Marie Curie's biography presents an inspiring portrait of a woman who overcame poverty and misogyny to make Earth-shattering scientific discoveries.

Marie Curie is a woman of many outstanding firsts. She was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize in physics in 1903. Eight years later, she became the first person and only woman to win the Nobel Prize twice. As if that wasn’t impressive enough, her two wins also cemented her as the only person to have ever won the Nobel Prize in two different scientific fields — physics and chemistry.

But who was Marie Curie? Read on to get a glimpse into the life of one of the greatest scientists of all time.

Marie Curie’s Fragile Childhood

Wikimedia CommonsMarie Curie when she was 16 years old.

Born Maria Salomea Skłodowska, she came into the world on Nov. 7, 1867, in what is now Warsaw, Poland. At the time, Poland was under Russian occupation. The youngest child of five, Curie was raised in a poor family, her parents’ money and property having been taken away due to their work to restore Poland’s independence.

Both her father, Władysław, and her mother, Bronisława, were proud Polish educators and sought to educate their children in both school subjects and their oppressed Polish heritage.

Her parents eventually enrolled the children in a secret school managed by a Polish patriot named Madame Jadwiga Sikorska, who secretly integrated lessons on Polish identity into the school’s curriculum.

In order to escape the strict oversight of Russian officials, Polish-related subjects would be disguised on the class schedules — Polish history was put down as “Botany” while Polish literature was “German studies.” Little Marie, or Manya, was a star pupil who always finished at the top of her class. And she wasn’t just a math and science prodigy, she excelled in literature and languages as well.

Her father encouraged Polish scientists to instill a sense of Polish pride into their students, too, and was later found out by Russian officials. Władysław lost his job, which also meant the loss of the family’s apartment and steady income.

To make ends meet, they got a new apartment — this time a rental — and Władysław started a boys’ boarding school. The flat quickly became overcrowded; at one point, they housed 20 students in addition to Curie’s parents and their five children. Curie slept on a couch in the dining room and would rise early to set the table for breakfast.

