Totem poles serve a wide variety of purposes for the Indigenous groups that carve them, from illustrating a family's lineage to ridiculing people who have wronged the tribe.

travel4pictures / Alamy Stock PhotoColorful totem poles on display at Stanley Park in Vancouver.

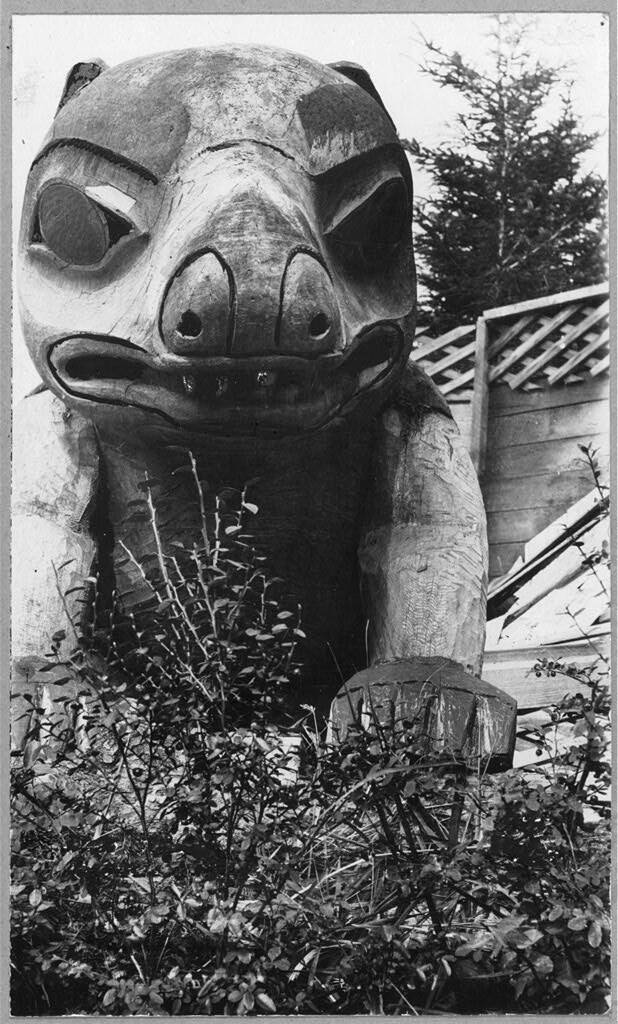

Totem poles were first created by several Indigenous tribes of the Pacific Northwest who resided mostly in modern-day Alaska and British Columbia. While the exact origins of totem pole carving are unclear, written records first appeared in the late 18th century, and oral records date back even further.

Typically made from red cedar, the totem poles ranged in height from nine to over 100 feet and served various purposes. Some held the remains of the deceased, others acted as decorative doors or support beams for houses, and a few were even made to ridicule people who had wronged a tribe.

Throughout the 19th century, the arrival of European settlers contributed to the decline of totem pole creation. European missionaries and legislation, such as Canada’s Potlatch Law of 1884, discouraged or explicitly banned the tradition, resulting in many poles being sold, destroyed, or left to decay. Despite this, totem poles later gained popularity among tourists, and they became symbols of conflict between Indigenous tribes and outsiders.

By 1951, the Potlatch Law was overturned, allowing Pacific Northwest tribes to revive their totem pole traditions. Indigenous artists renewed the art form, creating new poles to commemorate important events or honor deceased relatives. Today, totem poles continue to hold cultural significance and are celebrated for their historical and artistic value.

Inside The Cultural Significance Of Totem Poles

It's a common misconception that totem poles were created as idols to worship. There are around seven principal types of totem poles, all with practical or cultural purposes. Heraldic or crest poles stand outside of the homes of important tribal leaders and tell the story of their family's lineage. Welcome poles, which are often located on the edge of a stream or a beach, are also used by some tribes to mark territory and greet — or intimidate — visitors.

