The Warren Commission concluded in 1964 that the same "magic bullet" that struck President Kennedy proceeded to slice through multiple layers of skin, bone, clothing, and muscle tissue. The crazy thing is, it's not as crazy as it sounds.

On Nov. 22, 1963, Lee Harvey Oswald fired off a shot with enormous repercussions. The bullets that left his bolt-action Carcano M 91/38 rifle from a sixth-floor window of the Texas School Book Depository in downtown Dallas killed the president of the United States, and — depending on who you ask — one of them defied the laws of physics as we know them.

On Oswald’s first or second shot, a 6.5-millimeter bullet hit President John F. Kennedy in the back, to the right of his spine, and then left his body through the front of his neck. It exited below his Adam’s apple, hit his necktie knot, and continued into Texas Gov. John Connally’s back and shattered his fifth right rib bone.

After exiting Connally’s chest, the bullet entered the governor’s right wrist — breaking yet another bone — before exiting and burrowing into his left thigh. Oswald’s third shot was the clincher, hitting Kennedy square in the skull and changing the course of history forever. One of the shots — either the first or the second — missed.

At least that was what the official, government-sanctioned Warren Commission concluded in its September 1964 report.

With a growing distrust in the government during the mid-to-late 1960s, and a flurry of books suggesting there was an internal conspiracy at play to kill the president, the single-bullet (or magic bullet) theory garnered as many detractors as genuine believers.

Wikimedia CommonsJohn F. Kennedy, Jacquelin Onassis, and John Connally in the Lincoln limousine motorcade moments before the President’s assassination. Nov. 22, 1963. Dallas, Texas.

The Warren Report was upheld in 1979, though the single-bullet theory — which some call the “magic bullet theory” — remains one of most hotly contested claims the government has ever made.

The theory was central to bolster the government’s assertion that there was only one shooter and that that shooter was Lee Harvey Oswald, since Oswald’s rifle wasn’t fast enough to shoot multiple bullets in the timeframe when both Kennedy and Connally suffered their initial injuries.

Let’s take a look at what the official narrative specifically proposed, and outline some of the most pertinent facts that either support or refute its most important point: that one bullet injured both President Kennedy and Gov. Connally.

The Magic Bullet Theory

Critics of the single-bullet theory have dubbed it the “magic bullet theory,” mostly because of decades-old misconceptions surrounding the relative placement of Kennedy’s and Connally’s bodies in their shared, open-air limousine.

After a quick Google search, you’ll find all sorts of squiggly-lined drawings and diagrams showing the bullet’s supposedly physics-defying path from Kennedy’s mid-back, up to his Adam’s Apple, over to Connally’s back, up to his wrist, and straight down and over to Connally’s left thigh.

This interpretation isn’t limited to the depths of the internet.