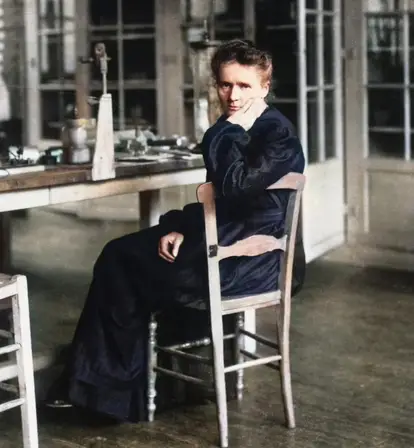

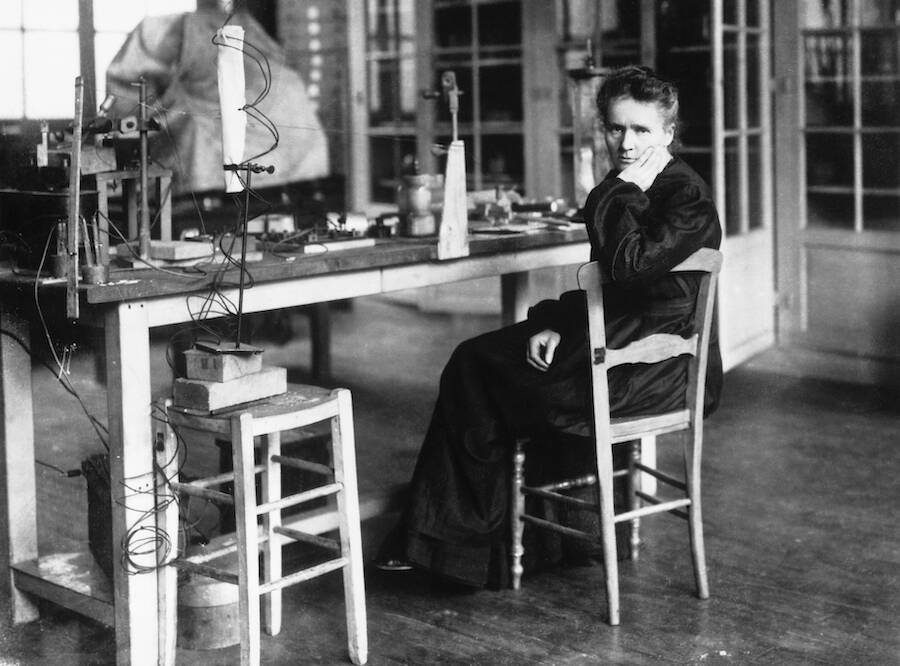

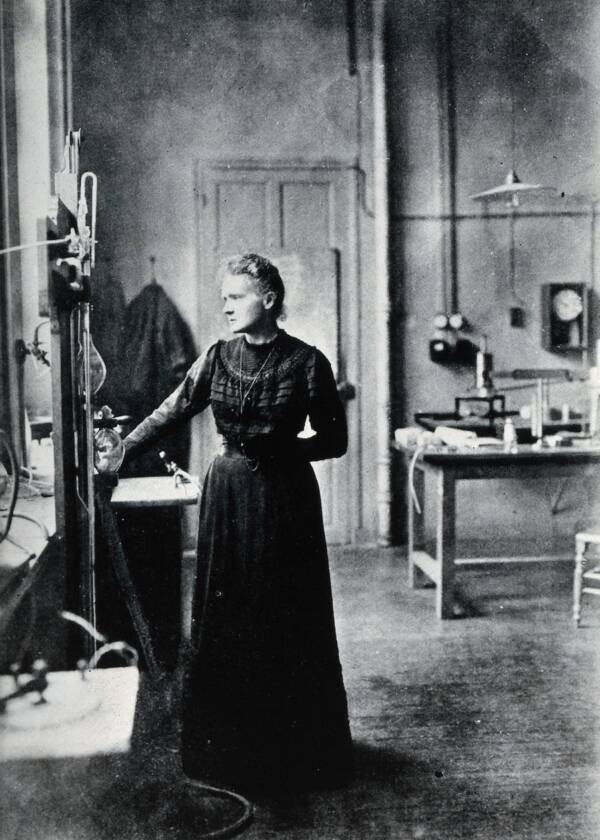

© Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis/Getty ImagesMarie Curie in her laboratory, where she spent most of her adult life.

The overcrowding led to lack of privacy, but also health problems. In 1874, two of Curie’s sisters, Bronya and Zosia, contracted typhus from a few of the sick renters. Typhus spreads via fleas, lice, and rats, and flourishes in crowded places. While Bronya eventually recovered, 12-year-old Zosia did not.

Zosia’s death was followed by another tragedy. Four years later, Curie’s mother contracted tuberculosis. At the time, doctors still had very little understanding of the disease, which caused 25 percent of deaths in Europe between the 1600s and 1800s. In 1878, when Curie was just 10 years old, Bronisława died.

The experience of losing her beloved mother to an illness which science had yet to understand shook Curie’s to her core, plaguing her with lifelong grief and compounding her depression, a condition she would suffer through for the rest of her life. As a way to avoid processing the loss and grief she felt from both her mother’s and sister’s deaths, Curie threw herself into her studies.

She was undoubtedly talented but incredibly fragile from the loss. A school official who was concerned that Curie did not have the emotional capacity to cope had even recommended to her father that she be held back a year until she could recover from the grief.

Her father ignored the warning and instead enrolled her into an even more rigorous institute, the Russian Gymnasium. It was a Russian-operated school that used to be a German academy and had an exceptional curriculum.

Although young Marie Curie excelled academically, mentally she was fatigued. Her new school had better academic standing, but the strict Russia-controlled environment was rough, forcing her to hide her Polish pride. It was not until she suffered a nervous breakdown after graduation at age 15 that her father decided it would be best for his daughter to spend time with family in the countryside.

