Maria Rasputin escaped death in Russia and went on to become a lion tamer and author — but was she really the Grigori Rasputin's daughter?

Her father was one of the most controversial figures in Russian history. As a little girl, she played with the Romanov daughters. And when imperial Russia fell, this girl — Maria Rasputin — fled the country and wound up in Los Angeles after a long career in lion taming and cabaret.

Indeed, while popular accounts say that the Rasputin family name ended with the infamous Grigor Rasputin’s death, Maria Rasputin’s life proves otherwise.

Bettmann/CORBISMaria Rasputin in March 1935.

In fact, she took the family name to new heights — if she was, in fact, his daughter.

Maria Rasputin’s Early Life

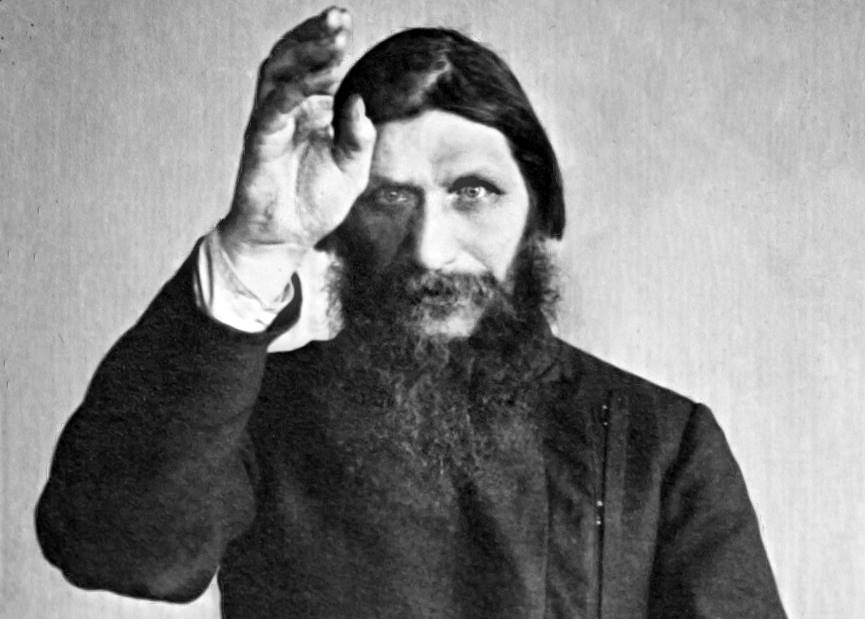

Public DomainGrigori Rasputin (left) — mystic and self-styled holy man who had a magnetic influence over Tsar Nicholas II and his wife, Alexandra — sits among a group of his followers, circa 1911.

In 1898 — or possibly 1899 — a peasant family welcomed their newborn child, Matryona Rasputin, into the Siberian village of Pokrovskoye. The little girl would later change her name to Maria Rasputin in order to better climb the social ladder in Russia’s capital.

In the summer of 1914, a woman named Khioniya Guseva would attempt to assassinate Maria Rasputin’s father, Grigori. This event would spark a dramatic change in her father’s behavior, one which would set the path for his ascendence to the “Mad Monk” of Russia.

Following the assassination attempt, Grigori Rasputin began to drink more intensely (mostly dessert wines, which can have a very high alcohol content) and became heavily involved in the Russian Orthodox faith. He learned a great deal about magnetism and its uses in the human body, which would lay the foundation for what became his famous “healing practices.”

Rasputin thus became a sensation in Russia after using his supposed healing abilities to treat the son and heir of Tsar Nicholas Romanov II, Alexi, who had a blood disorder known as hemophilia. Somehow — and it’s not clear how — Rasputin was able to stop Alexi’s bleeding, leading the Tsar and his wife to believe that only Rasputin could keep Alexi alive — and thus secure the future of the Romanov dynasty.

Wikimedia CommonsGrigori Rasputin.

Rasputin immediately became a fixture in the House of Romanov — as did his young daughter, Maria, who was about the same age as the Tsar’s daughters. Maria Rasputin wrote in her diary during these years that the Romanov girls — Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia — were elegant but very cloistered from the rest of the world.

As such, Maria fascinated the Romanov sisters, as she had seen the world beyond palace walls and had many stories to tell. The Romanov daughters, as well as their mother and father, all became increasingly dependent on the apparent healing powers of Rasputin, but the rest of Russia was wary of his closeness to the Tsar. Many suspected that he held too much influence over matters of state, which contributed to the growing discontent among Russians that would eventually lead to the downfall of the Romanov family.

It was no surprise, then, that a group of aristocrats banded together in 1916 to kill Rasputin — a task that proved to be phenomenally difficult. Rasputin survived poisoning, shootings, and stabbings, and only died when he was left to drown in the frigid waters of the Neva River.

Maria Rasputin would identify the body of her fallen father via a galosh stuck to the bridge from which his killer had presumably thrown him. She later wrote of his funeral that:

“Many places in the little chapel were empty, for the crowds that had knocked at my father’s door while he still lived to ask some service of him neglected to come and offer up a prayer for him once he was dead.”

