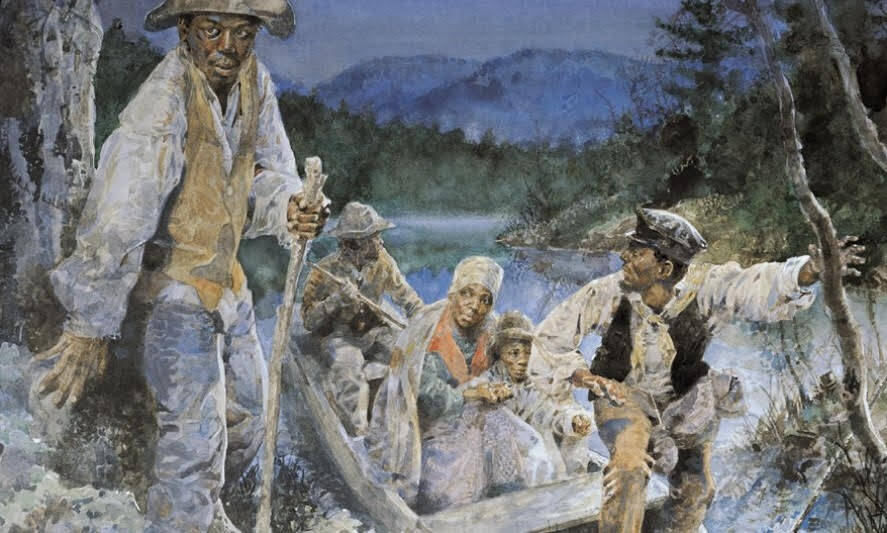

Even though 77 hopeful fugitives were caught just two days after trying to escape aboard The Pearl, their daring attempt would inspire abolitionists nationwide.

National Parks ServiceThe Pearl Incident was the largest escape attempt made by American slaves in the nation’s history.

In 1848, Washington D.C. was a bustling hub of leadership and trade, but it was also a major slave-trading center.

The city had dozens of slave pens and markets dedicated to the horrific sale of human beings. But that year, one man’s desperation culminated in the largest, and potentially most brazen, attempted slave escape the nation had ever seen. One night, 77 slaves covertly boarded the schooner The Pearl with the help of a small group of abolitionists.

Even though the slaves were all captured and sold into the Deep South as punishment just two days later, their plight inspired the writing of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and even sparked the illegalization of the slave trade in the nation’s capital — an important first step on the road to emancipation.

The Pearl Incident or Pearl Affair, as it’s come to be known, also inspired abolitionist sentiment across the nation. But before it became a symbol for the end of slavery, the story of the Pearl Incident began with one earnest man named Daniel Bell.

Daniel Bell Devises An Escape Plan

Library of Congress“Slave pens” like this one were once scattered throughout Washington to hold slaves before they were sold.

It was America in 1848 and chained slaves were marched regularly before the White House and Capitol Hill on their way to slave markets in Virginia and Maryland, and to the dreaded plantations of the Deep South.

Life was a sickening tangle of freedom and bondage for African Americans in early 19th-century Washington, D.C. Families included both enslaved members and those who had been freed. Many slaves found it easier to buy their freedom with wages earned from side jobs and piece work, often laboring years to save enough to purchase the freedom of their children.

One such man was Daniel Bell, a blacksmith at the Washington Navy Yard whose wife and children remained enslaved after he had secured his freedom.

Bell, his wife Mary, and their six children were once owned by a man named Robert Armistead. At one point, Mary was freed and the terms of enslavement for six of their children were reduced.

But when Armistead’s widow filed an inventory of her estate and listed the Bells’ children as slaves, Daniel and Mary struggled for years to free their children through the courts.

When they lost the case, the Bells knew they had to act quickly to secure their freedom and avoid being torn apart.

Bell consequently contacted Daniel Drayton, an abolitionist ship captain based in Philadelphia, through the Underground Railroad. Drayton agreed to charter a schooner and smuggle as many slaves as possible to the free northern states, but sailing the 225 miles successfully would require reliable wind and an inconspicuous vessel that could avoid unsympathetic sailors.

