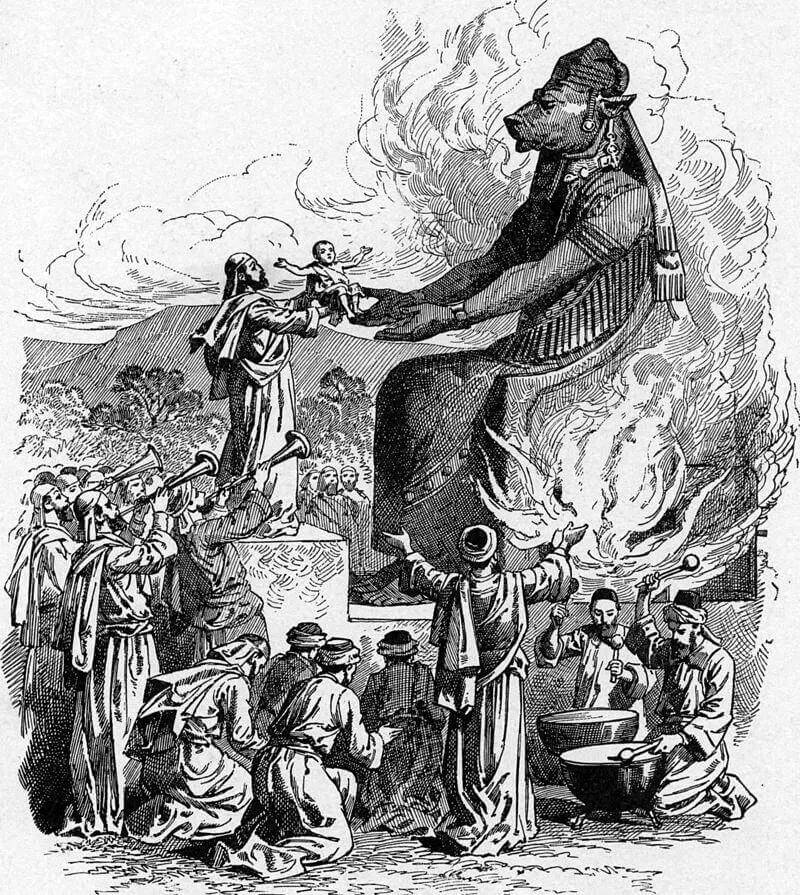

Perhaps no pagan deity was as reviled as Moloch, a god whose cult reportedly sacrificed children in a furnace set inside the belly of a bronze bull.

Throughout antiquity, sacrifice might have been utilized in times of great strife. But one cult stands out from the rest for its brutality: the cult of Moloch, the alleged Canaanite god of child sacrifice.

The cult of Moloch, or Molech, is said to have boiled children alive in the bowels of a big, bronze statue with the body of a man and the head of a bull. Offerings, at least according to some inscriptions in the Hebrew Bible, were to be reaped through either fire or war — and it’s rumored that devotees can still be found to this day.

Who Is Moloch And Who Prayed To Him?

Wikimedia CommonsAn 18th century depiction of the Moloch idol, “The idol Moloch with seven chambers or chapels.” It was believed these statues had seven chambers, one of which was reserved for child sacrifices.

Although historical and archaeological communities still debate Moloch’s identity and influence, he seems to have been a god of the Canaanites, which was a religion born out of a combination of ancient Semitic faiths.

What’s known about Moloch largely comes from Judaic texts outlawing the worship of him and the writings of ancient Greek and Roman authors.

The cult of Moloch is believed to have been practiced by the people of the Levant region from at least the early Bronze Age, and images of his bullish head with a child burning in his belly persist until the medieval times.

His name likely derives from the Hebrew word melech, which usually stands for “king.” There are also references to a Molock in Ancient Greek translations of old Judaic texts as well. These date back to the Second Temple period between 516 B.C. and 70 C.E., before the Second Temple of Jerusalem was destroyed by the Romans.

Wikimedia CommonsStone slabs in the tophet of Salammbó, which was covered by a vault built in the Roman period. This is one of the tophets Carthaginians would sacrifice children in.

Moloch is most frequently referred to in Leviticus. A passage from Leviticus 18:21 condemns child sacrifice, “Do not allow any of your children to be offered to Molech.”

Passages in Kings, Isaiah, and Jeremiah also refer to a tophet, which has been defined as both a location in ancient Jerusalem where there was a special bronze statue internally heated by fire, or the statue itself — into which children were apparently thrown for sacrifice.