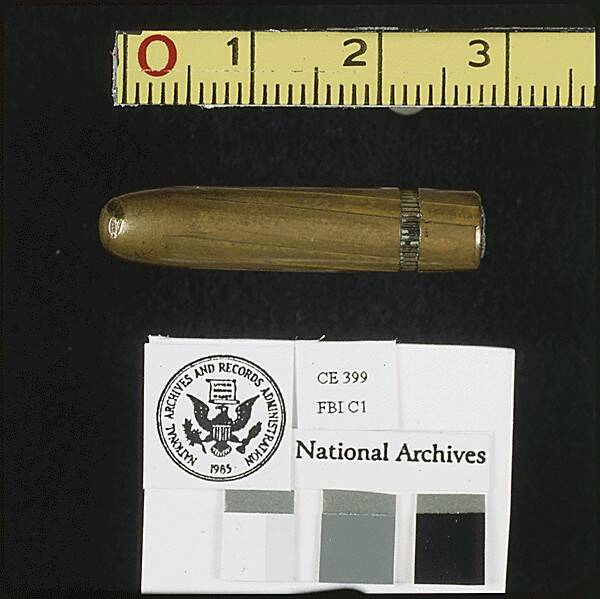

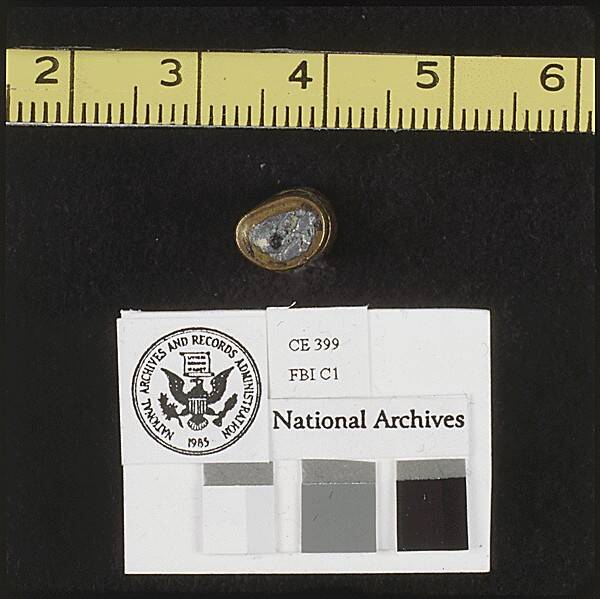

In Oliver Stone’s 1991 film, JFK, for example, a New Orleans district attorney, played by Kevin Costner, reenacts the shooting in front of a rapt jury. With a squiggly-lined diagram behind him, he describes Exhibit 399, or CE 399 (the “magic bullet’s” official name) turning “right, then left, right, then left” before making a “dramatic u-turn” in order to hit all of Kennedy’s and Connally’s points of injury. The blockbuster film was nominated for eight Oscars and reignited the magic bullet debate for a new generation.

But CE 399’s supposed twists and turns are based on a gross misconception of how Kennedy and Connally were situated in their limousine.

In the JFK courtroom scene, the men standing in for the president and the governor are seated in chairs that are the same height, one directly in front of the other. Given that layout and the placement of the two men’s injuries, it seems like the bullet would have had to defy gravity to hit all the right marks.

This is not how the limousine’s seats were laid out, however. In reality, Connally’s seat was lower and further to the left. And based on photographic and video evidence, we know the president was seated all the way to the right of his back seat, his arm resting on the frame of the car.

And so the bullet didn’t have to turn right and left over and over again. In fact, if you place Kennedy’s and Connally’s bodies correctly, their injuries form a practically straight line.

What’s more, magic bullet theorists point to the fact that the place where the bullet entered through Kennedy’s jacket was supposedly lower than his neck exit wound. There’s no way a bullet shot from a gun pointing downwards would suddenly shoot up while in the president’s body.

But that point is also based on faulty evidence. Photographs from the moments before the shooting show that Kennedy’s jacket was bunched up at his neck, and so the entry point on his coat is in fact lower than where the bullet actually entered his back.

Thus, the up-and-down, left-to-right see-sawing that the “magic bullet” supposedly had to pull off in order to make all of Kennedy’s and Connally’s injuries didn’t happen at all. In fact, it’s possible that CE 399 traveled in a virtually straight line, from Kennedy’s back all the way to Connally’s thigh.

Subsequent Tests

The investigation into Kennedy’s death and the single-bullet theory didn’t conclude with the Warren Commission. The theory would be tested again and again — both by the government and by independent forensics enthusiasts — over the following decades.

Among these tests was a confidential March 1965 report, issued by ballistics experts at the U.S. Army’s Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland. Using the same type of rifle and bullets that killed Kennedy, the scientists tested the theory on a slew of gelatin blocks, human skulls, and goat skins to recreate the effects of body parts on a bullet’s velocity and trajectory.

Wikimedia CommonsThe “magic bullet” did look rather pristine after hitting two people — some say it was too pristine.

