Venice's Poveglia Island was a quarantine center and mass grave for victims of bubonic plague, earning it the nickname the "Island of Ghosts."

In the Venetian lagoon sits Poveglia Island, a small, unpopulated landmass cut down the middle by a canal. For all its unassuming appearance, however, it has a dark history and is said to be one of the most haunted places in Europe, a continent saturated with tales of ghosts and the paranormal.

Many of those ghosts came courtesy of the Black Death, which swept through Europe in the 14th century, killing off millions of people and cutting the entire population of some cities in half in a matter of months or even weeks. And the bubonic plague didn’t stop after the famous outbreak of 1348. Instead, it reappeared again and again for centuries.

Luigi Tiriticco/FlickrA photograph showing the only standing buildings on Poveglia Island.

In Venice — Europe’s dominant trading port during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance — officials took advantage of the Venetian lagoon’s islands to isolate and manage its plague outbreaks. For centuries, Poveglia Island was Venice’s solution to the plague: An isolated quarantine site where victims of the plague were sent after infection with few ever leaving the island again.

The small island, just 17 acres, housed over 160,000 plague victims through the centuries and officials did more than just quarantine the sick and soon to die. They burned the corpses to stop the spread of the disease and it is said that human ash from these cremations make up more than 50 percent of the island’s soil, even centuries later. It sounds like Hell, just in Northern Italy.

The History Of Poveglia Island

The picturesque Venetian Lagoon houses 166 islands, including a small island directly south of the Piazza San Marco. Known as Poveglia Island, the small dot of land has housed people since at least the fifth century when Romans escaped Goth and Hun invasions by fleeing to more defensible islands in the lagoon.

Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg/Universitätsbibliothek HeidelbergA 1572 map of Venice showing the many islands of the lagoon.

As Venice grew into a major power, Poveglia became an important defensive location. In the 14th century, the Venetians built a fort on the island, establishing an outpost that could destroy enemy ships that tried to reach the city of Venice.

But when bubonic plague ravaged Europe, Poveglia Island became the quickest and eventually permanent solution to the outbreak: it became an important quarantine site for plague victims as early as the 16th century.

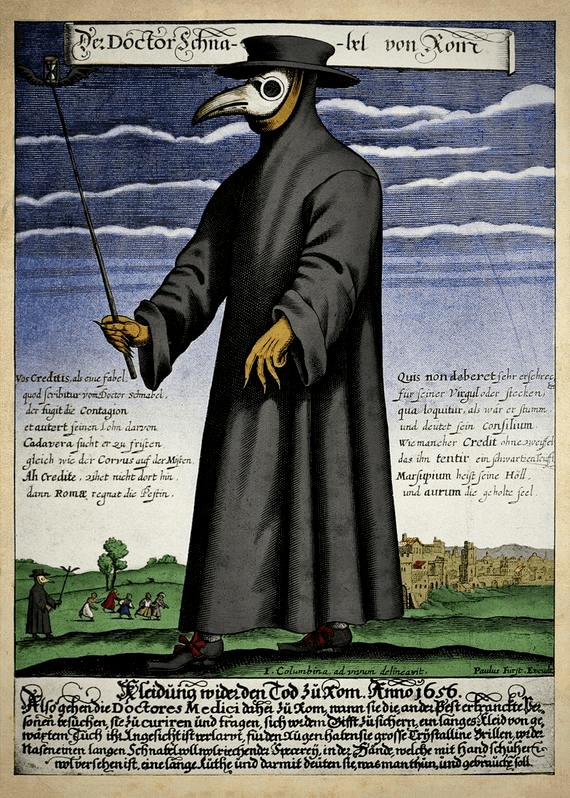

Paul Fürst/Wikimedia CommonsA 17th century plague doctor.

In addition to quarantining plague victims on Poveglia, the island also became a gigantic mass grave for the corpses of the dead. Barges from Venice hauled the dead to the island, while smaller ships brought exiles from the city who showed even the mildest symptoms of plague.

On Poveglia Island, plague victims spent forty days waiting to see if they would die or recover. Most died. The Venetians cremated untold thousands of bodies on Poveglia, leaving the ashy remains of plague victims to fall where they may.