Medieval French Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki, otherwise known as Rashi, wrote an extensive commentary on these passages in the 12th century. As he wrote:

“Topheth is Moloch, which was made of brass; and they heated him from his lower parts; and his hands being stretched out, and made hot, they put the child between his hands, and it was burnt; when it vehemently cried out; but the priests beat a drum, that the father might not hear the voice of his son, and his heart might not be moved.”

Comparing Ancient Hebrew And Greek Texts

An illustration from Charles Foster’s 1897, Bible Pictures and What They Teach Us, depicting an offering to Moloch.

Scholars have compared these Biblical references to later Greek and Latin accounts which also spoke of fire-centric child sacrifices in the Carthaginian city of Punic. Plutarch, for instance, wrote of burning children as an offering to Ba’al Hammon, a chief god in Carthage who was responsible for the weather and agriculture.

While scholars still debate whether or not the Carthaginian practice of child sacrifice differed from the cult of Moloch, it’s generally believed that Carthage only sacrificed children when it was absolutely necessary — like during an especially bad draught — whereas the cult of Moloch might have sacrificed more regularly.

Then again, some researchers argue that neither of these cults sacrificed children at all and that “passing through the fire” was a poetic term that most likely referred to initiation rites that may have been painful, but not deadly.

Further complicating matters is that there is every reason to believe these accounts were exaggerated by the Romans to make the Carthaginians appear crueler and more primitive than they were — as they were the bitter enemies of Rome, after all.

Nonetheless, archaeological excavations in the 1920s discovered primary evidence of child sacrifice in the region, and researchers found the term MLK inscribed on numerous artifacts.

Depictions In Modern Culture And Dispelling The ‘Moloch Owl’

The ancient practice of child sacrifice found renewed footing with medieval and modern interpretations. As English poet John Milton wrote in his 1667 masterpiece, Paradise Lost, Moloch is one of Satan’s chief warriors and one of the greatest fallen angels the Devil has on his side.

According to this fictional account, Moloch gives a speech at Hell’s parliament where he advocates for immediate war against God and is then revered on Earth as a pagan god, much to God’s chagrin.

“First MOLOCH, horrid King besmear’d with blood

Of human sacrifice, and parents tears,

Though, for the noyse of Drums and Timbrels loud,

Their children’s cries unheard that passed through fire.”

Gustave Flaubert’s 1862 novel about Carthage, Salammbô also depicted child sacrifice in poetic detail:

“The victims, when scarcely at the edge of the opening, disappeared like a drop of water on a red-hot plate, and white smoke rose amid the great scarlet colour. Nevertheless, the appetite of the god was not appeased. He ever wished for more. In order to furnish him with a larger supply, the victims were piled up on his hands with a big chain above them which kept them in their place.”

This novel is supposedly historical.

Moloch made another appearance in the modern era with Italian director Giovanni Pastrone’s 1914 film Cabiria, which was based on the novel by Flaubert. From Allen Ginsberg’s Howl to Robin Hardy’s 1975 horror classic The Wicker Man — varying depictions of this cult abound today.

Wikimedia CommonsThe statue at the Roman Colosseum was modeled after the one Giovanni Pastrone used in his film Cabiria, which was based on Gustave Flaubert’s Salammbô.

Most recently, an exhibit celebrating ancient Carthage popped up in Rome with a golden statue of Moloch placed outside of the Roman Colosseum in November 2019. It served as a memorial of sorts to the defeated enemy of the Roman Republic, and the version of Moloch used was purportedly based on the one Pastrone used in his film — down to the bronze furnace in its chest, much like the alleged Brazen Bull torture device of ancient Greece.

In the past, Moloch has been connected to Bohemian Grove — a shadowy gentlemen’s club for wealthy elites that met in the San Francisco woods — because the group erected a great wooden owl totem there each summer.

However, this seems to be based on the erroneous conflation between the Moloch bull tophet and the Bohemian Grove owl totem, perpetuated by notorious huckster Alex Jones.

While conspiracy theorists will continue to claim that this is yet another reviled occult symbol of child sacrifice still in use by covert elites — the truth may be less dramatic.

After learning about Moloch, the Canaanite god of child sacrifice, read about human sacrifice in the pre-Columbian Americas. Then, learn about the dark history of Mormonism — from child brides to mass murder.