Marie Curie The Scientist

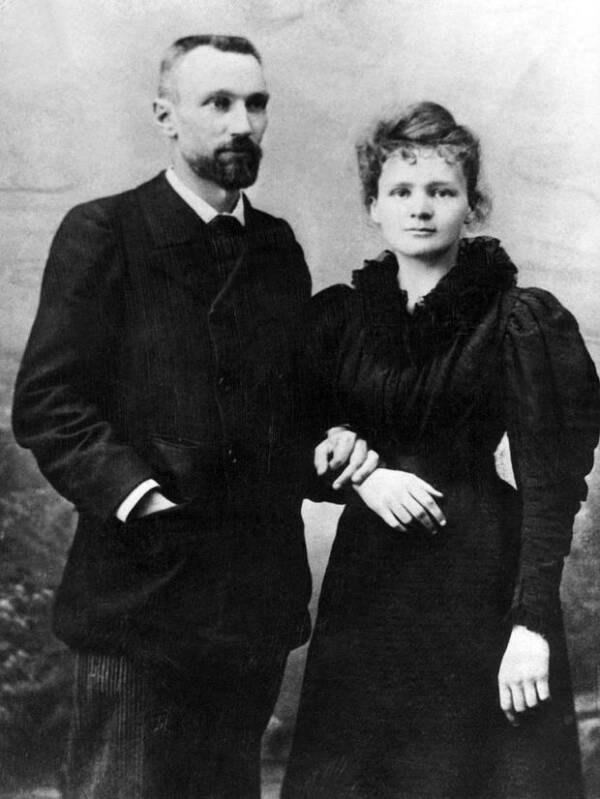

Wikimedia CommonsShe met her husband, Pierre Curie, after they were assigned on the same research project.

It turns out, fresh air and strawberry picking in the quiet countryside was the perfect antidote. The usually studious Marie Curie forgot about her books and enjoyed being lavished with gifts by her mother’s extended family, the Boguskis. She played games with her cousins, took long leisurely walks, and reveled in her uncles’ exciting house parties.

One night, according to the stories she told her daughter, Ève, Curie danced so much that she had to throw her shoes out the next day — “their soles had ceased to exist.”

In a carefree letter to her friend Kazia, she wrote:

“Aside from an hour’s French lesson with a little boy I don’t do a thing, positively not a thing….I read no serious books, only harmless and absurd little novels….Thus, in spite of the diploma conferring on me the dignity and maturity of a person who has finished her studies, I feel incredibly stupid. Sometimes I laugh all by myself, and I contemplate my state of total stupidity with genuine satisfaction.”

Her time spent in the Polish countryside was one of the happiest times of her life. But the fun and games had to come to an end at some point.

Curie Goes To College

When she turned 17, Marie Curie and her sister Bronya both dreamed of going to college. Sadly, the University of Warsaw did not admit women at the time. In order for them to be able to pursue a higher education, they had to go abroad, but their father was too poor to pay for even one, let alone multiple university educations.

So the sisters hatched a plan.

Bronya would depart for medical school in Paris first, which Curie would pay for by serving as a governess in the Polish countryside, where room and board were free. Then, once Bronya’s medical practice found solid footing, Curie would live with her sister and attend university herself.

In November 1891, at age 24, Curie took a train to Paris and signed her name as “Marie” instead of “Manya” when she enrolled at the Sorbonne, to fit in with her new French surroundings.

Getty Images/Wikimedia CommonsMarie Curie, who made significant breakthroughs in physics and chemistry, is regarded as one of the greatest scientists in history.

Unsurprisingly, Marie Curie excelled in her studies and soon launched to the top of her class. She was awarded the Alexandrovitch Scholarship for Polish students studying abroad and earned a degree in physics in 1893 and another in mathematics the following year.

Toward the end of her stint at the Sorbonne, Curie received a research grant to study the magnetic properties and chemical composition of steel. The project paired her with another researcher named Pierre Curie. The two had an instant attraction that was ingrained in their love of science and soon Pierre began courting her to marry him.

“It would…be a beautiful thing,” he wrote to her, “to pass through life together hypnotized in our dreams: your dream for your country; our dream for humanity; our dream for science.”

They were married in the summer 1895 in a civil service attended by family and friends. Despite it being her wedding day, Curie remained her practical self, choosing to don a blue woolen dress that she would be able to wear in the laboratory after her honeymoon, which she and Pierre spent riding bicycles in the French countryside.

