The Lowline Lab, a prototype for the larger Lowline underground park, is now open to the public in New York City.

A flower growing underground at the Lowline Lab in Manhattan. Image Source: Nickolaus Hines

James Ramsey and Dan Barasch were sharing drinks in 2009 when they decided to seriously consider an idea that sounded straight out of a 1950s science fiction movie.

Ramsey, owner of the Raad Studio design firm in Manhattan, had recently been exposed to what lay under the Lower East Side’s bustling Delancey Street: an abandoned trolley terminal. The seed of an idea to grow plants inside the empty terminal using solar technology was already growing. Barasch, vice president of the social innovation network PopTech, was looking into installing underground art in the New York City subway system. Two years later, they released an outline of an underground green space concept to the public in the form of a New York Magazine feature.

The idea of converting unused space into parks in New York City isn’t new. Even the idea of converting unused former transit space into parks in New York City isn’t new. What is new, however, is the idea of creating a living, growing underground park fed entirely by sunlight piped in from above, and a preview can now be seen in a deserted warehouse on Essex Street.

The Lowline Lab, a converted warehouse on Essex Street in Manhattan. Image Source: Nickolaus Hines

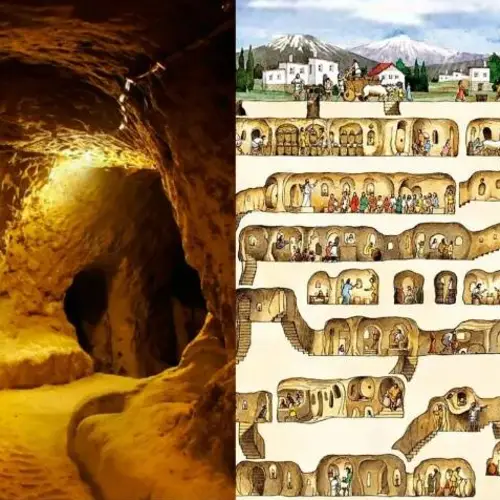

The finished concept is to build the park in the former Williamsburg Bridge Trolley Terminal in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Trolley passengers used the terminal from 1908 to 1948, but it was abandoned after the trolley service was discontinued. All that remained in the underground acre was original cobblestones, rail tracks and high vaulted ceilings.

“Instead of a mere tourist attraction, as a self-initiated project, the Lowline is actively engaging with a growing community of the Lower East Side,” Ramsey wrote in an email. “With shared ideas and imagination, our goal is to reclaim unused space for public good and give this hidden historic site located in one of the least green areas of New York City back to the community.”

With the space figured out, all that is missing is the sunlight and the plants.

What can be best described as light plumbing was needed to bring the sunlight underground. Sun Portal, a Korean company, invented a light collector that filters out infrared light and harmful ultraviolet light that would overheat the collectors in direct sunlight, yet allows essential ultraviolet rays that plants need to survive through. Ramsey completed the task by inventing a way for the light to be funneled below the surface in a type of “light plumbing.”

Rays of sunlight 30 times brighter than ambient sunlight beam from the collectors and Ramsey’s light transport system. Plant life would fry under such a concentrated beam, but a layer of lenses and reflectors measure out the levels actually reaching the plants below. In addition to doling out the light where it’s needed, a canopy of anodized aluminum panels keep the intricate piping from distracting visitors.

The ceiling of the Lowline Lab.

In short, the path of light will be as follows: A solar dish uses a helio tube to adjust to the path of the sun depending on the time of year. The sunlight is then funneled underground and hits a dome, which distributes the sunlight to the plants. Each plant is categorized as a low light plant with a high probability of survival, a medium light plant that is expected to survive or a high light plant that is experimental.

The sorting of the plants and other experimental aspects being tested is on the shoulders of the Lowline Lab. The lab is located directly above the old trolley terminal in what used to be a giant marketplace.

At 1,200 square feet, the lab is only about 5 percent of the projected size for the finished Lowline project. It is plenty of room, however, to get a feel for what it would be like to walk in an underground garden in the dead of a New York City winter.

The entrance to the Lowline Lab. Image Source: Nickolaus Hines

The only sign to the outside world of the life growing within is spray paint on a metal door. Visitors are welcome however. The free exhibit starts with large panels detailing the rich history of the area and the technology behind the transfer of solar energy. Finally, pushing through a thin black curtain, a working prototype can be explored.

There are more than 60 different plant species represented, including edible vegetation like pineapples, mint, thyme and strawberries. Edible mushrooms are on the way as well. Ramsey told us that he has though about the possibility of growing crops using this technology, which could be useful to communities that need fresh produce yet are faced with extreme weather conditions.

Pineapple being grown in the Lowline Lab. Image Source: Nickolaus Hines

The Lowline Lab was constructed in 2012 as a full-scale model to test the technology and experiment with plant species. Schools and youth programs have filled the lab since, and from October to March 2016, the lab is a free space for the community to see the experiments throughout winter.

As for the final project, more planning needs to be done. Contract negotiations with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and New York City, who own the Williamsburg Bridge Trolley Terminal, are expected to be signed by 2017 at the latest. A completed Lowline underground park is hoped to be completed and open to the public by 2020.

Until then, curious visitors hungry for growing plant life and a reprieve from the snow and the cold can visit the Lowline Lab.