Robert Nelson: The Mad Scientist Who Helped Pioneer Cryonics

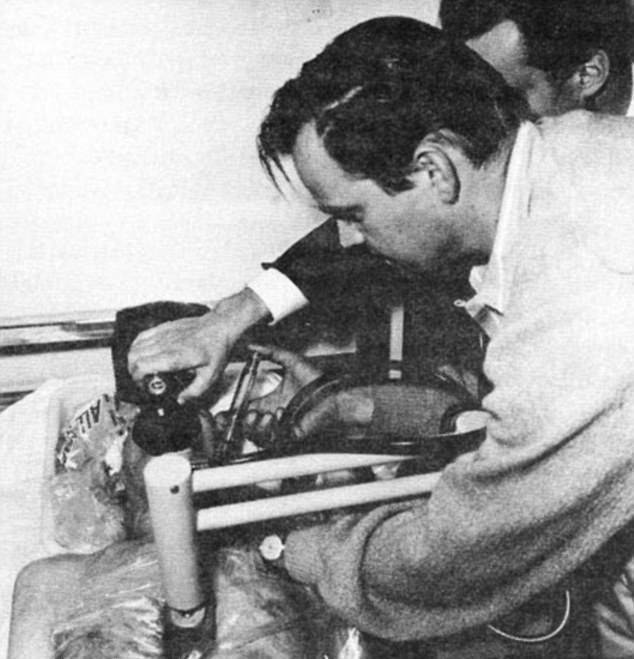

J. R. Eyerman/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesRobert Nelson (left) and biophysicist Dr. Dante Brunol cryonically freezing a participant in 1967.

Robert Nelson had no professional background or even a college degree, but nonetheless pursued his passion — cryonically freezing human beings after their death in the hopes of reviving them in the future. Born in Boston in 1936, Nelson would later plan and execute his own “cryonics” program.

Despite being a high school dropout, Nelson practically spearheaded the nascent movement by freezing his first subject in 1967. It had been a truly baffling feat for the former television repairman, who had been inspired by Dr. Robert Ettinger’s 1962 book The Prospect of Immortality.

Ettinger posited that death was merely a disease, and thus had a cure. Nelson decided to test that theory out for himself when he became president of the Cryonics Society of California in 1962 and then became president of his local Life Extension Society in Los Angeles in 1966. And before long, Nelson soon found his first volunteer.

Alcor Life Extension FoundationNelson preparing a dead Dr. James Bedford for cryonic life extension.

Dr. James Bedford was 73 years old and wanted to try extending his life via cryonics. Dying of kidney cancer, he agreed to let Nelson and his team put him on ice after he died. But the ramshackle crew was so unprepared that they initially used ice that was collected from local freezers.

Nelson then drove Bedford’s dead body from his house to the home of a friend before injecting him with antifreeze and pumping oxygen into his system with a machine called an iron heart. Then, he entombed him in a capsule filled with dry ice. In 1970, Nelson finally bought a vault to store Bedford and other volunteers who wanted to be cryonically frozen.

Underground in the Oakwood Memorial Park Cemetery in Chatsworth outside Los Angeles, the location became Bedford’s new resting place and soon held the body of the group’s first female subject, Marie Phelps-Sweet, and an eight-year-old girl who had died of cancer. Ultimately, a lack of resources and actual expertise saw the project shuttered in 1979.

The vault itself was eventually covered up with turf — with relatives of the deceased suing Nelson and his partner for $800,000. He later settled.

As for the frozen Bedford, his body was moved several times before being rehoused by the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in 1991. When he was first removed from Nelson’s care, he was reportedly found to be a “well-developed, well-nourished male who appears younger than his 73 years.”

The Alcor facility in California currently holds 184 frozen corpses, or “patients,” as they like to call them.

Years later, Nelson reflected on his experience as a former mad scientist: “It was crazy. I look back at it now, and I think, ‘Oh my God.'”

After learning about seven real-life mad scientists, take a look at history’s creepiest pictures. Then, learn about the seven craziest dictators in history.