Before the existence of the Secret Service and the FBI, the Pinkerton Detective Agency was America’s premier security and intelligence organization — until its reputation for violence and strikebreaking caused it to lose favor with the public.

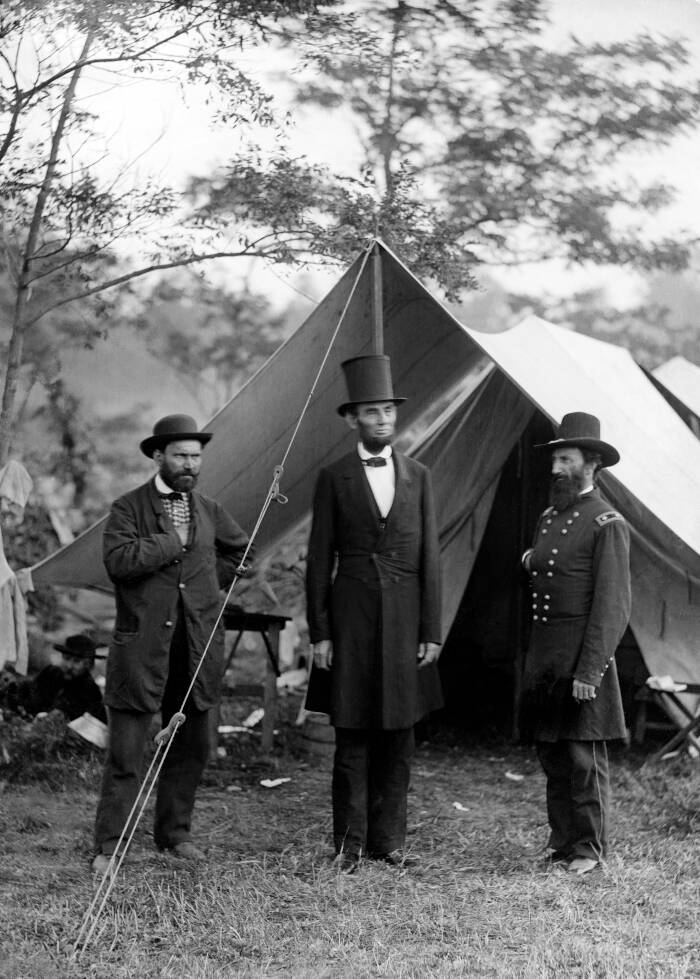

Wikimedia CommonsAllan Pinkerton (left) with Abraham Lincoln and General John A. McClernand at Antietam, 1862.

When Allan Pinkerton first set foot on American soil in 1842, he was a humble cooper who’d survived poverty and political turmoil in his native Scotland. But within 40 years, he would build an elite private detective force renowned nationwide for preventing train robberies, hunting down Wild West convicts, and breaking strikes.

A security and intelligence company, the Pinkerton Detective Agency remains widely known to this day as the first private detective organization in American history. In fact, Pinkerton’s logo — an illustration of an eye above the motto “We never sleep” — inspired the creation of the term “private eye” to describe a hired detective.

The Pinkertons filled the roles of the Secret Service and FBI before such organizations existed, and at one point even acted as security for President Abraham Lincoln. However, the agents’ reputation for violence eventually caused the organization to fall out of public favor.

This is the story of the rise and fall of the Pinkerton Detective Agency.

Allan Pinkerton’s Early Detective Work

Allan Pinkerton didn’t start out as a detective. Born in Scotland in 1819, he grew up to become a cooper and soon became an active member of his country’s pro-labor Chartist movement. Eventually, British authorities began to crack down on the Chartists, and Pinkerton fled Scotland, moving to Illinois in 1842.

Pinkerton settled with his wife Joan in the small settlement of Dundee, where he opened a cooperage. Then, one day in 1847, while searching an island in the Fox River for wood to use in barrel staves, Pinkerton happened upon a group of counterfeiters. When he realized that they were making fake coins, he alerted the sheriff and accompanied him to make the arrest.

This feat made Pinkerton a local hero. Soon, businesses began calling on him to investigate other counterfeiters.

“I suddenly found myself called upon, from every quarter, to undertake matters requiring the detective skill,” Pinkerton later wrote, according to S. Paul O’Hara’s book Inventing the Pinkertons. He gave up his cooperage, becoming a sheriff’s deputy in Kane and Cook Counties and then a special agent for the U.S. Postal Service.

