Throughout industrial Britain and America, young women employed at matchmaking factories and working closely with toxic chemicals developed a brutal disease known as “phossy jaw" — which caused their jawbones to literally rot.

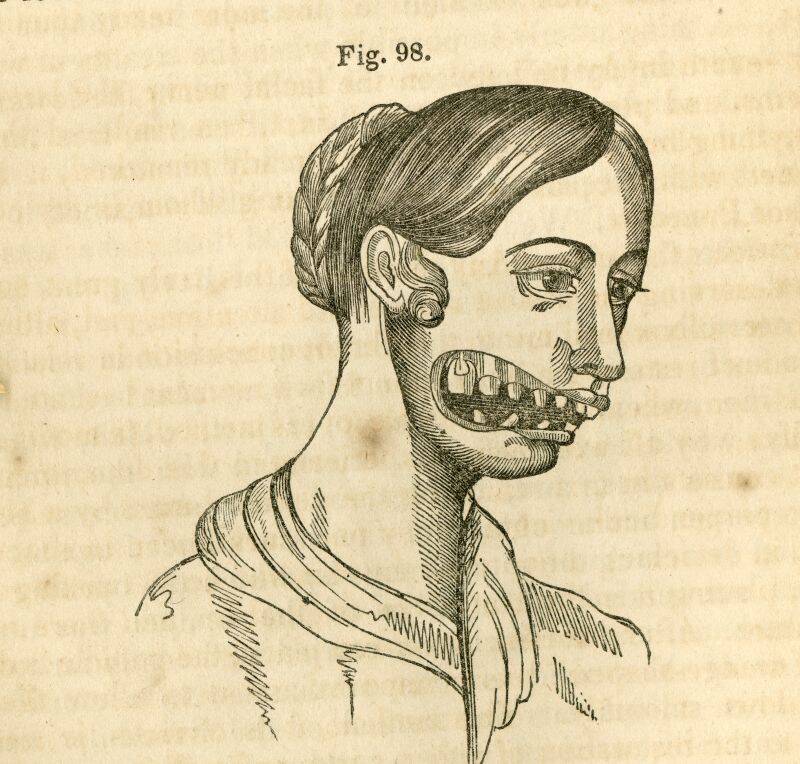

Wikimedia CommonsA late 19th-century photograph of a matchstick girl suffering from phossy jaw.

In 1855, a 16-year-old factory worker named Cornelia visited a doctor in New York with a toothache on the right side of her lower jaw.

According to the teen, she had been working at least eight-hour days at a match-packing factory for the last two years but was now in too much pain to even eat. It didn’t occur to her that her constant proximity to the toxic white phosphorous that was used to make matches had caused a horrifying condition in her face known as “phossy jaw.”

None the wiser, her doctor lanced her gums, removed a tooth, and sent her back to the factory.

But Cornelia would return to the doctor at Bellevue Hospital in worse condition. A hole had formed in her jaw and it discharged sickly pus. Finally, in a painful, arduous surgery, the doctor removed her entire lower jaw.

Cornelia was but one in hundreds of young women who suffered from “phossy jaw” at the turn of the 20th century. In industrial factories, so-called “matchstick girls” were employed to dip wooden sticks into white phosphorus for hours upon end to create “strike-anywhere” matches. But such close proximity to white phosphorous caused their jawbones to deteriorate.

Matchstick girls struggled to bring awareness to their suffering, but it would take decades to finally ban the use of white phosphorus altogether. However, their struggle was not in vain, as Cornelia’s case and the cases of those who suffered for the sake of industry galvanized the fight for workers’ rights.

