Mary Seacole faced adversity — and open fire — to help injured soldiers during the Crimean War. Now, more than a century later, she is being remembered for her heroic achievements.

National Portrait Gallery/Wikimedia CommonsMary Seacole, painted by Albert Charles Challen in 1869.

“War, I know, is a serious game, but sometimes very humble actors are of great use in it,” wrote Mary Seacole.

This Jamaican woman was one of these humble actors, saving the lives of many of the thousands of British, French, Turkish, and Russian soldiers sent to fight in the Crimean War in the 1850s. Despite her acts of heroism, however, her name was lost to history for more than a century.

Mary Seacole’s Pre-War Adventures

William Simpson/Wikimedia CommonsMary Seacole, sketched by William Simpson in 1855.

Mary Seacole was born Mary Jane Grant in Kingston, Jamaica in 1805, the daughter of a Scottish soldier and a Jamaican “doctress,” a practitioner of Creole healing arts.

Although slavery in Jamaica wouldn’t be abolished for another three decades, Seacole was technically free. But she and her mother had limited civil rights: While they could own property and slaves of their own, they could not vote, hold public office, or enter many professions.

Seacole grew up learning about medicine from her mother, whose skills were reputable within the community of British officers and soldiers stationed in Kingston. From her father, Seacole acquired a passion for war. From an early age, she was eager to see the battlefield and help fight for the causes she believed in.

By age 12, she was helping her mother heal wounded military officers and others. At 19, she traveled to England for the first time and lived there on and off for the rest of her life. She also visited the Caribbean islands of New Providence, Haiti, and Cuba.

Wikimedia CommonsA photo of Mary Seacole in 1873.

In 1836, she married Edwin Horatio Seacole, but he had a propensity for sickness and died just eight years later. She would never marry again.

After settling back in Kingston, Mary Seacole started practicing medicine, and she soon gained a reputation as a doctress that far exceeded that of her mother. With herbal and natural remedies, Seacole effectively treated diseases like cholera, yellow fever, malaria, and smallpox. In 1850, when cholera swept the island of Jamaica, she treated its victims, “receiving many hints as to its treatment which afterwards I found valuable.”

Indeed she did. The following year, she traveled to the isthmus of Panama to visit her half-brother, Edward, for a short time, building a shop and working as a healer in Cruces.

One evening, her brother dined with a Spanish friend of his. Upon returning home, the Spaniard fell ill and — “after a short period of intense suffering,” Seacole later recounted — he died. The village immediately suspected Edward of poisoning him, but Seacole had a sneaking suspicion.

She inspected the corpse and knew instantly that poison wasn’t the true cause. “The distressed face, sunken eyes, cramped limbs, and discolored shrivelled skin were all symptoms which I had been familiar with very recently,” she wrote, “and at once I pronounced the cause of death to be cholera.”

The community was loath to believe her, but after others began suddenly dying, they had no choice. There were no doctors in town — save one frightened dentist — and so Seacole took the lead in stemming the epidemic. With mustard emetics, warm fomentations, and mustard plasters, she saved her first cholera victim, and then many more. Those who could pay paid her handsomely, and those who couldn’t she treated for free.

After her stint in Cruces, she bounced around to Cuba and then back to Jamaica, just in time for a yellow fever epidemic there. At the same time, though, war broke out in the Balkans. Jamaican soldiers set sail for Europe, and she knew she needed to help them.

Offer To Help, Declined

Wikimedia CommonsInjured British soldiers during the Crimean War.

In 1853, the Crimean War broke out between Russia and the Ottoman Empire.

Fearful of Russian expansion, Britain, and France joined the Ottomans in 1854, sending thousands of soldiers to the Black Sea and the Crimean peninsula. The Kingdom of Sardinia followed suit in 1855.

Within the first year of their involvement, thousands of British soldiers died — most by disease, not combat wounds. After the Battle of Alma, the British government called for a number of female nurses to be sent to the peninsula to lend their services.