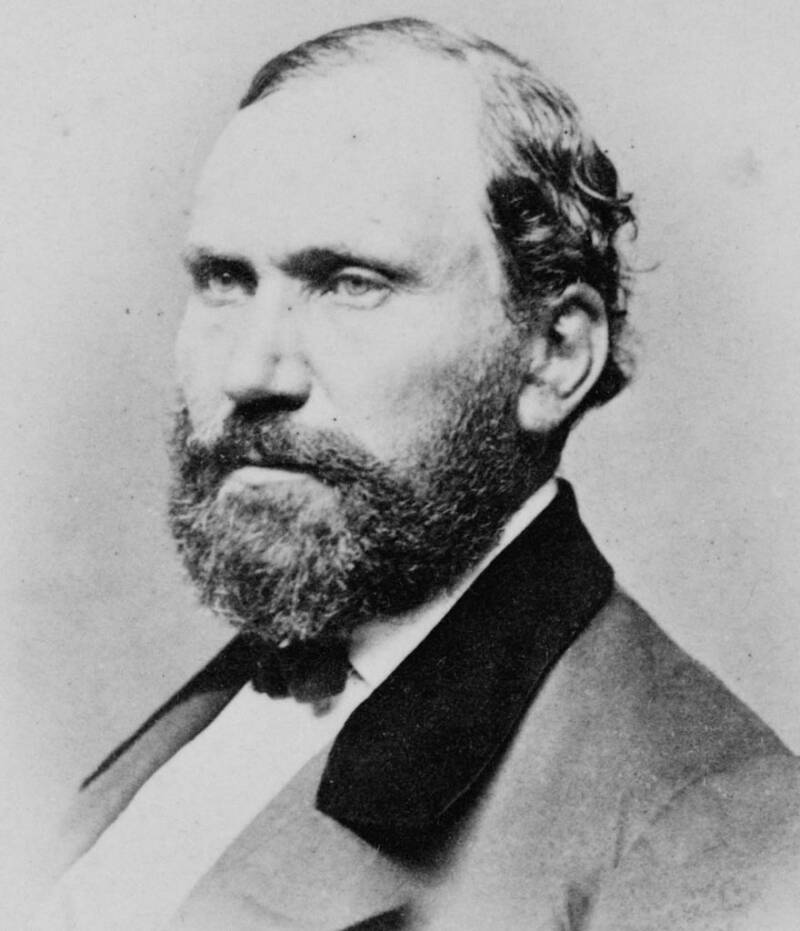

Wikimedia CommonsAllan Pinkerton, founder of the Pinkerton Detective Agency.

Pinkerton built his reputation as a lone detective. But in 1855, six railroads hired him for protection against the growing threat of train robberies. To meet this sudden influx in demand for his services, he formed the North-Western Police Agency — a security and detective company that would later become the Pinkerton National Detective Agency.

Building A Detecting Empire

Within a few years, Allan Pinkerton had built his agency into the country’s premier detective organization. In the 1850s, Pinkerton employed 15 agents. One of these was Kate Warne, the first female detective in the United States. Warne was so effective that Pinkerton would later ask her to lead an all-female division within the company.

Headquartered in Chicago, the group initially operated as a security force hired by train companies to prevent robberies, often tracking down massive stashes of embezzled money for major organizations like the Adams Express Company.

But by 1860, tension was brewing between the North and the South. And with it came opportunities that would truly put Pinkerton on the map.

The Pinkertons In The Civil War

Allan Pinkerton had made a number of valuable contacts during his time working for railroads. One of these was George B. McClellan, a Mexican-American War veteran and the former chief engineer of the Illinois Central Railroad. When McClellan was appointed commander of Union forces, he asked Pinkerton to form an intelligence service.

Before the fighting even began, Pinkerton claimed to have discovered a plot to assassinate Abraham Lincoln in Baltimore. He convinced the president-elect to change his itinerary as he traveled to Washington, possibly saving his life.

