Growing up in the White House, Tad Lincoln was a "notorious hellion," a wide-eyed observer of the catastrophe of the Civil War, and the apple of his father's eye.

Library of CongressTad Lincoln was Abraham Lincoln’s youngest son.

In the fall of 1860, seven-year-old Tad Lincoln learned that his father had been elected president. He would, alongside his parents and older brother, soon move from Springfield, Illinois to the White House in Washington D.C.

There, Tad would make his mark. As his father poured over war strategies and urged Union generals to fight harder, Tad and his brother Willie tore through the Executive Mansion. They annoyed Cabinet secretaries, delighted White House guests, and brought joy to the dreary Civil War years.

But Tad Lincoln’s four years in the White House were touched by tragedy, too. By the time Tad left the White House in 1865, he’d lost his brother to illness and his father to one of the most infamous acts in American history.

The Early Life Of Thomas ‘Tad’ Lincoln

Thomas Lincoln came into the world on April 4, 1853, in the wake of a family tragedy. His parents, Abraham and Mary, had had three sons — Robert, born in 1843, Eddie, born in 1846, and Willie, born in 1850. But Eddie died in 1850, just before his fourth birthday.

Wikimedia CommonsMary Todd Lincoln with her youngest sons Willie, left, and Tad, right.

Abraham and Mary’s fourth child, then, injected joy into their grieving household. Abraham delighted in his youngest son, who he found “as wiggly as a tadpole.” From then on, “Thomas” went by “Tad.”

Young Tad Lincoln was born with a likely cleft palate, which caused his teeth to grow crooked. As he grew up, he spoke with a pronounced lisp. But Tad didn’t let this get in the way of his mischief. If anything, it added to his rapscallion nature.

Wild, rambunctious, and energetic, Tad and his brother Willie often accompanied their father to his law office. There, they frequently tested the patience of Abraham’s law partner, William Herndon.

The boys, Herndon recalled, would, “take down the books, empty ash buckets, coal ashes, inkstands, papers, gold pens, letters, etc., etc in a pile and then dance on the pile.”

To make matters worse, Abraham delighted in the antics of his sons and rarely disciplined them. Indeed, Herndon wrote, “Lincoln would say nothing, so abstracted was he and so blinded to his children’s faults. Had they sh-t in Lincoln’s hat and rubbed it on his boots, he would have laughed and thought it smart.”

Herndon, on the other hand, wanted to “wring their little necks.”

But Tad’s life changed forever in 1860 when his father ran for president. Though Abraham Lincoln won the election, his victory exacerbated long-existing tensions between the North and the South. Southern states began to secede.

Abraham Lincoln entered the White House determined to keep the Union together. Tad Lincoln just hoped for an adventure. But the Civil War would irrevocably change both of their lives.

Tad Lincoln’s White House Mischief

From the moment the Lincoln family arrived in Washington D.C., the looming crisis of the Civil War consumed Abraham Lincoln. He even entered the city separately from his family — and in secret — because of a plot to assassinate him. Just a month after his inauguration, the conflict began.

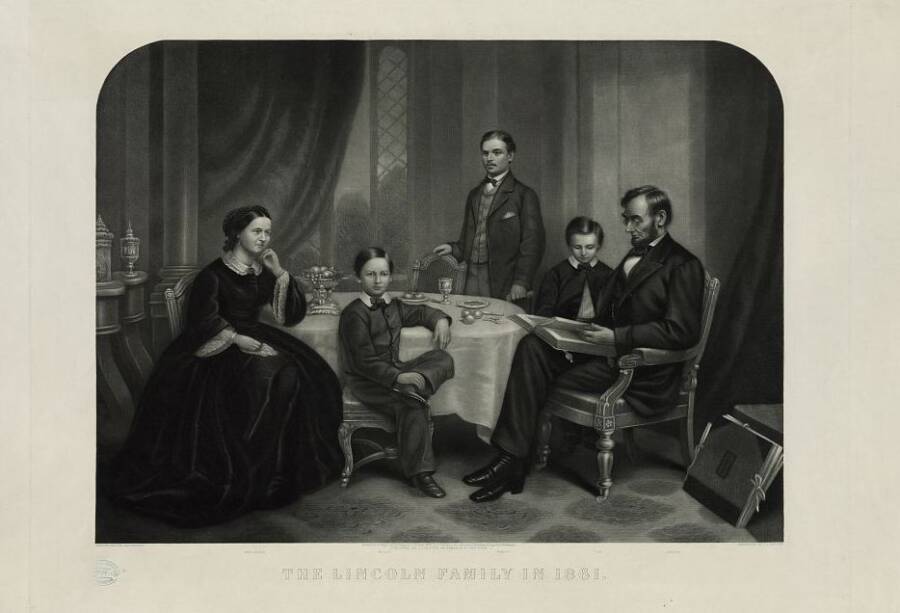

Library of CongressThe Lincoln family in 1861. Painted by F.B. Carpenter ; engraved by J.C. Buttre.

