Though Maud Lewis spent decades in poverty, rarely leaving her one-room home in Nova Scotia and battling increasingly painful arthritis, she produced some of the most cheerful folk art in Canadian history.

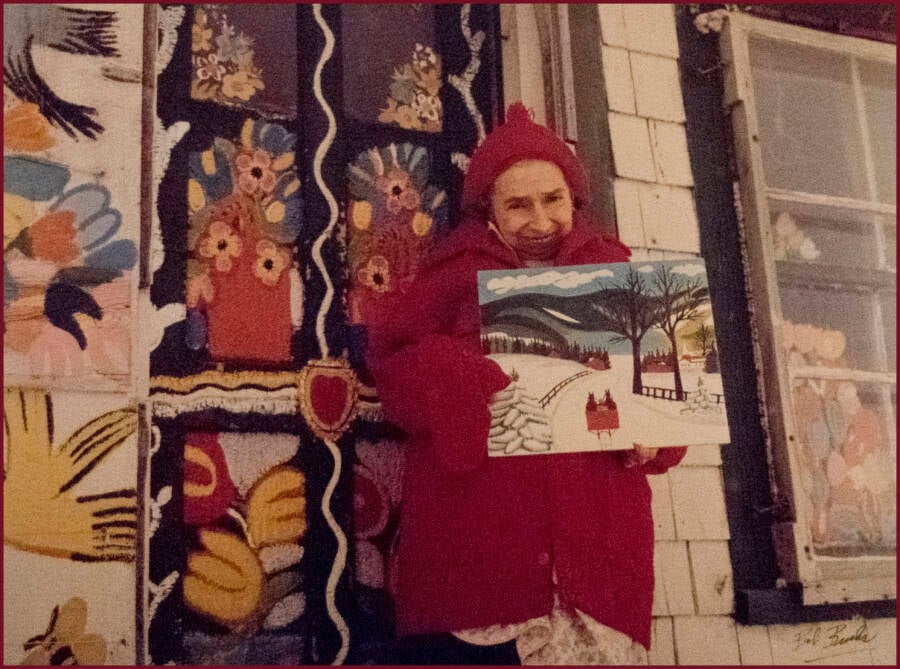

Wikimedia CommonsMaud Lewis, pictured with one of her paintings.

Despite being recognized today as one of Canada’s most renowned folk artists, Maud Lewis spent most of her life impoverished and physically constrained.

Although she was born into a relatively comfortable middle-class family, a lifelong struggle with multiple congenital disorders and increasingly painful arthritis made it difficult for her to be physically active and perform many traditional household tasks. Thanks to her mother’s encouragement, however, Lewis developed a love of painting — a love that would come to define her legacy.

She spent most of her later life in a tiny house in Marshalltown, Nova Scotia, with her husband Everett, a fish peddler. As tending to household chores became increasingly difficult, Maud Lewis would truly begin to paint in earnest. Her brightly colored artworks, sold for just a few dollars apiece, were meant to be a way for her to contribute to the household and support herself and her husband. Instead, Maud Lewis’ paintings became a beloved collection of folk art, a testament to joy and resilience despite poverty and chronic pain.

Maud Lewis’ Early Life And Challenges

Maud Lewis was born Maud Kathleen Dowley in 1901 or 1903 in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia and was raised in the nearby town of South Ohio. The only daughter of John Nelson Dowley and Agnes Mary German, she grew up in a relatively happy, middle-class home alongside her older brother Charles. Her mother also gave birth to two other children, but, tragically, neither lived for more than a few days.

This wasn’t the only difficulty that plagued the family. It was clear early on that Maud had congenital disorders, including a curvature of her spine, acutely sloping shoulders, and a recessed chin. According to the Art Canada Institute, most medical experts today agree that Lewis had likely been born with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, a degenerative condition that often causes extreme pain. That was certainly the case for Maud.

