William Henry Hance

Wikimedia Commons (l.) / Netflix (r.)William Henry Hance (l.) after his arrest in Georgia in 1978, and Corey Allen (r.) portraying Hance in the Netflix show Mindhunter.

In 1978, Georgia was in the middle two separate serial killing sprees that intersected one another along the explosive racial fault lines of the time.

One killing spree, that of the Stocking Strangler, who targeted elderly white women in Georgia, was believed to be a black man and Georgia law enforcement had made that part of their profile of the suspect public.

The second killing spree belonged to William Henry Hance, a U.S. Army specialist stationed at Fort Benning on the Georigia-Alabama border.

Local police received a letter on Army stationery claiming to be from the “Forces Of Evil,” a posse of seven white men who were holding a black woman hostage and that she would be killed if the Stocking Strangler wasn’t apprehended.

The letter gave instructions that police were to contact them using messages broadcast over TV and radio broadcasts.

Given the climate of racist animous in Georgia in 1978 as well as its history of lynchings and other crimes committed by white supremacists against the black population of the state, the letter wasn’t something that on its face could be discounted.

But the supposed hostage, Gail Jackson, was already dead. Her body was found in April of that year and soon police received A phone call directing them to the body of Irene Thirkield, another black woman, which was found at the Fort Benning rifle range.

It had the appearance of a racial tit-for-tat between a black serial killer and the kind of white supremacist vigilante response to his remaining at large.

Robert Ressler, however, wasn’t fooled. After the second body was found, he prepared a behavior profile of the killer that described him as a black man, most likely a low ranking soldier at Fort Benning, in his late twenties.

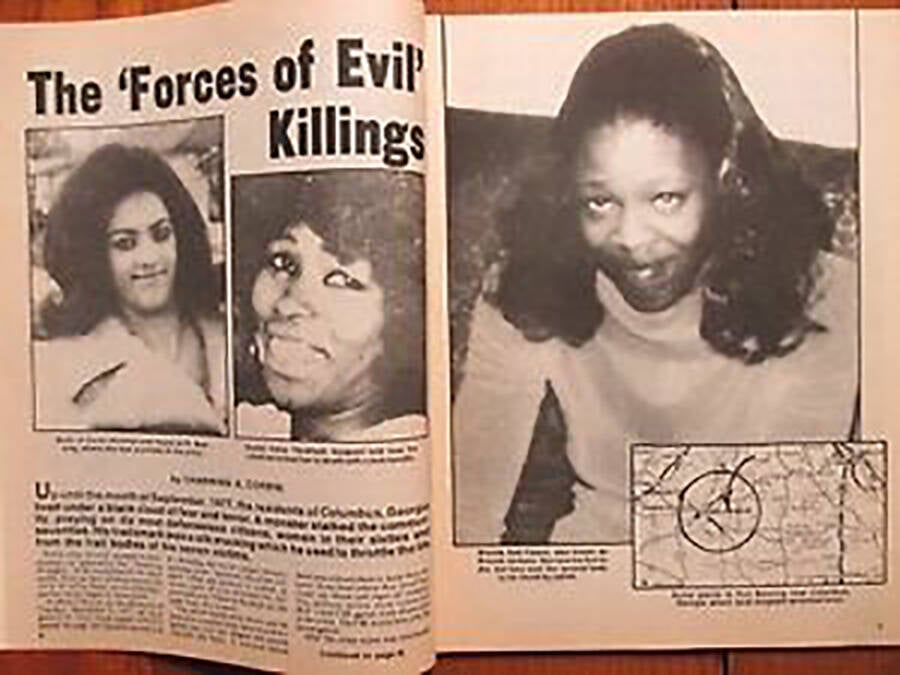

Startling DetectiveWilliam Henry Hance was identified as the killer in the murders of four women in the late 1970s.

Local investigators knew that Jackson and Thirkield had been sex workers, so based on the profile of the killer, they believed that the killer would have met the women at a local bar with predominantly black customers.

That is where investigators found William Henry Hance, a U.S. Army Specialist working as an artillery unit truck driver. Voice and handwriting samples matched the letters sent by the “Forces Of Evil” as well as phone recordings made to police.

Hance confessed to the killings of the two women as well as a third woman, a white woman named Karen Hickman, who was a Private at Fort Benning who was murdered in 1977. He was also identified as the killer in another murder of a young black woman, this one up in Indiana, at Fort Benjamin Harrison.

Hance had no other connection to the Stocking Strangler killings other than to use them as a part of his disinformation effort against investigators.

Convicted in both civilian and military courts, it was his civilian prosecution for murder that ended with Hance being sentenced to death, a controversial one at that.

As his story in Mindhunter shows, Hance had questionable mental capacity, scoring a 71 on an IQ test, which would put him near the threshold for mental incapacity. A second test scored him in the nineties, which is considered normal.

He was executed anyway, but the only black person on the jury that sentenced him to death later came forward and revealed the blatant racism of the jurors who voted for execution, and who did so largely because Hance was a black man.

When the black juror voted against the death sentence due to the question of Hance’s mental competency — Georgia required a unanimous vote to impose the death penalty — the other jurors told her that she swore under oath during jury selection that she “could” impose the death penalty in the case. The jurors told her that if she held out or voted against the death penalty, she could be charged with perjury.

The jury foreman notified the judge that they had reached a unanimous verdict and the jury filed into the courtroom.

A New York Times report from 1994 explains how William Henry Nance was sentenced to death.

“‘I was scared to death,’ Ms. Daniels said.

“Afraid that she could be charged with perjury for having said that she could vote for a death sentence, and afraid that she would get in trouble for not participating in the jury’s final votes, Ms. Daniels said yes — ‘just like all the others’ — when the jurors were polled on their verdict.”