At this time, Mary Seacole was living in England and was eager to help. She approached the War Office, asking to be sent to the war zone, but was refused. After a few more failed attempts to travel to Crimea with the British forces, Seacole decided to fund her own trip.

Racism was — of course — the reason. “Doubts and suspicion rose in my heart for the first and last time, thank Heaven,” she wrote. “Was it possible that American prejudices against colour had some root here? Did these ladies shrink from accepting my aid because my blood flowed beneath a somewhat duskier skin than theirs?”

But she decided that societal prejudices wouldn’t stop her from doing what was right. “I made up my mind that if the army wanted nurses, they would be glad of me….If the authorities had allowed me, I would willingly have given them my services as a nurse; but as they declined them, should I not open an hotel for invalids in the Crimea in my own way?”

Mary Seacole’s Heroism In The Crimean War

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty ImagesA battle during the Crimean War. Circa 1855.

Seacole met up with a friend of hers, Thomas Day, in Balaclava, where she began helping doctors transfer sick and wounded soldiers from ambulances to hospitals. She slept on a ship, fighting off thieves, and began to build a shop just outside of the town.

This shop became known as the British Hotel and it was a place that soldiers could go for fresh food and rest. With the hospitals full to the brink, it also became a place for soldiers to seek medical help from the Jamaican doctress.

Mary Seacole, or “Mother Seacole” as many of the soldiers called her, treated the men that came to her hotel as well as the men on the battlefield. The military doctors were familiar with her and allowed her to join them in helping injured soldiers from both sides of the battlefield — often while they were under fire.

In 1855, the Russians withdrew from Sevastopol and began talks of peace. Seacole was one of the last people in Crimea and took part in the local peacemaking. The Treaty of Paris was at last signed on March 30, 1856, and Seacole returned to London.

The Aftermath Of The War

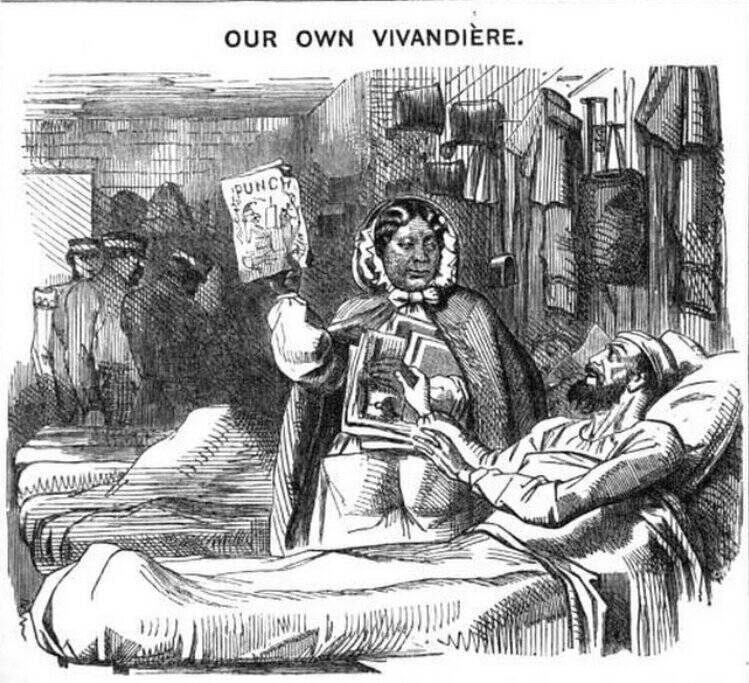

Punch/Wikimedia CommonsA cartoon that mocks Mary Seacole and belittles her heroic acts in the Crimean War.

Back in London, Mary Seacole was struck with poverty. She had spent all of her funds on efforts toward the war, coming back with next to nothing. Although she had to file for bankruptcy, along with Mr. Day, Seacole remained positive and continued to work as a doctress.