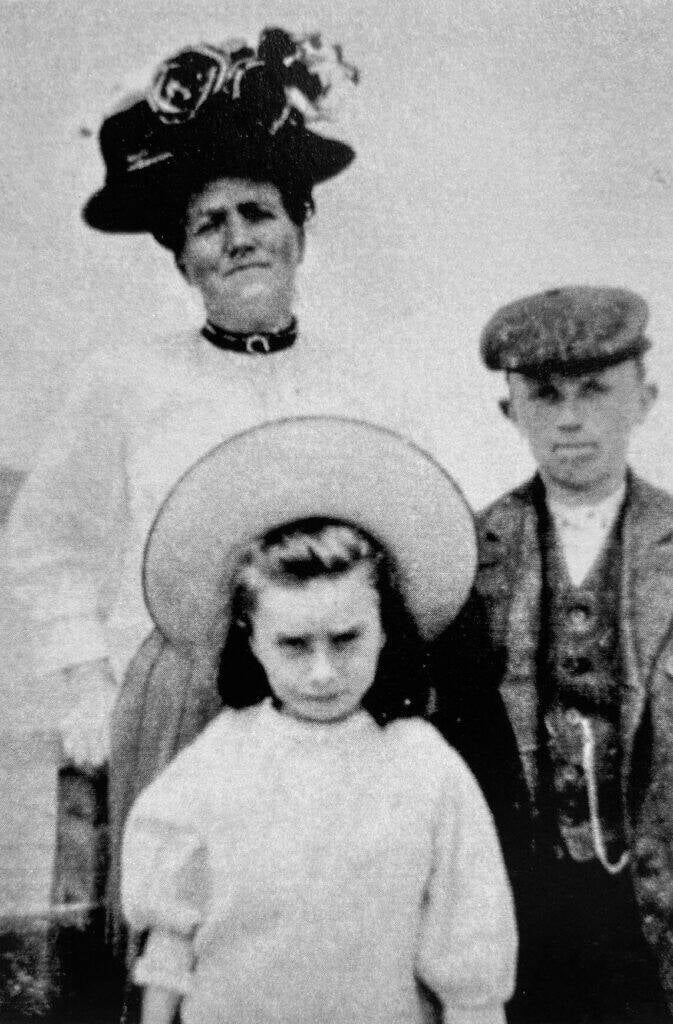

Art Canada InstituteYoung Maud Dowley, pictured with her mother and brother.

Pain was a major limiter. She could not be as physically active as other children, and while she was not a complete recluse, she did spend much more of her time indoors. Living in a rural part of Nova Scotia before automobiles were commonplace was further isolating, even if the Dowley family was financially comfortable.

Still, Maud tried to learn the same skills as other young girls of her time. She learned how to play piano, how to crochet, and how to draw and paint. This last skill was particularly encouraged by her mother, who taught her how to create Christmas cards to sell to neighbors. Likely, this is also when Maud first learned the potential value of her art.

Her father’s influence was just as strong. A skilled craftsman and blacksmith, he had also instilled in her an appreciation for making things with one’s own hands.

Come the mid-1910s, the Dowley family had moved from South Ohio to Yarmouth. While Maud’s father and brother thrived in Yarmouth, however, things only continued to get more difficult for the young girl. Her peers and other children often mocked her for her physical differences and disabilities, and academically, she was falling behind — she did not complete the fifth grade until she was 14 years old. She soon left school entirely.

Art Canada InstituteYoung Maud Lewis with a cat.

“What is life without love or friendship?” Maud had once asked a friend, according to Maud’s official website biography.

She had love at home, where she continued to live with her parents after dropping out of school. It was during this period that Maud began to really focus on her artistic skills, and local stores began selling some of her early Christmas cards and other crafts.

But soon enough, everything would change.

Maud Lewis’ Secret Daughter And Changing Living Situation

A shocking detail often left out of Maud Lewis’ story is the birth of her child. Unmarried at the time, Maud Dowley had become pregnant and given birth to a daughter, Catherine Dowley, in 1928. Lewis’ biographer Lance Woolaver would later identify the child’s father as Emery Allen, who reportedly abandoned Maud after learning she was pregnant.

Maud Lewis never acknowledged or accepted her daughter. She put her up for adoption, and years later, when Catherine tried to track her down and reconnect, Lewis told her, “My child was a boy born dead. I’m not your mother.”

Wikimedia CommonsA series of Maud Lewis’ paintings.

Decades later, in 2019, The Chronicle Herald found Catherine’s daughter, Marsha Benoit, and asked her about the relationship between Catherine and Maud. Marsha found out the truth when she was 12, she said.

“I didn’t know my mother had been adopted until then,” she added. “The people who adopted her were great and I always considered them my grandparents.” She also learned about Catherine’s unsuccessful efforts to reunite with Maud: “It wasn’t something we really talked about. It was pretty well taboo to talk about stuff like that at that time.”

Despite the lack of relationship between Catherine and Maud, Marsha Benoit still looked at her grandmother’s artwork fondly and even said the film based on Maud’s life, Maudie, made her cry both times she watched it.

“I’m glad people remember her,” she said.

Perhaps Maud, while unmarried and in chronic pain, felt she would not have been able to raise a child properly, especially when she was still in the care of her own parents. But her living circumstances would soon change.

Her father died in 1935, and just two years later, so did her mother. Most of their small estate had been left to Maud’s brother as well, and though Maud lived with him and his wife for a brief time, their separation in 1937 soon put an end to that arrangement too. With nowhere else to go, Maud went on to live with her aunt Ida in Digby. It was another short-term arrangement, however, as Maud soon met a fish peddler by the name of Everett Lewis.

