After her brother was nearly buried alive, 18th-century Englishwoman Hannah Beswick feared a similar fate — so her doctor mummified her and displayed her blackened face inside his grandfather clock.

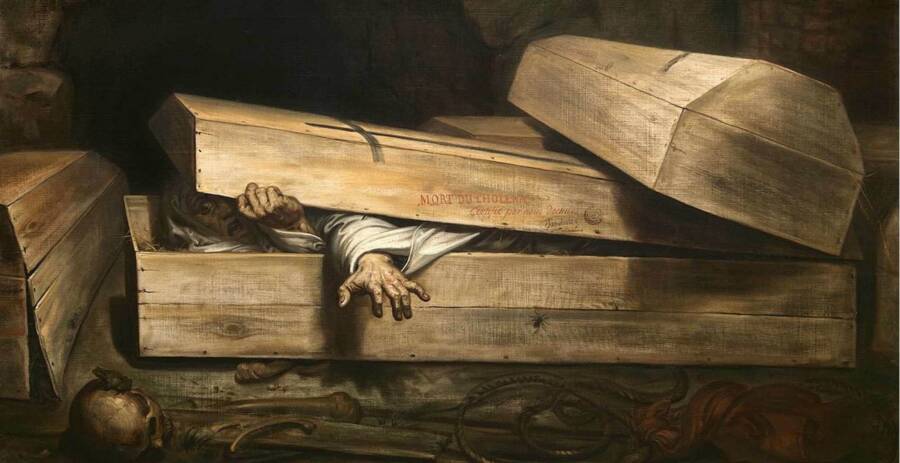

Wikimedia CommonsAntoine Wiertz’s ‘L’Inhumation précipitée’ (or “The Premature Burial”) from 1854 depicted real fears commonly shared in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Eighteenth-century Englishwoman Hannah Beswick was terrified of being buried alive. This fear, called taphophobia, was common in her time, as doctors with little understanding of comas would declare people dead prematurely.

But Beswick’s reasons were much more personal.

According to the BBC, Beswick — who hailed from Lancashire county, north of Manchester — inherited a sizable fortune from her parents.

Born in 1688, the pathologically petrified woman lived a wealthy yet nondescript life. Her fame came about after her death.

She had witnessed her brother, John, being nearly buried alive after his eyelids flickered at his own funeral. He soon regained consciousness and lived many more years.

This led Beswick to make some rather curious choices while alive. According to Matt Cardin’s Mummies Around the World, these choices led to her mummification after her death in 1758.

Displayed for more than a century at her surgeon’s home and at the Museum of the Manchester Society of Natural History, she was finally buried in 1868. Since her death and forever more, she has been known as the Manchester Mummy.

Buried Alive: An 18th Century Fear

There are at least four stories by literary horror master Edgar Allen Poe that revolve around the fear of premature burial. According to Historic UK, there was an enormous uptick in collective concern about the possibility this could occur to someone. It was even rumored that Robert E. Lee’s mother had been buried alive.

