We might not even know the name Mafia today had this fledgling criminal group not narrowly defeated the rival Camorra gang in a bloody war on the streets of New York between 1915 and 1917.

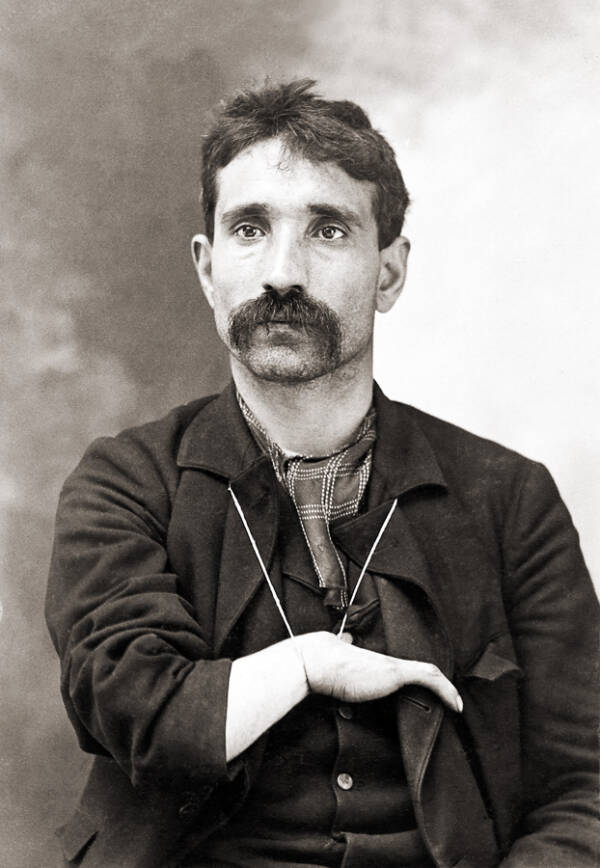

Wikimedia CommonsAlessandro Vollero’s Navy Street Camorra family. At one time, this could have been the organized crime group that became the face of the underworld in the United States.

There are few organized crime groups as legendary and notorious as the Sicilian Mafia. In the 20th century, this infamous criminal organization exerted enormous influence, and even today Cosa Nostra families control sizable criminal empires.

But this dominance wasn’t always assured. In the earliest years of organized crime in the United States, numerous Italian gangs vied for power. In New York, the Mafia’s strongest rival was the Camorra, a considerably smaller group whose roots traced back to Naples.

Secret Societies Come To New York

Between 1880 and 1924, more than 4 million Italian immigrants arrived in the United States. In dozens of cities, Italian communities played host to newly-established Mafia and Camorra families who made money through lucrative “Black Hand” rackets. This involved offering protection to businesses in return for a sum of money.

In New York, the largest gang was the Morello Mafia family of East Harlem, led by Giuseppe “the Clutch Hand” Morello, along with his half-brothers Nick, Vincenzo, and Ciro Terranova.

Wikimedia CommonsGiuseppe Morello, nicknamed “the Clutch Hand” for his physical deformity, was the founder of the first true Mafia family in North America.

Opposing them were two Camorra gangs, one led by Pellegrino Marano in Coney Island and the other led by Alessandro Vollero in a coffee shop on Brooklyn’s Navy Street. The Camorra may have shared a common origin, but they were much less tight-knit than the Mafia, whose close family and regional ties formed nearly unbreakable bonds.

For nearly a decade, these rival factions had left each other alone to their respective trades. The Mafia ran protection for groceries, ice, and coal, which every Italian neighborhood needed, thus representing huge profits with tens of thousands of customers.

Library of CongressMulberry Street in Manhattan, long the center of the Italian community in New York, contained many of the back alleys and tenements where gambling, narcotics, and other criminal enterprises were played out.

Gambling, prostitution, and drugs were left for the Camorra gangs. These were restricted to back rooms and quiet alleys where only a small amount of clientele could be counted on. But by 1915, tensions had come to a head over who would control it all.

The Camorra Senses Weakness

Trouble began in 1913 when Nick Terranova, who’d been the boss of the Morello family since Giuseppe’s imprisonment in 1910, tried to wrest control of gambling in Manhattan from kingpin Joseph DiMarco.

DiMarco tried and failed to have Nick killed in retaliation, and in turn Nick had DiMarco shot through the neck. His life was saved afterward through hours of intense surgery.

The Mafia don sent his men to try again, this time firing at DiMarco with shotguns as he laid back in a barber’s chair. Again, he survived.

Insulted and desperate to preserve their fearsome reputation, the Terranova brothers turned to the Camorra. Finally, in the summer of 1916, gunmen employed by Vollero and the Navy Street Camorra family shot DiMarco 10 times during a backroom poker game, killing DiMarco and cementing the Morellos’ control of gambling on the East Side.

Wikimedia Commons Camorra members are taken to court. Founded in 1820, this group was older than the Mafia, but never achieved the same level of organization or success in North America.