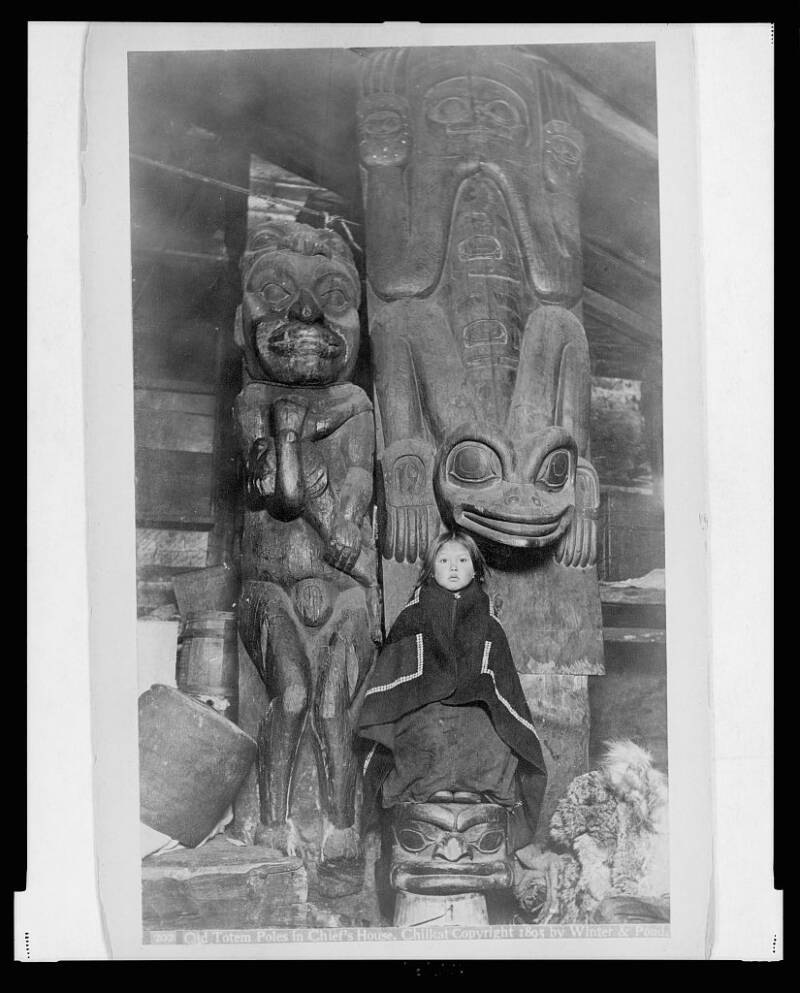

House posts are interior totem poles that support the roof of a longhouse while also telling stories of the homeowners' history. Then there are portal posts, which are large enough for a person to walk through and can serve as the entrance to a home.