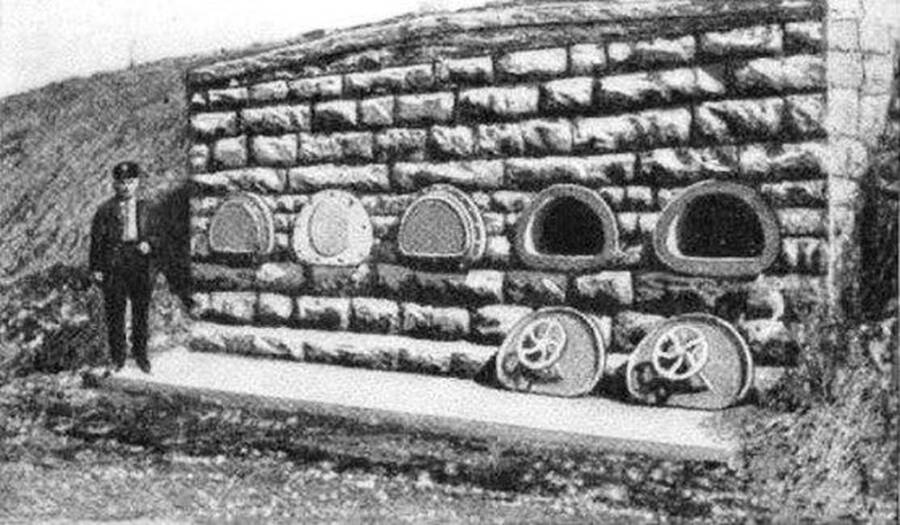

Wikimedia CommonsThis 1890 burial vault was designed specifically to prevent premature burials. A person could survive in one of the vaults for hours, and certainly long enough to open the cover by turning the hand wheel.

Though that turned out to be legend, the fear was widespread enough for these types of stories to be commonplace.

Thus, new methods and preventive systems were created to assuage a terrified populous. In 1896, two anti-vaccinationists founded the London Association for the Prevention of Premature Burial. The two Englishmen, William Tebb and Walter Hadwen, claimed that 16,000 people were buried every year without the proper medical certification that they were indeed dead. (Sir Matthew White Ridley, a statesman, rebutted: “The number of uncertified deaths in 1896 was 11,464; and there has been a steady decrease for many years past.”)

For some, live burial was a conspiracy theory or at the very least an issue of little concern. But for others, it was a source of overwhelming anxiety.

In 1897, Count Michel de Karnice-Karnicki patented his safety coffin, which would ring a bell and supply air upon the detection of movement. But his invention was about 150 years too late for Hannah Beswick.

Thus, she placed her trust in Dr. Charles White — the same man who declared her brother was still alive.

Unfortunately for Beswick, Dr. White’s curiosities involved mummifying the terrified woman after her death — and displaying her dead body to countless visitors for years before letting her rest.

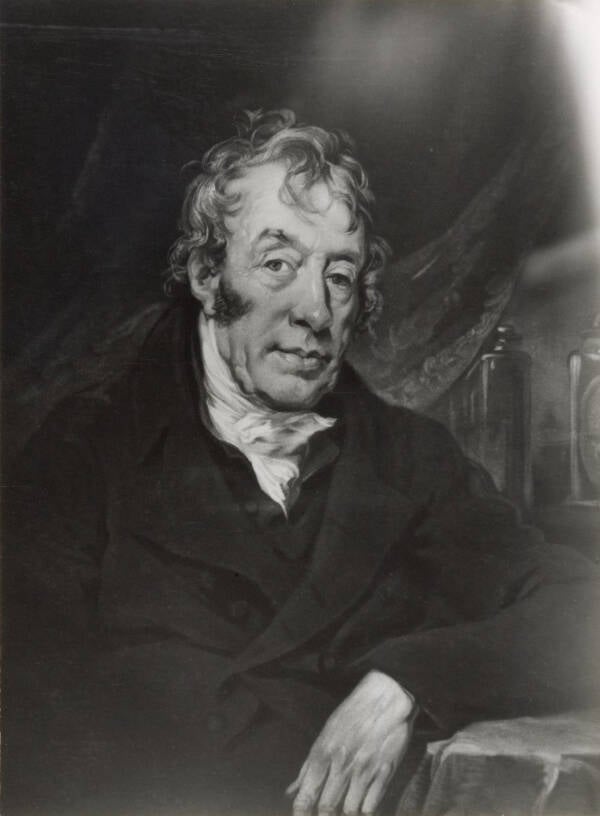

Wikimedia CommonsHannah Beswick turned to her family physician, Dr. Charles White, to ensure she was dead before they buried her. He went a step further and embalmed her for public viewing, instead.

Hannah Beswick: Becoming The Manchester Mummy

Beswick asked her doctor to verify she was dead before putting her in the ground, as well as check on her periodically for signs of life, but little else is known about their agreement.