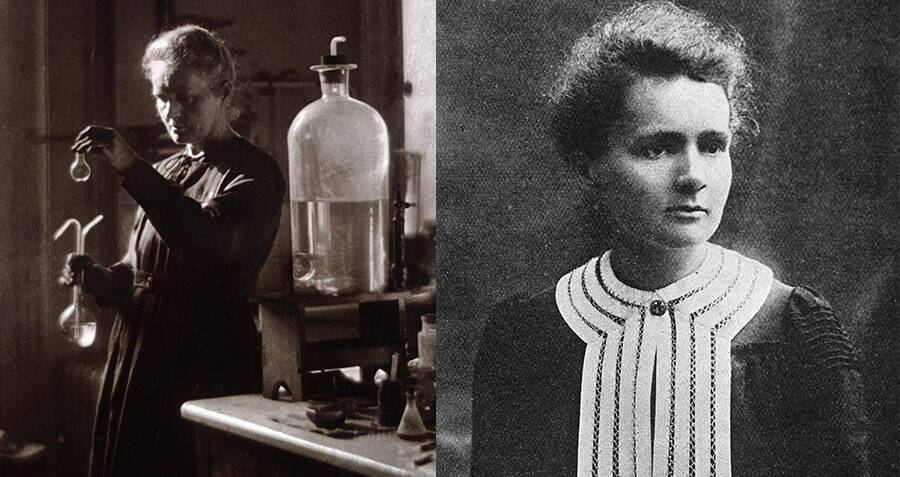

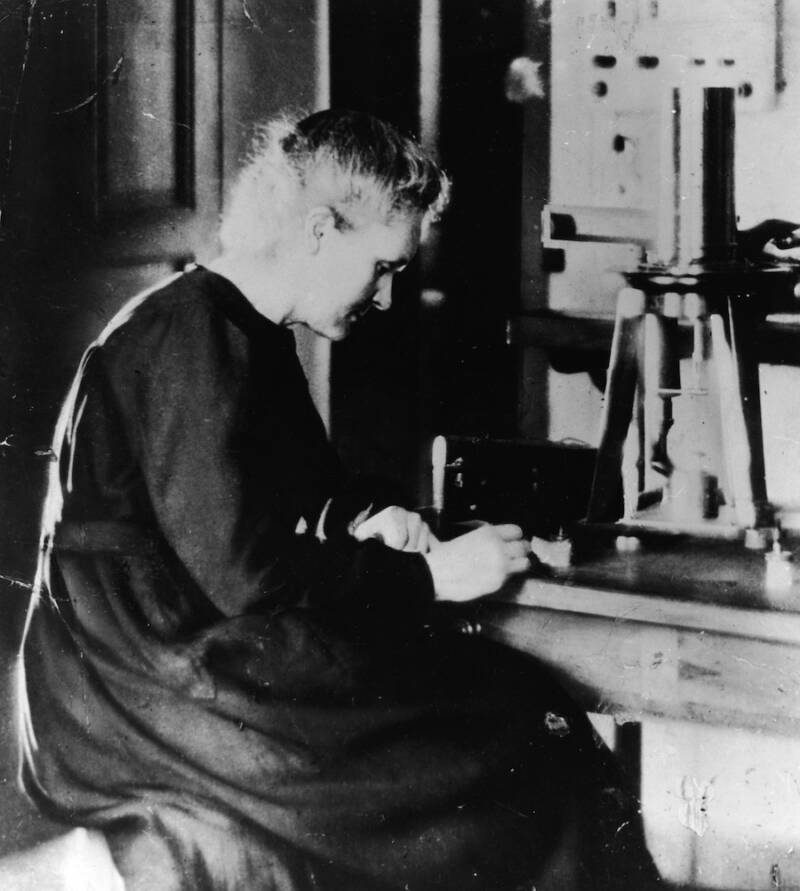

Wellcome CollectionThe brilliant physicist and chemist continued to dedicate herself to research even after she became a wife and mother.

Her union with Pierre would prove beneficial to both her private life and her professional work as a scientist. She was fascinated by German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen’s discovery of x-rays as well as Henri Becquerel’s discovery that uranium emitted radiation, or what he dubbed “Becquerel rays.” He believed that the more uranium — and uranium alone — a substance contained, the more rays it would emit.

Becquerel’s discovery was important, but Curie would build on it and discover something extraordinary.