While their tests confirmed that “the bullet that wounded the president had enough remaining velocity to account for all of the governor’s wounds,” they found it “more difficult to draw a firm conclusion” on whether the two men were actually injured by the same bullet. According to their tests, Gov. Connally’s back and chest wound “could have been produced by either the shot that hit President Kennedy in the neck or by a separate shot.”

“If it was a separate shot,” the report concluded, “then the bullet that hit the president in the neck must be accounted for.” They recommended that “a very careful reenactment of the assassination be done” to see whether it was possible that the bullet the struck Kennedy in the back could have “missed the car and its occupants completely.”

It’s not clear whether such a reenactment was ever performed, though the House Select Committee on Assassinations confirmed the single-bullet theory in a 1979 report.

Still, the committee itself muddied the waters when it concluded in that same report that four — not three — bullets were fired, and that one of those bullets came not from the Texas School Book Depository, but from the so-called “grassy knoll,” an open part of Dealey Plaza the president’s motorcade drove through when he was shot and killed.

The committee based its conclusion on an audio recording from a Dallas police officer. An acoustical analysis of the tape identified four gunshots, with the echo pattern indicating that one of those shots came from the direction of the grassy knoll.

Wikimedia CommonsThe base view of the controversial piece of evidence, labeled “CE399.” While it did appear to have been fired, some experiments to replicate the damage it would’ve incurred didn’t match up.

The National Academy of Sciences performed its own analysis of the tape after the committee issued its report and found that the House’s audio analysis was riddled with flaws. There was no evidence of a fourth gunshot or a second shooter.

But the damage to public perceptions had already been done.

Aftermath Of The Assassination

President Kennedy was pronounced dead at Parkland Memorial Hospital at 1 p.m. that day. Lee Harvey Oswald was found and arrested less than an hour later.

Oswald told reporters that he didn’t shoot anybody. He famously called himself a “patsy” two days before nightclub owner and police informant Jack Ruby murdered him on live television — silencing him for good.

Wikimedia CommonsLyndon B. Johnson was sworn in as the 36th President of the United States a little over an hour after Kennedy was shot. A distraught Jacqueline Kennedy stood beside him as her husband’s body was loaded onto the plane.

While Ruby himself claimed he was acting out of vengeance for the Kennedy family, and that killing Oswald had nothing to do with a broader conspiracy involving shadowy players within the government — that secondary incident left many suspicious and dubious to this day.

With the alleged lone gunman dead, the possibility of having him divulge any information contradicting the single-bullet theory was gone, as well.

Skepticism Surrounding The Single Bullet

There was hardly widespread acceptance of the Warren Report’s findings — not even within the federal government. In 2013, it was revealed that President Kennedy’s own brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, considered the Warren Report a “shoddy piece of craftsmanship.” Half of the Warren Commission was skeptical of the single-bullet theory.

According to journalist Philip Shenon, who wrote a book about the Kennedy assassination, Arthur Schlessinger Jr., a friend of the Kennedys, said Robert Kennedy was convinced the Warren Commission’s “lone gunman” story was false.

Schlessinger said that in December 1963, Robert Kennedy told him that he feared Oswald was merely “part of a larger plot, whether organized by Castro or by gangsters.”

He added that two years after the Warren Report was published, Robert Kennedy remained convinced that there was a conspiracy, and wondered out loud “how long he could continue to avoid comment on the report — it is evident that he believes it was a poor job.”

Modern Technology And More Support For The Magic Bullet Theory

Debate around the magic bullet theory has substantially shifted in recent years, thanks to the advent of modern 3D-simulation technology.

About 50 years to the day after Kennedy’s assassination, one father-and-son forensics team used these technological advances to put the single-bullet theory to a more rigorous test, assessing the trajectory of Oswald’s bullet more precisely than ever before.

“[We can envision] crime scenes more thoroughly, more completely than we ever had had the capability to do,” said Michael Haag in an interview with CBS. “So we walk away from the crime scene with more information and we can then examine the crime scene over and over again later on, on a computer.”