Containing The Plague Through Quarantines

When the deadliest outbreak of bubonic plague, Black Death, struck Europe in 1348, Venice created the first modern quarantine system. The republic detained ships and travelers suspected of carrying the plague for a period of forty days — the word quarantine itself comes from the Italian quaranta, or forty.

Although plague quarantines were largely ineffective, the desperate need to stop the spread of disease drove other areas to adopt the practice. During a reappearance of the bubonic plague in 1374, the Duke of Milan exiled all plague sufferers to a field outside the city. On the Dalmatian coast, Ragusa created a quarantine station to isolate people from plague-ravaged areas.

Marseilles created a maritime quarantine in the early 16th century, while 17th-century Frankfurt banned anyone living in a plague-afflicted house from attending public gatherings. In colonial New York, the city council set up a quarantine station on the island that now houses the Statue of Liberty.

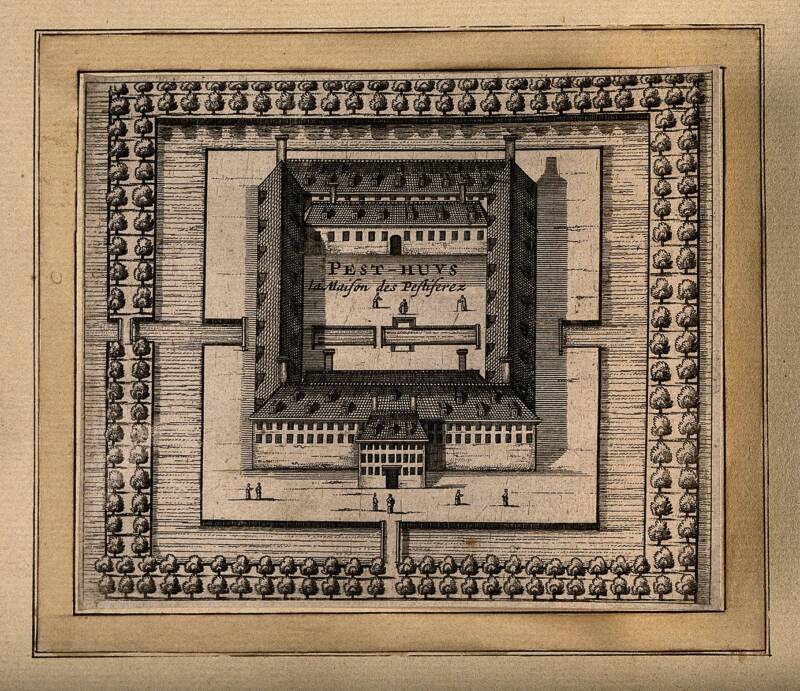

Unknown/Wellcome ImagesA plague house to quarantine victims in Leiden.

Venice’s Lazaretti System Of Plague Quarantine Stations

The Black Death devastated Venice’s population in 1348, killing half of its citizens. As Venice was a hub for international trade, it welcomed ships from around the known world, making the island republic especially susceptible to the spread of disease.

As bubonic plague ravaged Europe for centuries, Venice responded by creating a network of lazaretti, or plague quarantine stations, on the islands of the lagoon. Poveglia Island became the most important of these inspection ports by the 18th century.

In 1485, Venice’s ruler, Giovanni Mocenigo, died from another outbreak of the plague which spurred the city to create several quarantine colonies on isolated islands. “When plague struck the town, everybody sick or showing any suspect symptoms were restricted on the island until they recovered or died,” explains anthropologist Luisa Gambaro.

On Lazzaretto Vecchio, an island northeast of Poveglia Island, the number of corpses soon overwhelmed the city’s capacity to bury them. Archaeologist Vincenzo Gobbo said: “About 500 people a day used to die in Lazzaretto Vecchio. [Corpse carriers] simply had no time to take care of the burials.”

Angelo Meneghini/Wikimedia CommonsVines grow over the buildings still standing on Poveglia Island.

“It looked like hell,” wrote 16th-century chronicler Rocco Benedetti. “The sick lay three or four in a bed.”

