Before Mary Somerville, the word "scientist" didn't even exist.

Wikimedia Commons

When we think of history’s great scientists, names such as Isaac Newton, Galileo Galilei, or Nicolaus Copernicus likely come to mind. The funny thing is that the term “scientist” wasn’t coined until 1834 — well after these men had died — and it was a woman named Mary Somerville who brought it into being in the first place.

Mary Somerville And The “Scientist’s” Surprising Origins

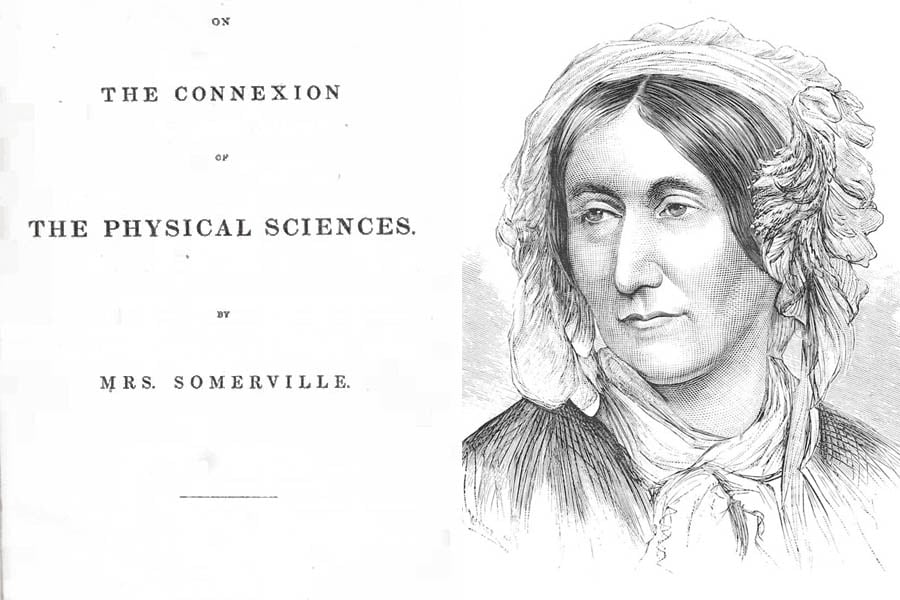

Mary Somerville was an almost entirely self-taught polymath whose areas of study included math, astronomy, and geology – just to name a few. That Somerville had such a constellation of interests, and possessed two X chromosomes, would signal a need to create a new term for someone like her — and scientific historian William Whewell would do precisely that upon reading her treatise, On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences, in 1834.

After reading the 53-year-old Somerville’s work, he wanted to pen a glowing review of it. He encountered a problem, however: The term du jour for such an author would have been “man of science,” and that just didn’t fit Somerville.

In a pinch, the well-known wordsmith coined the term “scientist” for Somerville. Whewell did not intend for this to be a gender-neutral term for “man of science;” rather, he made it in order to reflect the interdisciplinary nature of Somerville’s expertise. She was not just a mathematician, astronomer, or physicist; she possessed the intellectual acumen to weave these concepts together seamlessly.

Mary Somerville’s Early Life

Like so many women of her time, Mary Somerville (née Mary Fairfax) did not have the same educational opportunities as her brothers, despite hailing from a distinguished household. Born in Scotland in 1782, while her brothers attended school Somerville would spend her days wandering by the sea and through the gardens, fascinated by the biological life within.

This of course hampered her early educational development, and when Somerville’s father, Vice-Admiral Sir William George Fairfax, returned from sea he found that his nine-year-old daughter could not read outside of a few Bible verses.

Thus, Fairfax sent his daughter to boarding school for a year, where she learned to read and write (though poorly) and how to perform some simple arithmetic. While she would later condemn the school for beating its students, this turn of events signaled the commencement of Somerville’s nontraditional intellectual journey.