“Every step I take in the crowded London streets may bring me in contact with some friend, forgotten by me, perhaps, but who soon reminds me of our old life before Sebastopol; it seems very long ago now, when I was of use to him and he to me,” she wrote, “Now, would all this have happened if I had returned to England a rich woman? Surely not.”

In 1857, Seacole published her autobiography, The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands. It was the first autobiography written by a black woman in Britain, and it quickly became a bestseller.

The newspapers and the British Army started a public campaign to raise money for Seacole, but very little was collected and she remained poor. Additionally, she was ridiculed for her efforts to raise funds and belittled by the British media. The magazine Punch even described as simply a “canteen keeper” during the war.

The doctress often returned to Kingston, where she was loved and honored. Mary Seacole died in 1881 in Paddington, London, and was buried in the Catholic Cemetery at Kensal Green.

Mary Seacole Vs. Florence Nightingale

Wikimedia CommonsFlorence Nightingale, the European nurse that treated hundreds of soldiers during the Crimean War.

In most history books, the shining heroine of the Crimean War is a European woman named Florence Nightingale.

Born in 1820 to a wealthy family, Nightingale pursued nursing as a young woman. During the Crimean War, she was asked by the British Secretary of War to organize a corps of nurses to take along to the war zone to treat the soldiers. There she worked tirelessly, becoming known as “the Lady with the Lamp” because of the way she made her nightly rounds through the dark hallways of the military hospital.

After the war, Nightingale met a hero’s welcome back in England. Queen Victoria awarded her with an engraved brooch and prize of 250,000 pounds, which she used to establish the Nightingale Training School for Nurses at St. Thomas’ Hospital in London. There is also a museum erected in her honor, which stands at the site of the original nurse school.

Wikimedia CommonsMary Seacole, the Jamaican doctress that treated hundreds of soldiers during the Crimean War.

Nightingale’s story is vastly different than Mary Seacole’s, despite the fact that they were championing for the same cause at the same moment in history. In fact, Seacole had even tried to join Nightingale’s corps of nurses, only to be turned away.

While Nightingale is often acknowledged as the pioneer of modern nursing, Seacole had been practicing herbal remedies and hygiene decades before the European woman. And although both women did incredible work during the war, Nightingale’s name lives on, while Seacole’s does not.

This vast difference in their stories is most likely due to the different colors of their skin. As Salman Rushdie said, “See, here is Mary Seacole, who did as much in the Crimea as another magic-lamping lady, but, being dark, could scarce be seen for the flame of Florence’s candle.”

Seacole’s Posthumous Legacy

Wikimedia CommonsThe statue of Mary Seacole outside of St. Thomas’ Hospital in London.

After her death, Mary Seacole was almost forgotten. Her achievements stayed unrecognized in the Western world for over a century — though she was memorialized in Jamaica, where significant buildings were named after her in the 1950s.

Finally, in 2004, Seacole was restored to history when she was voted the top Black Briton for her heroic efforts during the Crimean War. Three years later, she earned her place in history textbooks taught in UK primary schools — alongside Florence Nightingale.

In the 21st century, many buildings and organizations began to commemorate her by name. The Mary Seacole Research Centre was established at De Montfort University, and there are two wards named after her in the Whittington Hospital in North London.

A campaign to erect a statue in Seacole’s honor in London was launched in 2003, and in 2016 it was erected in front of the St. Thomas’ Hospital. Although it faced significant opposition from Nightingale supporters, it still sits there today, engraved with the words, “I trust that England will not forget one who nursed her sick, who sought out her wounded to aid and succour them, and who performed the last offices for some of her illustrious dead.” It is the first public statue of a named black woman in the United Kingdom.

Mary Seacole will be remembered for her heroism, in the face of great adversity and racial prejudice. As she wrote in her autobiography, “Indeed, my experience of the world…leads me to the conclusion that it is by no means the hard bad world which some selfish people would have us believe it.”

Now that you know the story of heroic doctress Mary Seacole, read about 15 other fascinating people that history forgot. Then, read about Gisella Perl, the doctor who saved lives inside Auschwitz.