"The artifacts are a representation, like a time machine, of... the extreme conditions of life during the First World War."

White War MuseumA lantern left behind by Austrian soldiers in the cave shelter.

For nearly 100 years, a mountain in the Italian Alps kept a piece of World War I literally frozen in time. Ever since Austrian soldiers abandoned their cave hideout on Mount Scorluzzo on Nov. 3, 1918, a glacier has blocked all access to the shelter. Now, as the glacier melts, researchers have discovered a number of thrilling World War I artifacts.

The cave was previously known to historians and archeologists, but it was only in 2017 that the glacier had melted enough to allow entry. The excavation now complete, researchers have found food, dishes, jackets made from animal skins, straw mattresses, and even newspapers and postcards. Such items are an exciting find for World War I buffs — and help shed light on what life was like for soldiers fighting in the mountains.

“The artifacts are a representation, like a time machine, of… the extreme conditions of life during the First World War,” historian Stefano Morosini told CNN.

White War MuseumThe melting of the Stelvio glacier made it possible to enter the cave.

The 20 or so Austrian soldiers who lived in the cave, which sits at an altitude of 10,151 feet, had to survive more than just the fighting itself. Winter temperatures could drop to -40 degrees Fahrenheit. More soldiers likely died from avalanches or hypothermia than actual combat.

“Soldiers had to fight against the extreme environment, fight against the snow or the avalanches, but also fight against the enemy,” Morosini explained.

The soldiers who did survive the dangerous elements engaged in what is known as the White War. This front of World War I was fought between the forces of Italy and the Austro-Hungarian Empire over desolate stretches of Alpine terrain. The Austrians wanted to reach Italy; Italy struggled to push them back.

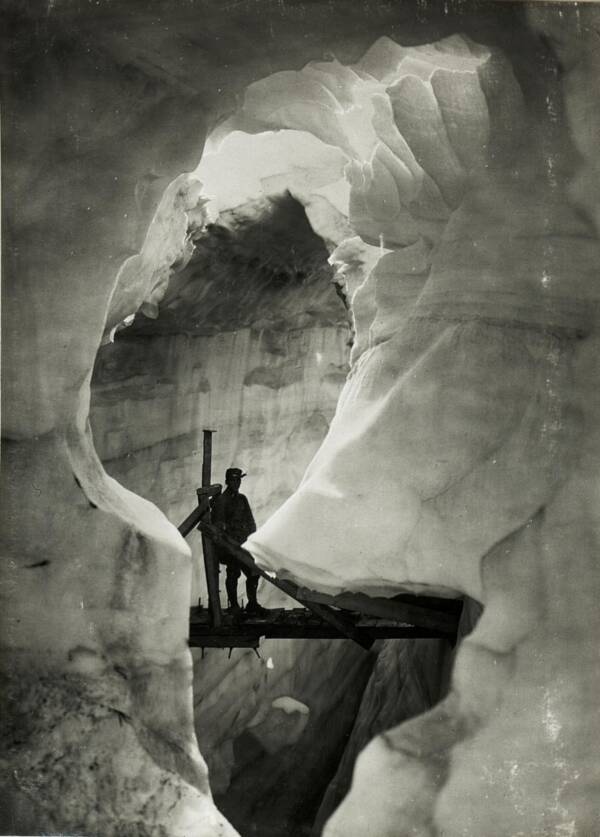

Wikimedia CommonsAn Austrian soldier stands in a tunnel dug within the Marmolada glacier.

New York World correspondent E. Alexander Powell described the violent battles of the White War in poetic terms. “On no front, not on the sun-scorched plains of Mesopotamia, nor in the frozen Mazurian marshes, nor in the blood-soaked mud of Flanders, does the fighting man lead so arduous an existence as up here on the roof of the world,” he wrote in 1917.

After three and a half years of fighting the White War, the Austrian soldiers living in the Mount Scorluzzo cave retreated. World War I was ending — the Italians had come out victorious.

“The findings in the cave on Mount Scorluzzo give us, after over a hundred years, a slice of life at over 3,000 meters above sea level, where the time stopped on November 3, 1918, when the last Austrian soldier closed the door and rushed downhill,” the White War Museum in Adamello stated in a press release.

White War MuseumBottles and tins recovered from the cave.

At the end of the war, the glacier moved in and locked the cave’s artifacts into place. And across the mountain range, glaciers also preserved corpses of soldiers who’d died in the conflict.

“A corpse is found every two or three years, usually in places where there was fighting on the glacier,” said Marco Ghizzoni, who helped to excavate the Mount Scorluzzo cave and works at the White War Museum.

In 2020, hikers came across the frozen corpse of a World War I soldier wrapped in an Italian flag. A few years earlier, two World War I soldiers were found with documents that allowed their families to identify and bury them.

Office for Archeological Finds, Autonomous Province of Trento

The corpse of an Italian soldier, previously frozen in a glacier.

Morosini credits the discovery of the corpses and the cave relics to one thing — a warming planet.

“The knowledge we’re able to gather today from the relics is a positive consequence of the negative fact of climate change,” he said.

The effect of climate change is stark in the Italian Alps. One of Italy’s largest glaciers, called Forni, has retreated 1.2 miles in the last century and nearly half a mile just in the past 30 years. Although the shrinking glaciers can reveal bits of history, they also can trigger landslides and hurt wildlife. In 1987, large portions of the Forni glacier collapsed, causing the Val Pola landslide that killed 43.

But the shrinking Stelvio glacier, at least, has shed light on the lives of the Austrian troops who lived on the mountain. “It’s a sort of open air museum,” Morosini said.

The collected artifacts will be preserved at a new museum dedicated to World War I in the Italian town of Bormio set to open in 2022.

After learning about the World War I cave revealed by a receding glacier, read about how melting ice in Norway has unearthed over 1,000 Viking artifacts. Or, see how a melting glacier in Switzerland revealed the bodies of a couple that went missing in the 1940s.