But as Abraham focused on building an army, Willie and Tad found endless outlets for adventure.

“Tad has been trying to make a war-map of Willie, and there are rapid movements in consequence on both sides,” wrote William O. Stoddard, a White House aide. “Peace is obtained by sending them to their mother, at the other end of the building.”

The boys delighted in their life at the White House. They raced through the halls, interrupted important meetings, asked visitors why they’d come to see “paw,” and relished in their pets, which included horses, goats, kittens, rabbits, and dogs.

As their father studied war plans, Tad and Willie climbed to the flat roof of the White House so they could look over the grounds with a spyglass, put on minstrel shows, and constantly rang the servants’ bells. Once, Tad ate all the strawberries for a state dinner, greatly upsetting the White House steward.

To some, the boys were nothing but trouble. One visitor to the White House told a friend he’d just seen the “White House tyrant” — Tad. Cabinet members disliked how the boys interrupted meetings. And Tad had no interest in books — indeed, he may have had a learning disability — which caused a succession of tutors to come and go without success.

But Willie and Tad’s mischief abruptly ended in February 1862, when both boys got sick with typhoid fever.

Tragedies Of The Lincoln White House

As the Civil war intensified, Willie and Tad Lincoln struggled to get well. But only Tad recovered. Willie, at the age of 11, died on Feb. 20, 1862.

“My boy is gone!” cried the president. “He is actually gone.”

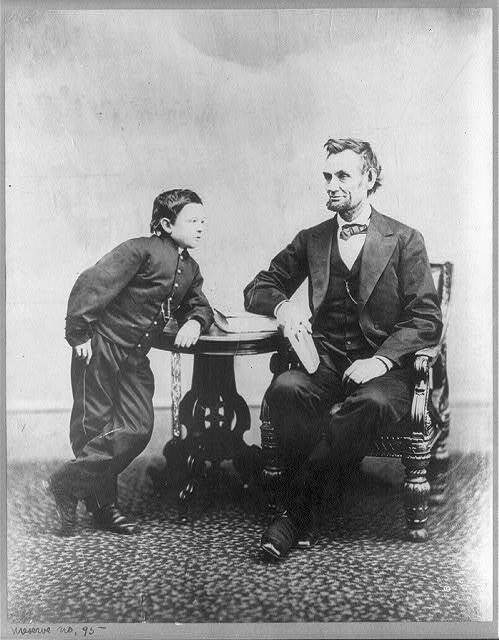

Library of CongressAbraham and Tad grew closer after Willie’s death.

In one fell swoop, Tad Lincoln had lost his best friend, brother, and playmate. Mary Lincoln had lost her “favorite child” and withdrew from public life. In bed for weeks, she delegated care for Tad to others, got rid of Willie’s toys, and forbid the boys’ former playmates from coming to the White House. For Mary, it was too painful to see them.

As a result, Tad and his father drew ever closer.

“The day passed in a rapid succession of plots and commotions, and when the President laid down his weary pen toward midnight, he generally found his infant goblin asleep under his table or roasting his curly head by the open fire-place,” wrote Abraham’s secretary, John Hay.

“The tall chief would pick up the child and trudge off to bed with the drowsy little burden on his shoulder, stooping under the doors and dodging the chandeliers. The President took infinite comfort in the child’s rude health, fresh fun, and uncontrollable boisterousness.”

One White House guard also remembered that the president took great comfort in his youngest son. “I believe he was the best companion Mr. Lincoln ever had,” the guard, William Crook, said. “One who always understood him, and whom he always understood.”

Abraham always made time for Tad, even when he burst into important meetings about the war. The president never disciplined his son for doing so, but instead drew him into his arms.

Though some Cabinet secretaries found this annoying, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton included Tad in the war planning by making him a lieutenant. The boy proudly wore his uniform, and once tried to raise an army out of the White House gardeners and servants.

National ArchivesTad Lincoln in 1864.

“I found it out an hour ago,” his brother Robert complained, “I went to father with it, but instead of punishing Tad, as I think he ought, he evidently looks upon it as a good joke.”

On several occasions, Tad Lincoln even accompanied his father to the headquarters of the Union Army. Decked out in a miniature uniform and on the back of a pony, he endeared himself to the men of the Army of the Potomac.