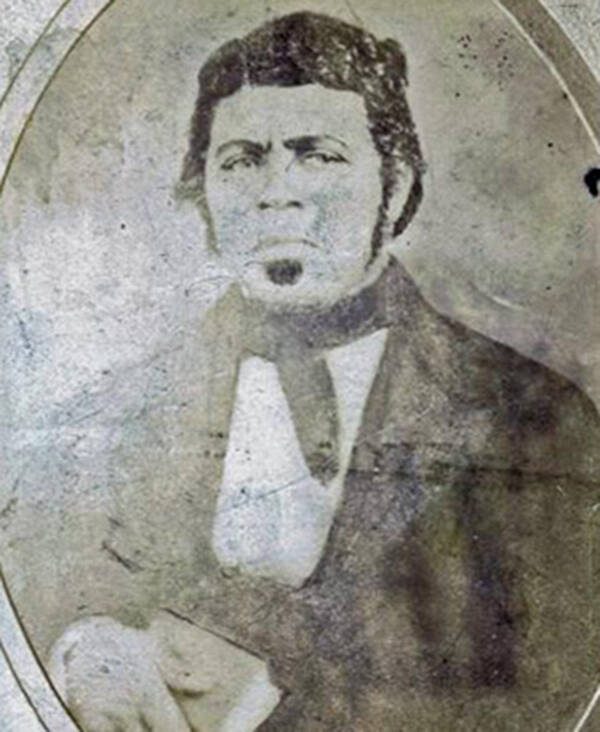

Bell was also aided in his escape planning by a former slave of James Madison named Paul Jennings whose memoir, A Colored Man’s Reminiscences of James Madison, was historically instrumental in revealing the private life of one of America’s early presidents.

Meanwhile, Drayton chartered The Pearl from fellow captain Edward Sayres for $100 and planned for the ship to transport 77 fugitives northward on the night of April 15, 1848.

The Pearl Incident

National Parks ServicePaul Jennings was once in the service of James Madison.

That night, 63 adults and 14 children crept out of their quarters following the 10 p.m. curfew that had been set for black residents in D.C. Then, they boarded the ship.

Among them was Mary Bell and eight of her children, two of her grandchildren, as well as the enslaved sisters Mary and Emily Edmonson with four of their adult siblings. All told, the voyage included dozens of people of all ages who longed to be free.

Weighing anchor under fog and rain, and with a steady wind behind, all was looking well for the daring fugitives. But their luck would soon turn in more ways than one.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Pearl, a small schooner like this one, was the vessel that almost carried 77 enslaved people to freedom one fateful night in 1848.

The strong wind and fog soon dropped off, leaving The Pearl and its cargo creeping along in full sight of any sharp-eyed lookouts. At the time, there were hefty rewards for reported runaways and legal penalties for those who failed to tell on them. Tensions were high on board.

Captains Drayton and Sayres had only the help of a cook named Chester English on board. Between the three of them, they would have to find a way to sail the ship more than 100 miles down to the Potomac River and into the Chesapeake Bay. Once there, they would have to sail north for 120 miles to reach safety, preferably all under the cover of darkness.

But more worrisome than the weather was treachery. Back onshore in Washington, a black wagon driver named Judson Diggs, “a man who in all reason might have been expected to sympathize with their effort,” reported the fugitives.

Diggs had driven one of the escapees to the docks but when his penniless passenger promised to send payment south and fled, Diggs decided he would give them all up.

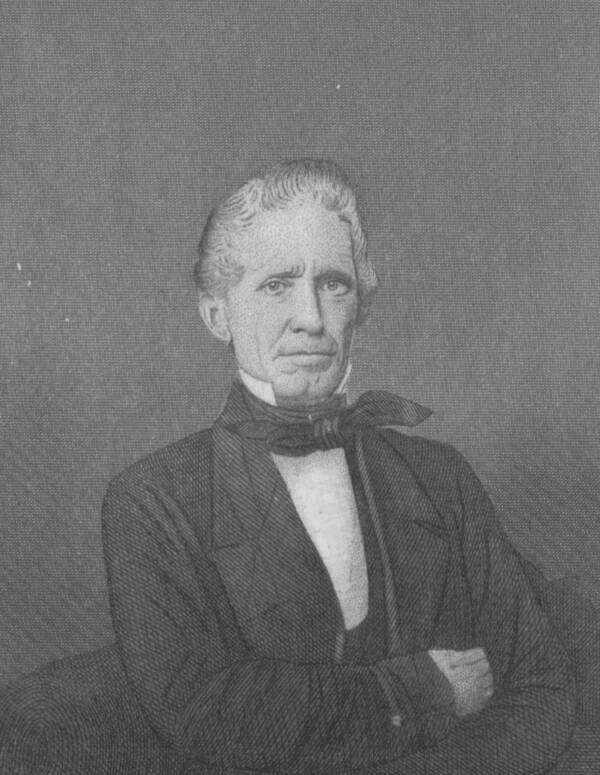

Library of Congress Captain Daniel Drayton was once apathetic toward slavery, but then he converted to Christianity and became a dedicated abolitionist.