Her Dedication As A Scientist Was Criticized After She Had Children

Culture Club/Getty ImagesMarie Curie and her daughter Irene, who would later win a Nobel just like her mother.

After her marriage, Marie Curie retained her ambitions as a researcher and continued to spend hours in the laboratory, often working alongside her husband. However, when she became pregnant with their first child, Curie was forced to step back from her work due to a difficult pregnancy. It put a lull in her research preparation for her doctoral thesis, but she endured.

The Curies welcomed their first daughter, Irène, in 1897. When her mother-in-law died weeks after Irène’s birth, her father-in-law, Eugene, stepped in to look after his grandchild while Marie and Pierre continued their work in the lab.

Curie’s unwavering dedication to her work continued even after the birth of their second child, Ève. By this time, she was already used to being chastised by her colleagues — who were mostly men — because they believed she should spend more time taking care of her children instead of continuing her groundbreaking research.

“Don’t you love Irène?” Georges Sagnac, a friend and collaborator, pointedly asked. “It seems to me that I wouldn’t prefer the idea of reading a paper by [Ernest] Rutherford, to getting what my body needs and looking after such an agreeable little girl.”

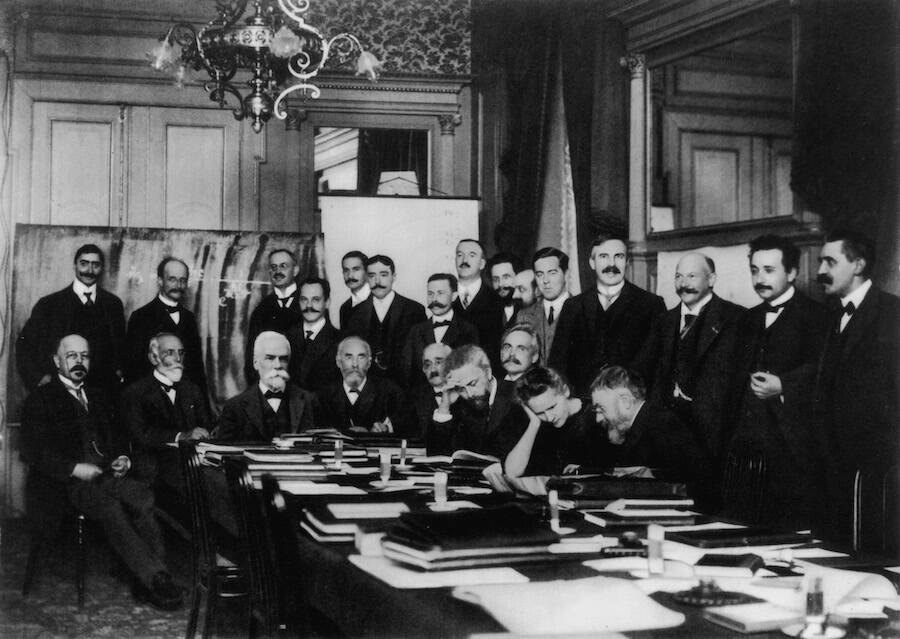

Couprie/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesThe international physics conference in Brussels. Notably, Curie is the only woman in the group.

But being a woman of science at a time where women were not considered to be great thinkers simply because of their biology, Curie had learned to tune it out. She kept her head down and worked closer to what would be the breakthrough of a lifetime.

Marie Curie’s Breakthrough

In April 1898, Curie discovered that Becquerel rays weren’t unique to uranium. After testing how every known element affected the electrical conductivity of the air around it, she found that thorium, too, emitted Becquerel rays.

This discovery was monumental: It meant that this feature of materials — which Curie called “radioactivity” — originated from within an atom. Just a year prior, English physicist J.J. Thomson had discovered that atoms — previously thought to be the smallest particles in existence — contained even smaller particles called electrons. But no one had applied this knowledge or considered the massive power that atoms could hold.

Curie’s discoveries literally changed the field of science.

But Madame Curie — which people often called her — didn’t stop there. Still determined to unearth the hidden elements she had sniffed out, the Curies conducted larger experiments using pitchblende, a mineral containing dozens of different types of materials, to discover heretofore unknown elements.