Just days after Confederate forces abandoned their capital of Richmond, Virginia, the president even brought Tad along to survey the destroyed city. They spent Tad’s twelfth birthday looking at the rubble and waving to raptorious crowds.

It seemed as if the tragedies of the last four years were finally fading. But ten days later, John Wilkes Booth snuck up behind Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theater and assassinated the president.

“They’ve killed him,” Tad cried. “They’ve killed him.”

The Final Years Of Tad Lincoln’s Short Life

Shortly after his father’s death, Tad Lincoln remarked:

“Pa is dead. I can hardly believe that I shall never see him again. I must learn to take care of myself now. Yes, Pa is dead, and I am only Tad Lincoln now, little Tad, like other little boys. I am not a President’s son now. I won’t have many presents anymore. Well, I will try and be a good boy, and will hope to go someday to Pa and brother Willie, in heaven.”

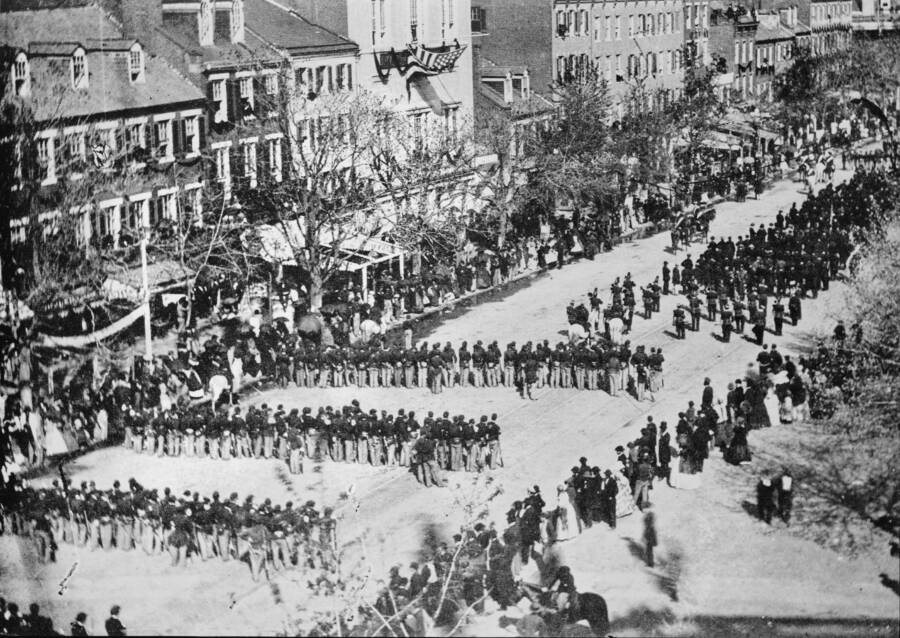

Library of CongressAbraham Lincoln’s funeral was one of the grandest ever seen in Washington, D.C. May 4, 1865.

Mary and Tad stayed in Washington D.C. for a few weeks after the president’s assassination. Although Mary was overcome by grief, Tad attended one of the trials of his father’s assassins. On May 22, they left the White House and moved back to Illinois.

Just as Tad had provided comfort to his father after Willie’s death, he seemed to do the same for his mother. The pair lived in Chicago for a bit, where Tad caught up on his schooling, before sailing for Frankfurt, Germany in October 1868.

“Taddie is like some old woman with regard to his care of me,” Mary raved to a friend in December 1869. “His dark, loving eyes watching over me remind me so much of his dearly beloved father’s.”

But on their journey home in May 1871, Tad Lincoln caught what seemed to be a bad cold. By June, he was seriously ill. And on July 15, 1871, Tad Lincoln died at the age of 18, likely of tuberculosis. His mother was so overcome with grief that she didn’t attend his funeral. Mary Lincoln died exactly eleven years later.

Though tragedy had haunted the Lincoln family, the president’s former secretary John Hay chose to remember Tad as he was at the White House.

“He was so full of life and vigor — so bubbling over with health and high spirits, that he kept the house alive with his pranks and his fantastic enterprises,” Hay wrote in Tad’s obituary. “[He] thought very little of any tutor who would not assist him in yoking his kids to a chair or in driving his dogs tandem over the South Lawn.”

Tad Lincoln, like two of his brothers and his father, died an untimely death. But he left his mark on the Lincoln White House, where his play, mischief, and strong affection for his father helped lift the cloud of the terrible Civil War years.

After reading about Tad Lincoln’s short, tumultuous life, discover the forgotten story of Edwin Booth, the famous actor brother of John Wilkes Booth. Or learn about Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith, the last known Lincoln descendent.