When plague victims died, they were thrown into mass graves. “Workers collected the dead and threw them in the graves all day without a break,” Benedetti recorded. “Often the dying ones and the ones too sick to move or talk were taken for dead and thrown on the piled corpses.”

From the 16th century on, Poveglia Island housed plague victims and there many breathed their last and were cremated or buried in mass graves. But the island became even more important in Venice’s epidemic prevention plans in the 18th century.

In 1777, Venice’s Magistrate of Health turned Poveglia Island into its primary plague checkpoint. Any ship sailing to Venice had to stop at Poveglia first for an inspection. If any sailor showed signs of plague, Venice quarantined them on Poveglia Island.

Giacomo Guardi/Metropolitan Museum of ArtBritish ships undergoing inspection on Poveglia Island, c. 1800.

Poveglia Island Mental Hospital

Poveglia Island remained an important plague quarantine site until 1814 and owing to its haunting legacy as the city’s go-to quarantine station for the plague, Venetians began calling Poveglia Island the “Island of Ghosts.”

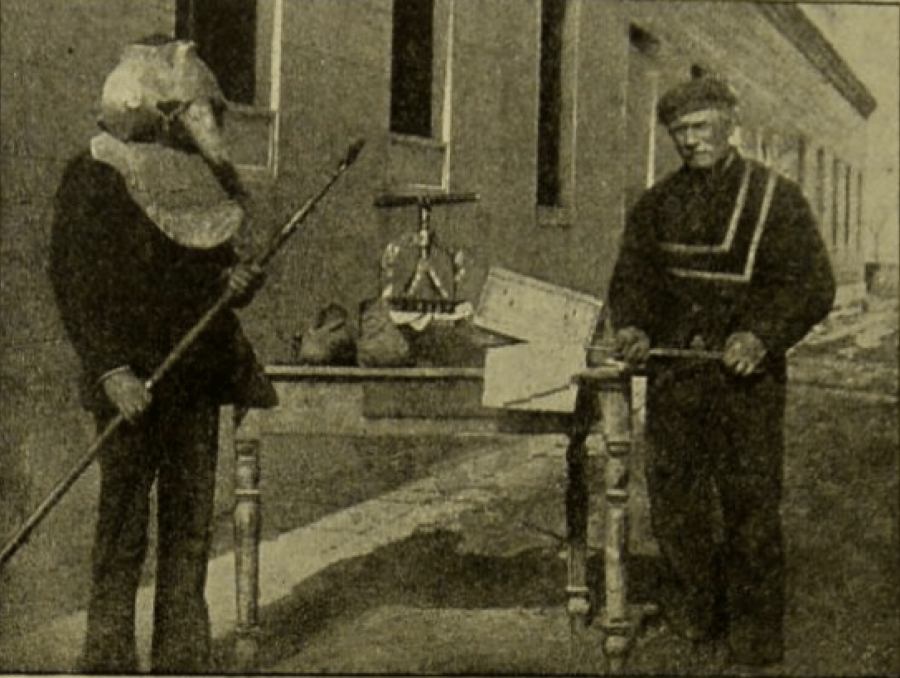

Theodor Weyl/Wikimedia CommonsLate-19th century visitors to Poveglia Island found plague equipment.

Adding to the Poveglia’s dark history, in 1922, Venetians transformed the island by building a mental hospital there. Naturally, rumors soon spread that a doctor at the hospital carried out morbid experiments on his patients, only to reportedly died after falling from a bell tower on the island.

The hospital closed its doors in 1968, leaving Poveglia Island once again abandoned. Not surprisingly, stories of plague victims and now abused psychiatric patients haunting Poveglia Island continue to this today.

In 2014, Venice unsuccessfully tried to auction off the island but the deal fell through and the island’s status remains in limbo. Today, the “Island of Ghosts” is completely off-limits to visitors. Why anyone would want to visit such a place is anyone’s guess.

Now that you’ve read the story of Poveglia Island in the Venetian lagoon, learn more about plague doctors and their unusual costume for combatting the notorious disease. Then read about the most haunted places on Earth.