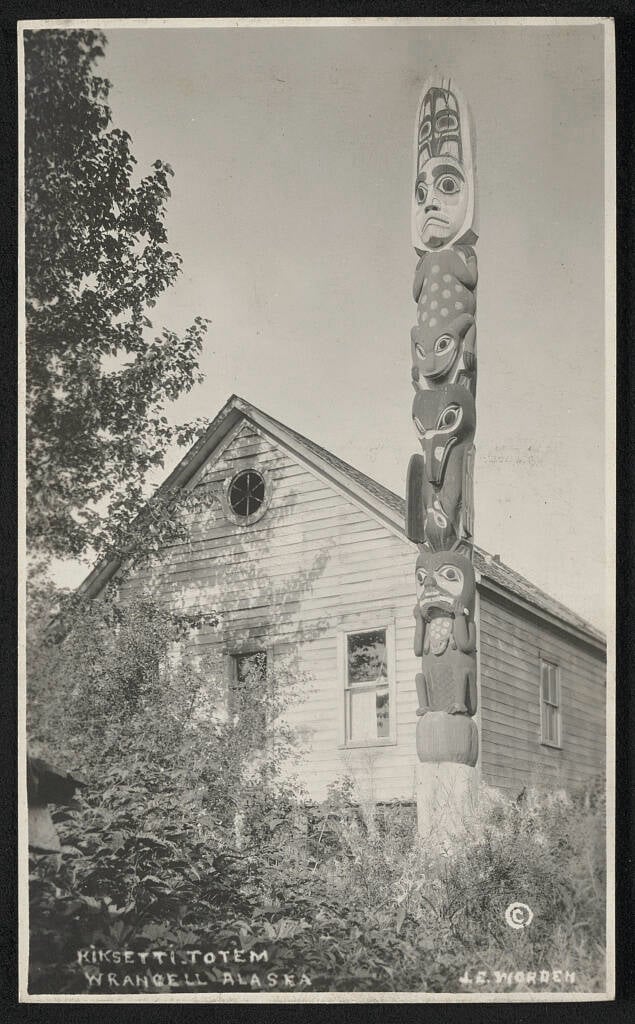

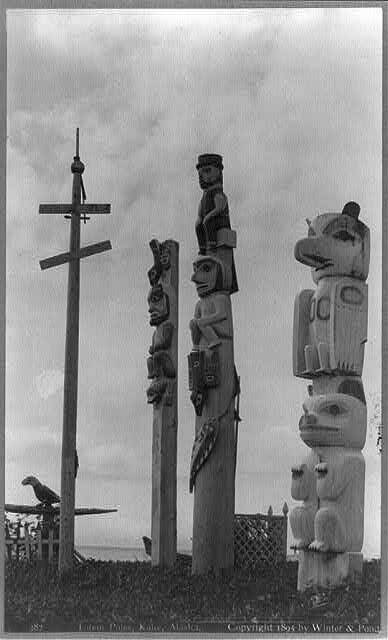

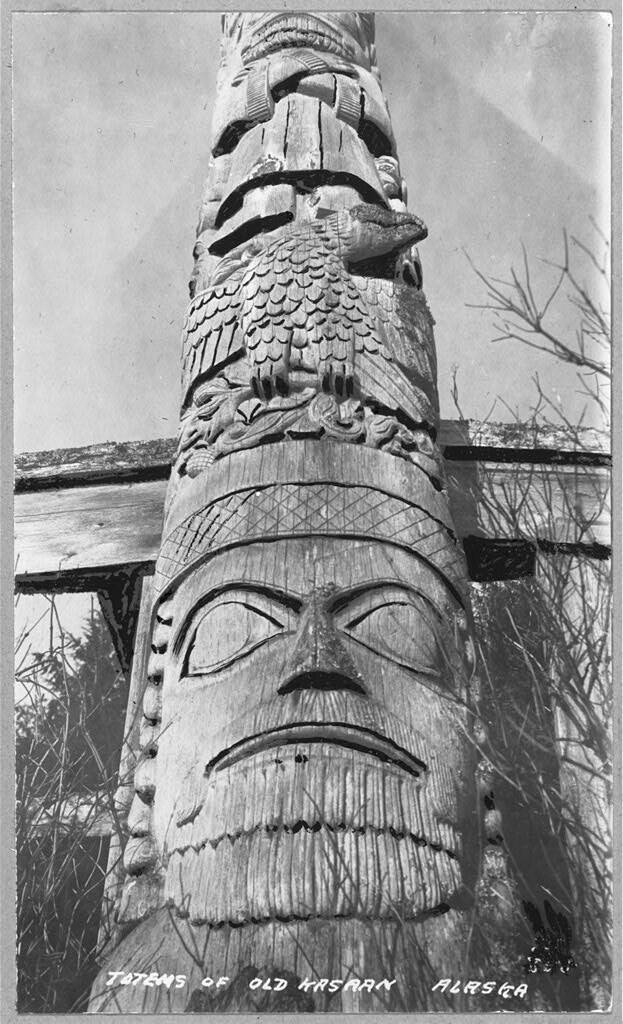

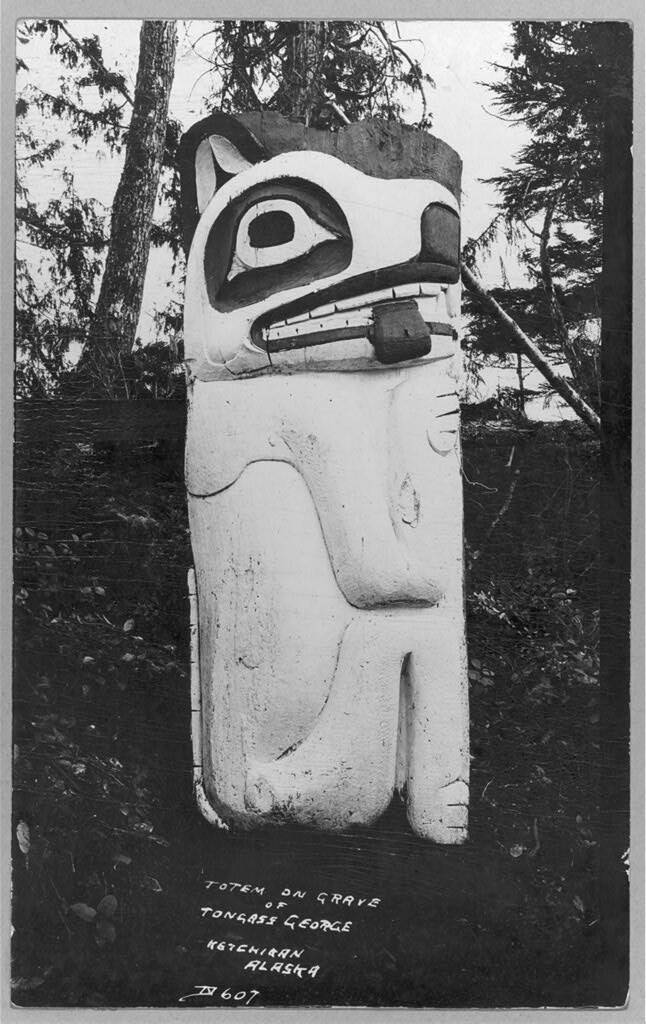

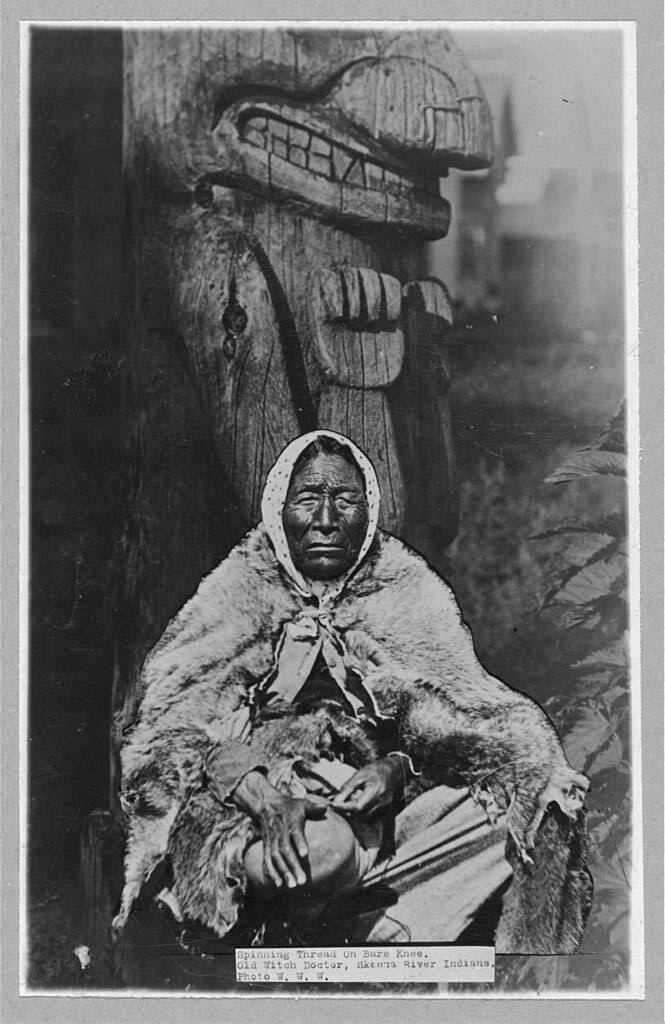

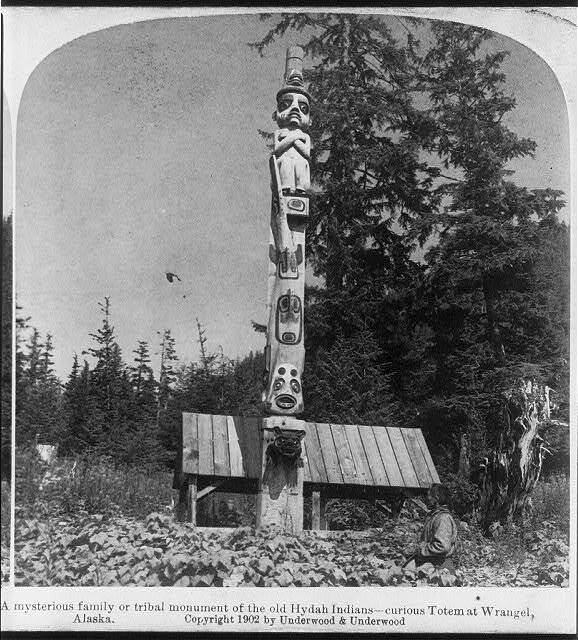

Library of CongressA totem pole in Hydaburg, Alaska, in the early 20th century.

Mortuary poles can act as grave markers or hold the remains of the dead. Similarly, memorial poles honor the deceased and identify the member who has taken over as their successor in the community. These poles can also commemorate important events within a tribe.

Perhaps the most unique type of totem pole is the ridicule pole, which is used to shame people who have wronged a tribe. This usually entails an unpaid debt, but perhaps the most famous ridicule pole was created for an entirely different reason. The "Seward Pole" at the Totem Park in Saxman, Alaska, depicts former Secretary of State William H. Seward.

According to the Alaska Historical Society, the original version of the totem pole was created in the 1880s, more than a decade after the Tlingit people honored him at a potlatch — a type of ceremonial feast — in 1869. He never returned their generosity, and they erected the pole to shame him for the lack of recognition.

It's well known that totem poles play an important role in the societies of these Indigenous tribes, but how did the tradition of carving the posts begin?

The Long History Of Totem Poles In The Pacific Northwest

The first totem poles were created by Pacific Northwest tribes like the Haida, Tlingit, Nuxalk, Tsimshian, Kwakwaka'wakw, and Coast Salish. These Indigenous people mainly lived in British Columbia, with some territories stretching into southern Alaska and northern Washington.

While it is unclear when the practice of carving the poles originally began, the first written accounts appeared in 1791. That year, according to the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle, a sailor named John Bartlett drew a picture of a Haida totem pole on Langara Island off the coast of British Columbia.

