One of the most famous dyes from the ancient world, Maya blue was used for centuries both because of its vivid color and its durability against the elements — and though researchers first identified this stunning hue at Chichén Itzá in 1931, they had no idea how the Maya made it until recently.

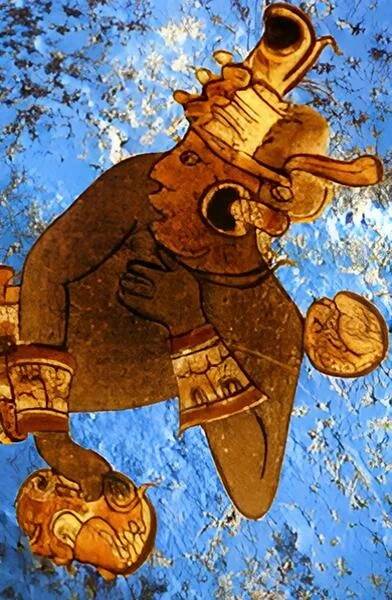

Ricardo David Sánchez, CC BY-SA 3.0A mural in Bonampak, Mexico, with Maya blue used in the background.

Ever since it was first discovered by modern researchers in 1931, scholars have been fascinated with trying to recreate the ancient pigment known as Maya blue.

This vivid hue was used on pottery and murals, and even employed during sacred ceremonies, some involving human sacrifice, across ancient Mesoamerica. But what makes Maya blue truly remarkable is that this color simply does not fade over time. Despite 2,000 years of exposure to the hot and humid climates of southern Mexico and Guatemala, Maya blue has retained its vibrancy.

The method for making such a durable pigment is complex, and for decades its secrets were seemingly lost to time. That changed in 2008, when a team of researchers led by Dean Arnold conducted an analysis of the pigment found on pottery at Chichén Itzá and uncovered a method of recreating Maya blue. The secret, they determined, was a sacred incense called copal, which was heated with indigo and the clay mineral palygorskite over a fire to create this unique pigment.

However, at the annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology in Denver on April 25, 2025, Arnold presented a second method for creating Maya blue. Arnold’s recently published book Maya Blue describes the research process that led to this breakthrough discovery, one that both sheds new light and uncovers new mysteries related to this fascinating pigment.

The Vibrant And Mysterious History Of Maya Blue

Blue and purple pigments historically held great value in ancient cultures. The Egyptians created a blue pigment that adorned many of their temples and eventually spread across Europe as well. In the Mediterranean world, meanwhile, a pigment known as Tyrian purple was worth more than gold.

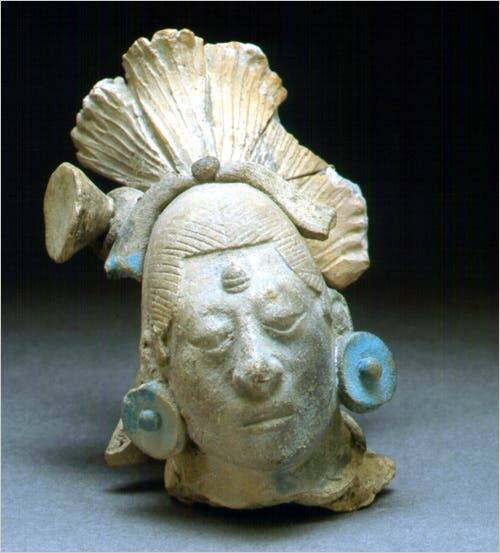

Field MuseumA statue head featuring Maya blue earrings.

But, in some respects, even these pigments pale in comparison to Maya blue.

Although modern researchers only learned of the color in 1931, the ancient Maya used the color extensively. Maya blue was featured prominently on murals and other ancient artifacts, and despite the passage of time it remains as vibrant today as it had been when the Maya first used it, perhaps as early as 600 B.C.E.

The pigment was also associated with the rain god Chaak. Chaak, like many Mesoamerican gods, also happened to be a god of human sacrifice. Rituals to summon the rain involved painting a victim in Maya blue and sacrificing them to Chaak, hoping the god would be appeased and bestow water upon the land.

Public DomainA painting of a Maya warrior, with a Maya blue background.

“We knew blue was a very important color,” Dean Arnold told The New York Times in a 2008 interview. “It was very, very important for the priests and very important for ritual.”

Before Arnold began his own work, scientists first identified some of the components used to make Maya blue back in the 1960s, when chemical analysis of the pigment identified indigo and a clay mineral known as palygorskite as key components. These elements alone weren’t enough to reproduce the color, though, and the mystery of how, where, and when the Maya created this pigment still remained largely shrouded in mystery.