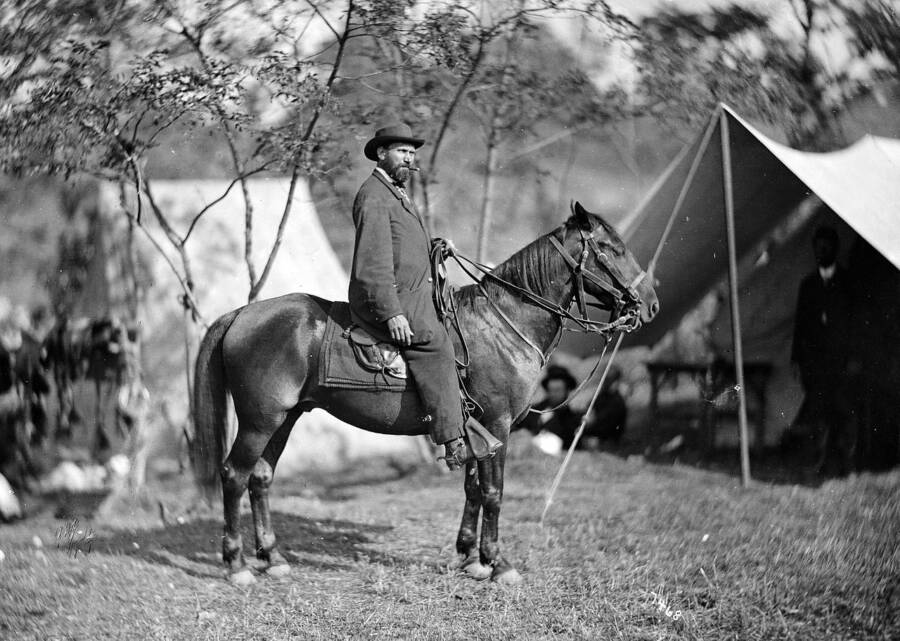

Wikimedia CommonsAllan Pinkerton at Antietam, 1862.

After foiling this alleged “Baltimore plot,” the Pinkertons served as Lincoln’s private security during the war. They were also enlisted to infiltrate the South and steal Confederate secrets. Pinkerton himself began traveling behind enemy lines, disguised as Confederate Major “E.J. Allen.”

Unfortunately, much of the intelligence collected by Pinkerton agents was false, and ended up hindering the Union more than it helped. Many of the Confederate soldiers and civilians they interviewed misled them about the strength and size of Confederate armies, often leading McClellan to believe he was facing much larger forces than he was.

Eventually, after a crushing defeat at Antietam, Lincoln finally lost patience and dismissed McClellan. Pinkerton went with him.

The Golden Age Of The Pinkertons

The 1870s and 1880s were the heyday of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. After the war, the group opened new offices in Philadelphia and New York to meet rising demand.

As the Pinkertons gained renown, the agency was enlisted to track down infamous Wild West outlaws like the Reno Gang, Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch, and Jesse and Frank James. The Pinkertons also hired famous Old West figures like Charlie Siringo and Tom Horn.

Around this time, Pinkerton amassed the world’s largest collection of mugshots and also built a first-of-its-kind criminal database. Meanwhile, Allan Pinkerton made the company famous by writing a series of hit true crime novels based on his agents’ daring exploits.

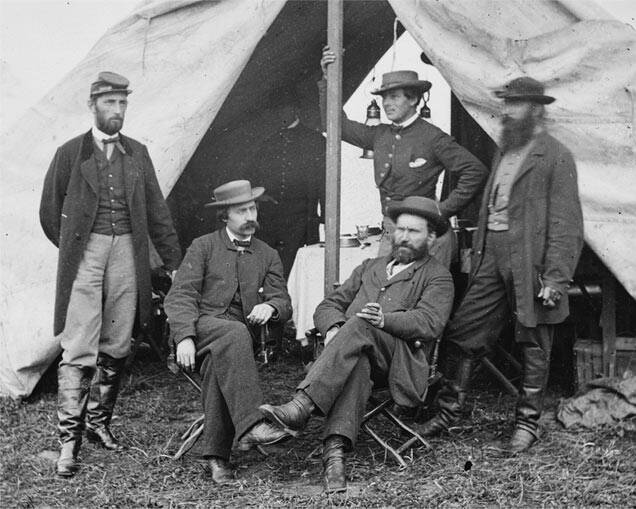

Wikimedia CommonsThe Pinkertons are considered America’s first private detective organization.

But “the Pinks” also developed a reputation for exceptional brutality. Agents often used any means necessary to catch their targets, sometimes killing innocent civilians in the process.

While hunting down the James brothers in 1875, they set the brothers’ house on fire, inadvertently triggering a series of explosions that injured the brothers’ mother and killed their eight year-old half brother, Archie. Allan Pinkerton’s son William would later admit that the hunt for the James gang had become a “war of extinction” after a Pinkerton agent was killed while pursuing the brothers.

As the Pinkerton Detective Agency gained fame for their exploits in the West, they also began to play a significant role in policing the booming industrial settlements cropping up throughout the United States. In fact, it was in coalfields, factories, and rail yards that the Pinkerton Agency made its lasting mark — and where their downfall began.

A Legacy Of Violence

After the Civil War, workers in many booming post-war industries began to strike for better conditions and pay. And by the 1870s, with decades of experience and hundreds of agents to their name, the Pinkertons were a natural choice when it came to strikebreaking.

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, American companies frequently hired the Pinkerton Detective Agency to quash strikes. Agents would infiltrate unions and serve as spies for company bosses. Then, they’d crack down on the striking workers — sometimes using brutal violence.

Public domainPinkerton adopted the motto “we never sleep” and a logo bearing an illustration of an eye — giving rise to the term “private eye” to describe a hired detective.

In 1877, the Pinkertons were hired to bust the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, which involved over 100,000 workers. The resulting conflict left about 100 dead.