The Price Of Better Matches Came At The Cost Of Phossy Jaw

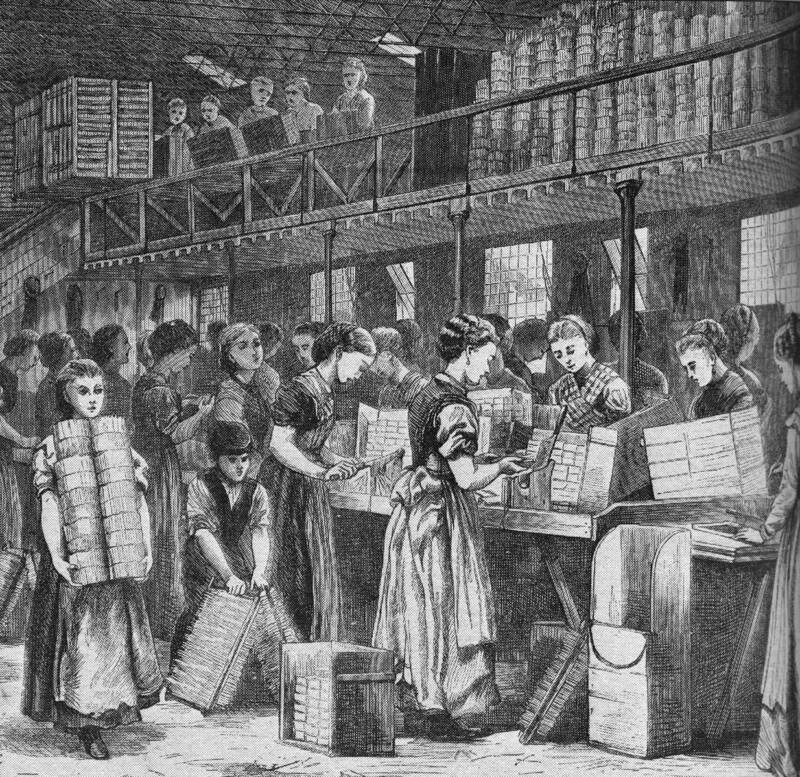

Wikimedia CommonsThe crowded conditions in 19th-century factories meant matchstick girls breathed in white phosphorus in toxic amounts.

Matchmaking was a common trade across early 19th-century England and America, and matchmakers worked tirelessly to find new innovations in match technology. Enter: white phosphorous.

Though notoriously toxic, the chemical could be rendered into a paste that could be lit on any surface with just a bit of friction. These so-called “strike-anywhere” matches, also known as lucifer matches, became incredibly popular — and the industry to create them became equally profitable.

Although factory owners knew that prolonged exposure to white phosphorous could cause the necrosis of the human jaw, they continued to use it anyway — and employed young women and girls in their factories for 10 to 15-hour days.

Every morning, factory workers would arrive to make matches. Mixers would stir up phosphorus with glue and color, while driers would line up thousands of matchsticks in a frame. Then, dippers would dunk the rack of matches into the phosphorus mixture. After the matches dried, other workers would box them up.

One dipper might create as many as 10 million matches in a single day — all while exposing themselves to deadly chemicals.

Factory owners implemented new, albeit minor, procedures to limit the harm. In one factory, employees had to wash their hands after work. Dippers covered their mouths. Other factories tried to improve ventilation.

But white phosphorus continued to poison workers.

Matchmaker’s Leprosy Plagues Hundreds Of Workers

Wikimedia CommonsPhossy jaw was also referred to as “Matchmaker’s leprosy,” in part because victims left disfigured by the disease were often ostracized from their workplaces.

The first recorded case of phossy jaw was observed in 1838 in a Viennese matchstick girl. By 1844, a doctor in Vienna reported 22 more cases of phosphorus necrosis of the jaw, and yet the industry boomed.

Dr. James Rushmore Wood of New York started to write about phossy jaw in 1857 after treating 16-year-old Cornelia. He noted that the first sign of phossy jaw was pain in the jaw, followed by abscesses along the gums. Sometimes victims’ gums also glowed in the dark. In serious cases, the necrosis completely destroyed the jaw and caused brain damage. Without removing the jaw entirely, phossy jaw could prove fatal.

His procedure on Cornelia’s jaw, which involved using a 19th-century chain saw described as something akin to a “cheese wire,” was not initially successful. Wood had to perform a second operation and monitor his patient for a month before he declared Cornelia “cured.”

Other victims weren’t as lucky as Cornelia. A 22-year-old named Barbara, who worked in a match factory for over three years, died less than three months after the onset of her symptoms.

Wikimedia CommonsA woman with phossy jaw.

Then there was Annie, a 13-year-old who noticed that her hands started glowing after working in a match factory for four years. Like Cornelia, she underwent jaw removal surgery. Maggie, 23 years old, continued to work in the match factory after undergoing five operations to remove her jaw.

It was estimated that approximately 11 percent of those exposed to white phosphorus fumes developed phossy jaw. The United States reported more than 100 cases alone by 1909.

With little reaction from factory owners, workers were forced to take the problem into their own hands.