Eventually, Arnold and his team re-examined a Maya bowl that had been sitting at the Field Museum in Chicago for decades, ever since it, numerous other artifacts, and 127 skeletons were uncovered by explorer Edward Thompson in the early 20th century. Thompson had found the artifacts at the bottom of a well in Chichén Itzá, where he also found a 14-foot-layer of blue sediment. Suddenly, with help from these relics, Arnold was able to recreate the color.

How This Fabled Pigment Is Made: Reproducing Maya Blue In The Modern Age

While the exact details of Arnold’s 2008 study are not widely published, his work contributed significantly to understanding how the Maya might have made Maya blue.

Arnold’s initial research focused on the interplay between organic and inorganic materials in the creation of Maya blue. He explored the hypothesis that the Maya used a combination of indigo dye and palygorskite clay, subjected to specific heating processes, to produce the pigment. This approach of Arnold’s aimed to replicate the conditions and materials available to the ancient Maya, and revealed a missing component: copal, a tree resin that was used by the Maya as an incense.

It was a major breakthrough in unlocking the secrets of creating Maya blue, a process that had been sacred to the ancient civilization, known only to priests.

Then, 17 years later, Arnold presented a second method for creating Maya blue, based on evidence that he and his team found in 12 ceramic bowls also excavated at Chichén Itzá. Arnold noticed a white residue inside the bowls that he believed was left by wet-ground clay. The bowls also had small cracks that were seemingly caused by grinding tools.

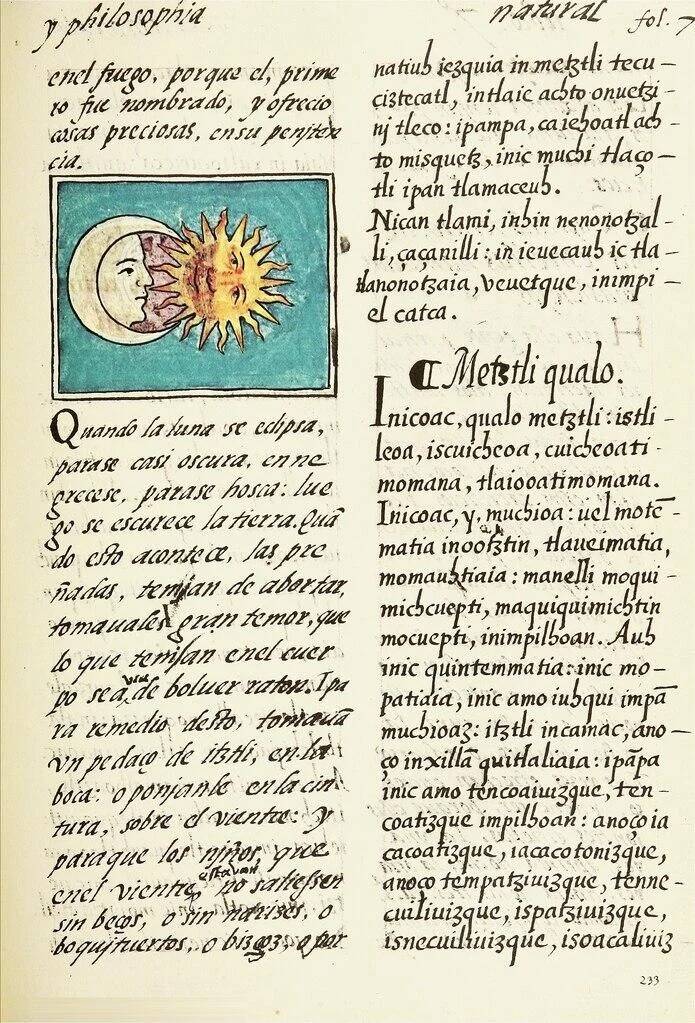

Wikimedia CommonsMaya blue used in the Florentine Codex, a 16th-century study of life in Mesoamerica written by a Spanish friar.

These cracks trapped the clay residue and allowed for microscopic analysis, which revealed charred bits of plant stems, a missing ingredient that went undiscovered until now, as well as signs that the bowl had been heated below. This new evidence suggested that the Maya used local materials, basic tools, and fire to produce Maya blue.

“Consequently, the observations of these bowls provide evidence that the ancient Maya used this method as a second way to create Maya blue,” Arnold said during his 2025 presentation.

That said, the full formula remains elusive. Arnold’s work has helped to solve many of the mysteries surrounding Maya blue, but future research, which Arnold plans to conduct, will help to determine the exact plant species used in the dye.

Even after decades of study, much about the fabled Maya blue continues to remain mysterious.

After reading about the history of Maya blue, learn about the history of El Castillo, the ancient Maya temple that towers over Chichén Itzá. Then, read about Camazotz, the ancient Maya “Death Bat” that serves the lords of the underworld.