Marie Laveau, the 19th-century "Voodoo Queen" of New Orleans, was a healer and spiritual leader who blended Christianity with Voodoo to support and serve her community.

Marie Laveau, born around 1801 in New Orleans, embodies the city’s complex cultural and racial heritage.

While some contemporaries dismissed her as an evil occultist who practiced black magic and held drunken orgies, New Orleans’ community knew her as a healer and herbalist who preserved African belief systems while melding them with those of the New World.

For decades, she gained respect and prominence in the city for hosting influential community members in her home and offering advice, spiritual guidance tied to both Voodoo and Catholicism, and aid to the sick.

Her compassion and influence extended beyond her lifetime, with her death in 1881 marking the transition of her legacy from a historical figure to a cultural icon.

Today, Laveau is remembered as a symbol of New Orleans’ rich heritage, blending spirituality, resilience, and community service into a lasting legacy that draws thousands of people to the city every year.

Marie Laveau’s Origins Before Becoming The Storied Priestess Of New Orleans

IanDagnall Computing / Alamy Stock PhotoA portrait long believed to depict Marie Catherine Laveau.

Born around 1801, Marie Laveau came from a family who reflected New Orleans’ rich, complicated history. Her mother, Marguerite, was a freed slave whose great-grandmother had been born in West Africa. Her father, Charles Laveaux, was a multiracial businessman who bought and sold real estate and slaves.

According to Laveau’s New York Times obituary, she briefly married Jacques Paris “a carpenter of her own color.” But when Paris mysteriously disappeared, she entered a relationship with a white Louisianan who hailed from France, Captain Christophe Dominique Glapion.

As for whether this type of relationship was common, many historians and locals believe so.

Denise Augustine, a 7th generation Creole storyteller and owner of Our Sacred Stories in New Orleans, told All That’s Interesting that a relationship between a Creole woman of color and a white man would have been very common during Marie Laveau’s lifetime.

“Absolutely it was common. They lived together. He bought property for her. These were respected and honored relationships, and very common,” Augustine explained.

Though Laveau and Glapion lived together for 30 years — and had at least seven children together — they were probably never officially married due to anti-miscegenation laws. In any case, Marie Laveau was known for more in New Orleans than being a wife and mother.

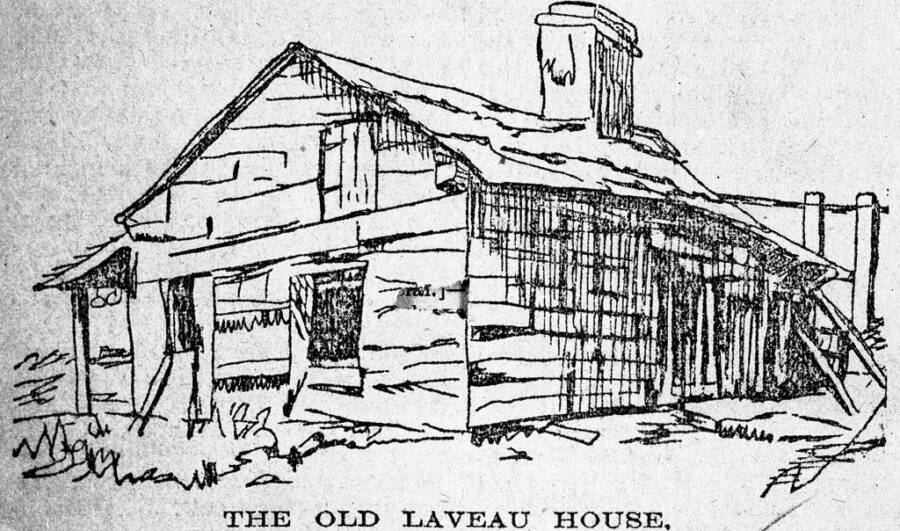

Well-loved and well-respected in the city, Laveau habitually hosted New Orleans’ “lawyers, legislators, planters, and merchants” at her home between Rampart and Burgandy streets. She doled out advice, offered her opinion on current events, helped the sick, and hosted anyone visiting town.