After The Mad Monk’s Death

Public DomainEmpress Alexandra Feodorovna with Grigori Rasputin, her children, and a governess.

For a time, Maria Rasputin and her sister remained with the Romanovs. But when it became clear that they, too, were at risk, Empress Alexandra gave them 50,000 rubles and essentially told them to run for their lives. “Go my children, leave us, leave us quickly, we are being imprisoned,” Rasputin recalled that the Empress told them. The Bolsheviks would kill the entire Romanov family soon after.

Rasputin heeded the Empress’ advice and — with the help of Boris Soloviev, who would later become known as one of the men who attempted to cash in on the Romanovs’ execution by hiring girls to pretend to be the last-surviving Romanov — fled to Europe. The two wed and had two daughters: Tatiana and Maria, named for the Grand Duchesses.

At this point, the girls and Soloviev were all Mari Rasputin had: the entire Romanov family had died, her mother and brother had disappeared into Soviet labor camps in Siberia, and her sister had died under mysterious circumstances (some say she starved, others believed she was poisoned). In 1926, when Soloviev died of tuberculosis, Maria Rasputin had to find a way to support herself and her daughters.

The only thing she knew she could use was her name.

Planet News Archive/SSPL/Getty ImagesMaria Rasputin with elephants in London.

Although she had never danced before, her famous last name led to a job offer in cabaret. Rasputin accepted the position without hesitation and took lessons to refine her performance, before quite literally running away to join the circus in 1929.

Of her time in cabaret, Rasputin wrote that she danced to:

“The tragedy of my father’s life and death, and be brought face to face on the stage with actors who were impersonating him and his murderers. Every time I have to confront my father on the stage a pang of poignant memory shoots through my heart, and I could break down and weep.”

Maria Rasputin then traveled throughout Europe and readily used her name in order to get more gigs. Once she became trained as a lion tamer, her career really took off.

Rasputin often billed herself as “performing magic over wild beasts just as her father dominated men” or “the daughter of the famous mad monk whose feats in Russia astonished the world,” and once told an interviewer who asked her if she minded being in a cage with animals, “Why not? I have been in a cage with Bolsheviks.”

When the circus troupe went to America, customs officials denied Rasputin’s daughter entry. They stayed in Europe for the rest of their lives, but Rasputin remained in the United States even after she retired from the circus — something she did in 1935 after being mauled by a bear.

Eventually, Rasputin married a man named Gregory Bernardsky, a former member of the White Russian Army whom she’d known in childhood and had inexplicably run into again in Miami. Although their marriage didn’t last (they divorced in 1946) Rasputin was able to become a U.S. citizen.

She then worked as a riveter during World War II and remained in factory work until 1955. During that decade’s Red Scare, some speculated that Maria was a communist, an accusation which horrified her.

Unequivocally denouncing that claim in 1948, Maria Rasputin wrote a letter to the LA Times wherein she stated that:

“I am constantly being persecuted and branded a communist due to my name being Maria Rasputin, daughter of Gregory Rasputin, known as the ‘Mad Monk of Russia.’ I left Russia 28 years ago and am now a naturalized American citizen, for which privilege I thank God every night, as I love the United States of America from the bottom of my heart. I wish to announce publicly that I am not a communist even though my name is Maria Rasputin, daughter of Gregory Rasputin.”

In Los Angeles, the retired lion tamer subsisted on Social Security benefits, teaching Russian, and babysitting. Of course, Rasputin did occasionally give interviews to the press (like in 1968 when she claimed to be a psychic and said that Betty Ford spoke to her in a dream) and wrote several books about her father.

Rasputin pointed out, however, that she had not wished to make a career of book writing, but that she had done so only in order to clear her father’s name:

If I thought myself capable of undertaking a literary career I should not today be struggling to earn my daily bread as a trainer of wild animals… it is my desire to consecrate myself to a task, direct the whole of my life towards one goal, that of giving back to my father his true character.

Maria Rasputin’s Greatest Act?

Public DomainMaria Rasputin.

Maria Rasputin’s last book, Rasputin: The Man Behind The Myth was published in 1977, shortly after she died. Rasputin wrote the book with Patte Barham, and it included many of her own memories and diary entries from her childhood in Russia — though some were not convinced she was telling the truth.

And that’s not necessarily without reason. In the years directly after the execution of the Romanovs, many came forward claiming to be a surviving daughter of that family (usually Anastasia, the youngest).

What many don’t know is that after Grigori Rasputin’s daughters escaped the Russian capital, many came forward claiming to be his heirs, too. This was easy to do since no one is exactly sure how many children he had out of wedlock.

Maria Rasputin, however, purported to be the real deal — indeed, she based her entire career on it.

When Maria Rasputin died, The New York Times published her obituary, calling her a “dancer and circus performer who contended that she was a daughter of the ‘Mad Monk’ Grigori Rasputin,” leaving many to wonder if maybe her name had been her greatest performance of all.

Intrigued by this look at Maria Rasputin, the reported daughter of Grigori Rasputin? Next, check out the Romanovs’ final days — in stunning color. Then, delve into the history of Rasputin, the Mad Monk himself.