Philip Zimbardo conducted the Stanford Prison Experiment to study the dynamics between inmates and prison guards — but it went infamously wrong after just six days.

TEDx Talks / YouTubePhilip Zimbardo giving a TED Talk in 2012.

Most people know the story of the Stanford Prison Experiment. In 1971, a group of student volunteers agreed to act as guards or prisoners for two weeks. The ensuing cruelty of the guards was so shocking that the experiment was canceled after just six days. But though the experiment is well-known today, the story of the man behind it, Philip Zimbardo, is not.

A trained psychologist who taught at Yale, New York University, Columbia, and Stanford, Zimbardo was interested in studying human behavior. In 1971, he set up the Stanford Prison Experiment to explore the dynamics that emerged between prisoners and prison guards. But things quickly went awry.

The guards became power-hungry and cruel; the prisoners, weak and submissive. Zimbardo’s experiment was called off, but has since become one of the most famous psychological studies of the 20th century.

This is the story of Philip Zimbardo, from his formative childhood, to the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment, to how he’s defended the controversial study against critics in recent years.

How Philip Zimbardo’s Upbringing Inspired Him To Pursue Psychology

Born in 1933, Philip Zimbardo grew up in a poor part of the Bronx in New York City. As he told Psychology Today in a 2000 interview, he had a formative experience at the age of five when he contracted double pneumonia and whooping cough and was sent to the Willard Park Hospital for Children With Contagious Diseases to recover.

Before penicillin, “some kids lived, and some kids died” at the hospital, Zimbardo recalled. The children were not allowed to touch each other or their visiting family members, and thus spent days and weeks alone. To stave off boredom, Zimbardo learned to read and write, came up with games, and charmed his nurses into giving him extra sugar or butter or even a kind word.

Philip ZimbardoPhilip Zimbardo as a child. The future psychologist was hospitalized with pneumonia and whooping cough at the age of five.

Though bright, Zimbardo experienced discrimination throughout his life because of his family’s poverty and Italian roots. These experiences pushed him toward studying psychology.

“Being hurt personally triggered a curiosity about how such beliefs are formed, how attitudes can influence people’s behavior, how people can feel so strongly about something they know nothing about,” he remarked. “Could these people ever change? …And so I did research.”

Zimbardo attended Brooklyn College, and graduated in 1954 with a triple major in psychology, sociology, and anthropology. He then attended Yale for his master’s and his PhD, both of which were in psychology. After teaching psychology at Yale, Zimbardo taught at New York University and Columbia University, and became a professor at Stanford University in 1968.

There, Philip Zimbardo would conduct some of his most infamous experiments, including the Stanford Prison Experiment.

From ‘Broken Windows’ To The ‘Stanford Prison Experiment’

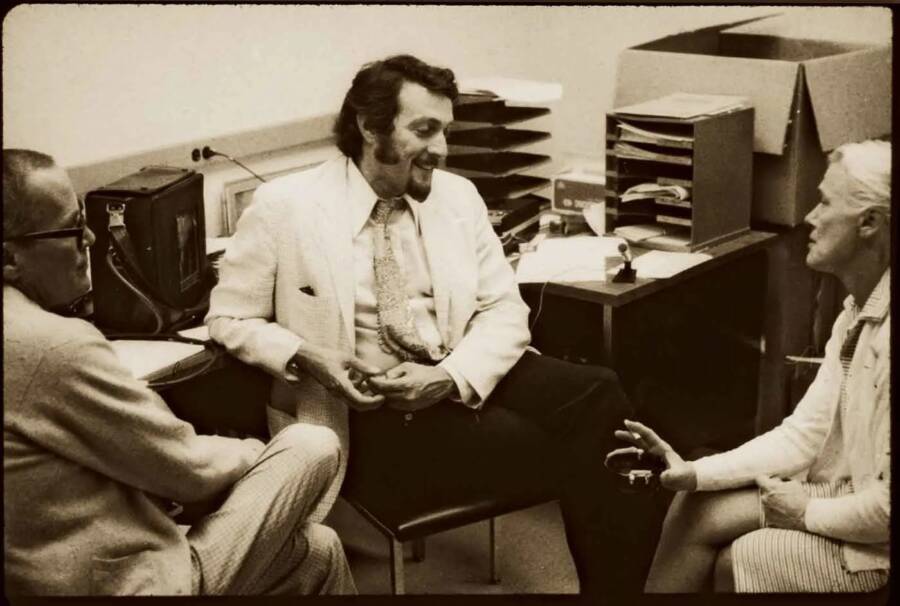

Philip G. Zimbardo Inc.Philip Zimbardo during the Stanford Prison Experiment.