By the time she died in February 1758, she had failed to include post-mortem instructions in her will. And so White decided to embalm her.

Whether she knew about Dr. White’s personal collection of mummies — which included the skeleton of Thomas Higgins, the infamous highway man of Knutsford — is uncertain. And we don’t know exactly how White embalmed her, we do know that he studied under anatomist William Hunter.

According to Jolene Zigarovich’s Preserved Remains: Embalming Practices in Eighteenth-Century England, Hunter’s technique involved injecting the veins and arteries with a combination of turpentine and vermillion before the person’s organs are removed and placed in water to clean.

After squeezing as much blood from the corpse as possible and washing it with alcohol, Hunter would fill the body cavities with camphor, nitre, and resin before sewing up all of its openings.

According to legend, White opted to put her embalmed and mummified corpse — with all but her face wrapped in cloth – on display in an old grandfather clock. Visitors flocked to his home, where he’d pull back a curtain to reveal Beswick’s embalmed face.

But it was only after Dr. White died himself in 1813, at age 84, that Beswick’s corpse changed locations — and garnered its ominous nickname.

The Manchester Mummy On Display

Bequeathed to friend and colleague Dr. Ollier, the body was donated in 1828 to the Manchester Natural History Society. It was put on display by the entrance alongside two mummies from Egypt and Peru. It was here that the title of Manchester Mummy was cemented.

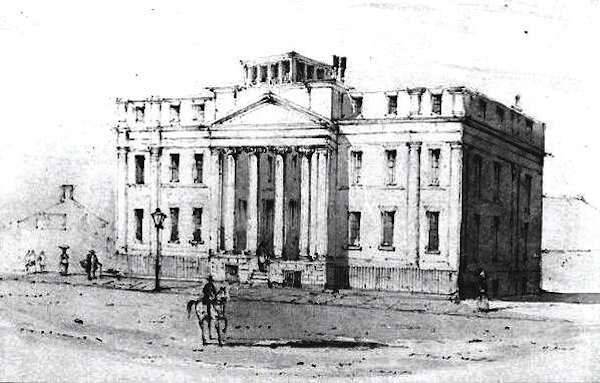

Wikimedia CommonsA drawing of The Museum of the Manchester Natural History Society as it was around 1850. Hannah Beswick’s mummified body was displayed here until 1867.

In 1867, the Society donated it to Owens College (now the University of Manchester). There are no known photographs or drawings of the Manchester Mummy, and so the only accounts we have of her appearance come from the writings of those who witnessed her first-hand, such as local historian Philip Wentworth:

“The body was well preserved but the face was shriveled and black. The legs and trunks were tightly bound in a strong cloth such as is used for bed ticks [a stiff kind of mattress cover material] and the body, which was that of a little old woman, was in a glass coffin-shaped case.”

With waning interest and no doubt Beswick was officially dead, it was decided that she deserved to rest. She was buried at Harpurhey Cemetery on July 22, 1868, with the permission of Manchester’s bishop and an order from the government.

Her burial 110 years after death wasn’t the last time people saw Beswick, however. According to Mysterious Universe, legend has it that she hid a sizable chunk of her fortune when Scottish rebel Bonnie Prince Charlie arrived in Manchester in 1745 and threatened to take over the city.

She took that secret to the grave with her, but allegedly told workers living in her converted home where to find it — from beyond the grave. One worker, a weaver, allegedly found a stash of gold in the walls.

Others have reported seeing a shadowy female figure in black silk, floating through the walls of her family’s estate of Birchin Bower. Whether true or not, Hannah Beswick certainly managed to avoid her foremost fear: She was buried well after she died — more than a century, in fact.

After reading the spooky story of Hannah Beswick, the Manchester Mummy, read about the Japanese monks who mummified themselves while still alive. Then, learn about the Inca ice maiden, perhaps the most well-preserved mummy in human history.