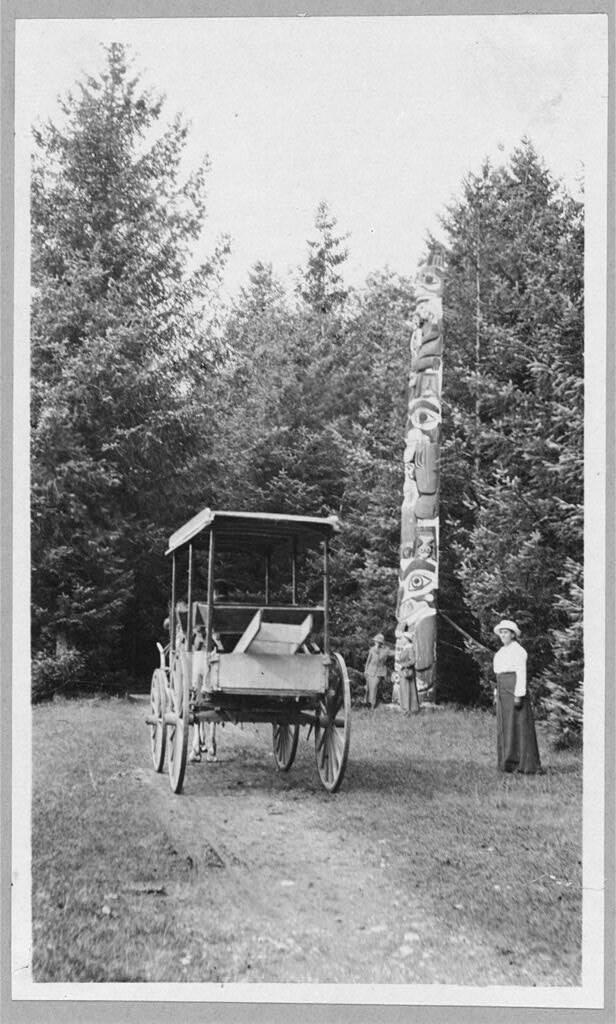

James Crippen/Wikimedia CommonsAn example of a modern Tlingit pole raising ceremony in Klawock, Alaska.

Totem poles were traditionally carved by highly-trained men. Tribe members would carefully select a tree and hold a gratitude ceremony prior to cutting it down. Western red cedars were preferred due to the fact that they were resistant to rot and easy to carve into.

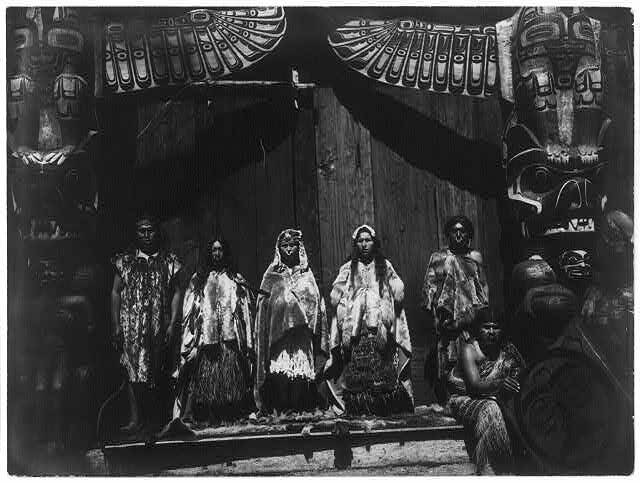

After the pole was completed, the tribe would hold a raising ceremony with an opulent feast called a potlatch. There, tribe leaders would tell stories about the carvings on the totem pole and reveal the meaning behind them.

However, when Europeans began settling in the area in the 18th and 19th centuries, they were determined to Christianize the Indigenous people they came across — and totem poles saw a rapid decline because of it.

The 1884 Potlatch Law And The Revival Of The Art Form

European settlers in the Pacific Northwest infamously ripped away the culture of Native American and First Nations people in the name of religion. Missionaries to the region saw totem poles and the potlatches that accompanied their creation as paganistic and condemned them.