“[Her] narrow room heard as much wit and scandal as any of the historical salons of Paris,” The New York Times wrote in her obituary. “There were businessmen who would not send a ship to sea before consulting her upon the probabilities of the voyage.”

Additionally, Marie Laveau was a practiced Voodoo practitioner who used her skills to help her community.

“There is physical healing in Voodoo. [Practitioners] make teas and gain knowledge about plants. Then there are herbs that you use to make gris-gris bags. There is internal, external, and spiritual healing with herbs in Voodoo. Marie Laveau would have had this knowledge,” Augustine explained.

But Marie Laveau was more than — as The New York Times called her — “one of the most wonderful women who ever lived.” She was called the “Voodoo Queen” of New Orleans and is one of the city’s most famous historical figures.

Spiritual Ceremonies And Community Service In 19th Century New Orleans

Tiago Fernandez / Alamy Stock PhotoOfferings left at the tomb of Marie Laveau in the St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 in New Orleans.

Marie Laveau’s status as a “Voodoo Queen” was no secret in 19th-century New Orleans. Newspapers of her day called her “the head of the Voudou women,” the “Queen of the Voudous,” and the “Priestess of the Voudous.” But what did the Queen of the Voodoos actually do?

Laveau, who likely learned about Voodoo from her family or African neighbors, filled her home with altars, candles, and flowers. She invited people — both black and white — to attend Friday meetings where they prayed, sang, danced, and chanted. As Denise Augustine explained to All That’s Interesting:

“[These ceremonies] would have been passed by word-of-mouth in the community. It could have been passed secretly in the marketplace, or meeting friends down the street. If you had gone for help [previously], she would have let you know when the ceremony was. The ceremony would have been directed at certain things — love, money, luck, ancestors. Women of all races and black and Spanish men — the same people who are the majority of Voodoo practitioners today – would have been there.”

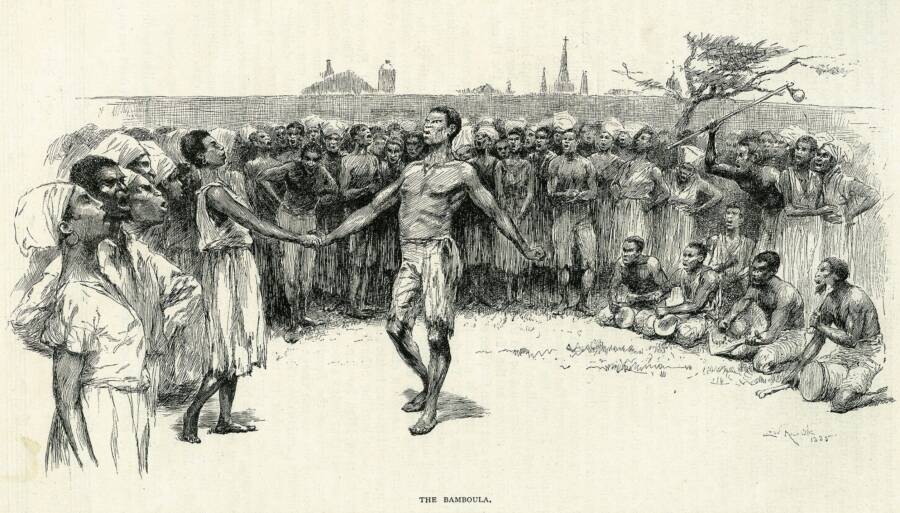

Public DomainAn 1886 illustration of enslaved Africans dancing in Congo Square in New Orleans, where Marie Laveau performed some of her ceremonies.

As Queen, Marie Laveau would have also led more elaborate ceremonies, like on the Eve of St. John the Baptist. Then, along the shores of Lake Pontchartrain, she and others would have lit bonfires, danced, and dove into sacred bodies of water. For this work, Laveau likely received gifts from her ceremony guests.