At Stanford, Philip Zimbardo got to work testing his ideas about human behavior. In 1969, he conducted an experiment in which he left an abandoned car in two different places. The first he left in a New York City neighborhood with a high crime rate; the second he left in an affluent part of Palo Alto, California.

Zimbardo observed that the car in New York was stripped for parts and destroyed within the first 10 minutes. The car in Palo Alto, on the other hand, sat untouched for a week. Once Zimbardo smashed up the California car, however, it was targeted by thieves who stole its parts.

This experiment was the precursor for a controversial policing policy known as “broken windows.” The policy states that visible signs of crime — like broken windows — encourage more crime.

However, Philip Zimbardo is best known for a 1971 prison simulation known as the Stanford Prison Experiment.

“The Stanford prison experiment came out of class exercises in which I encouraged students to understand the dynamics of prison life,” Zimbardo explained to Psychology Today. “Some students took part in a mock prison for a weekend and the effects were very profound. So I said, ‘Well, let’s do this in a systematic way.'”

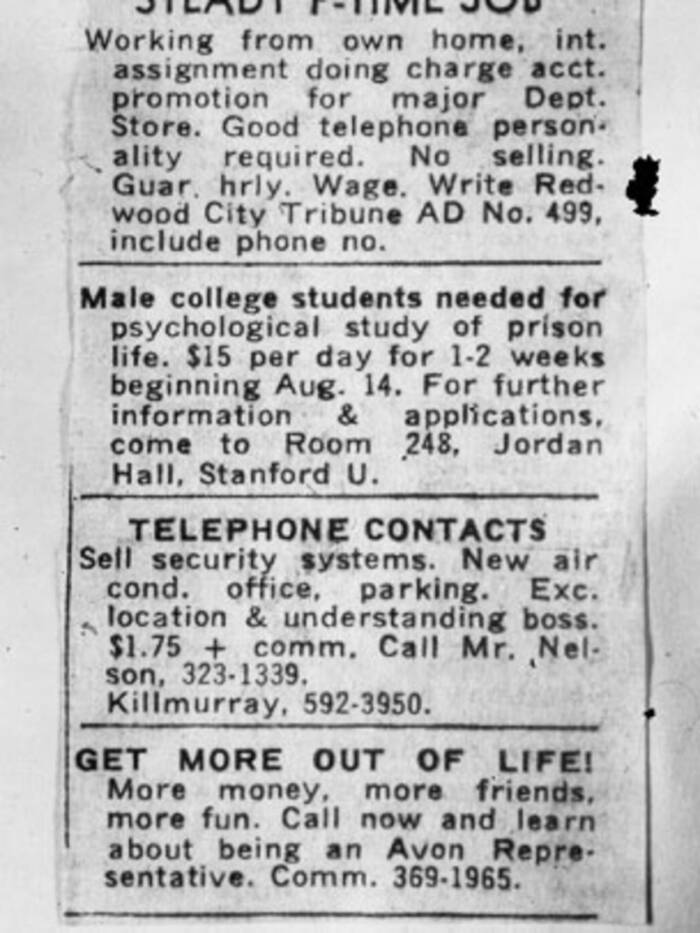

Philip G. Zimbardo Inc.An ad asking for volunteers to join the Stanford Prison Experiment.

Setting out to explore the dynamics between prison guards and prisoners, Zimbardo started the experiment by posting an advertisement that read, “Male college students needed for psychological study of prison life.” The volunteers would be paid $15 a day for one to two weeks.

Dozens signed up, and 24 were selected. A coin toss decided who would be a prisoner and who would be a guard — and then, the infamous experiment began.