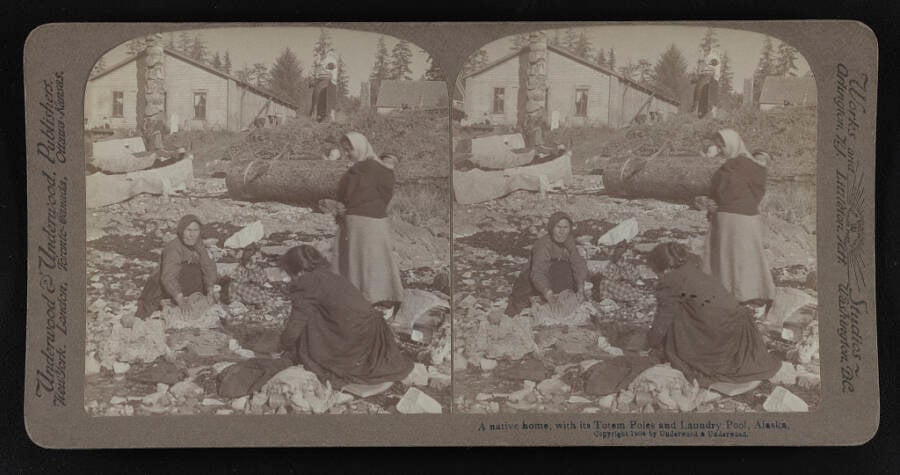

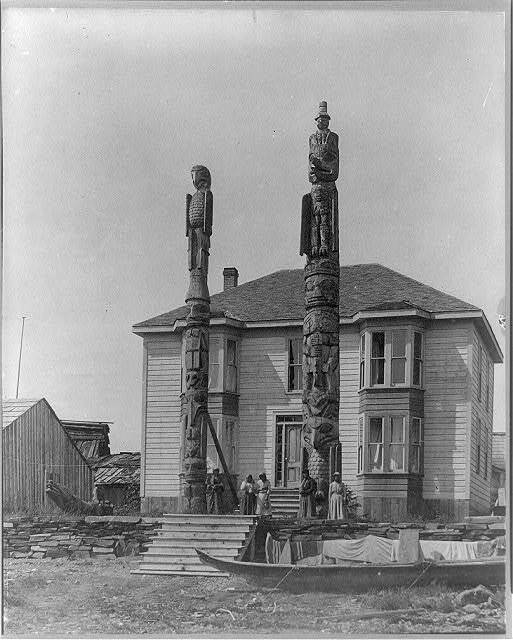

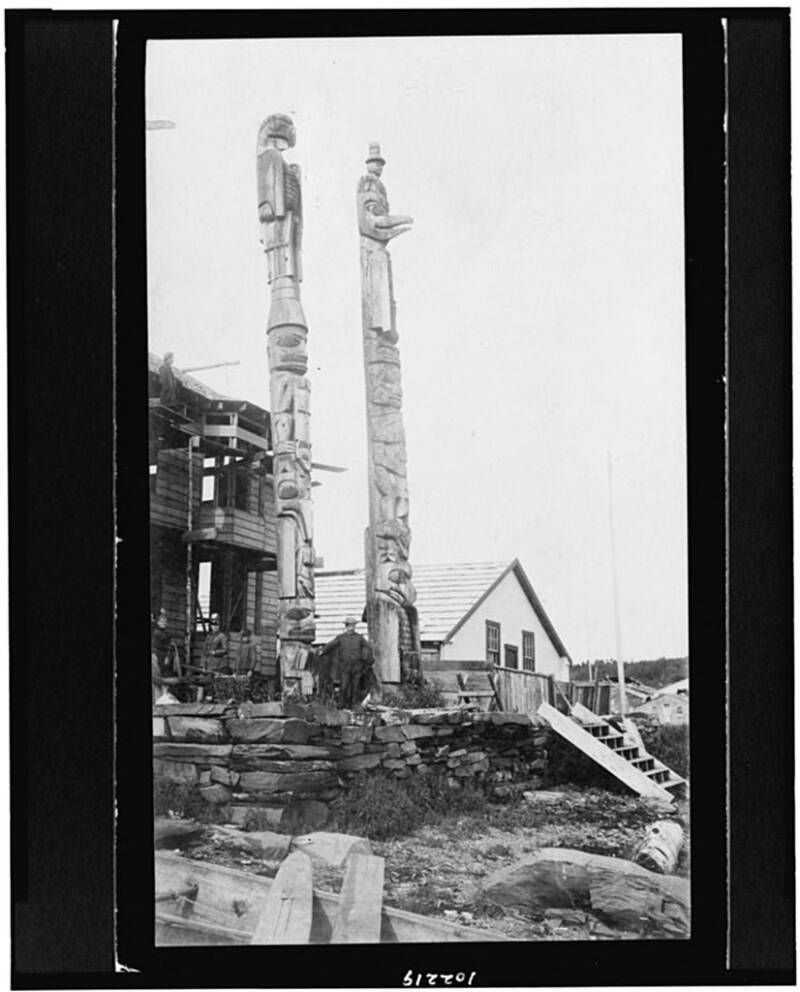

Library of CongressMembers of the Harriman Alaska Expedition posing in front of totem poles in Cape Fox in 1899.

Many 19th-century totem poles were sold to museums, left to decay, or cut apart for their wood. In 1884, the Canadian government outright banned potlatches. The law read: "Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the 'Potlach' or in the Indian dance known as the 'Tamanawas' is guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be liable to imprisonment... and any Indian or other person who encourages... an Indian or Indians to get up such a festival or dance, or to celebrate the same... is guilty of a like offence."

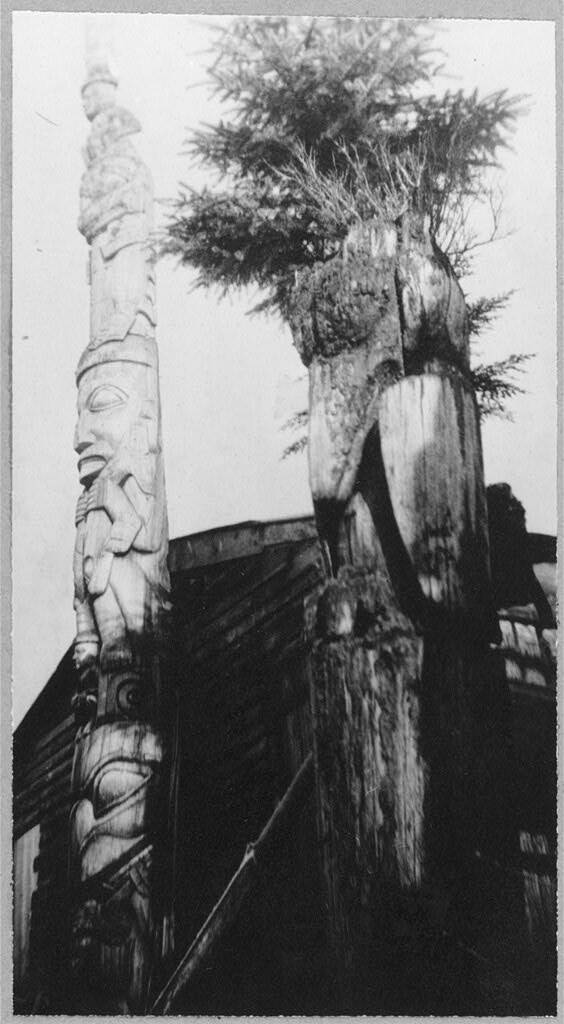

While totem pole carving was never officially banned, the practice declined since the traditional ceremonies surrounding their creation couldn't be held. However, totem poles also rose to popularity outside of the Pacific Northwest during this time. Tourists flocked to the region to view them and even purchased miniature models as souvenirs.