British Matchgirls Strike In 1888

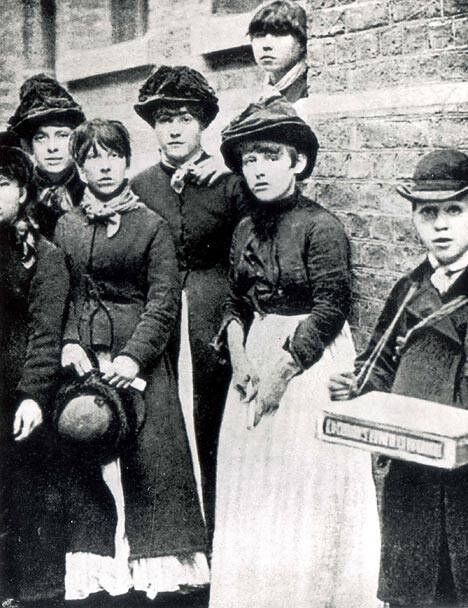

Wikimedia CommonsBryant & May factory workers who participated in the 1888 strike.

In June 1888, women’s rights activist Annie Besant wrote about the plight of Britain’s matchstick girls.

In her article “White slavery in London,” Besant chronicled the conditions in match factories and the horrifying realities of phossy jaw. She pointed out unfair practices in the factories like low wages and fines for dirty feet, untidy workspaces, and setting burnt matches on a bench.

Girls were fined for talking or arriving late, and one worker lost a quarter of her week’s wages when she pulled her fingers out of a machine so that they wouldn’t be severed.

Wikimedia CommonsAnnie Besant was a British activist who led the charge to reform working conditions for matchstick girls.

By the time of Besant’s writing, several countries had already banned the use of phosphorus in factories. But not Britain, where the government said banning the chemical would amount to a restriction on free trade.

Besant’s article created conflict between Bryant & May, a major London match factory, and their workers. Bryant & May pressured workers to sign a statement denying Besant’s claims, and when some of the workers refused, Bryant & May fired them.

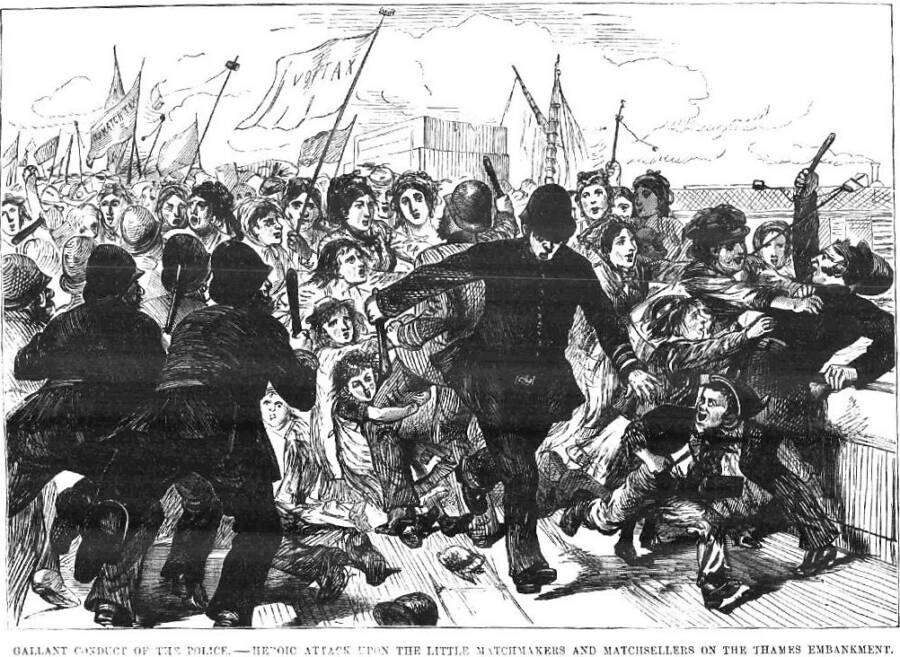

The company’s actions triggered the Matchgirls’ Strike of 1888 during which 1,400 factory workers refused to work and protested factory conditions instead.