Maud And Everett Lewis’ Relationship

The start to their story was anything but romantic. Everett Lewis had placed a series of advertisements around the town, asking for a woman to “live-in or keep house” for his small home in the nearby Marshalltown. Then, one day, he received a knock at his door from Maud Dowley, who had just walked six miles from Digby to inquire about the posting.

Initially, Everett turned her down, walked her about a mile to a railroad underpass, and sent her on her way.

Art Canada InstituteDespite their unusual meeting, Maud and Everett Lewis stayed together until her death.

She tried again a few days later, and somehow managed to convince him not just to let her live in the home, but also become his wife. So, on Jan. 16, 1938, the two got married, and Maud Lewis settled into the one-room house where she would spend the rest of her life.

Her husband was a man accustomed to simple living. His house had no electricity or running water. They bathed in a wash basin or tub, heated the water on the stove, and used an outhouse in the yard as their toilet. It offered far less comforts than the homes that Maud was used to.

Everett had not found the housekeeper he had been looking for, either. His wife’s arthritis had progressed to the point where doing household chores was simply too painful for her. So, Everett did the housework, too. But Maud didn’t just sit idly by — she began painting again.

Maud Lewis’ Rise As An Iconic Painter In Her Final Years

Maud Lewis’ cards had sold fairly well back in Yarmouth, and she figured they would bring in a little extra money to her new home, too. Eventually, she graduated from small cards to full-sized paintings, though she charged just $2 initially, and only ever increased her price to $5.

Her paintings rose in popularity thanks to their bright, distinctive colors and cheerful designs, which often depicted rural landscapes, animals, houses, and boats. They were remarkably joyful for a woman who’d endured so much hardship and was now spending so much of her time in a small house.

As she would later put it, painting itself brought her plenty of happiness: “I’m contented here. I ain’t much for travel anyway. Contented. Right here in this chair. As long as I’ve got a brush in front of me, I’m all right.”

Though Everett and Maud Lewis could have a turbulent relationship at times, Everett was supportive of his wife’s painting. Over the years, his business effectively transitioned from selling fish to selling his wife’s artworks. Their tiny cottage, too, became a canvas for Maud’s painting, attracting visitors who came by, captivated by the bright colors.

But the couple were not experienced promoters, and so much of Maud’s early work was only known to the local community for well over two decades.

That changed in 1964, when Halifax journalist Cora Greenaway interviewed Lewis for the CBC Radio program Trans-Canada Matinee. Suddenly, more people had become interested in Maud Lewis and her paintings, and a 1965 Toronto Star piece about her spread the word even further, describing her as “The Little Old Lady Who Paints Pretty Pictures.”

Wikimedia CommonsMaud Lewis’ restored house at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

When discussing her artistic inspiration with the Telescope, she said, “I put the same things in, I never change. Same colors and same designs. I imagine I’m painting from memory, I don’t copy much. I just have to guess my work up, ’cause I don’t go nowhere, you know. I can’t copy any scenes or nothing. I have to make my own designs up.”

Unfortunately, the increased workload only worsened Lewis’ arthritis, and she found herself increasingly in pain as the 1960s came to a close.

A fall in 1968 led to a broken hip, and from there, Lewis’ health rapidly declined. She traveled back and forth from her house to the hospital, but she never stopped painting up until her death from pneumonia on July 30, 1970. She was either 67 or 69, and some of her last artworks were cards for her nurses.

In 1979, a burglar would break into her now-famous home and kill Everett, apparently convinced that he was hiding some sort of treasure.

Following Everett’s death, the beautifully painted home began to fall into disrepair, prompting a group of concerned citizens to form the Maud Lewis Painted House Society in an effort to save the landmark. They were successful, and in 1984, the house was sold to the Province of Nova Scotia and transferred to the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia for permanent display.

Her story has since inspired documentaries, biographies, and the 2016 film Maudie by director Aisling Walsh. The film, which starred Sally Hawkins and Ethan Hawke, released to generally favorable reviews. But perhaps more importantly, it shared Maud Lewis’ story with an international audience, solidifying her as one of the most renowned folk artists Canada has ever known.

Her granddaughter summarized the appeal of her work best. “I look at the colorful paintings she did when her life was so dark and wonder what she was thinking,” Marsha Benoit said. “I’m sorry I never got to see her.”

After reading the remarkable story of Maud Lewis, go inside the life of Miyamoto Musashi, the Japanese “soldier-artist” who excelled at both swordfighting and painting. Then, discover 52 photos of the enthralling life of Frida Kahlo.