“There must be, I thought, some unknown substance, very active, in these minerals,” she wrote. “My husband agreed with me and I urged that we search at once for this hypothetical substance, thinking that, with joined efforts, a result would be quickly obtained.”

Curie worked day and night on the experiments, stirring human-sized cauldrons filled with the chemicals she was so desperate to understand. Finally, the Curies got their breakthrough: They discovered that two of the chemical components — one similar to bismuth and the other similar to barium — were radioactive.

In July 1898, the couple named the previously undiscovered radioactive element “polonium” after Curie’s home country of Poland.

That December, the Curies successfully extracted pure “radium,” a second radioactive element they had been able to isolate and named after “radius,” the Latin term for “rays.”

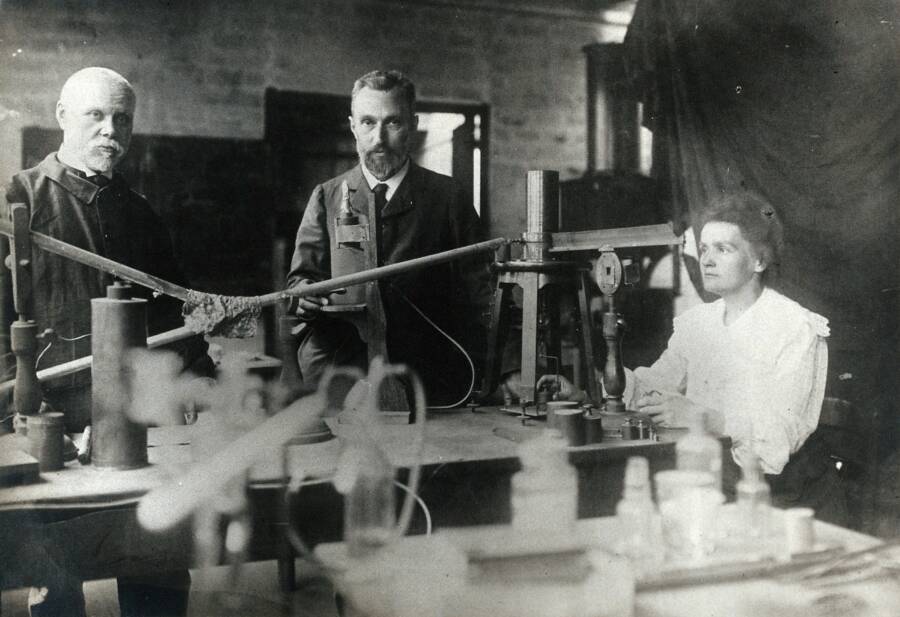

Wellcome CollectionThe Curies, along with fellow scientist Henri Becquerel (left), received the Nobel Prize in Physics for their discovery of radioactivity.

In 1903, 36-year-old Marie and Pierre Curie, along with Henri Becquerel, were awarded the prestigious Nobel Prize in Physics for their contributions to dissecting “radiation phenomena.” The Nobel committee had almost excluded Marie Curie from the list of honorees because she was a woman. They could not wrap their minds around the fact that a woman could be intelligent enough to contribute anything meaningful to science.

Had it not been for Pierre, who fervently defended his wife’s work, Curie would have been denied her deserved Nobel. The myth that she was merely a assistant to Pierre and Becquerel in the breakthrough persisted despite evidence to the contrary, an example of the pervasive misogyny she faced until her death.

“Errors are notoriously hard to kill,” observed Hertha Ayrton, a British physicist and dear friend of Curies, “but an error that ascribes to a man what was actually the work of a woman has more lives than a cat.”

She Was A Great Woman Of Many Firsts

Pictorial Parade/Getty ImagesShe established more than 200 mobile x-rays during the war.

Not only was Madame Curie’s discovery in radioactivity significant for researchers and humankind, it was also a tremendous milestone for women scientists, proving that intellect and hard work had little to do with gender.

After becoming the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, she went on to accomplish more great things. That same year, she became the first woman in France to earn her doctorate. According to the professors who reviewed her doctoral thesis, the paper was a greater contribution to science than any other thesis they’d ever read.

While Pierre received a full professorship from the Sorbonne, Marie got nothing. So he hired her to head the laboratory; for the first time, Curie would be paid to do research.