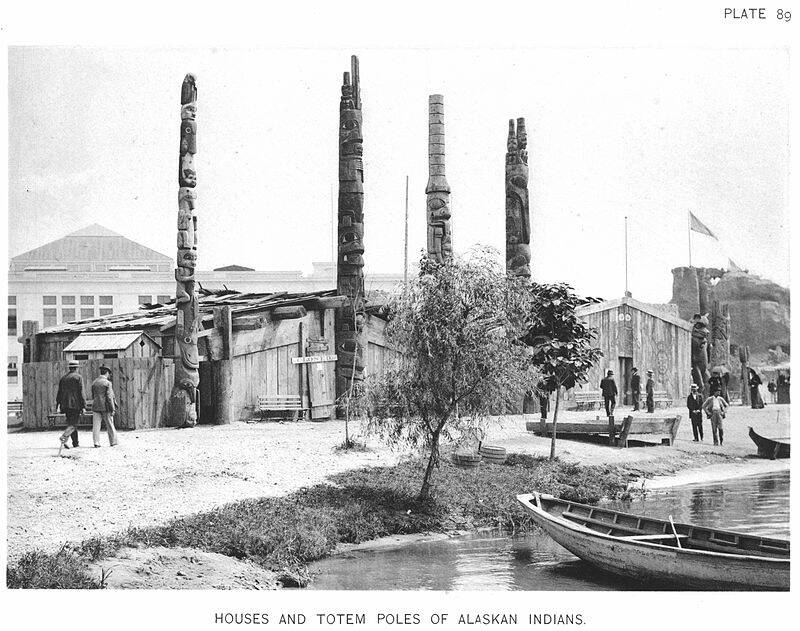

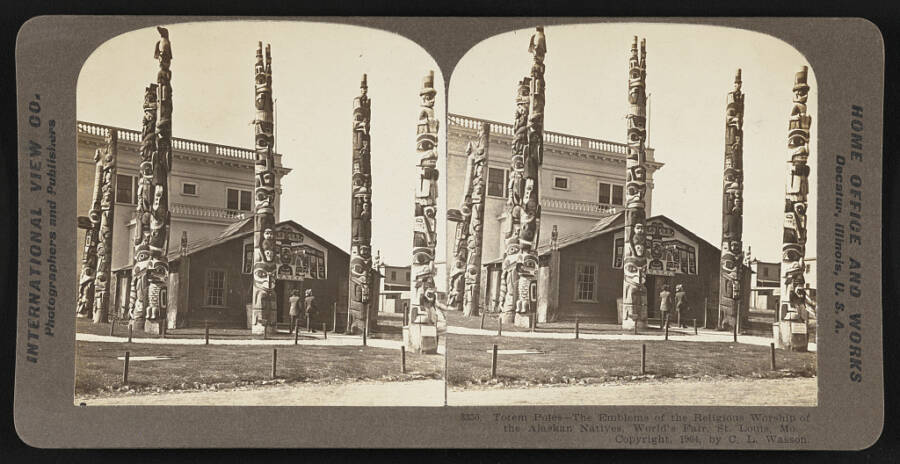

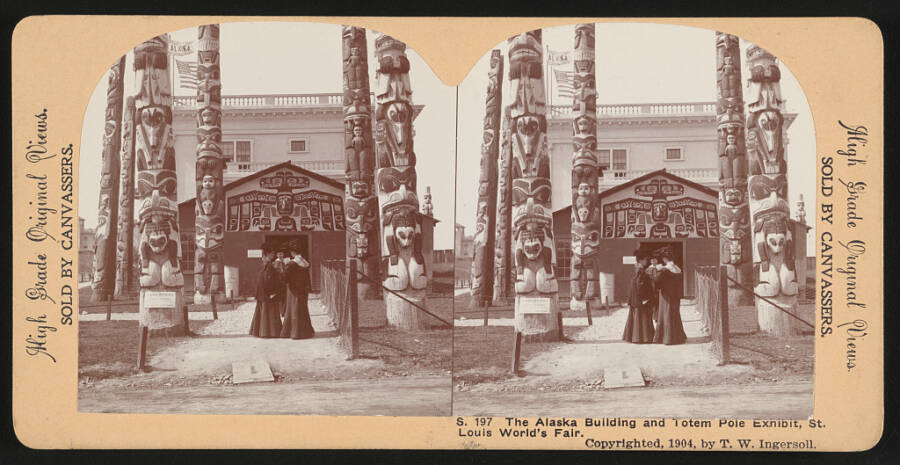

The intricately carved posts went on display across at world's fairs and expositions across the country throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Then, in the first half of the 1900s, many were returned to Alaska and displayed in newfound totem parks.