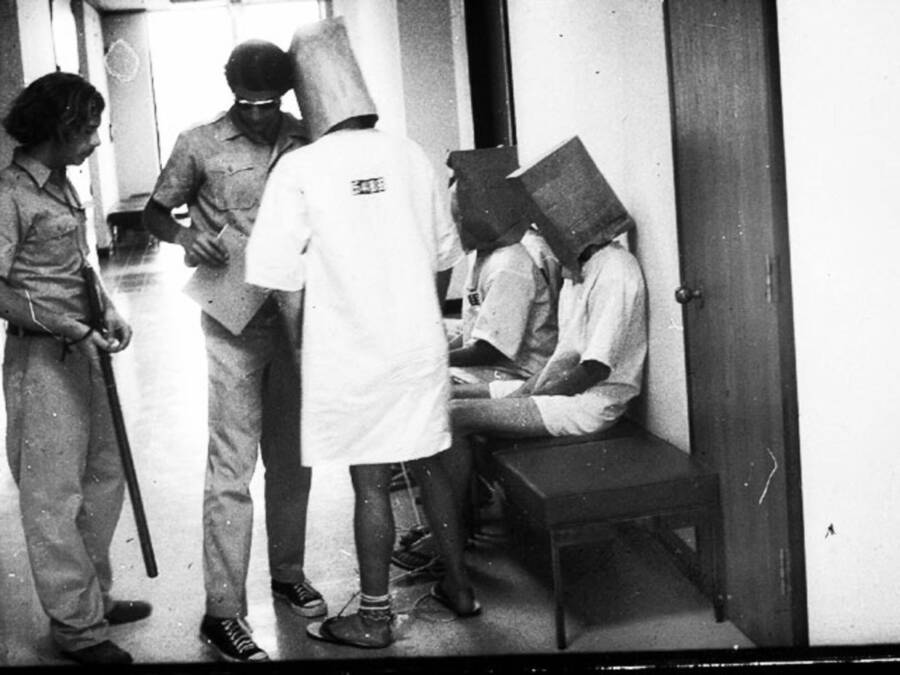

Over the next six days, the guards — who had free rein to keep the prisoners in line — became increasingly cruel. Wearing khaki uniforms and mirrored sunglasses, they woke the prisoners up early, stripped them of their clothing, and demanded they do pushups.

After the prisoners staged a rebellion on day two, the guards devised a system of punishments. They tossed “uncooperative” prisoners in solitary confinement, denied them bathing and food privileges, or forced them to wear paper bags on their heads. They also gave privileges to “cooperative” prisoners.

Philip G. Zimbardo Inc.During Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment, guards became increasingly cruel. Here, they’ve put paper bags over the heads of the “prisoners.”

Meanwhile, the prisoners became increasingly downtrodden. One prisoner told the others that they couldn’t quit the experiment, which caused mass panic. Another stopped eating and at one point began crying hysterically. Philip Zimbardo told this “prisoner” he could leave the experiment; the volunteer demurred that he didn’t want to be a “bad prisoner.”

Parents began to worry about their kids’ well-being and whether they were getting enough to eat. They started reaching out to Zimbardo, even offering to hire lawyers to get their sons out of “prison.” Still, Zimbardo only called off the experiment after his girlfriend, a PhD student, expressed shock at how poorly the volunteer prisoners were being treated.

Six days after it had begun, the Stanford Prison Experiment was over. But the experiment would cast a much longer shadow.