Around the same time, Pinkerton detective James McParland was assigned to infiltrate the Molly Maguires. This secret society of Irish immigrant coal miners allegedly resorted to violent tactics in their fight for better pay and safer working conditions. McParland spent much of 1876 living among the Molly Maguires, gaining their trust and eventually gathering enough evidence to send 10 of their leaders to the gallows.

After a Pinkerton agent killed a 15-year-old bystander during an 1887 dockworkers’ strike in Jersey City, New Jersey, the United Labor Party declared that “Pinkerton men go from state to state committing murders for which none of them are ever brought to trial.”

As more of these stories broke, the public became increasingly alarmed by the Pinkertons’ violent tactics.

“Rumors persisted that detectives secretly worked on both sides of the same case, kidnapped witnesses, bribed juries, [and] commonly used violence to break strikes and coerce confessions,” Frank Richard Prassel wrote in his book The Western Peace Officer: A Legacy of Law and Order, according to the American Heritage Center.

The End Of The Pinkerton Era

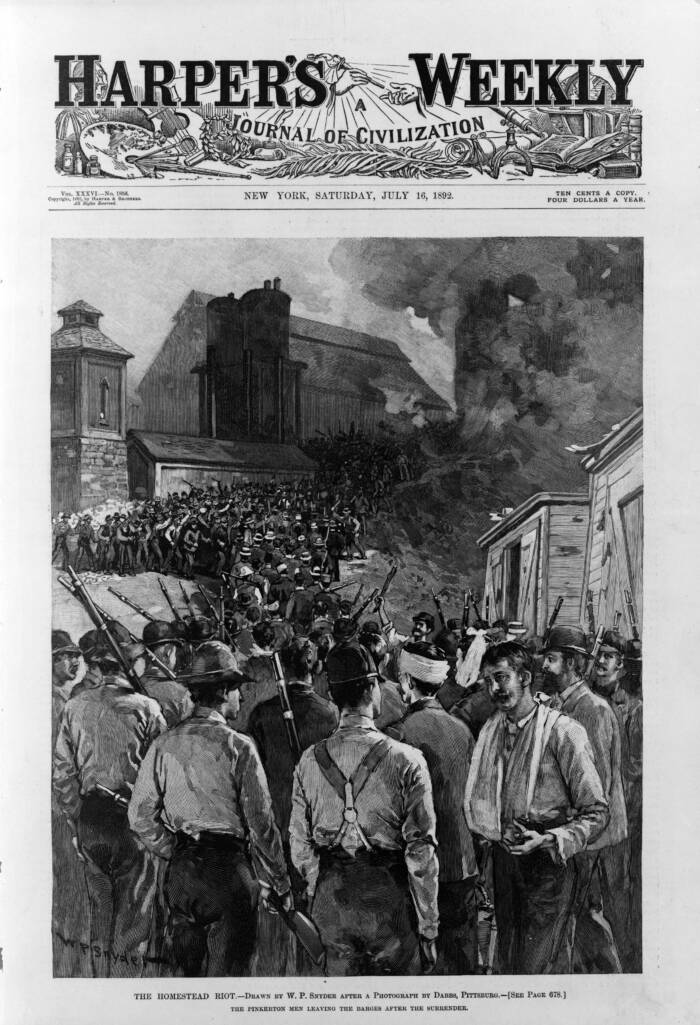

Wikimedia CommonsDuring the Homestead strike, about a dozen people lost their lives, and the Pinkerton Detective Agency lost significant public sympathy.

The most notorious event in the Pinkerton Agency’s labor history came in 1892. That year, 3,800 workers at the Carnegie Steel plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania went on strike over wage cuts. In response, Andrew Carnegie’s chief lieutenant, Henry Clay Frick, promptly fired all of them and brought in 300 Pinkerton agents to occupy the plant.

But before the agents could get there, on July 6, thousands of striking workers armed themselves and fortified the Homestead site, gathering along the Monongahela River to fight off the Pinkerton agents. The ensuing 12-hour clash left about a dozen people dead.

The use of a private army to break a strike, and the violence with which they acted, all but obliterated sympathy for the Pinkertons. In 1893, Congress passed the Anti-Pinkerton Act, making it illegal for the federal government to hire private security forces or mercenaries.

Following the passage of this new law, the Pinkerton National Detective Agency could continue to work with private companies. However, the rise of the FBI and modernized police forces eventually rendered their services obsolete, finally bringing an end to the Pinkerton era.

But that wasn’t the end of the agency itself.

Even as the union-busting and investigative work they’d depended on for almost a century dried up, Pinkerton turned to private security work, and they were eventually bought by Swedish security company Securitas AB. The agency exists as a Securitas subsidiary to this day.

After learning about the troubling history of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, take a look at the story of the Molly Maguires, the workers’ movement they destroyed. Then, learn about the secret societies that some believe run the world.