Wikiart/Somerville College, University of Oxford; Supplied by The Public Catalogue FoundationMary Somerville as a young woman, by John Jackson.

When Somerville returned from boarding school — possessing the skills she “needed” as a girl — she continued studying in secret, and would often eavesdrop over her brother’s tutored math lessons. All the while, she accommodated her mother’s wishes by playing the piano, painting, and doing needlepoint — hobbies deemed appropriate for a young girl her age.

It was some of these more feminine hobbies that actually allowed Somerville to further her studies, albeit clandestinely.

At 15, she found algebra equations used as decoration in a fashion magazine. She taught herself how to solve them, and obtained Euclid‘s Elements of Geometry which she read secretly by candlelight. When Somerville had nearly exhausted all the candles in the house, her mother ordered the light source be taken away at bedtime.

Even without a light, Somerville forged on with her studies, which at this point had spread to astronomy and other sciences. Her parents, not knowing what to do with their bookish daughter, married her off to distant cousin Samuel Greig in 1804.

An Unhappy Marriage

Greig also frowned upon Somerville’s desire to learn, thinking that women should not pursue academics. The London-based couple’s marriage was as unpleasant as it was short. When Greig died three years into the marriage, Somerville — at this point a mother of two — could devote more time to her more meaningful relationship with the sciences.

Thus Mary Somerville returned to Scotland, where she was advised by Dr. John Playfair, professor of mathematics at the University of Edinburgh. Wallace proposed that Somerville read French scholar Pierre-Simon Laplace’s Mécanique Céleste (Celestial Mechanics), a recommendation which would change her life.

Wikimedia CommonsMary Somerville, oil on canvas by Thomas Phillips, 1834.

Somerville then grew her library, and eventually encountered a partner who would encourage her academic pursuits, Dr. William Somerville. The couple married in 1812, and when William was elected to the Royal Society, the couple and their four children moved to London — and into the leading scientific circles of the time.

A Storied Success

Living in London in 1827, Somerville would encounter a young lawyer named Henry (Lord) Brougham, who asked Somerville to translate the Mécanique Céleste from its native French into English. Somerville went above and beyond his request, translating it not only to English but also explaining the equations.

At the time, many English mathematicians didn’t understand the equations, and her translation — published in 1831 under the title Mechanism of the Heavens — immediately catapulted Somerville to renown among the scientific community.

Wikimedia Commons/ATI Composite

Ever in the pursuit of self-betterment, it was at this point that a fifty-something Somerville began writing her master work, On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences.

She wrote nine subsequent editions of this treatise, updating it for the rest of her life. These were not purely academic endeavors; they led to material changes. In the third edition, for instance, Somerville wrote that difficulties in calculating Uranus’s position may indicate the existence of an undiscovered planet. This led to the discovery of Neptune.

For the remainder of her life, Somerville racked up a bevy of memberships and titles among the scientific elite.

In 1834, for example, Somerville gained honorary membership into the Society of Physics and Natural History of Geneva and to the Royal Irish Academy. A year later she was voted into the Royal Astronomical Society; by 1870 she had also been inducted into the American Geographical and Statistical Society, the American Philosophical Society, and the Italian Geographical Society.

Mary Somerville continued reading and educating herself until the day she died in 1872, at almost 92 years old. While not a household name, many of her ideas appeared in 20th century textbooks, and her name can be found throughout academic halls and in which she made an impact: Oxford’s Somerville College bears her name, as do one of the Committee Rooms of the Scottish Parliament, a main-belt asteroid (5771 Somerville), and a lunar crater in the eastern part of the Moon.

But perhaps Somerville’s greatest contribution is that which does not physically bear her name, a word meant to describe an individual whose intellectual acuity allows her to convene multiple worlds and disciplines into a single, visionary form: the scientist.

Fascinated by this look at Mary Somerville? Next, read up on equally badass scientists Maria Mitchell and Hypatia. Then, discover six brilliant but overlooked female scientists who should have a larger place in the history books.