Unfortunately, her spell of great achievements was tainted by the sudden death of her husband after he was hit by a horse-drawn carriage in 1906. Marie Curie was devastated.

On the Sunday after Pierre’s funeral, Curie escaped to the laboratory, the one place she believed she would find solace. But that did not ease her pain. In her diary, Curie described the emptiness of the room which she had so often shared with her late husband.

“Sunday morning after your death, I went to the laboratory with Jacques….I want to talk to you in the silence of this laboratory, where I did not think I could live without you….I tried to make a measurement for a graph on which each of us had made some points, but…I felt the impossibility of going on…the laboratory had an infinite sadness and seemed a desert.”

In a separate new workbook that she began on that Sunday, Curie’s inability to conduct the experiments properly on her own are detailed in such a matter-of-fact manner without an ounce of emotion, unlike the aching words written down in her diary. Evidently, she tried to hide her deep grief from the rest of the world as hard as she could.

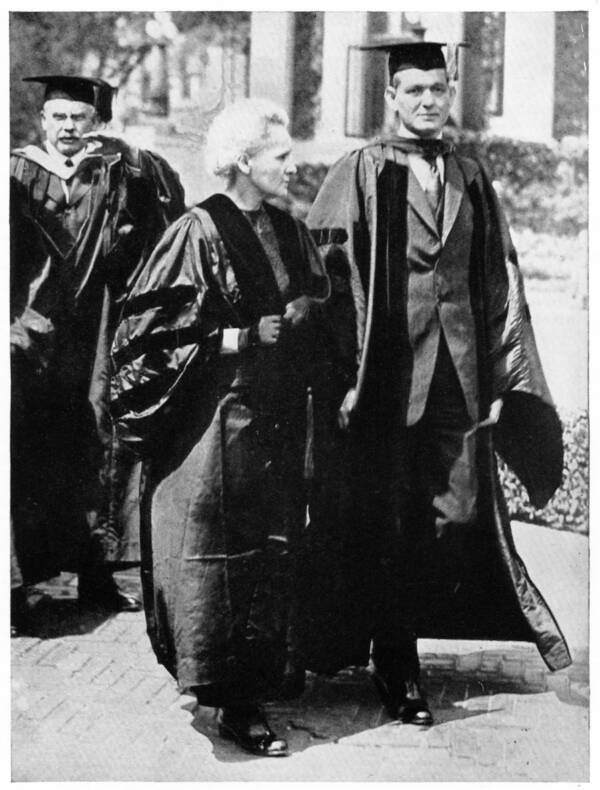

Universal History Archive/Getty ImagesDuring her tour of the United States in 1921 with Dean Pegram of the School of Engineering at Columbia University.

The death of her beloved husband and intellectual partner only added to the devastation that she kept hidden so well since grieving the loss of her mother. As she did before, Curie coped with the loss by throwing herself deeper into her work.

In lieu of accepting a widow’s pension, Marie Curie went on to take Pierre’s place as a professor of general physics at the Sorbonne, making her the first woman to serve in that role. Again, she was almost denied the position because of her gender.

Briefly Plagued With Scandal

Madame Curie faced rampant misogyny even after she had already accomplished what many men could only dream of. In January of 1911, she was denied membership in the French Academy of Sciences, which contained the greatest minds in the country. It was because she was Polish, the Academy believed she was Jewish (which she wasn’t), and as Academy member Emile Hilaire Amagat put it, “women cannot be part of the Institute of France.”

Later that year, Curie was selected to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her research on radium and polonium. But she was almost disinvited from the award ceremony. Mere days before she was to accept her prize in Stockholm, the tabloids published scathing articles about her affair with a younger former student of her husband’s, Paul Langevin.

Wikimedia CommonsPaul Langevin, pictured here in 1897, was married when he and Marie Curie began their love affair.

He was married — very unhappily — with four children, so he and Curie rented a secret apartment together. French newspapers published overly sentimental articles sympathizing with Langevin’s poor wife, who had known about the affair for a long time, and painting Curie as a homewrecker.