Pellegrino Marano had hoped to form a syndicate of Italian crime groups in New York to share the wealth and reduce tensions. As his right-hand man Tony “the Shoemaker” Paretti put it:

“If we could all get together and agree, after this job is done, we would all be wearing diamond rings, and we would get all the graft.”

But the Morellos had no intention of sharing with the Camorra. Instead, they basked in their newfound dominance, while the Camorra bosses grew quietly furious at being shut out.

The Mafia-Camorra War

Marano struck first. The Terranova brothers and three other Mafia captains were invited to Navy Street, under the false pretense of discussing an amicable way to divide their rackets.

In preparation for the meeting, Marano’s men prepared bullets smeared with garlic and pepper, believing that this would infect their rivals’ wounds and ensure their deaths long after the shootout.

When only Nick and one other boss showed up, Marano went ahead with the plan anyway, murdering both of them. Blindsided, the Mafia was still in a state of disarray and confusion when Marano followed up this ambush by quickly killing six more Morello soldiers.

The Camorra, only about 40 strong, had managed to throw the Mafia out of the biggest rackets despite the Mafia’s numbers and wealth. But when they tried to force the gamblers and other merchants to pay tribute to them, they came up against unexpected resistance from those who suspected the Terranovas would return.

The Camorra had to accept either nothing, or whatever the merchants felt like paying. Meanwhile, Vollero and Marano desperately hunted the Mafia bosses, realizing that if they didn’t kill them, they would lose everything.

An Informant Turns The Tide

But it was the testimony of an embittered Camorra member who would bring about the end of the war and the downfall of the Camorra.

Ralph “The Barber” Daniello, a small-time member of the Navy Street gang, had escaped to Reno with his 16-year-old girlfriend after being acquitted of robbery and abduction charges.

When Vollero refused to pay him after his money had run out, he penned an angry letter to the NYPD’s Italian Squad offering to sell information.

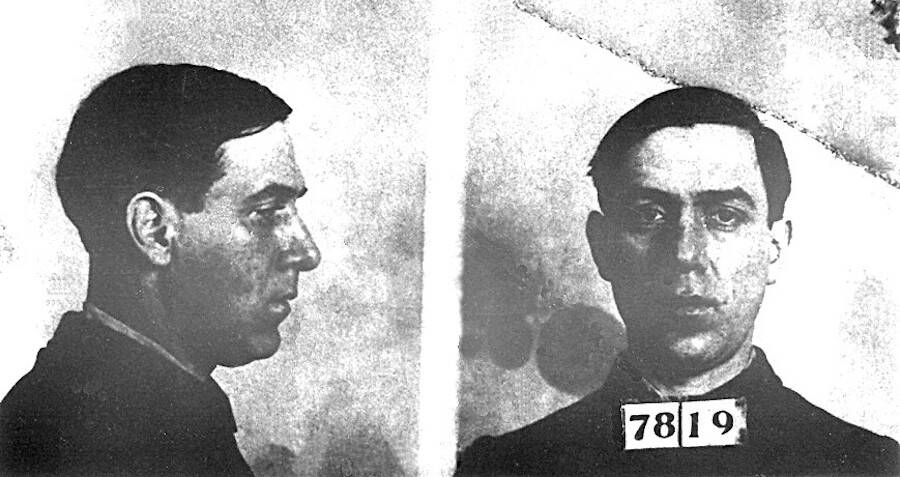

Wikimedia CommonsRalph “The Barber” Daniello was the first mass informant on the mob in American history, and his testimony to the NYPD’s Italian Squad helped topple the Camorra.

Over the span of nearly two months, Daniello told the police everything he knew, solving almost two dozen murders and providing leads for hundreds of open cases. At the time, it was the biggest mob confession in history, and the effect was immediate. Within weeks, dozens of Camorra members were arrested, while the Mafia’s lawyers helped them survive trial.

The war was over. Their rivals destroyed, the Morello family was left to cement its place as the reigning crime syndicate of New York City.

The Effect On Pop Culture And American Crime

The Mafia-Camorra War was a watershed moment in the history of organized crime. Within a few years of its conclusion, the Mafia would become the quintessential American mob in the popular imagination of Americans, a dreaded yet titillating secret society with a distinct mythology.

The Morello family would eventually become the Genovese crime family, one of New York’s legendary Five Families and to this day one of the most significant Italian-American criminal organizations.

Wikimedia CommonsAlessandro Vollero, boss of the Navy Street Camorra gang, after his arrest. After a long prison sentence, he was exiled to his hometown of Gragnano, near Naples, Italy.

The bonds of loyalty, the rapid and bloody nature of mob warfare, and the colorful nicknames and rackets of the rival gangs created a vivid picture in the minds of ordinary citizens.

In later years, films such as The Godfather and Goodfellas and TV series like The Sopranos would become iconic portrayals of crime, all of which might have been about a very different group if only The Barber’s pleas for payment had been answered by the Camorra back in the summer of 1917.

After learning about the fateful Mafia-Camorra War, you can read about the architect of the national Mafia conspiracy, Lucky Luciano. Then, read more about the death of Joe Masseria, one of the last old-school dons.