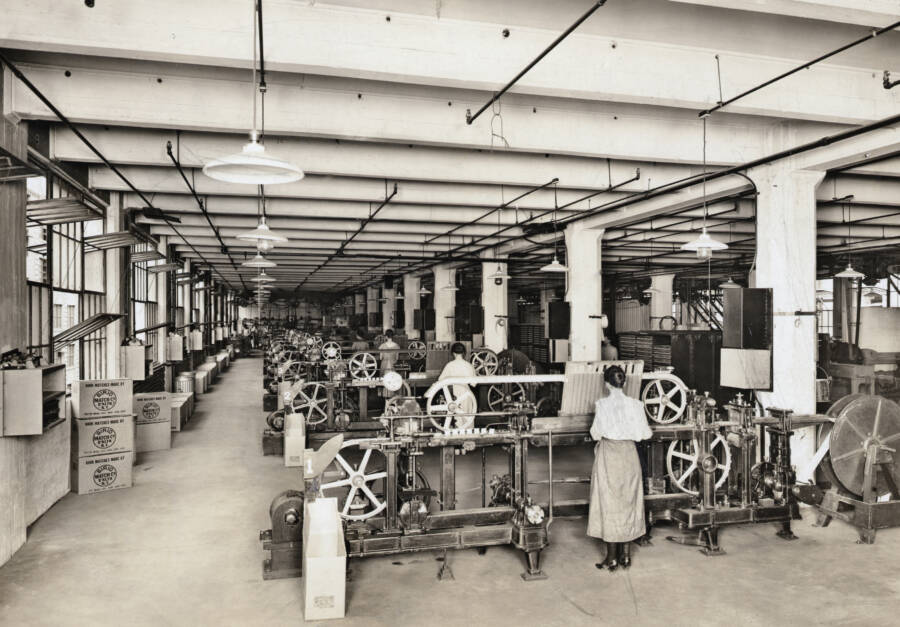

Getty ImagesWomen working at machines to manufacture matches at the Sirio Match Co. in Brooklyn, New York. Circa 1915.

Political activist and militant suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst joined in the strike. “It was a time of tremendous unrest, of labor agitations, of strikes and lockouts,” Pankhurst recalled. “It was a time also when a most stupid reactionary spirit seemed to take possession of the Government and the authorities.”

The striking match workers won some concessions from Bryant & May, including an end to the unfair fines. But the factory continued to use white phosphorus.

The Fight For Safer Working Conditions Continues Through The Turn Of The Century

Wikimedia CommonsA demonstration of matchmakers in 1871.

Though phosphorous wasn’t yet outlawed in England, the 1888 strike brought new attention to the horrific conditions in many factories. Journalists chronicled the abuses, including an attempted cover-up of the seriousness of phossy jaw.

In 1892, the Star published an exposé on phossy jaw at Bryant & May. The paper revealed that Bryant & May forced one of its workers with phossy jaw to quit and continued to pay her wages as she recovered.

But once she was cured, they refused to restore her job and other match factories declined to hire her because of her scarred appearance following the disease. Employers claimed a woman missing half her jaw would frighten the other workers.

Wellcome ImagesBryant & May matchboxes.

Even after hearing of the cover-up, the British government chose not to ban white phosphorus, which had been harming workers for more than half a century by this point. But in 1898, the British government finally slapped Bryant & May with a fine of 25 pounds, the equivalent of a few thousand dollars by today’s standard.

If government regulation wouldn’t improve working conditions, competition might. In 1891, Salvation Army founder William Booth joined the fight against the use of white phosphorous. He opened a factory that refused to use the chemical in the hopes that it would pressure other factories to do the same.

His factory gave consumers a way to boycott the white phosphorus matches while also offering them job security.

The Salvation Army matches carried a label that promised they were: “manufactured under Healthy Conditions,” and were: “Entirely free from the Phosphorus which causes ‘Matchmaker’s Leprosy.'”

Despite their moral superiority, however, the Salvation Army matches didn’t sell well, and it wasn’t until French chemists discovered sesquisulfide, a safe substitute for white phosphorus, that finally brought an end to the practice. Bryant & May switched to the alternative in 1901.

Britain finally banned white phosphorus altogether in 1910, but by then decades had passed since a doctor in Vienna first determined that it caused phossy jaw in matchstick girls. By then, it was too late to undo the damage it had wrought to so many laborers in the name of better matches.

After learning about the horrors of phossy jaw in 19th-century matchstick girls, learn about the radium girls, women who were told to lick radioactive paint at work — and suffered for it. Then, check out other awful jobs from history.