After Itaru Sasaki built the first wind phone in Japan in 2010, the concept of a disconnected phone where mourners can share final words with lost loved ones has spread across the world.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Ōtsuchi Wind Phone in 2018, before the installation of a new aluminum phone booth.

Perched on a hill in Ōtsuchi, Iwate Prefecture, Japan, there sits a telephone booth overlooking the sea. Inside, there is a black rotary phone, disconnected from any network. It is known as kaze no denwa, or “Wind Phone.” It’s a sanctuary where visitors can “call” their lost loved ones to share words left unsaid or seek a connection beyond the physical realm.

This wind phone, the first, was installed by a man named Itaru Sasaki, a garden designer who lost his cousin to cancer in 2010. The disconnected phone booth became his personal coping mechanism, as Sasaki felt that by speaking into the wind, his thoughts could reach his departed cousin.

But months later, a national tragedy compelled Sasaki to open his “Phone of the Wind” to the public. In the aftermath of the catastrophic 2011 earthquake and tsunami that claimed the lives of more than 19,000 people in the Tōhoku region, Sasaki invited others to use his wind phone to grieve their losses, speak final words to lost loved ones, and find closure.

Since then, Sasaki’s wind phone has been visited by more than 30,000 people — and his is no longer the only one. According to a map from My Wind Phone, similar booths have been installed across the world, with 265 in the United States alone and another 111 worldwide.

Clearly, something about Sasaki’s idea of the wind phone has resonated with people across cultures — perhaps a testament to the universality of grief and the search for meaning that follows.

Itaru Sasaki’s ‘Phone Of The Wind’

The story of the wind phone began in Ōtsuchi, a fishing village in Japan’s Iwate Prefecture. In 2010, it had a population of 16,000 people, including a man named Itaru Sasaki.

Sasaki was a garden designer who had a close relationship with a cousin. His cousin, a calligrapher and martial arts instructor, told Sasaki in 2010 that he had been diagnosed with stage four cancer and had just three months to live. When his cousin passed, Sasaki looked for ways to deal with his grief.

Wikimedia CommonsThe wind phone in Itaru Sasaki’s garden.

He had already installed an empty phone booth in his garden as decoration, but after his cousin’s passing Sasaki began to envision a new purpose for the phone both. He began to see it as a way to “speak into the wind,” as it were, and have conversations with his deceased cousin the afterlife.

“Life is only, at most, 100 years,” Sasaki told The Believer’s Tessa Fontaine in 2018. “But death is something that goes on much longer, both for the person who has died and also for the survivors, who must find a way to feel connected to the dead. Death does not end life. All the people who are left afterward are still figuring out what to do about it.”

By the time Sasaki finished installing his wind phone in December 2010, Ōtsuchi, located at the base of Sasaki and his wife’s hilltop home, looked the same as always. It curled along the coast, full of businesses and homes.

But three months later, it was all but gone.

The Unprecedented Destruction Of The 2011 Tōhoku Tsunami

Wikimedia CommonsŌtsuchi in the wake of the 2011 tsunami that devastated the coast of Japan.

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.1 earthquake tore across the seafloor near Japan, sending waves reaching up to 128 feet hurtling toward the Japanese coast. The waves crashed into the city of Miyako first, while water inland in Sendai spread across six miles.

Some 217 square miles of the Tōhoku region were flooded with water. Hospitals, schools, businesses, homes, railways, and nearly everything else in the water’s path was destroyed. The devastating torrent also caused a cooling system failure at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, leading to an infamous meltdown that displaced more than 150,000 people.

The tsunami itself, meanwhile, claimed the lives of more than 19,000 people. Millions more lost access to running water and electricity, and more than 120,000 buildings were destroyed in just a few minutes. Japan’s Reconstruction Agency estimated the total financial damage to be around $199 billion — The World Bank put it higher, at $235 billion.

Wikimedia Commons12-story-high waves barreling into the city of Miyako on March 11, 2001.

Those who survived were forever changed. Their homes had been destroyed, their livelihoods taken from them, and, in many cases, their loved ones too. Official figures released in 2021 reported 19,759 deaths, 6,242 injured, and 2,553 still missing.