Mrs. Langevin scheduled a divorce and custody trial in December 1911, right when Curie was set to travel to Sweden to accept her Nobel. “We must do everything that we can to avoid a scandal and try, in my opinion, to prevent Madame Curie from coming,” said one member of the Nobel committee. “I beg you to stay in France,” another member wrote to Curie.

But Curie didn’t waver, and even Albert Einstein wrote a letter to her expressing outrage at her treatment in the press. She wrote back to the committee: “I believe that there is no connection between my scientific work and the facts of private life. I cannot accept…that the appreciation of the value of scientific work should be influenced by libel and slander concerning private life.”

And so, in 1911, Marie Curie was awarded with another Nobel, making her the only person who has ever won Nobel Prizes in two separate fields.

World War I And Her Waning Years

When World War I broke out in 1914, Marie Curie put her expertise to patriotic use. She established multiple x-ray posts that battlefield doctors could use to treat wounded soldiers and was directly involved in the administration of these machines, often operating and repairing them herself. She established more than 200 more permanent X-ray posts during the war, which became known as “Little Curies”.

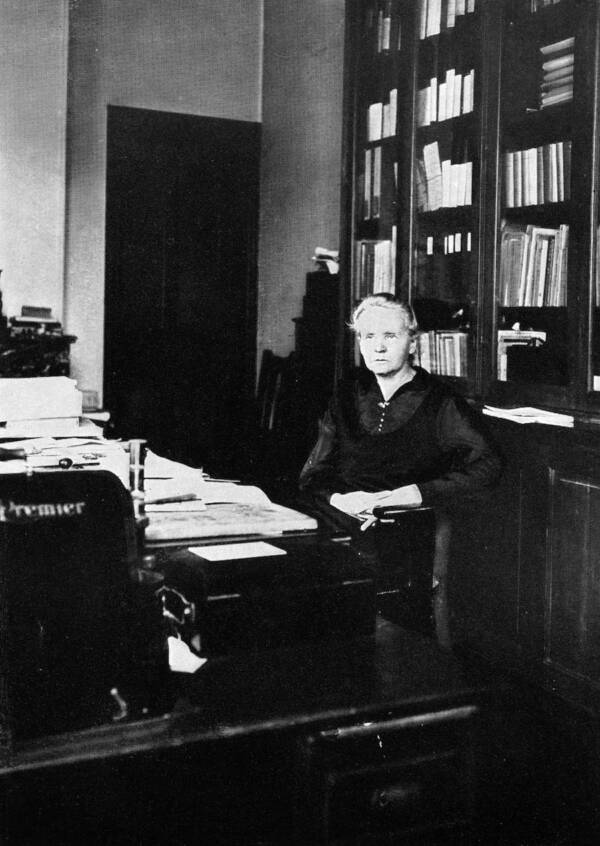

Culture Club/Getty ImagesMarie Curie in her office at the Radium Institute in Paris.

She would go on to collaborate with the Austrian government to create a cutting-edge laboratory where she could conduct all her research, called the Institut du Radium. She went on a six-week U.S. tour with her daughters to raise funds for the new institute, during which she was awarded honorary degrees from such prestigious institutions as Yale and Wellesley universities.

She also earned awards and other distinguished titles from other countries that are too numerous to count; the press described her as the “Jeanne D’Arc of the laboratory.”

Her close work with radioactive elements resulted in significant scientific discoveries for the world, but cost Curie her health. On July 4, 1934, at the age of 66, Marie Curie died of aplastic anemia, a blood disease in which the bone marrow fails to produce new blood cells. According to her doctor, Curie’s bone marrow could not function properly due to long-term exposure to radiation.

Curie was buried next to her husband in Sceaux, on the outskirts of Paris. She accomplished firsts even after her death; in 1995, her ashes were moved and she became the first woman to be interred at the Panthéon, a monument dedicated to the “great men” of France.

Marie Curie’s story is that of tremendous accomplishment, and while many attempted to shape her fate and narrative, focusing on a softer image of her as a wife, mother, and “martyr to science,” the brilliant scientist did it all simply for her love of the field. In her lectures, she proclaimed that her work with radium was that “of pure science…done for itself.”

Now that you’ve learned about the successful brilliance of Marie Curie, meet the world’s first computer programmer, British aristocrat Lady Ada Lovelace. Then, get to know more prolific women in history.