What the duo found, according to Luke Haag, was that the one bullet could “easily” have gone through two people “if you understand how this particular unusual bullet behaves and what [it] does after it leaves Kennedy’s body.”

“People didn’t understand then and don’t understand now,” he said. “It will go through a lot of material, and then when it comes out it starts tumbling…and that’s how it hit Connally. It’s like a badly thrown football. It normally flies true and straight.”

“When this bullet emerged from Kennedy — our any ballistic medium…it’s now yawing and tumbling. The entry wound in Connally is very important because it’s the consequence of a yawed bullet, so it had to be a destabilized bullet from somewhere.”

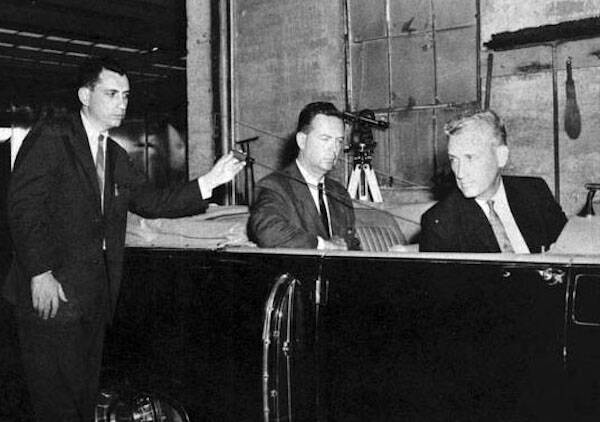

This informed reevaluation has, of course, been starkly different than prosecutor Arlen Specter’s presentation of the bullet’s trajectory in court decades earlier. Using a mere rod and two adult males in a replica of the Lincoln limousine, it was simply too primitive for doubts to persist in comparison to Luke and Michael Haag’s work.

When asked if he thought one bullet could do the damage witnessed in Dallas that day in 1963, Michael Haag said, “As far as the neck wounds to the president and the wounds to John Connally, absolutely.”

He added that the argument of Oswald simply not being a good enough shooter to pull off the was yet another unfounded misdirection. According to Luke Haag, Oswald’s rifle, wasn’t as inaccurate as so many detractors claim.

“If the bore in the rifle is good, it’s a good shooter and it was a good shooter,” he said, “unfortunately for President Kennedy.”

“The question about multiple shots, the behavior of the bullet that goes through Kennedy and becomes the single bullet theory became controversial because, again, people didn’t evaluate it. They didn’t understand it, and they hadn’t looked at it then and few have looked at it now.”

John McAdams, a political science professor at Marquette University in Wisconsin and an expert on the Kennedy assassination would likely agree with the Haags.

Wikimedia CommonsArlen Specter of the Warren Commission tries to reproduce the trajectory of the single-bullet theory. May 24, 1964.

“Thomas Canning was a NASA scientist who studied the single-bullet trajectory for the House Select Committee on Assassinations,” he wrote on his website, referring to the theory being upheld by a congressional committee in 1979.

“The result was an alignment that showed the bullet leaving Kennedy’s throat to strike Connally in the back near the shoulder — which is where Connally was actually struck.”

McAdams also studied a computer recreation of the bullet’s trajectory from the 1990s.

“Failure Analysis Associates, in work done for a 1992 mock trial of Lee Harvey Oswald for the American Bar Association, used 3-D computer animation and modeling techniques to research the bullet trajectory, and concluded that the single bullet trajectory works.”

“We want to think there’s more to it than a loner loser deranged Marxist who hated his country and took an opportunity,” said Luke Haag. “There’s got to be more to it than that. [Vincent] Bugliosi [the famous prosecutor] has a wonderful statement, ‘A peasant cannot strike down a king.'”

After learning about the arguments for and against the Warren Commission’s “magic bullet theory,” take a look at 39 haunting Kennedy assassination photos most people have never seen. Then, learn about the shocking assassination of Inejiro Asanuma.