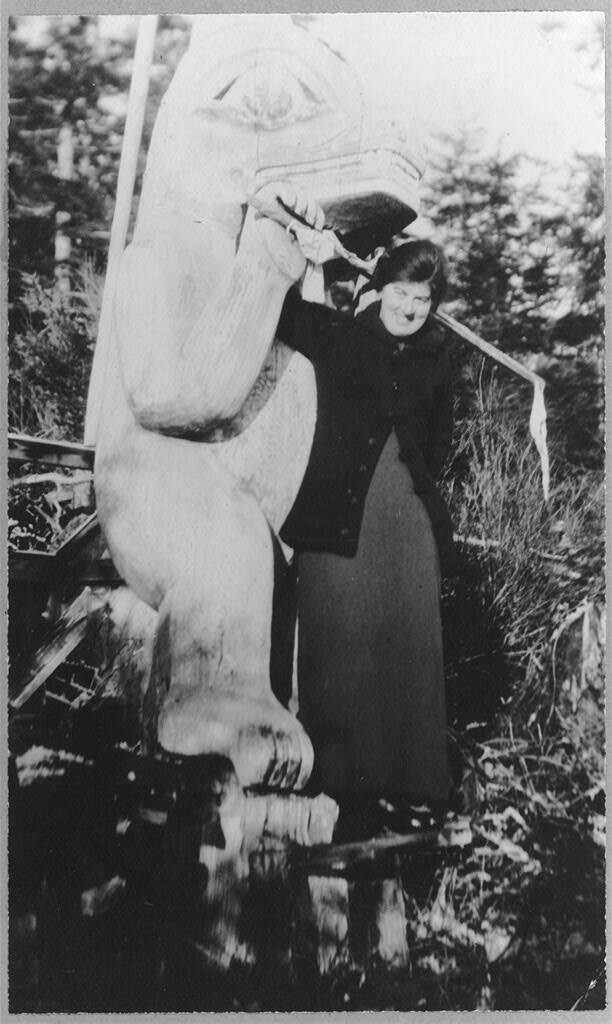

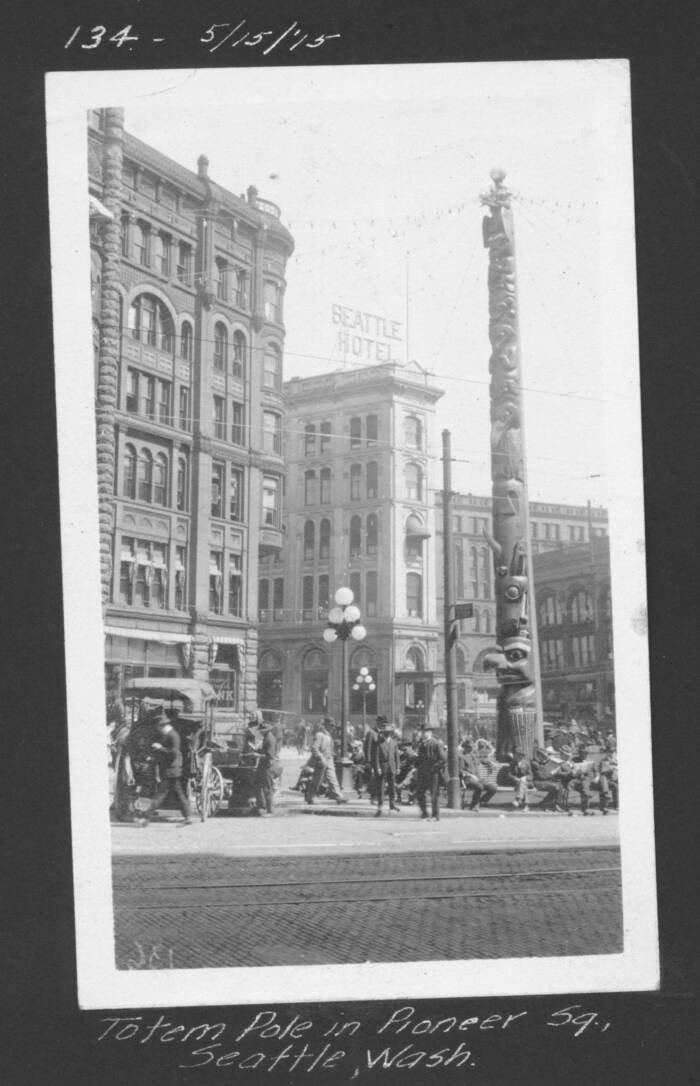

University of WashingtonThis totem pole was carved around 1790 to honor a Tlingit woman who had drowned, but it was later stolen by a businessman visiting Alaska and erected in Pioneer Square in Seattle.

In 1951, the Potlatch law was overturned, and Indigenous tribes were allowed to hold their ceremonial feasts once again. The act of carving totem poles was revived by a new generation of artists. More poles were erected, and others were repatriated from the collectors and museums they'd been sold to in the 19th century.

Today, the cultural icons stand both as a tribute to the rich culture of Native American and First Nations people and a reminder of their tragic history.

After reading about the history of totem poles, go inside the story of nine of the most powerful Native American warriors in history. Then, read about seven of the scariest creatures in Native American folklore.