By the next morning, a slaveholder named Dodge noticed several of his slaves missing and immediately gathered a gang aboard his steamship, Salem, to hunt them down.

With the advantage of technology, the posse soon overtook the fugitives in Cornfield Harbor, where they had dropped anchor to wait for the wind to return.

Riots In The Capital

The men of Salem immediately boarded the little schooner, but the men, women, and children aboard The Pearl wouldn’t give up so easily.

At first, they fought their attackers, but Captain Drayton recognized the futility of that effort and, hoping to save the lives of his passengers, convinced them to lay down their arms. The 77 passengers were clapped in irons and the ship was towed back to Washington.

When they steamed into the harbor, Sayres, Drayton, and English, along with many of the male slaves, were displayed on deck like trophies to the thundering applause of spectators on the docks.

Sayres and Drayton were charged with 36 counts of larceny and 77 counts of illegally aiding the escape of slaves. Unable to pay the $10,000 in fines, equivalent to more than $327,000 today, they were both sentenced to prison.

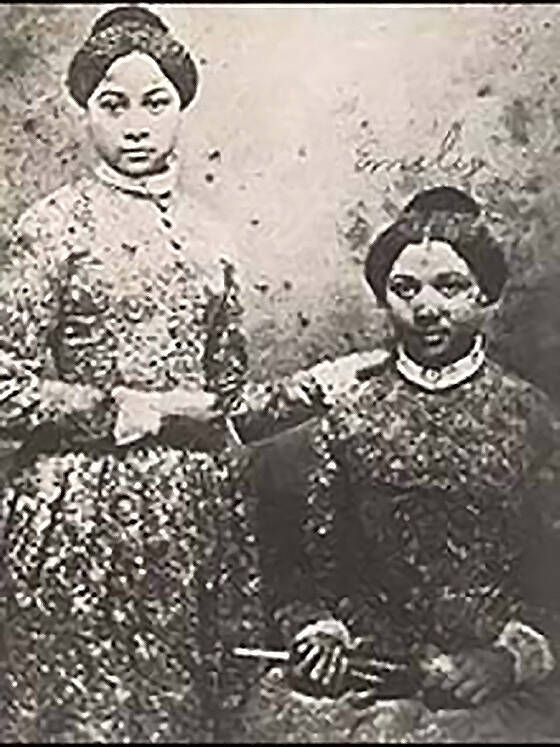

Wikimedia CommonsThe Edmonson sisters, Mary (standing) and Emily, shortly after they were freed in 1848.

For the passengers of The Pearl, a darker fate was in store. As punishment for daring to attempt to free themselves, the slaves’ masters sold them all to new owners in the Deep South, which was known for its hostility. For days after their recapture, pro-slavery mobs rioted in D.C., targeting anyone with even suspected abolitionist sympathies.

The Role Of The Pearl Incident In Abolition

The father of the two sisters Mary and Emily on board the The Pearl, Paul Edmonson, traveled alone to New York to approach the Anti-Slavery Society for help in freeing his daughters. Through them, Edmonson found the help of the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher.

Beecher held a meeting on behalf of the sisters and raised more than $2,200 in less than 30 minutes to purchase their freedom.

Edmonson’s daughters were among the few victims of the Pearl Incident who were freed and they also received an education paid for them by abolitionists. These women would spend the next 12 years writing and speaking against slavery and advocating for its complete destruction.

Library of CongressHenry Ward Beecher, the abolitionist and father of Harriet Beecher Stowe, helped to raise funds to purchase the freedom of many of the Pearl captives.

Although the end of widespread slavery wouldn’t come for some years, in Washington, D.C., at least, it was living on borrowed time.

In the wake of the Pearl Incident, the sale of human beings was banned by Congress in the Compromise of 1850, forcing the merchants of human misery to move into neighboring states that allowed the sale or to work underground.

Finally, in 1862, as the war against slavery raged, Abraham Lincoln freed every slave in the capital, ending a dark and shameful chapter in that city’s history.

After reading about the Pearl Incident, learn about another daring escape made by Robert Smalls, who defied the Confederacy to reach freedom. Then, learn the little-known story of William Still, a man who helped hundreds of slaves escape to the North.