Grief manifested in strange ways for many people, as it often does. Months later, many reported seeing the spirits of tsunami victims across the Japanese coast, a phenomenon closely related to yōkai, the not-quite-spirits of Japanese folklore. For many others, though, grief left them lost.

So, Itaru Sasaki opened his garden to the public. He invited mourners to come and use his wind phone to speak to their lost loved ones.

How The Wind Phone Became A Site Of Pilgrimage

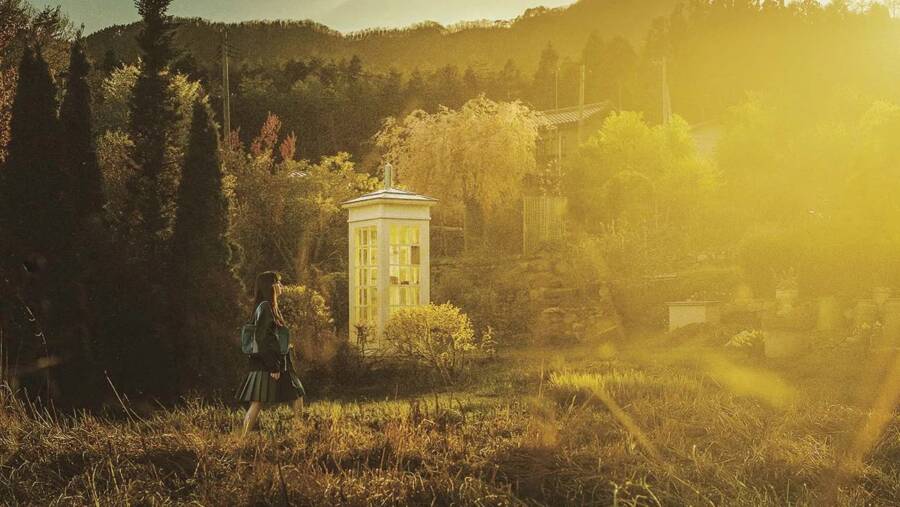

Broadmedia StudiosA scene from the film Voices in the Wind, which features the wind phone.

In the years after Itaru Sasaki opened his wind phone to the public, 30,000 people — and counting — descended on his garden to have a final conversation with their lost loved ones.

“It all happened in an instant, I can’t forget it even now. I sent you a message telling you where I was, but you didn’t check it,” Kazuyoshi Sasaki told his wife Miwako through the wind phone, as Reuters reported in 2021.

He continued: “When I came back to the house and looked up at the sky, there were thousands of stars, it was like looking at a jewel box. I cried and cried and knew then that so many people must have died.”

Kazuyoshi Sasaki had spent days searching for his wife, sifting through the rubble of their home, visiting makeshift morgues and evacuation centers. He never found her. Like many others, the suddenness of the tsunami and the devastation it brought meant he never got to say goodbye.

“It’s not like anything else,” Sasaki noted. “It isn’t therapy. It isn’t the same as the thing you say to your friend over your second glass of wine about wishing you could talk to your dead mother about something. It isn’t praying. It isn’t talking to a loved one who also knew the dead. You pick up the phone and your brain has readied your mouth to speak. It’s wired. We do it all the time. You don’t think what it is you want to say, you just say it. Out loud.”

Those who lost loved ones in the tsunami weren’t the only ones who found the wind phone cathartic. For many, the COVID-19 pandemic created a similar need as the 2011 tsunami. Lives were tragically and suddenly cut short; many around the globe were robbed of a last goodbye. That collective grief led organizers to reach out to Sasaki to set up wind phones in Europe and the United States.

There are now more than 300 other wind phones scattered about the globe.

Wikimedia CommonsThe interior of a wind phone in Amsterdam.

“There are many people who were not able to say goodbye,” Itaru Sasaki remarked. “There are families who wish they could have said something at the end, had they known they wouldn’t get to speak again… Just like a disaster, the pandemic came suddenly and when a death is sudden, the grief a family experiences is also much larger.”

But wind phones, perhaps, can help mourners process their loss.

After learning about how the wind phone has helped people deal with grief, learn about the fascinating way in which the Toraja people of Indonesia honor their dead. Or, read about the town of Nagoro, Japan, where the dead are replaced with life-sized dolls.