The Legacy Of Philip Zimbardo And The Stanford Prison Experiment

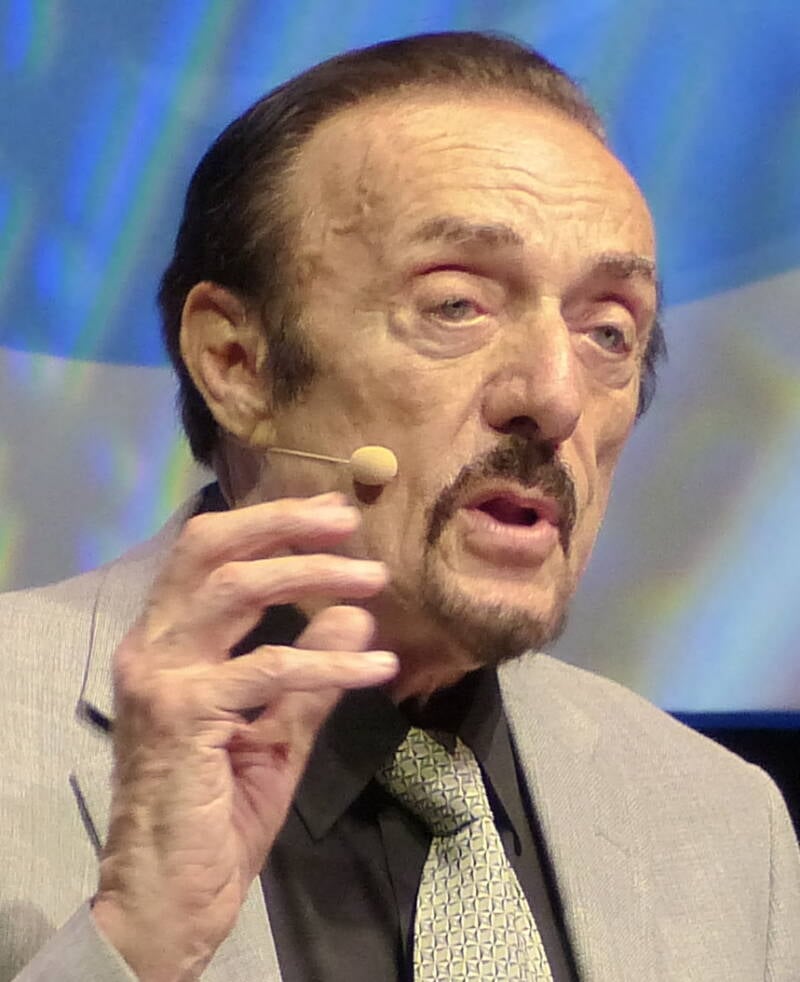

Elekes Andor/Wikimedia CommonsPhilip Zimbardo in 2017. He has steadfastly stood by the Stanford Prison Experiment, despite critiques of the study in recent years.

For decades, the Stanford Prison Experiment was held up as one of the most shocking and illuminating psychological experiments ever conducted. To many, the prison simulation was a revelatory examination of how people can be driven to evil simply by changes in their social roles and environment. However, it has been reevaluated in recent years.

In 2018, journalist Ben Blum wrote a critique of the study on Medium. He claimed that the experiment was manipulated by the researchers, including a research assistant who told a guard to act “tough” in hopes that the experiment would lead to criminal justice reform. And a prisoner who appeared to have a mental breakdown during the experiment told Blum that he’d simply been “acting.”

When Vox reached out to Philip Zimbardo about the experiment, he claimed that Blum had gotten it wrong. The guard, Zimbardo said, was being paid $15 a day to act like a guard and needed encouragement to do so. Zimbardo also denied that the prisoners had been “acting.”

In the end, Vox found his responses unconvincing; Philip Zimbardo stood by the results of his experiment.

“The single conclusion is a broad line,” he said. “Human behavior, for many people, is much more under the influence of social situational variables than we had ever thought of before. I will stand by that conclusion for the rest of my life, no matter what anyone says.”

That said, the Stanford Prison Experiment is hardly the only thing Zimbardo accomplished. In the aftermath, he also conducted studies on time perspective, military culture, shyness, and the psychology of evil. But Philip Zimbardo acknowledges that the Stanford Prison Experiment is one of the things he’ll be remembered for.

“The Stanford prison experiment is obviously one of my main legacies, 30 years later,” he remarked to Psychology Today.

“In part, its enduring value has to do with the dramatic transformation of human nature: In only a few days, ordinarily good boys were behaving in either evil, sadistic ways like guards or pathologically breaking down like prisoners. And it just violated all of our common assumptions about stability of character and the power of individual dispositions on behavior. It highlighted the powerful control that situational variables could exert.”

After reading about Philip Zimbardo and the Stanford Prison Experiment, discover the stories of some of the most horrifying psychological experiments ever conducted. Or, learn about phrenology, the study of facial features that’s now been debunked as pseudoscience.