“Real voodoo practitioners want donations. The donation could have been for the service, and then when the service worked, there would be a continual donation. The slip of 20 or 50 cents into her hand in the marketplace. A beautiful shawl left on her doorstep,” Augustine explained to All That’s Interesting.

But though people of all races visited Laveau and attended her ceremonies, many people never accepted Voodoo as a legitimate religion, especially the Catholic Church. People who witnessed rituals sometimes sensationalized them, and stories spread outside New Orleans that described Voodoo as a dark art.

The Historic New Orleans Collection / The Times-PicayuneAn 1890 illustration of Marie Laveau’s home at 1020 and 1022 St. Ann Street.

Indeed, many people saw it as devil worship, with some black clergy denouncing Voodooism as a backward religion that might impede racial progress in the United States after the Civil War. Even today, as Denise Augustine explained, there is pushback against the religion from both the white and black community:

“Voodoo is looked at today as something evil. Hollywood has done a number on it. Black people are still that mindset that Voodoo is demonology and if you’re not a Christian, you are doing something evil. I cannot fight against that.”

Even The New York Times, which wrote a fairly glowing obituary for Laveau, wrote: “To the superstitious creoles, Marie appeared as a dealer in the black arts and a person to be dreaded and avoided.”

The Historic Legacy Of Marie Laveau

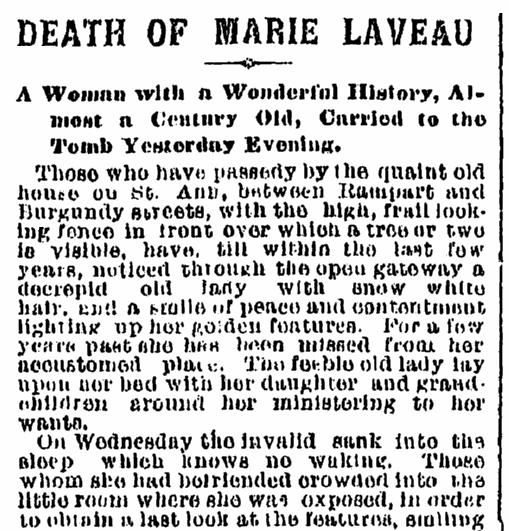

The Times-PicayuneMarie Laveau’s obituary in The Times-Picayune.

In all, Marie Laveau did much more during her life than lead Voodoo ceremonies. She performed notable acts of community service, such as nursing yellow fever patients, posting bail for free women of color, and visiting condemned prisoners to pray with them in their final hours.

“She was compassionate. She buried people — one of the greatest gifts you could give a family is to remove the burden of where they are going to bury their loved ones. She buried children, both white and black, friends, family, and neighbors in her tombs,” Augustine explained.

When she died on June 15, 1881, she was largely celebrated by newspapers in New Orleans and beyond. Some, however, danced around the question of whether or not she had ever practiced Voodoo. Others disparaged her as a sinful woman who’d led “midnight orgies.”

And after her death in 1881, her legend only continued to grow. Was Marie Laveau a Voodoo Queen? A good Samaritan? Or both?

Despite the many mysteries of her life, Marie Laveau has transformed from a historic figure to an almost patron saint figure of New Orleans who represents a cultural and spiritual identity that many people are searching for.

“I think her reputation might be better now. Voodoo is having a resurgence. People are looking into their ancestry — their African spirituality. Marie Laveau would be very popular in this day and age,” Augustine concluded.

Many mysteries remain about Marie Laveau. But what is certain is that her rise wouldn’t have been possible anywhere but in the unique and culturally rich city of New Orleans.

After learning about Marie Laveau, the Voodoo queen of New Orleans, read about Madame LaLaurie, the most fearsome resident of antebellum New Orleans and Queen Nzinga, the West African leader who fought off imperial slave traders.