all trace of the Jews’ very existence.”

German Federal ArchivesJewish prisoners with sewing and handiwork skills were tasked to repair items that were slightly damaged.

Not much about the Furniture Operation was left after the war, except an album of 85 photographs documenting the stolen goods that were “resold” at the Lévitan labor camp store.

The album was recovered by a member of the special task force called the Monuments Men, who were tasked to recover art pieces looted by the Nazis. The album of rare photographs is now kept in the German Federal Archives in Koblenz, Germany.

Although the objects sold at Lévitan may not have been as valuable as the priceless artworks that were also stolen by the Nazis, they nevertheless depict the magnitude of the lives that were stolen under Hitler’s regime.

Today, the former labor camp storefront still stands on Rue Faubourg Saint Martin. A small plaque on the building — now the office of an advertising agency — is the only trace of the atrocities that took place inside.

Now that you’ve read about the Nazis’ department store of stolen goods, learn about the tragic life of Czeslawa Kwoka, who died at the hands of the Nazis, though her powerful portrait at Auschwitz lives on. Then, check out the 75-year-old diary of an SS officer that could lead to 28 tons of stolen Nazi gold.